Train Your Brain: How Exercise Boosts Memory & Focus

Learn how exercise enhances memory, cognition, neuroplasticity, and brain structure. Discover new research linking physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, dementia prevention, and brain aging

EXERCISEAGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/18/202615 min read

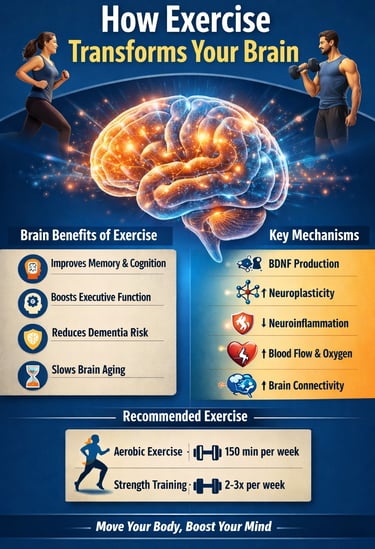

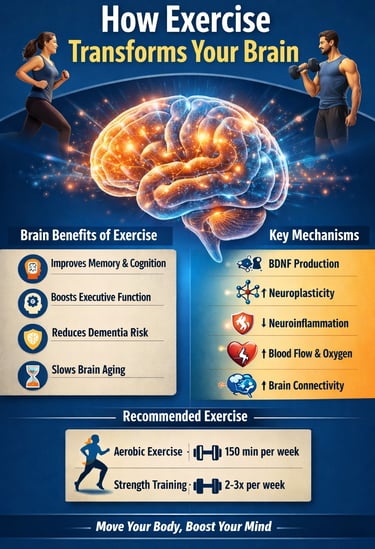

What if the most powerful therapy for boosting memory, sharpening focus, and protecting your brain from aging wasn’t found in a pill bottle—but in your running shoes? Over the past decade, scientists have uncovered a remarkable truth: physical exercise is one of the most potent and reliable interventions for long-term brain health. Far from being just a tool for weight loss or cardiovascular fitness, exercise triggers a cascade of biological responses that strengthen neural networks, enhance cognitive performance, and slow age-related decline (Singh et al., 2025).

Modern neuroscience now shows that every time you engage in physical activity, your brain responds like a high-performance engine being fine-tuned. Blood flow increases, oxygen delivery rises, and neurotrophic factors like BDNF surge—stimulating the growth of new neurons and strengthening existing pathways (Tari et al., 2025). At the same time, neuroinflammation decreases, mitochondrial efficiency improves, and brain regions critical for decision-making, memory, and emotional regulation become more active and better connected (Li et al., 2025).

Even more compelling, large-scale longitudinal research suggests that cardiorespiratory fitness can lower dementia risk—even in people with strong genetic predisposition to cognitive decline (Wang et al., 2025). In other words, your genes may load the gun, but your lifestyle pulls—or refuses to pull—the trigger.

As researchers continue mapping the exercise–brain connection, one message is clear: movement is medicine, and your brain thrives on it. Whether you're 25 or 75, the most important investment you can make in your cognitive future may be the next workout you choose to do.

Clinical pearls

1. Fitness is a "Genetic Buffer"

While we cannot change the DNA we were born with, cardiorespiratory fitness acts as a powerful modifier of genetic expression. Even if you have a family history or a genetic predisposition for Alzheimer’s (such as the APOE-ε4 allele), maintaining high aerobic fitness can significantly lower your actual risk of developing dementia.

The Pearl: Your lifestyle can often "quiet" the influence of your genes.

2. BDNF: The Brain’s Natural "Fertilizer"

When you engage in sustained aerobic exercise, your body produces Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). This protein acts like a fertilizer for your neurons, supporting "synaptic plasticity"—the brain's ability to create new connections and repair old ones.

The Pearl: Exercise is the most effective "drug-free" way to stimulate the growth and survival of your brain cells.

3. Efficiency Over Effort

Highly fit individuals show more "efficient" cortical activation. This means that a fit brain doesn't have to work as hard to perform complex tasks. Using EEG technology, researchers have found that fitness improves your brain’s "resting state," ensuring it is always primed and ready for action without burning unnecessary energy.

The Pearl: Physical fitness doesn't just make your muscles more efficient; it streamlines your brain's electrical circuitry.

4. "Brain Age" is Modifiable

Chronological age (the number on your birthday cake) and biological brain age can be different. Research into "Brain Age" shows that people with high cardiorespiratory fitness often have brains that look and function 10 years younger than their sedentary peers. This remains true even for those already experiencing mild memory concerns.

The Pearl: You can't stop the clock, but you can "de-age" your brain's physical structure through consistent movement.

5. The "Vascular Highway" Effect

Your brain is the most energy-demanding organ in your body, requiring a constant supply of oxygen and glucose. Exercise strengthens the "vascular highway"—the network of blood vessels—ensuring robust cerebral blood flow and reducing neuroinflammation that can "clog" mental processing.

The Pearl: Think of exercise as a "cleansing flush" for your brain’s circulation, removing waste and delivering vital nutrients.

Exercise and Brain Health: How Physical Activity Transforms Your Mind

The Big Picture: What Recent Research Reveals

The relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and brain health has become one of the most exciting areas of neuroscience research. Scientists are no longer asking "Does exercise help the brain?" but rather "How many ways does exercise help the brain?"—and the answers are staggering.

Recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have consolidated findings from hundreds of studies, revealing consistent patterns about how physical activity influences neural function, cognitive performance, and protection against age-related cognitive decline. Let's explore what the latest research tells us.

Study 1: The Definitive Evidence on Exercise and Cognitive Performance

Study: Singh et al. (2025) Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta-Meta-Analysis

Singh and colleagues conducted an ambitious systematic umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of exercise for improving cognition, memory, and executive function. This analysis synthesized data from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, making it one of the most robust assessments of exercise's cognitive benefits.

The research clearly demonstrates that exercise interventions produce significant improvements in:

Cognitive function (overall mental processing and thinking skills)

Memory (both short-term and long-term recall)

Executive function (planning, decision-making, impulse control, and mental flexibility)

The power of this study lies in its scope. By analyzing existing meta-analyses rather than just individual studies, Singh et al. (2025) provided high-level evidence that physical exercise consistently outperforms many other interventions for cognitive enhancement. The effects weren't marginal—they were substantial enough to be clinically meaningful.

This is particularly important for understanding that exercise-induced cognitive improvements aren't flukes or anomalies; they're reliable, reproducible outcomes that appear across diverse populations and exercise protocols.

Study 2: How Fitness Shapes Your Brain's Electrical Activity

Study: Cortes-Ospina et al. (2025) Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Cortical Activation

While Singh et al. looked at behavioral outcomes (what you can do), Cortes-Ospina and colleagues peered into the brain's biology using electroencephalography (EEG) to measure resting-state cortical activation. Specifically, they examined how cardiorespiratory fitness relates to power spectrum density—essentially, the electrical patterns your brain produces at rest.

Higher cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with distinct patterns of cortical activation that correlate with better cognitive performance and more efficient neural function.

This study bridges the gap between what we observe behaviorally and what's happening at the neurological level. It shows that physical fitness literally changes how your brain operates at the cellular and electrical level. The more fit you are, the more efficiently your brain's neural networks communicate, even when you're not actively thinking hard.

This finding is crucial because resting-state brain activity is increasingly recognized as a marker of brain health and resilience against cognitive decline. Essentially, cardiorespiratory fitness creates a brain that's more "ready to go" and more efficient in its baseline operations.

Study 3: A Call to Action from Leading Neuroscientists

Study: Majumdar (2025) Editorial: Exercising Body & Brain

Vikram Majumdar's editorial in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience synthesizes the current state of knowledge about how physical exercise affects brain health. Rather than presenting original research, this editorial contextualizes recent findings and emphasizes the urgent need for exercise prescriptions to be integrated into brain health interventions.

The editorial argues that exercise should be considered a primary tool in cognitive health, alongside—and sometimes ahead of—pharmaceutical interventions.

Editorials from leading journals often signal paradigm shifts in scientific thinking. Majumdar's emphasis on the interconnection between body and brain health reflects a growing consensus that physical activity isn't supplementary—it's fundamental.

For the average person, this means that exercise deserves the same attention in your health routine that you'd give to medication. It's not just nice to do; it's essential to do if you want to maintain cognitive vitality as you age.

Study 4: The Mechanisms Behind Exercise's Brain Benefits

Study: Tari et al. (2025) Neuroprotective Mechanisms and Brain Aging

Tari and colleagues conducted a comprehensive review published in The Lancet examining the neuroprotective mechanisms through which exercise guards against brain aging and maintains brain health. This research identified specific biological pathways by which physical exercise protects neural tissue:

Neuroplasticity enhancement (the brain's ability to rewire and adapt)

Neuroinflammation reduction (decreasing harmful inflammation in the brain)

Neuroprotein production (increasing protective molecules like brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF)

Vascular health improvement (better blood flow to the brain)

Metabolic optimization (improved energy production in brain cells)

The research emphasizes that fitness level—not just exercise frequency—is crucial. People with higher aerobic fitness showed greater protection against age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases.

This is where the "why" becomes clear. Exercise works at the molecular level, triggering cascades of protective mechanisms. It's not magic; it's biology. When you exercise regularly enough to build cardiorespiratory fitness, your brain receives multiple protective signals simultaneously.

This explains why exercise interventions are often more effective than single-agent drug treatments—exercise simultaneously activates multiple protective pathways. It's like taking several medications at once, except it's one activity with no negative side effects.

Study 5: Understanding How Exercise Creates Cognitive Gains

Study: Li et al. (2025) Neural Correlates of Exercise-Induced Cognitive Gains

While Cortes-Ospina examined resting-state brain activity, Li and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to observe how physical exercise changes brain activation patterns during cognitive tasks. Their systematic review and meta-analysis focused specifically on the neural correlates—the brain mechanisms—underlying general cognitive gains from exercise.

The analysis revealed that physical exercise produces measurable changes in brain structure and functional connectivity:

Gray matter volume increases (the brain's processing centers grow)

White matter integrity improves (the brain's communication highways strengthen)

Functional connectivity between key brain regions enhances (better neural network communication)

Prefrontal cortex activation increases (strengthening the brain's executive control center)

This research provides the missing link between "exercise makes you feel sharper" and "exercise literally rewires your brain." fMRI studies show that when you exercise consistently, your brain physically changes—it grows in regions critical for thinking, planning, and memory.

The implications are profound: cognitive improvements from exercise aren't just psychological; they're grounded in observable, measurable changes to brain architecture. Your brain is literally becoming more capable.

Study 6: Fitness, Genetics, and Dementia Prevention

Study: Wang et al. (2025) Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Dementia Risk

One of the most compelling recent discoveries is that cardiorespiratory fitness can modify dementia risk even in people with high genetic predisposition for cognitive decline. Wang and colleagues examined a large community-based longitudinal study investigating how physical fitness interacts with genetic factors to influence dementia risk.

The findings were striking: even people with genes that increase dementia risk experienced substantial risk reduction when they maintained high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness. In other words, physical fitness acts as a powerful buffer against genetic vulnerability.

This means that your genes don't determine your destiny—your lifestyle does. People with unfortunate genetic circumstances could still protect themselves through regular exercise.

If you have a family history of Alzheimer's disease or cognitive decline, this research offers hope. While you can't change your genes, you can absolutely change your fitness level. The research suggests that aerobic fitness is one of the most powerful modifiable risk factors for dementia prevention.

This gives us a concrete, actionable strategy: if you're worried about cognitive decline or dementia risk, prioritize activities that build cardiorespiratory fitness like running, cycling, swimming, or brisk walking.

Study 7: Brain Age and Neurodegeneration in Cognitive Impairment

Study: Derboghossian et al. (2025) Fitness, Brain Age, and Neurodegeneration

Derboghossian and colleagues studied older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI)—a condition that often precedes Alzheimer's disease. They examined relationships among cardiorespiratory fitness, brain age (a measure of whether your brain looks younger or older than your chronological age), and markers of neurodegeneration.

The results showed that individuals with higher cardiorespiratory fitness had younger-looking brains and showed less evidence of neurodegeneration compared to their sedentary peers—even though they had the same diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

This study is particularly important because it shows that exercise benefits extend even to people already experiencing cognitive problems. If you've been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or have memory concerns, it's not too late to benefit from physical fitness.

The concept of brain age is revolutionary—it means your brain's biological age can be younger than your chronological age if you stay fit. Imagine being 70 years old but having a 60-year-old brain in terms of biological aging. That's what consistent exercise can achieve.

Synthesizing the Evidence: What All This Research Means

When you look at these seven research contributions together, a powerful narrative emerges:

Exercise is a comprehensive brain intervention. It improves your cognitive abilities (Singh et al., 2025), changes your brain's electrical patterns (Cortes-Ospina et al., 2025), activates neuroprotective mechanisms (Tari et al., 2025), restructures your brain architecture (Li et al., 2025), reduces your dementia risk regardless of genetics (Wang et al., 2025), and slows brain aging even in those already experiencing cognitive decline (Derboghossian et al., 2025).

The editorial perspective (Majumdar, 2025) ties it all together: exercise deserves to be recognized as a primary intervention for brain health, not a secondary or supplementary one.

How Exercise Improves Your Brain: The Mechanisms

Understanding why exercise helps your brain makes it easier to stay motivated. Here are the key mechanisms:

1. Increased Blood Flow and Oxygen Delivery

Exercise dramatically increases blood flow to your brain. More blood means more oxygen and nutrients reaching your neural tissue, supporting both cognitive function and neuroprotection.

2. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Production

BDNF is often called "fertilizer for the brain." Aerobic exercise is one of the most potent stimulators of BDNF, which supports neuroplasticity, memory formation, and cognitive resilience.

3. Reduced Neuroinflammation

Chronic low-grade inflammation in the brain contributes to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. Exercise suppresses this neuroinflammation, protecting your brain from harm.

4. Enhanced Neuroplasticity

Your brain maintains the ability to rewire itself throughout life—a property called neuroplasticity. Physical exercise enhances this capacity, making it easier to learn new skills and form new memories.

5. Optimized Metabolic Function

Brain cells are energy-hungry. Exercise improves mitochondrial function in brain cells, meaning they produce energy more efficiently.

6. Improved Vascular Health

Exercise strengthens blood vessel walls and promotes the growth of new blood vessels in the brain, ensuring robust cerebral blood flow.

Practical Implementation: How Much Exercise Do You Need?

You might be wondering: "Okay, so exercise is good for my brain—but how much do I need to do?"

While the research doesn't prescribe an exact amount universally, the evidence consistently points to these guidelines:

Aerobic Exercise

150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week (or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity) represents the sweet spot for cognitive benefits. This could be:

Brisk walking

Jogging or running

Cycling

Swimming

Tennis

Group fitness classes

Resistance Training

2-3 sessions per week of resistance or strength training provides additional cognitive benefits beyond aerobic exercise alone. The key is consistency over intensity.

Combined Approach

Research suggests that combining aerobic exercise with resistance training produces superior results for brain health compared to either alone.

The Fitness Factor

Remember Wang et al.'s (2025) findings: it's not just about exercise frequency—cardiorespiratory fitness level itself is protective. This means building up your fitness progressively matters.

FAQ: Your Questions Answered

Q: Is it ever too late to start exercising for brain benefits?

A: No. Derboghossian et al. (2025) showed that even older adults with diagnosed cognitive impairment benefit from fitness improvements. Whether you're 30 or 80, starting exercise can help your brain.

Q: Does the type of exercise matter?

A: Aerobic exercise that increases cardiorespiratory fitness appears most beneficial for cognitive outcomes. However, resistance training adds complementary benefits. The best exercise is the one you'll consistently do.

Q: How long until I notice cognitive improvements?

A: This varies, but many studies show measurable improvements within 8-12 weeks of consistent aerobic training. Structural brain changes may take longer—months to years—but functional improvements can appear relatively quickly.

Q: Can exercise reverse existing cognitive decline?

A: Derboghossian et al. (2025) suggest that exercise can slow neurodegeneration and improve cognitive function even in those with mild cognitive impairment. While it may not fully reverse significant decline, it can meaningfully improve outcomes.

Q: I'm very busy—can short workouts help?

A: Even modest increases in physical activity provide benefits. While 150 minutes weekly is optimal, something is always better than nothing. Consistency matters more than perfection.

Q: What if I have joint problems or other physical limitations?

A: Work with a physical therapist or doctor to find modified aerobic activities you can perform. Swimming, water aerobics, and stationary cycling are gentler on joints while building cardiorespiratory fitness.

Q: Does social exercise (like group fitness) offer additional benefits?

A: While not specifically examined in these studies, the cognitive engagement and social interaction components of group exercise likely add additional benefits beyond the physical activity alone.

Q: Can diet enhance exercise's brain benefits?

A: While these studies focus on exercise, research elsewhere suggests that combining exercise with a brain-healthy diet (Mediterranean or MIND diet) optimizes cognitive outcomes.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Remember

Exercise is a powerful cognitive enhancer: The evidence from meta-analyses confirms that physical activity improves memory, thinking speed, and executive function in both healthy individuals and those with cognitive decline.

Fitness level matters: It's not just about moving—building cardiorespiratory fitness appears to be the key mechanism through which exercise protects your brain.

Exercise works through multiple mechanisms: From increasing BDNF to reducing neuroinflammation to restructuring your brain architecture, exercise influences brain health at every biological level.

Genetics don't determine your fate: Even people with genetic predisposition to dementia can substantially reduce their risk through maintaining high fitness levels.

It's never too late: Whether you're 30 or 80, with or without cognitive concerns, exercise can improve your brain's structure and function.

Consistency beats intensity: Regular moderate-intensity exercise produces better results than sporadic intense workouts.

Combination training is superior: Aerobic exercise combined with resistance training outperforms either approach alone.

The Bottom Line: Your Brain's Greatest Asset

The research is unequivocal: exercise is one of the most powerful tools available for protecting and enhancing your brain. It's not a supplement to other health interventions—it's fundamental.

Whether your goal is to enhance cognitive performance now, prevent cognitive decline in the future, or slow neurodegeneration if you're already experiencing it, the solution is the same: move your body consistently.

The good news? Unlike many health interventions, this one is free, accessible to most people, and comes with countless benefits beyond brain health. Every time you exercise, you're not just improving your body—you're literally reshaping your brain in ways that enhance your thinking, protect your memory, and fortify your mental resilience.

Call to Action

Start small: If you're currently inactive, begin with just 10-15 minutes of walking daily and gradually build up.

Find your activity: Choose something you enjoy—it could be walking, dancing, cycling, swimming, or team sports. Consistency requires doing something you actually like.

Build cardiorespiratory fitness: Aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, combined with 2-3 resistance training sessions.

Make it social: Exercise with friends or a group—it adds enjoyment and accountability.

Consult your doctor: If you have health concerns or are beginning a new exercise program, get medical clearance first.

Be patient: Brain changes take time. Trust the process and focus on consistency over perfection.

Track your progress: Notice improvements in focus, memory, mood, and overall mental clarity—these are signs your brain is being transformed.

Your brain is waiting for you to move. Start today.

Author’s Note

As a physician, researcher, and educator working at the intersection of metabolism, internal medicine, and preventive health, my goal in writing this article is to bridge the gap between scientific evidence and practical application. Over the past two decades, the fields of neuroscience and metabolic medicine have converged to reveal a powerful truth: movement is one of the most effective interventions we have to protect the brain, prevent cognitive decline, and enhance long-term health.

The insights shared here are not theoretical summaries—they reflect a growing body of peer-reviewed research, including randomized trials, fMRI analyses, longitudinal cohort studies, and mechanistic investigations into neuroinflammation, BDNF pathways, mitochondrial function, and neuroplasticity. These findings are deeply relevant not only to aging populations but also to individuals managing metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, obesity, and type 2 diabetes—conditions I have written extensively about in chapters across my books.

My hope is that this article empowers you with both clarity and confidence: clarity about how exercise transforms the brain, and confidence to apply these principles consistently in daily life. Whether you are a clinician, a student, a researcher, or a health-conscious reader, the message is the same—your brain thrives on movement, and it is never too early or too late to start.

If this topic resonates with you, I encourage you to explore my upcoming text series on strength training, metabolic health, and diabetes, where these concepts are explored in greater scientific depth and practical detail.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting any new exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

Fasted vs. Fed Exercise: Does Training on an Empty Stomach Really Burn More Fat? | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise vs. Diet Alone: Which is Best for Body Composition? | DR T S DIDWAL

Movement Snacks: How VILPA Delivers Max Health Benefits in Minutes | DR T S DIDWAL

Anabolic Resistance: Why Muscles Age—and How to Restore Their Growth Response | DR T S DIDWAL

Breakthrough Research: Leptin Reduction is Required for Sustained Weight Loss | DR T S DIDWAL

The Psychology of Strength Training: Building Resilience Beyond the Gym | DR T S DIDWAL

HIIT Benefits: Evidence for Weight Loss, Heart Health, & Mental Well-Being | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Cortes-Ospina, M., Baumgartner, N. W., Nagy, C., Noh, K., Wang, C. H., & Kao, S. C. (2025). The relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and resting-state cortical activation: An EEG study on power spectrum density. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 213, 112600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2025.112600

Derboghossian, G., Pituch, K., Anthony, M., Salisbury, D., Lin, F. V., & Yu, F. (2025). Relationships among cardiorespiratory fitness, brain age, and neurodegeneration in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 105(3), 945–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1387287725133361

Li, G., Xia, H., Teng, G., & Chen, A. (2025). The neural correlates of physical exercise-induced general cognitive gains: A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 169, 106008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106008

Majumdar, V. (2025). Editorial: Exercising body & brain: The effects of physical exercise on brain health. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 19, Article 1753714. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2025.1753714

Singh, B., Bennett, H., Miatke, A., Dumuid, D., Curtis, R., Ferguson, T., Brinsley, J., Szeto, K., Petersen, J. M., Gough, C., Eglitis, E., Simpson, C. E., Ekegren, C. L., Smith, A. E., Erickson, K. I., & Maher, C. (2025). Effectiveness of exercise for improving cognition, memory and executive function: A systematic umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 59(12), 866–876. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2024-108589

Tari, A. R., Walker, T. L., Huuha, A. M., Sando, S. B., & Wisloff, U. (2025). Neuroprotective mechanisms of exercise and the importance of fitness for healthy brain ageing. The Lancet, 405(10484), 1093–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)00184-9

Wang, S., Xu, L., Yang, W., Wang, J., Dove, A., Qi, X., & Xu, W. (2025). Association of cardiorespiratory fitness with dementia risk across different levels of genetic predisposition: A large community-based longitudinal study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 59(3), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-108048