Body Recomposition Explained: A Doctor’s Evidence-Based Guide to Getting Leaner and Stronger

Discover the science of body recomposition. A doctor’s evidence-based guide to losing fat, building muscle, and improving metabolic health.

EXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/2/202614 min read

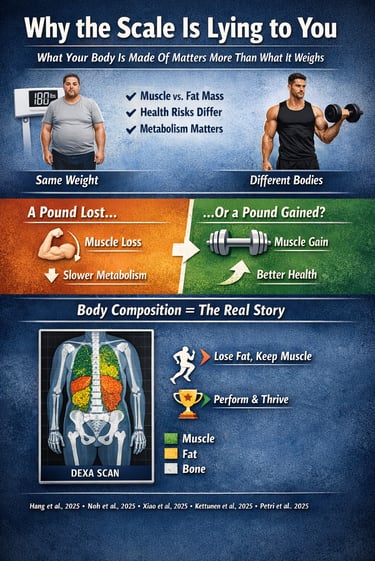

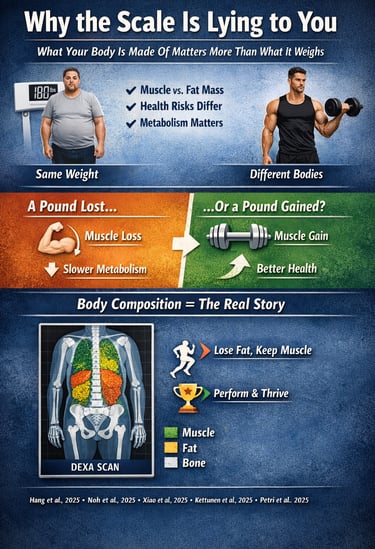

Step on the scale after weeks of disciplined training and careful nutrition, and the number barely changes. For many, this moment signals failure. Yet modern exercise science suggests the opposite: the scale may be missing the most important physiological changes occurring beneath the surface.

For decades, body weight has been used as the primary marker of health and fitness. However, contemporary research shows that individuals with identical body weights can differ dramatically in strength, metabolic health, insulin sensitivity, and disease risk, depending on their body composition—that is, the proportion of fat mass to lean muscle mass (Hang et al., 2025; Noh et al., 2025). What matters is not how much the body weighs, but what the body is made of.

This concept forms the basis of body recomposition, defined as the simultaneous reduction of fat mass with the gain or preservation of lean muscle. Once believed to be limited to beginners or athletes, body recomposition is now recognized as achievable across a wide range of ages and fitness levels when evidence-based training and nutrition strategies are applied (Noh et al., 2025).

Skeletal muscle is far more than a mechanical tissue. It functions as a critical metabolic organ, regulating glucose disposal, resting energy expenditure, and inflammatory signaling, while protecting against age-related sarcopenia and metabolic decline (Xiao et al., 2025). In contrast, excess adipose tissue—particularly visceral fat—contributes to insulin resistance, systemic inflammation, and cardiometabolic disease risk (Hang et al., 2025).

Emerging research in both clinical populations and elite athletes demonstrates that optimizing body composition, rather than focusing on scale weight alone, leads to superior health and performance outcomes (Kettunen et al., 2025; Petri et al., 2025). This article explores the science of body recomposition, drawing on recent randomized trials, meta-analyses, and performance studies to explain how resistance training, aerobic exercise, and adequate protein intake work synergistically to help individuals become leaner, stronger, and metabolically healthier—regardless of what the scale shows.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Metabolic Engine" Preservation

Scientific Perspective: Resistance training during caloric deficit induces myofibrillar protein synthesis, which counteracts the catabolic signaling that typically leads to lean mass loss during weight reduction. This preserves the Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), ensuring that the majority of weight lost is derived from adipose tissue rather than functional muscle.

When you lose weight by just eating less, your body often "eats" its own muscle for energy. Lifting weights acts like an insurance policy; it tells your body, "I’m still using these muscles, so burn the fat instead." This keeps your metabolism high, so you don't just gain the weight back the moment you stop dieting.

2. Visceral Fat vs. Subcutaneous Fat

Scientific Perspective: While resistance training is superior for lean mass accretion, aerobic training shows higher efficacy in reducing visceral adipose tissue (VAT). VAT is metabolically active and pro-inflammatory; its reduction via aerobic pathways significantly improves systemic insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular risk profiles.

There are two types of fat: the kind you can pinch (subcutaneous) and the dangerous kind hidden deep around your organs (visceral). Lifting makes you look better and stronger, but cardio is the "clean-up crew" for that hidden organ fat that causes heart disease and diabetes. You need both to be truly healthy.

3. The "Ceiling" of Protein Efficiency

Scientific Perspective: For endurance athletes, the anabolic window is less about immediate muscle growth and more about mitochondrial repair. Supplementation of 1.6–2.0 g/kg/day of protein is required to maintain a positive nitrogen balance during high-volume training, preventing the "overtraining syndrome" associated with lean mass wasting.

If you are running or cycling a lot, you are actually "wearing down" your muscles. You don't need protein shakes to look like a bodybuilder; you need them to repair the damage from your long runs. Think of protein as the "maintenance crew" that fixes the road after a long day of heavy traffic.

4. Running Economy and Lean Mass Distribution

Scientific Perspective: In elite endurance contexts, body composition optimization is not a quest for the lowest weight, but the highest power-to-weight ratio. Lower-body lean mass contributes to musculotendinous stiffness, which enhances the stretch-shortening cycle, thereby improving running economy and reducing the oxygen cost of submaximal exercise.

Being "skinny" isn't the same as being "fast." Having strong, lean muscles in your legs makes them act like springs. Instead of your feet "thudding" onto the ground, they "boing" back up. This means you can run faster while using less oxygen, which is the secret to a new personal best.

5. The Limitations of BMI (Body Mass Index)

Scientific Perspective: BMI fails to account for tissue quality or distribution, often misclassifying muscular individuals as "overweight" (the "False Positive") or individuals with low muscle mass/high fat as "healthy" (the "False Negative" or Normal Weight Obesity). Kinanthropometry and DEXA provide a multi-compartment model that is a far superior predictor of clinical health and athletic power.

The scale is a liar because it can't tell the difference between five pounds of muscle and five pounds of fat. You could weigh exactly the same as you did three months ago but be two sizes smaller and significantly healthier. Stop chasing a number on the scale and start focusing on how your clothes fit and how strong you feel.

Section 1: Resistance Training vs. Aerobic Training for Weight Loss and Body Composition

Over the past decade, exercise science has undergone a revolution. We now understand that not all weight is created equal. Two people weighing 200 pounds can have dramatically different health profiles depending on how much of that weight is lean muscle mass versus body fat. Recent 2025 research from leading institutions reveals fascinating insights into how different types of exercise reshape your body, improve your physical fitness, and enhance your overall health.

Whether you're a middle-aged adult struggling with obesity, an elite endurance athlete seeking performance gains, or someone simply wanting to understand the science behind fitness, this comprehensive guide breaks down the latest evidence in language everyone can understand.

What the Latest Research Shows

A groundbreaking examined one of fitness's most fundamental questions: which training method actually works better for improving body composition in middle-aged adults with obesity?

Study Details: Hang et al. (2025) conducted an interventional study specifically designed to compare the effects of resistance and aerobic training on body composition in adults with obesity. This wasn't a small study—researchers carefully measured changes in muscle mass, fat mass, and overall body composition across a large cohort of middle-aged participants.

The results challenge a common myth: you don't have to choose between them. Both resistance training and aerobic training effectively improved body composition, but they worked slightly differently:

Resistance training proved exceptionally effective at preserving and building lean muscle mass while reducing overall body weight

Aerobic training excels at reducing total body fat, particularly stubborn visceral fat (the dangerous fat around your organs)

Combined approaches yielded superior results compared to either method alone

What This Means for You: If you're overweight or obese, this research validates a balanced approach. Spend 2-3 days per week doing resistance training to protect your muscles while losing weight, and incorporate 150+ minutes of aerobic training weekly to maximize fat loss. The combination is scientifically superior to choosing just one.

The Science Behind Why This Works

When you lose weight through aerobic exercise alone, you may lose muscle along with fat. Resistance training acts as a protective mechanism, signaling your body that those muscles are essential, so it preferentially burns fat instead. This is why combining both creates the optimal stimulus for recomposition—losing fat while maintaining or building muscle.

Section 2: Body Composition in Elite Athletes—Performance Goes Beyond the Scale

While weight management obsesses most people, elite endurance athletes face the opposite problem: understanding how body composition directly impacts physical performance at the highest levels.

Study Details: Kettunen et al. (2025) investigated the associations between body composition and performance in elite endurance athletes. Using sophisticated body-composition assessment tools, researchers analysed whether certain ratios of muscle, fat, and other tissues actually predicted who performed best in distance running, cycling, and other endurance sports.

Key Findings and Takeaways

The relationship between body composition and athletic performance proved more nuanced than "lighter is better":

Elite endurance athletes with slightly more lean muscle mass in the lower body showed superior running economy (how efficiently they used energy)

Excessive low body fat actually correlated with decreased performance, suggesting an optimal range rather than a minimum

Body composition variations within elite athlete ranges had meaningful performance implications—small changes mattered at elite levels

What This Means for You: If you're an athlete, this research shows that body composition optimization isn't about hitting the lowest possible body fat percentage. Instead, focus on the composition that maximizes your sport-specific strength and power while maintaining adequate energy reserves. Coaches and athletes should monitor body composition rather than just scale weight.

Why Body Composition Matters More Than Weight for Athletes

Elite athletes understand what casual exercisers sometimes miss: five pounds of added muscle—even if it increases scale weight—can dramatically improve physical performance. Conversely, losing five pounds of muscle through inadequate nutrition might make you lighter but significantly slower. Body composition assessment tools reveal these distinctions that scales simply cannot.

Section 3: How Exercise Type Shapes Men's Physical Fitness and Body Composition

While individual studies provide valuable insights, sometimes the clearest picture emerges from synthesizing decades of research. That's exactly what Noh et al.(2025) accomplished with their systematic review and meta-analysis examining how different exercise types affect men's physical fitness and body composition.

Study Details: This comprehensive analysis examined dozens of studies comparing resistance training, aerobic training, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), and combined approaches. By pooling results across thousands of male participants, the researchers could identify patterns and overall effects that individual studies might miss.

The meta-analysis revealed several important truths about exercise and body composition:

Resistance Training Effects:

Most effective for building lean muscle mass and increasing muscle strength

Average gains of 2-4 pounds of muscle over 8-12 weeks with proper training

Superior for elevating resting metabolic rate (burning more calories at rest)

Better than aerobic training for preserving muscle during weight loss

Aerobic Training Effects:

Most effective for reducing body fat, particularly visceral fat

Improved cardiovascular fitness and aerobic capacity

Better for overall calorie expenditure during workouts

Synergistic with resistance training for optimal body composition changes

Combined Training Approaches:

Combining resistance training and aerobic training produced the greatest improvements in body composition

Better outcomes for both muscle gain and fat loss simultaneously

Superior improvements in physical fitness markers across the board

What This Means for You: The research consensus is clear: the best exercise program combines both resistance training and aerobic training. A balanced week might look like: 2-3 days of resistance training (strength work), 3-4 days of aerobic training (cardio), and adequate rest days. This combination optimizes body composition, muscle mass, and overall health.

Section 4: Protein Supplementation During Endurance Training—Maximizing Adaptations

The Endurance Athlete's Question: Do I Need Extra Protein?

Endurance training presents a unique challenge: intense aerobic activity demands massive energy expenditure, but it can also trigger muscle breakdown if nutritional support isn't adequate. A critical question emerges: does protein supplementation actually enhance body composition, physiological adaptations, and performance during endurance training?

Study Details: Xiao et al. (2025) conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining protein supplementation effects during endurance training. This analysis included diverse populations from recreational joggers to elite marathon runners, across dozens of controlled interventions.

The research painted a clearer picture than many athletes might expect:

Body Composition Changes:

Protein supplementation during endurance training helped preserve lean muscle mass during intense training periods

Participants receiving adequate protein (1.6-2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight daily) showed better muscle retention

Fat loss remained consistent, but muscle sparing made the overall body composition improvement more favorable

Physiological Adaptations:

Protein supplementation enhanced mitochondrial adaptations (the powerhouse of cells that generates energy)

Improved recovery between training sessions

Better maintenance of immune function during high-volume training

Enhanced hormone production supporting recovery

Performance Improvements:

Mixed but meaningful effects on performance

Greatest benefits appeared in athletes doing high-volume training (10+ hours weekly)

Moderate improvements in running economy and time trial performance

Individual responses varied based on baseline protein intake

What This Means for You: If you engage in endurance training of more than 8-10 hours weekly, protein supplementation likely provides genuine benefits. However, casual runners doing 3-5 hours weekly may achieve adequate protein intake through food alone. The sweet spot for most endurance athletes: consume 1.6-2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, distributed across meals or supplemented as needed.

Practical Protein Strategies for Endurance Athletes

Rather than viewing protein as a single supplement, think of it as a strategic tool. Elite endurance athletes combine three approaches:

Whole food sources (chicken, fish, eggs, Greek yogurt) for primary protein intake

Protein supplementation (whey, plant-based powders) for convenience and post-workout windows

Timing strategies (consuming protein within 30-60 minutes of training) to maximize muscle adaptation

Section 5: Body Composition Assessment in Elite Athletes—The Kinanthropometry Revolution

You might have noticed that throughout this article, we've discussed body composition assessment as though it's a straightforward measurement. But how exactly do researchers and coaches actually measure body composition precisely enough to guide elite athletes' training?

Study Details: Petri et al.(2025) examined body composition and physical performance in elite male rugby referees using kinanthropometry—the sophisticated science of measuring human body dimensions and composition. This study exemplifies how elite sport uses advanced assessment methods to optimize performance and health.

While rugby referees might seem like an unusual focus, the methods and findings apply broadly to any athlete seeking precise body composition assessment.

Key Findings and Takeaways

Assessment Methods Revealed:

Kinanthropometry uses precise measurements of limb circumferences, bone diameters, skinfolds, and segment lengths

Provides much greater detail than simple body weight or BMI

Identifies whether someone is "stocky" (more bone and muscle density) versus "lean" (low body fat but possibly lower muscle mass)

Shows how body composition distribution affects position-specific physical demands

Body Composition and Performance Links:

Elite rugby referees with optimized body composition for their role showed superior endurance capacity

Specific ratios of upper-to-lower body mass predicted agility and change-of-direction speed

Kinanthropometry proved more predictive of physical performance than simple body weight

Practical Applications:

Kinanthropometry assessments should guide exercise programming for athletes

Rather than generic "ideal body weights," athletes benefit from position and sport-specific targets

Regular kinanthropometry assessments track whether training is creating desired body composition changes

What This Means for You: If you're serious about athletic performance, generic metrics like BMI or scale weight simply aren't sufficient. Advanced body composition assessment reveals the detailed picture of your physical makeup. While not every casual exerciser needs professional kinanthropometry, serious athletes benefit enormously from these assessments. Many gyms now offer DEXA scans or bioelectrical impedance analysis—far simpler but still more informative than scales alone.

Integrating the Research: A Practical Framework for Body Composition Success

For Weight Loss and Body Composition Improvement (General Population)

Combine both types of training:

2-3 days weekly of resistance training for muscle preservation

150+ minutes weekly of aerobic training for fat loss

This combination optimizes body composition changes

Consider protein intake:

While less critical during moderate training, adequate protein (1.2-1.6 g/kg) supports muscle preservation

Particularly important if doing simultaneous strength and aerobic work

Track body composition, not just weight:

Muscle weighs more than fat—scale weight can be misleading

Body composition assessment reveals true progress

For Elite and Serious Athletes

Sport-specific body composition optimization:

There's no universal "ideal" body fat percentage

Optimize body composition for your specific sport and position

Use advanced assessment like kinanthropometry or DEXA

Protein becomes critical:

Protein supplementation proves valuable for high-volume endurance training

Target 1.6-2.0 g/kg daily if training 8+ hours weekly

Post-workout protein timing matters for recovery

Periodized training works best:

Periodize your training to address specific body composition goals

Build muscle in off-season; optimize for fat loss in preparation phases

Allow recovery to let physiological adaptations fully develop

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know

✓ Both resistance and aerobic training improve body composition—combining them produces superior results compared to either alone

✓ Muscle preservation matters as much as fat loss—when losing weight, resistance training prevents muscle loss

✓ Body composition varies among elite athletes—there's no single "ideal" body fat percentage; optimize for your sport

✓ Protein supports muscle during endurance training—especially valuable for athletes doing 8+ hours weekly

✓ Assessment methods matter—body composition tells a far more complete story than scale weight alone

✓ Consistency trumps perfection—steady adherence to balanced training outperforms occasional intense efforts

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: I'm overweight and want to lose weight. Should I do resistance training, aerobic training, or both?

A: Research clearly shows combined training produces the best results. Start with 2-3 days weekly of resistance training and gradually build to 3-4 days of aerobic training. This prevents muscle loss while maximizing fat loss. Don't view these as competing options—they work synergistically.

Q: How long before I'll see changes in my body composition?

A: Significant body composition changes typically appear within 8-12 weeks of consistent training. However, the first 2-4 weeks may show minimal scale weight change because you're building muscle while losing fat—a favorable trade your scale won't reflect.

Q: Do I need protein powder if I'm doing endurance training?

A: Not necessarily, unless you're training at very high volumes (8+ hours weekly). Most recreational athletes achieve adequate protein intake through food. However, protein supplementation provides convenience if you struggle to consume enough food-based protein.

Q: What's the best body fat percentage to aim for?

A: It depends entirely on your goals and sport. For general health, 18-25% body fat (women) and 10-18% body fat (men) offer excellent health markers. Elite athletes often sit lower, but attempting to reach elite-level body composition without elite-level genetics and training is often unnecessary and potentially counterproductive.

Q: If I lose weight, will I definitely lose muscle?

A: Not if you do resistance training and maintain adequate protein intake. Resistance training signals your body that muscle is necessary, so it preferentially burns fat during weight loss. This is called "body recomposition."

Q: How often should I assess my body composition?

A: Every 4-8 weeks for serious athletes; every 8-12 weeks for general fitness. More frequent assessments don't provide useful information—body composition changes take time. Less frequent assessments make it harder to track progress.

Q: Can you build muscle and lose fat simultaneously?

A: Yes, particularly if you're new to training or returning after a layoff. This "recomposition" process is slower than pure muscle building or fat loss, but it produces superior results for body composition and aesthetics.

Q: What type of resistance training works best?

A: Multi-joint exercises using moderate-to-heavy weights for 6-12 repetitions prove most effective. Focus on compound movements like squats, deadlifts, bench presses, and rows. 2-3 sets per exercise, 2-3 times weekly, provides excellent results.

Author’s Note

This article was written to reframe how we think about fitness, weight loss, and health in an era where the bathroom scale still dominates the conversation. Despite decades of scientific progress, body weight is often treated as a proxy for health, even though modern evidence consistently shows that body composition—the balance between lean mass, fat mass, and their distribution—is far more clinically and physiologically meaningful.

The studies cited here were deliberately selected from recent (2025) interventional trials, systematic reviews, and performance-focused research to reflect the current consensus in exercise physiology and metabolic health. Priority was given to data that translate directly into real-world decision-making: how people should train, how much protein actually matters, and why resistance training is not optional during fat loss.

Importantly, this article aims to bridge two worlds that are often separated—the scientific literature and practical application. Wherever possible, complex mechanisms are paired with patient- and reader-friendly explanations, without diluting scientific accuracy. The goal is not to promote a specific training ideology, diet trend, or aesthetic ideal, but to provide an evidence-based framework that readers can adapt to their own goals, constraints, and health status.

Individual responses to exercise and nutrition vary widely. Genetics, age, sex, medical conditions, medications, and training history all influence outcomes. As such, this content is intended for educational purposes and should complement—not replace—personalized medical or professional guidance.

The central message remains simple and durable: long-term health and performance are shaped not by what the scale says, but by what your body is made of—and how well it functions.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting a exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

How Exercise Rewires Metabolism: Molecular Control of Lipolysis and Lipid Metabolism | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Maximize Muscle Growth: Evidence-Based Strength Training Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Lower Blood Pressure Naturally: Evidence-Based Exercise Guide for Metabolic Syndrome | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise vs. Diet Alone: Which is Best for Body Composition? | DR T S DIDWAL

Movement Snacks: How VILPA Delivers Max Health Benefits in Minutes | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Hang, S., Xiaoyu, L., Jue, W., et al. (2025). Effects of resistance training and aerobic training on improving body composition in middle-aged adults with obesity: An interventional study. Scientific Reports, 15, Article 33972. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11076-w

Kettunen, O., Mikkola, J., & Ihalainen, J. K. (2025). Associations between body composition and performance in elite endurance athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 20(11), 1530–1537. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2024-0506

Noh, K.-W., Seo, E.-K., & Park, S. (2025). Effect of exercise type on men’s physical fitness and body composition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Men’s Health, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.22514/jomh.2025.001

Xiao, Y., Deng, Z., Sun, W., Li, J., & Gao, W. (2025). Effects of protein supplementation on body composition, physiological adaptations, and performance during endurance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 12, Article 1663860. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1663860

Petri, C., Spataro, F., Cancian, A., Tozzi, E., Gori, N., Russo, L., & Campa, F. (2025). Body composition and physical performance: Kinanthropometric assessment of elite male rugby referees. International Journal of Kinanthropometry, 5(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.34256/ijk2531