How to Build Stronger Bones: Why Lean Muscle Mass Matters More Than Weight Loss for Bone Density

How lean muscle mass, fat mass, and body composition affect bone mineral density and bone strength—backed by clinical research

EXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/25/202617 min read

For decades, bone health has been framed almost exclusively through the lens of calcium intake, vitamin D supplementation, and aging-related bone loss. While these factors remain important, emerging research reveals a far more powerful—and often overlooked—determinant of bone mineral density (BMD): body composition, specifically the dynamic balance between lean mass and fat mass. In fact, growing evidence suggests that what your body is made of may matter more for skeletal strength than how much you weigh.

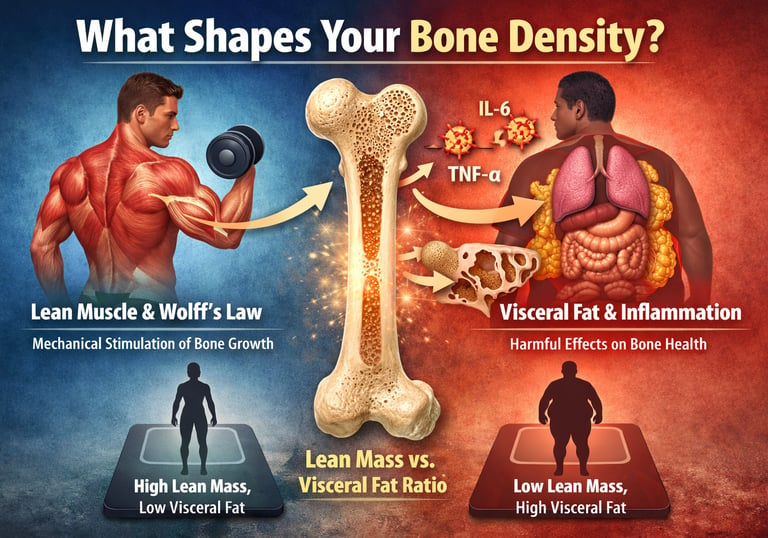

Bones are not inert structures. They are metabolically active tissues that continuously remodel in response to mechanical loading, hormonal signaling, and inflammatory status. Lean body mass—particularly skeletal muscle—plays a central role in this process. Through muscle contraction and force transmission, lean mass provides the primary mechanical stimulus that activates osteoblasts and promotes bone formation, a phenomenon classically described by Wolff’s Law (Gjesdal et al., 2008). Conversely, excess fat mass, especially visceral adipose tissue, exerts complex and sometimes harmful effects on bone through chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and altered endocrine signaling (Li et al., 2023).

This paradox has led to a growing recognition that individuals can present with normal or even elevated BMD yet remain at high fracture risk, particularly in the setting of obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Recent population studies demonstrate that the lean mass–to–visceral fat ratio is a stronger predictor of bone strength than body weight or body mass index alone (Li et al., 2023; Lin & Teng, 2024).

This evidence-based guide explores how lean mass, fat mass, fat distribution, sex, and age interact to shape bone mineral density across the lifespan—challenging outdated assumptions and redefining what it truly means to build strong, resilient bones.

Clinical Pearls

1. Muscle is Your Bone's Best Investment

The Science: Bone strength is fundamentally determined by mechanical loading, a principle known as Wolff's Law. Your muscles are the engine of this process. Every time you perform resistance training, your muscles pull on the attached bones, stimulating specialized cells called osteoblasts to build denser bone tissue (Gjesdal et al., 2008). [Image illustrating muscle pulling on bone, highlighting Wolff's Law and mechanical stimulation]

The Pearl: If you want stronger bones, you must build and maintain muscle. Prioritize strength training (lifting weights, using resistance bands) 2-3 times per week. This effort is more critical for your long-term bone density than consuming extra calcium alone.

2. Focus on Composition, Not Just the Scale

The Science: Two people can weigh the same but have vastly different bone health. Research confirms that the lean mass to visceral fat ratio is a stronger predictor of bone mineral density (BMD) than total weight or BMI (Li et al., 2023). Excess visceral fat releases inflammatory chemicals that compromise bone quality, leading to the "obesity paradox" (dense, yet weak bones).

The Pearl: Don't let the scale mislead you. The goal is to maximize lean mass while reducing harmful visceral fat. Seek out a body composition assessment (like a DEXA scan) to know your true ratio and target your exercise and diet for muscle preservation.

3. Visceral Fat is Bone’s Worst Enemy

The Science: Not all fat is equal. Visceral fat (fat stored around internal organs) is metabolically active and releases high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (like IL-6). These chemicals directly activate osteoclasts, the cells responsible for breaking down bone (Gjesdal et al., 2008). [Image illustrating the location of visceral fat surrounding internal organs versus subcutaneous fat]

The Pearl: Focus on metabolic health to reduce your riskiest fat. Reducing refined carbohydrates, improving sleep, and increasing physical activity are the best ways to target visceral fat, thus reducing the chronic inflammation that compromises your bone quality.

4. The Youth Advantage is Achievable at Any Age

The Science: Achieving peak bone mass during adolescence and young adulthood establishes a lifelong advantage (Ma et al., 2024). However, studies show that maintaining and building lean mass in middle and older age remains the most effective strategy for preventing age-related decline in BMD (Garvey et al., 2022).

The Pearl: You can't change your youth, but you can change your future. While peak bone mass is set early, your ability to preserve and strengthen your skeleton through consistent resistance training never disappears. Every decade you stay active is an investment that reduces your fracture risk later in life.

5. Strategies Need to Be Sex-Specific

The Science: Research indicates that the relationship between body composition and bone strength differs by sex (Lin & Teng, 2024). Females show a particular vulnerability where visceral fat has a highly detrimental effect on bone quality, interacting with estrogen-dependent mechanisms. Males generally show a stronger, more direct relationship between lean mass and bone strength.

The Pearl: Tailor your plan. While resistance training is essential for everyone, women should place an extra emphasis on lifestyle strategies that specifically target the reduction of visceral fat alongside muscle maintenance, especially after menopause, to protect against accelerated bone breakdown.

6. The "Goldilocks" Ratio: Muscle, Fat, and Sex Differences

The Science: A 2025 study found that the Skeletal Muscle-to-Visceral Fat Ratio (SVR) is the most accurate predictor of bone density. However, the "ideal" ratio depends on sex: men see linear gains (more muscle always equals stronger bones), while premenopausal women have a "Goldilocks Zone" 0.31 kg/cm If a woman's ratio is too high (extreme leanness), bone density can actually plateau or drop due to lost estrogen support (Jin et al., 2025).

The Pearl: Don't just chase "weight loss"—chase ratio optimization. Men should focus on maximum muscle gain to protect their skeletons. Women should aim for high muscle mass but avoid extreme fat loss, as a healthy "buffer" of fat is necessary to maintain the hormones that keep bones from becoming brittle

The Complete Guide to Understanding How Lean Mass and Fat Mass Impact Bone Mineral Density

Understanding the Fundamentals: Bone Mineral Density Explained

Before diving into the relationship between body composition and bone strength, let's establish what we're actually measuring. Bone mineral density (BMD) represents the amount of minerals—primarily calcium and phosphorus—packed into a specific volume of bone tissue. It's typically measured using a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan, commonly known as a DXA scan or DEXA scan.

Think of BMD as a measure of bone quality and density. Higher BMD generally indicates stronger bones less vulnerable to fracture, while lower BMD may suggest increased fracture risk. However—and this is crucial—BMD alone doesn't tell the complete story. The composition of your body, particularly your muscle mass versus adipose tissue, dramatically influences how dense your bones become and how well they withstand mechanical stress.

Your bones aren't static structures. They're constantly remodeling in response to the forces placed upon them. This is where lean mass becomes extraordinarily important. When muscles contract and exert force on bones, they stimulate the bone-building process, prompting specialized cells called osteoblasts to create new bone tissue. Meanwhile, fat mass plays a more complex role, influencing hormones and inflammatory markers that affect bone metabolism in ways researchers are still untangling.

While dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) remains the clinical gold standard for assessing bone mineral density, it is important to recognize its inherent limitation: DXA measures areal BMD (g/cm²) rather than true volumetric BMD (g/cm³). As a two-dimensional projection technique, DXA cannot fully account for bone depth, geometry, or microarchitectural properties. Consequently, individuals with larger body size, greater lean mass, or higher adiposity may appear to have higher BMD despite potential differences in bone quality or strength. Advanced imaging modalities such as quantitative computed tomography (QCT) and high-resolution peripheral QCT (HR-pQCT) provide volumetric and structural insights but are less accessible in routine clinical practice.

The Role of Lean Mass in Building and Maintaining Bone Strength

Lean body mass—comprising muscle, bone, organs, and water—is perhaps the most direct modifiable factor influencing bone mineral density. The relationship between these variables is supported by compelling research spanning multiple populations and age groups.

Mechanical Loading: The Muscle-Bone Connection

Here's the physiological reality: muscles are the primary force that stimulates bone formation. Every time you contract a muscle, you create mechanical stress on the bones to which that muscle attaches. Your skeleton responds to this stress by increasing bone mineral density in those specific locations. This principle, known as Wolff's Law, has been understood for over a century but is increasingly validated by modern imaging and biomarker research.

Consider what happens during resistance training. The repeated mechanical loading places demands on your skeletal system, triggering a cascade of adaptations that strengthen bones. This isn't limited to professional athletes—even moderate regular strength training produces measurable improvements in BMD. Conversely, conditions characterized by muscle loss, such as aging or prolonged inactivity, typically result in declining bone mineral density and increased fracture risk.

Growth Factor Signaling and Systemic Effects

Beyond mechanical loading, lean mass influences bone mineral density through endocrine pathways. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, producing hormones and growth factors that regulate bone turnover. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), largely produced by muscle tissue, stimulates osteoblasts and promotes bone formation. Greater lean body mass generally correlates with higher circulating IGF-1 levels, creating a favorable hormonal environment for bone health.

Additionally, muscle tissue produces myokines—specialized signaling molecules that influence bone metabolism throughout the body. This emerging field of research suggests that lean mass functions as an endocrine organ, actively communicating with skeletal tissue to maintain and enhance bone mineral density.

The Complex Role of Fat Mass in Bone Metabolism

The relationship between fat mass and bone mineral density is considerably more nuanced than that of lean mass, and research shows this relationship varies meaningfully across populations and age groups. Understanding these complexities is essential for developing effective bone health strategies.

The Paradox of Obesity and BMD

One of the most intriguing findings in bone metabolism research is the "obesity paradox." Many obese individuals show elevated bone mineral density compared to their lean counterparts—yet they paradoxically experience higher fracture rates. How can bones be dense yet fragile?

The answer lies in distinguishing between bone mineral density and bone quality. While fat mass does appear to stimulate increased BMD through mechanical loading (bones must support greater weight) and hormonal effects, this added density doesn't necessarily translate to superior bone strength. Obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and altered vitamin D metabolism can compromise bone quality despite adequate density.

Specifically, excess adipose tissue produces pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which activate osteoclasts—cells responsible for bone breakdown. This creates a state of elevated bone turnover where density may increase but structural integrity suffers. The bones become simultaneously dense and weak—a concerning combination.

Visceral Fat and Systemic Inflammation

Not all fat is equivalent in its effects on bone health. Visceral fat mass—the metabolically active fat surrounding internal organs—appears particularly detrimental to bone quality despite its relationship with BMD. This distinction has profound implications for understanding body composition and bone health.

Visceral adiposity correlates strongly with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and systemic inflammation—all factors that compromise bone metabolism. The lean-to-visceral-fat ratio emerges as potentially more clinically meaningful than simple weight or total fat mass measurements. Higher ratios (more lean, less visceral fat) associate with superior bone mineral density and bone quality markers.

Hormonal Modulation and Estrogen

Adipose tissue functions as an endocrine organ, producing estrogen through peripheral aromatization. While adequate estrogen supports bone health—explaining why postmenopausal women often experience BMD declines—excess adipose tissue–derived estrogen doesn't necessarily produce benefits. The quality and distribution of this hormone production matters considerably.

Furthermore, fat mass influences adiponectin production, a hormone with apparent protective effects on bone. However, the relationship isn't linear—extremely low and extremely high adiponectin levels may both compromise bone health. This indicates that optimal bone mineral density exists within specific body composition ranges, not simply at the extreme of leanness.

Key Research Findings: What Studies Tell Us About Body Composition and Bone Health

Study 1: Young Overweight and Obese Women—Disentangling Lean and Fat Effects

Research examining bone mineral density, lean body mass, fat mass, and physical activity in young overweight and obese women (Garvey et al., 2022) provides critical insights into how these variables interact in a population experiencing rapid metabolic shifts.

Key findings: Among young women, lean mass demonstrated a strong positive correlation with bone mineral density at multiple skeletal sites. Importantly, when lean and fat mass were analyzed together, lean mass emerged as the dominant predictor of BMD—even after accounting for total body weight (Garvey et al., 2022). Physical activity further enhanced this relationship, with active women showing higher bone mineral density for equivalent lean body mass levels.

The implications are significant: for bone health in this population, acquiring and maintaining muscle mass through resistance training provides greater benefit than weight loss alone. Women who maintained high lean body mass while reducing fat mass showed the most favorable bone mineral density values.

Key takeaway: In young women, prioritizing lean mass development through strength training appears more beneficial for bone health than focusing solely on weight reduction or caloric restriction.

Study 2: The Lean-to-Visceral-Fat Ratio—A More Nuanced Approach

A cross-sectional analysis of United States population data revealed that the lean body mass to visceral fat mass ratio independently predicted bone mineral density across diverse age groups and ethnic backgrounds (Li et al., 2023).

Key findings: The ratio demonstrated stronger associations with BMD than simple measurements of total fat mass or lean mass alone (Li et al., 2023). Individuals with elevated lean-to-fat ratios consistently showed higher bone mineral density and lower fracture risk markers. Notably, the relationship held even after adjusting for total body weight—suggesting that weight alone is insufficient for understanding bone health.

This research elegantly demonstrates that body composition quality matters more than composition quantity. Two individuals at identical weights but with different lean-to-fat ratios show markedly different BMD profiles.

Key takeaway: Evaluate body composition using ratios rather than absolute measurements, and prioritize improving your lean-to-visceral-fat ratio as a primary bone health objective.

Study 3: The Hordaland Health Study—Comprehensive Population Analysis

A comprehensive population study tracked relationships between lean mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density across diverse age groups and sexes (Gjesdal et al., 2008).

Key findings: Lean mass consistently demonstrated strong positive associations with BMD across all age groups and skeletal sites (Gjesdal et al., 2008). Fat mass showed more complex, age-dependent relationships—protective in younger individuals but increasingly detrimental to bone quality with advancing age. This temporal shift reflects changing metabolic function and shifting contributions of mechanical loading versus metabolic factors across the lifespan.

Women displayed different body composition–BMD relationships compared to men, with postmenopausal women showing particular sensitivity to lean mass levels. The findings suggest that maintaining adequate lean body mass becomes increasingly critical for bone health with aging.

Key takeaway: The importance of lean mass for bone health intensifies throughout the lifespan, making sustained muscle maintenance a lifelong bone health investment.

Study 4: High Fat and Low Lean Mass Phenotype in Chinese Adolescents

An investigation of Chinese adolescents revealed how body composition patterns established during youth persist and influence bone development trajectories (Ma et al., 2024).

Key findings: Adolescents characterized by high fat mass and low lean mass phenotypes demonstrated meaningfully reduced bone mineral content despite normal or slightly elevated total body weight (Ma et al., 2024). This observation proves critical: weight-for-age normal adolescents can still develop insufficiently mineralized skeletons if body composition is unfavorable.

The research suggests that childhood interventions emphasizing lean mass development through physical activity and strength training may establish bone health trajectories with lifelong implications.

Key takeaway: During growth years, establishing favorable body composition through muscle development is essential for achieving peak bone mass and protecting skeletal health throughout life.

Study 5: Muscle-Fat Ratio & Bone Health: Sex Differences

This recent study by Jin et al. (2025) provides a critical update to our understanding of how muscle and fat interact to influence bone health, specifically within the middle-aged demographic (ages 40–59).

Using data from 4,349 participants, the researchers utilized a novel composite metric: the Skeletal Muscle Mass-to-Visceral Adipose Tissue Area ratio (SVR). This ratio reflects the balance between "bone-building" muscle and "bone-eroding" visceral fat.

The General Trend: Skeletal muscle mass (SMM) is positively correlated with bone mineral density (BMD), while visceral adipose tissue area (VATA) is inversely related

Sex-Specific Differences in SVR:

In Men: There is a direct, positive linear relationship between SVR and BMD. As the muscle-to-fat ratio increases, bone density consistently improves

In Premenopausal Women: The relationship is non-linear (inverted U-shaped). BMD is optimized when SVR reaches a specific threshold. 0.31/ kg/cm} Beyond this point, an excessively high ratio may not provide further benefits and could potentially disrupt hormonal equilibrium

The SVR Advantage: The study suggests that SVR is a more effective predictor of lumbar BMD than looking at muscle or fat in isolation, as it accounts for the "physiological interplay" between these two tissues

This research highlights that for middle-aged adults, the goal isn't just "weight loss" or "muscle gain," but achieving a sex-specific balance. For men, the focus should remain on maximizing muscle relative to visceral fat. For premenopausal women, the findings suggest a "Goldilocks zone" where bone health is most resilient.

Study 6: Sex Differences in Fat and Lean Contributions to Bone Strength

Recent research investigating sex-dependent differences revealed that fat and lean mass contribute differently to bone strength in males versus females (Lin & Teng, 2024).

Key findings: Males showed stronger relationships between lean mass and bone strength markers, while females demonstrated more complex interactions involving estrogen-dependent mechanisms and fat mass hormonal effects (Lin & Teng, 2024). Visceral fat mass appeared particularly detrimental to bone quality in females, suggesting sex-specific metabolic vulnerabilities.

These findings explain partially why simple body composition recommendations often fail—optimal strategies necessarily differ between sexes.

Key takeaway: Bone health strategies should be sex-specific, with women particularly benefiting from attention to visceral fat reduction alongside lean mass development.

Practical Implications: Translating Research into Action

Optimizing Body Composition for Bone Health

Based on synthesized research findings, several evidence-based strategies emerge for optimizing body composition to maximize bone mineral density:

Prioritize resistance training: Regular strength training with progressive resistance challenges your muscles and directly stimulates osteoblast activity and bone mineral density development. Aim for 2-3 sessions weekly targeting major muscle groups.

Maintain adequate protein intake: Muscle tissue requires amino acids for synthesis and maintenance. Consuming 0.8-1.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight supports lean mass preservation during dieting or aging.

Include weight-bearing cardiovascular activity: Running, hiking, and jumping activities create mechanical loading that stimulates bone mineral density increases. Combine these with resistance training for complementary benefits.

Monitor body composition rather than weight alone: Seek to increase or maintain lean body mass while reducing fat mass—a combination that optimizes BMD. Two individuals at identical weights might have vastly different bone health based on their body composition distribution.

Consider fat distribution, not just total fat mass: Focus on reducing visceral fat through reduced refined carbohydrate consumption, increased physical activity, and adequate sleep—measures that improve metabolic health beyond simple weight loss.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lean Mass, Fat Mass, and Bone Health

Q: I'm trying to lose weight. Will weight loss harm my bones?

A: Weight loss can challenge bone health if accomplished through caloric restriction without attention to preserving lean mass. However, weight loss that maintains or increases muscle mass through resistance training while reducing fat mass actually improves bone mineral density. The key is preserving or building lean body mass during the weight loss process.

Q: Can I have high BMD but still have weak bones?

A: Yes—the "obesity paradox" demonstrates exactly this scenario. High BMD doesn't guarantee bone strength if bone quality is compromised. Obese individuals often show elevated BMD due to increased mechanical loading but may experience frequent fractures due to poor bone quality from chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. Bone quality and bone mineral density are distinct properties.

Q: At what age should I start caring about my body composition for bone health?

A: The answer is "now," regardless of age. During youth and young adulthood, building maximum lean body mass establishes a lifelong bone health advantage through peak bone mass optimization. During middle age and beyond, maintaining lean mass becomes essential for preventing age-related declines. At every life stage, body composition influences bone health.

Q: Is fat mass entirely bad for bones?

A: No—healthy fat mass contributes to bone health through hormonal signaling, estrogen production, and mechanical support. The problem emerges with excess fat mass, particularly visceral fat, which triggers inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. Optimal bone health exists within healthy body composition ranges, not at extremes of either excessive leanness or obesity.

Q: Does sex influence how body composition affects bones?

A: Definitively yes. Females show particular sensitivity to visceral fat mass effects on bone quality, and estrogen's role in bone metabolism creates sex-specific vulnerabilities. Males generally show stronger lean mass–bone health relationships. Effective strategies recognize these differences.

Q: What's the most important factor for my bone health: weight loss or muscle building?

A: Research consistently indicates that lean mass development has stronger associations with improved bone mineral density than weight reduction alone. If you must choose between focusing on weight loss versus muscle development, prioritize building and maintaining lean body mass through resistance training, as this directly stimulates bone formation through mechanical loading and hormonal signaling.

Key Takeaways: Your Action Plan for Bone Health

Lean mass is your bones' best friend: Among modifiable factors, lean body mass shows the strongest relationship with bone mineral density. Resistance training that builds and maintains muscle is perhaps the single most powerful bone health intervention available.

Body composition matters more than weight: Two individuals at identical weights can have dramatically different bone mineral density based on their body composition. Focus on building lean mass while reducing fat mass, not simply losing weight.

Fat distribution is critical: Visceral fat mass appears more metabolically harmful than subcutaneous fat. Improving your lean-to-fat ratio provides greater bone health benefits than achieving an identical weight through different body composition pathways.

Optimal bone health requires sustained attention across the lifespan: The importance of favorable body composition for bone health persists from adolescence through aging. Peak bone mass achievement during youth establishes lifetime bone health, while sustained lean mass maintenance prevents age-related declines.

Combine multiple strategies: Resistance training, adequate protein intake, weight-bearing activity, and metabolic health optimization work synergistically to support optimal bone mineral density and bone quality.

Individual responses vary by sex and age: Effective bone health strategies account for sex-specific differences in how lean mass and fat mass influence skeletal health and consider how these relationships shift across the lifespan.

Author’s Note

Bone health is too often discussed in isolation—reduced to calcium intake, vitamin D levels, or chronological aging. Yet decades of metabolic, endocrine, and musculoskeletal research clearly demonstrate that bones do not exist independently of the body that surrounds them. They respond dynamically to muscle forces, hormonal signals, inflammatory mediators, and overall metabolic health. This article was written to bridge that gap—to move the conversation beyond simplistic explanations and toward a body composition–centered understanding of bone mineral density.

The goal of this guide is not merely to summarize existing research, but to integrate physiology, epidemiology, and clinical relevance into a practical framework that clinicians, researchers, fitness professionals, and health-conscious readers can apply. Particular emphasis has been placed on the differential roles of lean mass, fat mass, and visceral adiposity, as well as on sex- and age-specific variations that are often overlooked in generalized recommendations.

While the studies cited are robust and drawn from diverse populations, it is important to acknowledge that much of the current evidence is observational. Bone health is multifactorial, and individual responses may vary based on genetics, nutrition, hormonal status, physical activity patterns, and underlying medical conditions. Therefore, the information presented here should be viewed as a scientific foundation for informed decision-making, not a substitute for individualized medical evaluation.

Ultimately, this work reflects a central message supported by modern bone biology: strong bones are built through movement, muscle, and metabolic health. By understanding and optimizing body composition across the lifespan, we gain a powerful, evidence-based opportunity to preserve skeletal strength and reduce fracture risk well into older age.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting any new exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Maximize Muscle Growth: Evidence-Based Strength Training Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Lower Blood Pressure Naturally: Evidence-Based Exercise Guide for Metabolic Syndrome | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise vs. Diet Alone: Which is Best for Body Composition? | DR T S DIDWAL

Movement Snacks: How VILPA Delivers Max Health Benefits in Minutes | DR T S DIDWAL

Breakthrough Research: Leptin Reduction is Required for Sustained Weight Loss | DR T S DIDWAL

HIIT Benefits: Evidence for Weight Loss, Heart Health, & Mental Well-Being | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Jin, F., Gao, S., Yao, X. et al. Sex-specific associations between muscle-fat ratio and bone density in middle-aged adults. Sci Rep 15, 29105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15069-7

Garvey, M. E., Shi, L., Lichtenstein, A. H., Must, A., Hayman, L. L., Crouter, S. E., & Camhi, S. M. (2022). Association of bone mineral density with lean mass, fat mass, and physical activity in young overweight and obese women. International Journal of Exercise Science, 15(7), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.70252/POYU6849

Gjesdal, C. G., Halse, J. I., Eide, G. E., Brun, J. G., & Tell, G. S. (2008). Impact of lean mass and fat mass on bone mineral density: The Hordaland Health Study. Maturitas, 59(2), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.11.002

Li, L., Zhong, H., Shao, Y., Zhou, X., Hua, Y., & Chen, M. (2023). Association between lean body mass to visceral fat mass ratio and bone mineral density in United States population: a cross-sectional study. Archives of Public Health, 81(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01190-4

Lin, Y. H., & Teng, M. M. H. (2024). Different contributions of fat and lean indices to bone strength by sex. PLoS ONE, 19(11), e0313740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0313740

Ma, X., Tian, M., Liu, J., Tong, L., & Ding, W. (2024). Impact of high fat and low lean mass phenotype on bone mineral content: A cross-sectional study of Chinese adolescent population. Bone, 186, 117170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2024.117170