Strength Training & Metabolic Flexibility: New 2026 Insights on Muscle Fuel Utilization

Learn how strength training rewires your metabolism—boosting metabolic flexibility and preventing harmful intramuscular fat buildup

EXERCISEMETABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D. {Internal Medicine}.

1/8/202614 min read

Metabolic flexibility—the body’s ability to shift smoothly between burning carbohydrates and fats—is emerging as one of the most important predictors of endurance, energy stability, and long-term metabolic health. Traditionally, endurance athletes have relied on long runs, cycling, and steady aerobic training to build this adaptability. But a surprising reality has become clear: strength training can enhance metabolic flexibility just as powerfully by reshaping muscle at the cellular and mitochondrial levels.

When you perform compound lifts such as squats, deadlifts, or farmers walks, your muscles activate powerful energy-sensing pathways that teach the body to use fuel more efficiently. At the same time, resistance training stimulates the production of new, healthier mitochondria—your cells’ energy factories—allowing you to burn more fat, delay fatigue, and maintain better metabolic control during both low-intensity and high-intensity work.

For patients, this means steadier blood sugar, improved fat oxidation, and greater protection against intramuscular fat accumulation. For athletes, it translates into better running economy, higher lactate thresholds, faster recovery between intervals, and the ability to sustain performance without energy crashes. Strength training is no longer just about lifting heavier weights—it is about building a more adaptable

Clinical pearls .

1. Muscle is a "Metabolic Sink"

Think of your muscles not just as tools for movement, but as a sponge for blood sugar. Science shows that muscle is the primary site for glucose disposal. By increasing your muscle mass—even slightly—you provide your body with a larger "sink" to drain excess sugar from your bloodstream, significantly lowering your risk of metabolic issues like Type 2 Diabetes.

2. The "Running Economy" Advantage

Strength training for runners isn't about getting "bulky"; it's about musculotendinous stiffness. When your tendons and muscles are strong, they act like high-quality springs. Every time your foot hits the ground, they store and release energy more efficiently. This "free" energy reduces the amount of oxygen your heart needs to pump, effectively making you faster at the same effort level.

3. "Quiet" Inflammation from Internal Fat

Not all fat is the same. Intramuscular adipose tissue (IMAT)—fat that hides inside your muscle fibers—is particularly stubborn. Unlike the fat under your skin, IMAT releases inflammatory signals directly into your muscle cells, which can slow down recovery after a workout or injury. Regular resistance training is the most effective "detergent" to keep your muscle tissue clean and functional.

4. Absolute vs. Relative Endurance

A common misconception is that lifting heavy weights ruins stamina. In reality, increasing your absolute strength (the maximum weight you can lift) makes every sub-maximal movement (like a pedal stroke or a stride) feel easier. If your legs are 20% stronger, pushing a bike pedal requires a smaller percentage of your total capacity, allowing you to go longer before hitting the "wall."

5. The Interference Effect is a Myth (Mostly)

Many athletes worry that lifting weights will "cancel out" their cardio gains. Recent umbrella reviews confirm that for 95% of people, concurrent training (doing both) is actually synergistic. As long as you allow a 3-to-6-hour window between a hard lift and a hard run, your body is perfectly capable of adapting to both, resulting in a more resilient, "all-weather" physiology.

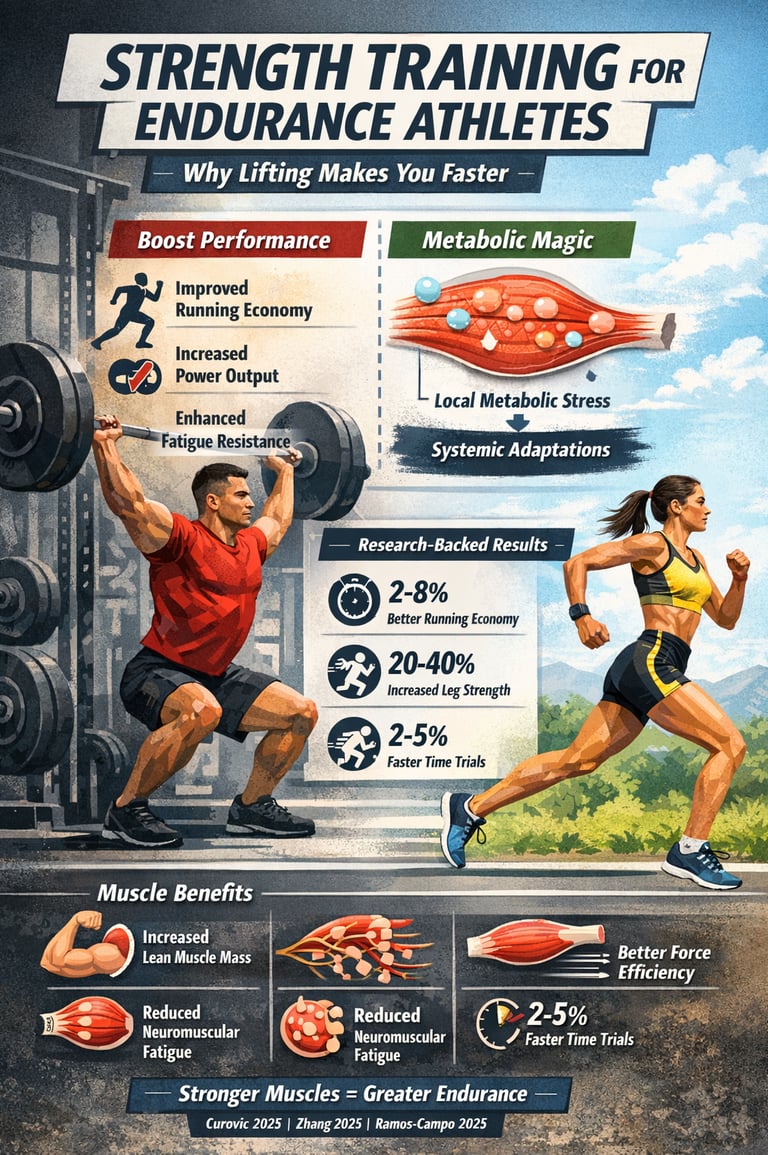

The Metabolic Magic: How Condensed Training Volume Could Be Your Secret Weapon

Here's something that might surprise you: the way you structure your resistance training volume could matter more than you think. A groundbreaking perspective published in Frontiers in Physiology by Curovic (2025) challenges conventional wisdom about workout programming.

Understanding Local Metabolic Stress

When you perform resistance exercise, your muscles experience what scientists call local metabolic stress—essentially, a buildup of metabolites like lactate, hydrogen ions, and inorganic phosphate within the muscle tissue. But here's where it gets interesting: Curovic (2025) proposes that condensing your training volume into more concentrated sessions might amplify these metabolic signals in ways that spread benefits throughout your entire body.

Think of it like this: instead of spreading 15 sets across the week in three moderate sessions, what if you performed those same sets in a more concentrated format? The research suggests this approach could trigger stronger systemic adaptations—improvements that go far beyond the specific muscles you're training.

Key takeaways from this study:

Metabolic stress from resistance training creates signals that affect your whole body, not just trained muscles

Condensed training volumes might enhance hormonal responses, cardiovascular adaptations, and metabolic health

This approach could offer greater benefits while actually saving time—perfect for busy endurance athletes

The anabolic signaling pathways activated by concentrated metabolic stress may improve both muscle growth and functional capacity

The implications? You might not need to spend hours in the gym every week. Strategic, high-intensity resistance training sessions could deliver superior results for your functional fitness and athletic performance (Curovic, 2025).

The Endurance Paradox: Why More Muscle Means Better Performance

Let's address the elephant in the room: many endurance athletes fear that building muscle will slow them down. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (2025) in Sports Medicine puts this myth to rest definitively.

Muscle Mass and Endurance: The Surprising Connection

After analyzing multiple studies involving cyclists, runners, and other endurance athletes, Zhang and colleagues (2025) discovered something remarkable: greater muscle mass is actually associated with improved endurance performance and reduced neuromuscular fatigue.

Here's what the data shows:

Athletes with higher lean body mass demonstrated better performance in prolonged endurance activities

Increased muscle mass helps delay the onset of peripheral fatigue during long-duration exercise

Muscle architecture changes from resistance training improve force production efficiency

The relationship between muscle mass and endurance follows a sweet spot—you don't need bodybuilder-level hypertrophy to benefit

Key takeaways from Zhang et al. (2025):

Moderate increases in muscle cross-sectional area enhance endurance capacity without hindering aerobic performance

Neuromuscular fatigue resistance improves with greater muscle mass, allowing you to maintain form longer

The quality of muscle tissue (not just quantity) matters for endurance exercise performance

Resistance training-induced muscle adaptations can protect against the catabolic effects of high-volume endurance training

This research fundamentally changes how we should think about body composition for endurance sports. That extra muscle isn't dead weight—it's your fatigue-fighting secret weapon (Zhang et al., 2025).

Muscular Endurance: The Missing Link in Your Training Program

Now, let's talk about a concept that bridges pure strength and pure endurance: muscular endurance. A comprehensive review by Hammert et al. (2025) in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research examines how resistance training affects your muscles' ability to perform repeated contractions over time.

Absolute vs. Relative Muscular Endurance

The researchers make a crucial distinction that every athlete should understand:

Absolute muscular endurance refers to how many repetitions you can perform at a fixed weight. After strength training, this typically improves because your muscles become stronger and more resistant to fatigue.

Relative muscular endurance means how many reps you can do at a percentage of your maximum strength (like 60% of your one-rep max). Interestingly, this doesn't always improve with training, and sometimes it can even decrease slightly.

Why does this matter? Because in endurance sports, you're typically working against your body weight or a fixed external resistance (like wind resistance while cycling). Improvements in absolute strength translate directly to better performance in these scenarios.

Key takeaways from Hammert et al. (2025):

Resistance training protocols consistently improve absolute muscular endurance across different muscle groups

Even traditional hypertrophy training (8-12 reps) enhances endurance capabilities

The improvements occur through multiple mechanisms: increased muscle fiber size, better oxidative capacity, and enhanced buffering capacity

Practical application: your stronger legs won't just help you sprint—they'll help you maintain pace during the final miles of a marathon

The researchers emphasize that training adaptations from resistance work complement rather than compete with aerobic training. Your muscles develop a more robust foundation for handling sustained work (Hammert et al., 2025).

The Umbrella View: What Comprehensive Research Tells Us About Concurrent Training

When you want the big picture, you look at an umbrella review—essentially, a review of reviews. Ramos-Campo et al. (2025) conducted exactly this type of comprehensive analysis, examining multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses on how strength training affects endurance performance determinants in middle and long-distance athletes.

The Performance Boosters You Can Measure

This massive analysis, published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, reveals that resistance training significantly improves several key performance markers:

Running Economy: Perhaps the most important finding—strength training improves running economy (the oxygen cost of running at a given speed) by 2-8%. For context, that's roughly equivalent to months of additional aerobic training. The mechanism involves improved musculotendinous stiffness, better force production, and more efficient ground contact mechanics.

Lactate Threshold: Your ability to sustain higher intensities before lactate accumulation improves with concurrent training. This means you can push harder before hitting that wall of fatigue.

Maximal Strength: Obviously strength improves, but the magnitude matters—increases of 20-40% in lower body strength are common, which directly translates to better power output during endurance activities.

Time Trial Performance: The bottom line—actual race times improve. Studies show 2-5% improvements in time trial performance when endurance athletes add resistance training to their programs.

Key takeaways from Ramos-Campo et al. (2025):

Plyometric training and heavy resistance training (>85% 1RM) produce the most consistent benefits for endurance athletes

Training frequency of 2-3 sessions per week appears optimal for concurrent training benefits

The interference effect (resistance training hindering endurance gains) is minimal when programming is appropriate

Periodization matters—integrating strength work strategically throughout your training cycle maximizes benefits

The evidence is overwhelming: resistance training isn't supplementary for endurance athletes—it's essential for reaching your full potential (Ramos-Campo et al., 2025).

The Hidden Enemy: How Intramuscular Fat Sabotages Recovery

Research by Norris et al. (2025) in Cell Reports reveals that intramuscular adipose tissue (IMAT)—fat deposited between muscle fibers—significantly restricts functional muscle recovery after injury or periods of disuse.

Why This Matters for Active Individuals

Even if you're injury-free, understanding IMAT is crucial. This isn't the subcutaneous fat you can pinch—it's fat that infiltrates muscle tissue, and it's more common than you might think, especially with aging, sedentary behavior, or poor metabolic health.

The research team discovered that IMAT creates a hostile environment that prevents proper muscle regeneration. It does this through several mechanisms:

Producing inflammatory signals that interfere with muscle satellite cells

Creating physical barriers that prevent new muscle fibers from forming properly

Disrupting the normal metabolic signaling needed for recovery

Contributing to insulin resistance within muscle tissue

Key takeaways from Norris et al. (2025):

Intramuscular fat accumulation is not just a cosmetic issue—it's a functional problem

Regular resistance exercise helps prevent IMAT accumulation by maintaining muscle mass and metabolic health

Recovery from injury or training periods becomes progressively harder as IMAT increases

Combining endurance training with strength training offers the best protection against IMAT development

This research underscores why maintaining muscle quality through regular resistance training is crucial for long-term athletic performance and injury recovery (Norris et al., 2025).

The Metabolic Masterclass: Exercise as Medicine for Type 2 Diabetes

While not exclusively focused on athletes, the narrative review by Zhao et al. (2025) in Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications provides crucial insights into how different exercise modalities affect metabolic health—information that's valuable for anyone concerned with body composition and performance.

The researchers detail how both endurance exercise and resistance exercise combat type 2 diabetes mellitus through distinct but complementary pathways:

Endurance exercise mechanisms:

Increases insulin sensitivity through enhanced GLUT4 translocation

Improves mitochondrial function and oxidative capacity

Reduces systemic inflammation

Enhances cardiovascular health and blood flow

Resistance exercise mechanisms:

Increases muscle mass, which serves as the primary site for glucose disposal

Elevates resting metabolic rate through greater lean tissue maintenance

Improves glycemic control through different cellular signaling pathways than aerobic exercise

Enhances protein synthesis and nutrient partitioning

Key takeaways from Zhao et al. (2025):

Concurrent training (combining both modalities) produces superior metabolic adaptations compared to either alone

Resistance training may be particularly important for glucose management through increased muscle mass

The molecular mechanisms involve activation of AMPK, mTOR, and PGC-1α pathways—the same pathways that improve athletic performance

Regular exercise creates a metabolic environment that enhances nutrient utilization and energy efficiency

For athletes, this research reinforces that the metabolic benefits of strength training extend far beyond muscle growth. You're literally rebuilding your body's metabolic machinery (Zhao et al., 2025).

Practical Application: Building Your Optimal Training Program

So how do you actually implement this research? Here's a science-based framework for integrating resistance training with your endurance training:

Weekly Training Structure

For Endurance Athletes (Marathon, Cycling, Triathlon):

3-4 endurance sessions focusing on your primary sport

2-3 resistance training sessions emphasizing heavy loads (85%+ 1RM) or plyometric exercises

At least one day of complete rest for recovery and adaptation

Session Timing:

Perform high-intensity endurance and strength training on the same day when possible (to maximize recovery days)

Allow 3-6 hours between sessions if training twice daily

Schedule heavy resistance training after easier aerobic sessions, not before hard interval workouts

Exercise Selection for Endurance Athletes

Lower Body Priorities:

Squats (back, front, or goblet variations) for overall leg strength

Deadlifts or Romanian deadlifts for posterior chain development

Single-leg exercises (split squats, step-ups) for functional strength and balance

Calf raises for ankle strength and injury prevention

Plyometric drills (box jumps, bounds) for power and reactive strength

Upper Body and Core:

Pulling movements (rows, pull-ups) for postural strength

Pushing movements (push-ups, bench press) for balance

Anti-rotation core exercises for stability

Planks and carries for endurance-specific core strength

Progressive Overload Strategy

The concept is simple but crucial: gradually increase the demands on your muscles to force continued adaptation. For endurance athletes new to strength training:

Weeks 1-4: Focus on technique with moderate loads (60-70% 1RM), 2-3 sets of 8-12 reps Weeks 5-8: Increase load (75-85% 1RM), maintain good form, 3-4 sets of 6-10 reps Weeks 9-12: Incorporate heavy resistance training (85-90% 1RM), 4-5 sets of 4-8 reps Ongoing: Cycle between these phases based on your competitive season and training goals

Nutrition Considerations

Protein Timing: Consume 20-40g of protein within 2 hours post-resistance training to support muscle protein synthesis

Carbohydrate Strategy: Don't neglect carbs on strength training days—your muscles need glycogen for both endurance and resistance work

Overall Intake: Endurance athletes doing concurrent training need slightly more calories (200-400 extra daily) to support both aerobic adaptations and muscle growth

Common Concerns Addressed

"Won't extra muscle slow me down?"

The research is clear: moderate muscle hypertrophy from resistance training improves rather than impairs endurance performance. The key is appropriate programming—you're not trying to become a bodybuilder, you're optimizing your power-to-weight ratio and fatigue resistance (Zhang et al., 2025).

"I don't have time for both types of training."

The condensed volume approach from Curovic (2025) suggests you might need less time than you think. Two focused 30-45 minute resistance training sessions weekly can produce significant benefits. Additionally, the improved running economy and reduced injury risk may actually reduce the volume of endurance training needed.

"Will strength training interfere with my endurance adaptations?"

When programmed correctly, the interference effect is minimal. The umbrella review by Ramos-Campo et al. (2025) shows that concurrent training produces complementary adaptations. The key is proper spacing between high-intensity sessions and adequate recovery nutrition.

The Recovery Revolution: Why Rest Days Matter More Than You Think

One theme that emerges across all this research is the critical importance of recovery. The adaptations we're seeking—improved muscle mass, enhanced metabolic efficiency, better neuromuscular function—all occur during rest, not during training.

Recovery strategies supported by research:

Sleep 7-9 hours nightly for optimal hormonal balance and tissue repair

Active recovery (light movement) on rest days to enhance blood flow without adding stress

Adequate protein intake (1.6-2.2g per kg body weight daily) for muscle recovery

Stress management techniques to prevent excessive cortisol from hindering adaptations

Periodized training with planned deload weeks every 3-4 weeks

The research on IMAT by Norris et al. (2025) reminds us that proper recovery isn't just about avoiding overtraining—it's about creating the optimal environment for your muscles to rebuild stronger and healthier.

Key Takeaways: Your Action Plan

Let's distill this extensive research into actionable wisdom:

Resistance training is non-negotiable for endurance athletes who want to reach their full potential. The evidence for improved running economy, lactate threshold, and overall performance is overwhelming (Ramos-Campo et al., 2025).

Muscle mass matters for endurance performance. Moderate increases in lean tissue improve fatigue resistance and neuromuscular function without compromising aerobic capacity (Zhang et al., 2025).

Training structure matters as much as volume. Consider condensed training sessions that create greater metabolic stress for potentially superior systemic adaptations (Curovic, 2025).

Both absolute and relative muscular endurance improve with resistance training, translating to better sustained performance in your primary sport (Hammert et al., 2025).

Metabolic health underpins performance. Regular strength training improves insulin sensitivity, prevents intramuscular fat accumulation, and enhances overall metabolic function (Zhao et al., 2025; Norris et al., 2025).

Quality over quantity in muscle tissue. Preventing IMAT through regular resistance exercise protects your recovery capacity and long-term performance potential (Norris et al., 2025).

Concurrent training produces synergistic benefits. When programmed appropriately, combining endurance and resistance training creates superior adaptations compared to either modality alone (Ramos-Campo et al., 2025).

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long before I see improvements in my endurance performance from strength training?

A: Most research shows measurable improvements in running economy within 6-8 weeks of consistent resistance training. However, performance gains in actual competitions may take 8-12 weeks as your body learns to utilize its newfound strength efficiently.

Q: Should I strength train during my competitive season?

A: Yes, but with modifications. Reduce volume and frequency (perhaps 1-2 sessions weekly) to maintain strength gains while prioritizing recovery for competitions. This maintenance approach prevents the detraining effect that occurs when resistance training is completely eliminated.

Q: What's the best time of day to do strength training?

A: The research doesn't show a strong preference, but practical considerations matter. Many athletes find success with morning strength sessions followed by evening endurance work, or vice versa. The key is ensuring adequate spacing (3-6 hours minimum) between high-intensity sessions of different modalities.

Q: Can I do strength training and long runs on the same day?

A: Yes, but be strategic. If doing both, perform the session most important to your current training phase first when you're freshest. Many athletes successfully pair resistance training with easy aerobic sessions rather than intense interval work.

Q: How heavy should I lift as an endurance athlete?

A: Research supports using heavy loads (85%+ of one-rep max) for 2-3 sets of 4-8 repetitions to maximize strength gains and running economy improvements. This is heavier than many endurance athletes traditionally use but produces superior results according to recent meta-analyses (Ramos-Campo et al., 2025).

Q: Will I get too bulky from strength training?

A: No. Endurance training creates a hormonal and metabolic environment that limits excessive muscle hypertrophy. You'll gain functional lean mass that improves performance, not bodybuilder-level size. The research shows moderate gains of 2-5% in muscle cross-sectional area are typical for endurance athletes doing concurrent training.

Q: Should I avoid leg day before a big run?

A: Plan your training calendar strategically. Heavy leg training should be at least 48-72 hours before important endurance sessions. However, proper periodization means not scheduling both types of hard sessions immediately adjacent to each other.

Author’s Note

As a clinician my goal in writing this article is to bridge the gap between exercise physiology research and practical, day-to-day application. Metabolic flexibility is not just a concept for athletes—it is a measurable, modifiable marker of metabolic health that affects every patient I see in my practice. Whether it is diabetes, obesity, fatty liver disease, or age-related decline in endurance, I have observed that improving muscle strength consistently leads to improvements in energy regulation, fatigue resistance, and glycemic stability.

The scientific literature continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging data identifying AMPK and PGC-1α as central regulators of mitochondrial function and adaptive fuel use. My intent is to present these mechanisms in a patient-friendly format while preserving scientific accuracy, so readers can appreciate not only what improves metabolic health, but why.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting any new exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Maximize Muscle Growth: Evidence-Based Strength Training Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Lower Blood Pressure Naturally: Evidence-Based Exercise Guide for Metabolic Syndrome | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise vs. Diet Alone: Which is Best for Body Composition? | DR T S DIDWAL

Movement Snacks: How VILPA Delivers Max Health Benefits in Minutes | DR T S DIDWAL

Breakthrough Research: Leptin Reduction is Required for Sustained Weight Loss | DR T S DIDWAL

HIIT Benefits: Evidence for Weight Loss, Heart Health, & Mental Well-Being | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Curovic, I. (2025). The role of resistance exercise-induced local metabolic stress in mediating systemic health and functional adaptations: Could condensed training volume unlock greater benefits beyond time efficiency? Frontiers in Physiology, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2025.1549609

Hammert, W. B., Yamada, Y., Kataoka, R., Song, J. S., Spitz, R. W., Wong, V., Seffrin, A., & Loenneke, J. P. (2025). Changes in absolute and relative muscular endurance after resistance training: A review of the literature with considerations for future research. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 39(4), 474–491. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000005084

Norris, A. M., Palzkill, V. R., Appu, A. B., Fierman, K. E., Noble, C. D., Ryan, T. E., & Kopinke, D. (2025). Intramuscular adipose tissue restricts functional muscle recovery. Cell Reports, 44, 116021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116021

Ramos-Campo, D. J., Andreu-Caravaca, L., Clemente-Suárez, V. J., & Rubio-Arias, J. Á. (2025). The effect of strength training on endurance performance determinants in middle- and long-distance endurance athletes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 39(4), 492–506. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000005056

Zhang, J., Pearson, A. Z., Grunau, M., Beaudry, K. M., Welch, S., Jacobs, R. A., & Broskey, N. T. (2025). The role of muscle mass in endurance performance and neuromuscular fatigue: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 55, 2809–2824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02290-7

Zhao, X., Huang, F., Sun, Y., & Li, L. (2025). Mechanisms of endurance and resistance exercise in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 761, 151731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2025.151731