Anabolic Resistance: Why Muscles Age—and How to Restore Their Growth Response

Why do muscles age? Learn how anabolic resistance works—and how science-backed exercise and protein strategies can help rebuild strength as you age

AGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

12/26/202513 min read

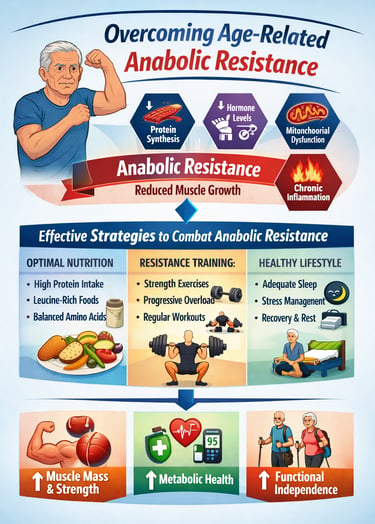

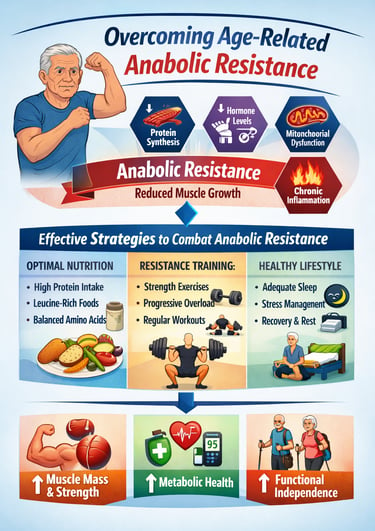

If you’ve ever wondered why the same workouts and meals that once built muscle effortlessly now seem to deliver smaller results, science has an answer. As we age, skeletal muscle becomes less responsive to key growth signals from protein intake and resistance exercise—a phenomenon known as age-related anabolic resistance. This biological shift plays a central role in sarcopenia, the gradual loss of muscle mass and strength that accelerates after midlife and increases the risk of frailty, falls, insulin resistance, and loss of independence (Aragon et al., 2023).

Importantly, anabolic resistance is not a failure of willpower, nor is it an inevitable consequence of aging. At the cellular level, aging muscle shows reduced sensitivity to essential amino acids, impaired activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway, mitochondrial inefficiency, and the suppressive effects of chronic low-grade inflammation—often referred to as inflammaging (Deane et al., 2024). Together, these changes blunt muscle protein synthesis, even when nutrition and exercise appear “adequate” by younger-adult standards.

The encouraging news is that modern research tells a more hopeful story. Large reviews and controlled trials demonstrate that targeted nutrition strategies, higher and better-distributed protein intake, and progressive resistance training can meaningfully restore anabolic responsiveness in older adults (Pérez-Castillo et al., 2025; Korzepa et al., 2025). In other words, muscle aging is modifiable. With the right approach, strength, function, and metabolic health remain well within reach—at any age.

Clinical pearls :

1. The "Volume Knob" Concept

Think of your muscle’s "growth receptors" as a radio. In your 20s, the volume is sensitive; a little protein or a light workout is a clear signal. As we age, the "volume" naturally turns down. Anabolic resistance is essentially "muffled" signaling. To hear the signal and build muscle, you don't necessarily need a new radio—you just need to turn the volume up by eating more protein per meal and lifting heavier weights than you think you need.

2. The "Leucine Trigger"

Not all protein is created equal when it comes to "waking up" aging muscles. Leucine is a specific amino acid that acts like a biological "on switch" for muscle repair. For older adults, hitting a "threshold" of about 3–4g of leucine in a single meal is often what’s required to overcome resistance. This is why a small snack doesn't cut it; you need a robust "dose" of protein to reach that threshold and trigger the growth machinery.

3. The 24-Hour Muscle Window

Many people eat most of their protein at dinner, but your muscles don't have a "storage tank" for protein like they do for fat or carbs. If you eat 80g of protein at 7:00 PM but only 5g at breakfast, your muscles spend most of the day in a "breakdown" state. Spreading protein across 4–5 even doses ensures the "build" signal is active all day long, preventing the slow leak of muscle mass.

4. Muscle is "Metabolic Armor"

Muscle isn't just for looking fit; it is your body's largest "sink" for blood sugar. Age-related muscle loss is often the silent driver behind Type 2 diabetes and metabolic slowing. By treating resistance training as "Metabolic Armor," you aren't just building strength; you are improving how your body processes every meal you eat and protecting your internal organs from inflammation.

5. Synergy, Not Substitution

Nutrition and exercise are not "either/or" choices—they are a 1+1=3 equation. Research shows that eating protein without exercise is inefficient, and exercising without protein is exhausting. However, exercise actually "sensitizes" the muscle to the protein you eat for up to 24–48 hours afterward. This means your workout today actually makes your lunch tomorrow more effective at building muscle.

Age-Related Anabolic Resistance: Can We Prevent Muscle Loss as We Age?

What Is Anabolic Resistance?

Anabolic resistance refers to the blunted or diminished muscle protein synthesis response that occurs when older adults consume protein or engage in resistance training. Essentially, it means that the same stimulus that would trigger significant muscle growth in a younger person produces a smaller response in an older adult.

This phenomenon becomes increasingly relevant as we age because sarcopenia—the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength—directly impacts quality of life, independence, and metabolic health. Understanding the mechanisms behind anabolic resistance is the first step toward preventing or reversing it.

Key Research Insight

Aragon et al. (2023) posed a critical question that captures the current scientific thinking: Is age-related muscle anabolic resistance inevitable or preventable? Their comprehensive review examined the evidence and concluded that while age-related changes do occur, the severity and impact are not predetermined. Rather, multiple therapeutic strategies and lifestyle factors can substantially influence outcomes.

Understanding the Mechanisms: Why Muscles Respond Less to Stimuli

Before we discuss solutions, it's important to understand what's actually happening at the cellular level. Age-related anabolic resistance doesn't stem from a single cause; instead, it results from multiple interconnected factors.

Critical Variables in Aging Muscles

Deane et al. (2024) investigated the critical variables regulating age-related anabolic responses to protein nutrition in skeletal muscle. Their research highlighted several key physiological mechanisms that change with age:

Reduced sensitivity to amino acids: Aging muscles show diminished responsiveness to essential amino acids, particularly leucine, which normally serves as a trigger for muscle protein synthesis

Altered signaling pathways: The mTORC1 pathway and related growth-signaling mechanisms function less efficiently in older adults

Mitochondrial dysfunction: Aging muscles have compromised mitochondrial health, reducing their capacity to produce the energy needed for protein synthesis

Increased inflammation: Chronic, low-grade inflammation in aging muscles suppresses anabolic signals

The research emphasized that understanding these variables is essential for developing targeted interventions to restore muscle anabolic capacity. Multiple points along the pathway to muscle protein synthesis can be optimized.

The Systems-Level Perspective

Recent modeling research has taken an innovative approach to understanding sarcopenia. A 2025 systems modeling study examined how various factors interact and compound over time. This research demonstrated that anabolic resistance isn't simply the result of one broken mechanism, but rather emerges from multiple factors working together:

Nutritional inadequacies interacting with reduced muscle sensitivity

Hormonal changes (declining testosterone and growth hormone) compounding the problem

Reduced physical activity amplifying other risk factors

Poor metabolic flexibility limiting the body's adaptation capacity

The key takeaway: because age-related anabolic resistance is multifactorial, interventions targeting multiple pathways simultaneously prove most effective.

The Role of Nutrition in Overcoming Anabolic Resistance

Protein Intake and Amino Acid Profiles

One of the most researched and actionable interventions for anabolic resistance involves optimizing protein intake. While the standard recommendation of 0.8g of protein per kilogram of body weight works fine for younger adults, older adults typically benefit from significantly higher intake.

Pérez-Castillo et al. (2025) conducted a comprehensive review of nutritional and exercise strategies for overcoming anabolic resistance. Their work identified several crucial nutritional strategies:

Protein quantity and distribution: Research increasingly supports consuming 1.2-2.0g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily for older adults, distributed across 4-5 meals. This spacing appears more effective than consuming large amounts in one or two sittings, as it consistently stimulates muscle protein synthesis throughout the day.

Leucine enrichment: Leucine, a branched-chain amino acid, acts as a metabolic trigger for the mTORC1 pathway. Higher leucine concentrations can partially overcome the diminished sensitivity older muscles show to standard amino acid ratios.

Essential amino acid composition: Proteins containing all nine essential amino acids in balanced proportions prove superior for stimulating muscle protein synthesis compared to incomplete protein sources.

Of particular note, older adults who maintain consistent exercise habits show better anabolic responsiveness to protein, suggesting that chronic exercise training actually helps preserve or restore anabolic sensitivity.

Practical Protein Recommendations

Recent research tested whether protein source matters for resistance training outcomes in middle-aged and older adults. The findings provided encouraging news for those following various dietary patterns.

The research found that myofibrillar protein synthesis—the type of protein synthesis that builds the contractile machinery of muscle—increased significantly following resistance training in older adults regardless of whether they consumed animal-based proteins, plant-based proteins, or mixed sources. This suggests that older adults can successfully build muscle on various protein sources, as long as total intake is adequate and combined with appropriate training.

Key takeaway: What matters most isn't the specific protein source but ensuring sufficient total protein intake and engaging in resistance training. This finding is particularly important for vegetarians, vegans, and those with dietary restrictions.

Dietary sources of Leucine

To overcome age-related anabolic resistance, current research suggests targeting 2.5g to 3g of leucine per meal. This "leucine trigger" is the biological threshold required to restart muscle protein synthesis in older adults.

Below is a brief note on the most effective food sources categorized by their "leucine density."

High-Leucine Animal Sources

Animal proteins are naturally high in leucine and more easily absorbed by the body. They typically provide the "trigger" dose in a standard 4–6 oz serving.

Whey Protein Isolate: The gold standard for leucine. One scoop (~25g of protein) contains roughly 2.5g–3.0g of leucine, making it the most efficient way to hit the threshold.

Chicken & Turkey: A 6 oz (170g) breast provides approximately 3.5g–4.0g of leucine.

Meat(Lean cuts): 6 oz of top sirloin or skirt steak offers about 3.5g–4.5g of leucine, along with bioavailable iron and zinc.

Fish (Salmon/Tuna): A 6 oz fillet of salmon or bluefin tuna contains about 3.0g–4.0g of leucine.

Dairy: Greek yogurt and cottage cheese are powerhouses. One cup of low-fat cottage cheese provides about 2.8g–3.0g of leucine.

High-Leucine Plant Sources

While plant sources often contain less leucine per gram than meat, they can still hit the "growth trigger" if you consume larger portions or use protein isolates.

Soy (Tofu/Tempeh): Firm tofu is one of the best plant sources. One cup (approx. 250g) of firm tofu provides about 3.0g–3.5g of leucine.

Pumpkin Seeds (Pepitas): A very dense source; a 100g serving contains about 2.4g of leucine.

Lentils & Navy Beans: These are moderate sources. You typically need about 2 cups of cooked lentils to reach the 2.5g leucine mark.

Pea Protein Powder: A high-quality plant isolate. One scoop (~25g of protein) usually provides about 2.0g–2.2g of leucine.

Pro Tip: If you are eating a meal lower in protein (like a salad or a bowl of oatmeal), consider "spiking" it with a small amount of a leucine-rich food (like an egg or a sprinkle of pumpkin seeds) to reach that growth-trigger threshold.

Exercise Strategies: The Powerful Tool Against Anabolic Resistance

Anabolic Signals and Muscle Hypertrophy

While nutrition is crucial, exercise—particularly resistance training—remains the most powerful stimulus for overcoming anabolic resistance. Recent research examining anabolic signals and muscle hypertrophy in sports medicine contexts provided detailed insights into how growth mechanisms function.

Resistance training triggers multiple anabolic signals simultaneously:

Mechanical tension: Heavy loads create mechanical stress on muscle fibers, activating growth pathways

Muscle damage: Controlled damage from resistance exercise triggers repair and adaptation responses

Metabolic stress: The "pump" and accumulated metabolites create additional growth stimuli

Hormonal responses: Resistance training elevates testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)

For aging athletes and regular exercisers, maintaining adequate anabolic signals through consistent strength training becomes increasingly important as age-related hormonal changes occur naturally.

Optimal Training Characteristics for Older Adults

The research consensus suggests several evidence-based training principles for maximizing anabolic responses in older populations:

Progressive overload: Gradually increasing weight, volume, or intensity remains non-negotiable. Muscles need increasing challenges to continue adapting.

Adequate volume: Multiple sets (3-4 per exercise) targeting each muscle group appear necessary to achieve hypertrophy responses in older adults, contrasting with some research in younger individuals showing single-set effectiveness.

Frequency and distribution: Training each muscle group 2-3 times weekly distributes the anabolic stimulus throughout the week, taking advantage of the aging muscle's potentially prolonged recovery needs.

Recovery emphasis: While older adults need more recovery time, evidence suggests that total weekly anabolic signals matter most. Proper sleep (7-9 hours), stress management, and nutrition during recovery windows are paramount.

Integrating Nutrition and Exercise: The Synergistic Approach

The most exciting finding across these studies is that nutritional interventions and exercise strategies work synergistically. Comprehensive reviews highlight this critical interaction: protein intake stimulates muscle protein synthesis most effectively when combined with resistance training. The two are not independent variables but rather multiplicative factors in overcoming anabolic resistance.

Practical Application

Consider this scenario: An older adult consumes 1.6g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, distributing it across five meals. Without resistance training, this protein intake produces modest muscle protein synthesis. However, when combined with consistent progressive resistance training, the same protein intake produces substantially greater muscle hypertrophy and strength gains.

Conversely, someone performing excellent strength training without adequate protein intake limits their results significantly. Both factors must be optimized.

The Role of Insulin Sensitivity in Muscle Building

While testosterone and growth hormone are the "architects" of muscle, insulin is the "gatekeeper."

In healthy muscle tissue, insulin acts as a powerful anabolic signal that shuttles amino acids into cells to begin the repair process. However, as we age, muscles can become insulin resistant. When this happens, even if you eat high-quality protein, the "gate" remains partially closed, preventing those nutrients from entering the muscle fibers efficiently.

Why this matters for Anabolic Resistance:

Nutrient Partitioning: Insulin resistance shifts the body’s priority; instead of using nutrients for muscle repair, the body is more likely to store them as fat.

The Inflammation Loop: Poor insulin sensitivity increases systemic inflammation, which further blunts the mTORC1 growth pathway.

The Solution: Resistance training is the most effective way to "resensitize" the muscle to insulin. A single bout of exercise can increase glucose and amino acid uptake for up to 48 hours, effectively propping the gate open for your recovery meals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is it too late to start building muscle if I'm in my 60s or 70s?

A: Absolutely not. Research across these studies consistently shows that older adults, even those beginning resistance training later in life, respond with meaningful muscle hypertrophy and strength gains when nutrition and training are optimized. The magnitude of response may be somewhat smaller than in younger individuals, but the improvement trajectory can be substantial.

Q: How much protein do I really need?

A: Current evidence suggests 1.2-2.0g of protein per kilogram of body weight daily for older adults engaging in resistance training. A 70kg (154-lb) person would target 84-140g daily. If this seems high, remember it's distributed across all meals—roughly 20-30g per meal for four meals works well.

Q: Do I need supplements, or can I get enough protein from food?

A: Whole foods can provide adequate protein for most people. However, some individuals find protein supplements convenient for ensuring consistent intake, particularly after training or between meals. The Korzepa et al. (2025) study found no difference in muscle protein synthesis responses based on protein source, suggesting that whether you choose chicken, fish, legumes, tofu, or powder, what matters is total intake.

Q: How often should I train if I'm older?

A: Training each major muscle group 2-3 times weekly appears optimal. This might mean three full-body sessions weekly, or an upper/lower split performed twice weekly. The key is consistency and progressive challenge, not excessive frequency.

Q: What if I have joint problems or mobility limitations?

A: Modified resistance training using machines, lighter weights, different angles, or isometric holds can effectively stimulate muscle protein synthesis even with physical limitations. Consult a physical therapist or qualified trainer to design a program accommodating your specific needs.

Q: Can I overcome anabolic resistance just with nutrition, without exercise?

A: Unfortunately, no. While nutrition provides the building blocks and supports the metabolic environment for growth, resistance training provides the actual stimulus that triggers muscle protein synthesis. Both are necessary.

Q: How long before I see results?

A: Measurable changes in muscle strength typically appear within 2-3 weeks of consistent training, even if muscle size gains take 6-8 weeks to become visually apparent. Metabolic improvements and functional gains often arrive even sooner.

Moving Forward: Your Action Plan

Based on the comprehensive research reviewed here, here's a practical framework for overcoming age-related anabolic resistance:

Week 1-2: Assessment and Planning

Calculate your current protein intake (aim for at least 1.2g per kg body weight)

Evaluate your current training frequency and volume

Establish baseline strength measurements in 3-4 major lifts

Schedule any necessary medical clearance for training

Week 3-4: Implementation

Restructure meals to include adequate protein at each eating occasion

Begin or modify resistance training to include progressive overload

Establish a consistent sleep schedule (7-9 hours nightly)

Track training volume and protein intake

Month 2 Onward: Progression and Optimization

Gradually increase training volume and intensity as tolerated

Fine-tune protein timing and amount based on training and body composition changes

Reassess progress monthly; adjust variables based on response

Consider consulting a sports dietitian or strength coach for personalized optimization

Key Takeaways

Age-related anabolic resistance is preventable and partially reversible through targeted interventions (Aragon et al., 2023)

Multiple mechanisms contribute to reduced anabolic capacity in aging muscles, requiring multifaceted solutions (Deane et al., 2024; Exploring the multifactorial causes and therapeutic strategies for anabolic resistance in sarcopenia, 2025)

Older adults require higher protein intake (1.2-2.0g/kg body weight) distributed across multiple meals throughout the day (Pérez-Castillo et al., 2025)

Protein source matters less than total intake and training stimulus for building muscle in older age (Korzepa et al., 2025)

Resistance training is the most powerful anabolic stimulus, triggering multiple growth pathways even in aging muscles (Behringer et al., 2025)

Combined nutrition and exercise strategies produce synergistic effects far exceeding either intervention alone

Life-long exercisers maintain superior anabolic responsiveness, suggesting that consistent activity throughout life provides protective benefits (Pérez-Castillo et al., 2025)

Multifactorial interventions addressing nutrition, exercise, sleep, and stress management optimize outcomes (Exploring the multifactorial causes and therapeutic strategies for anabolic resistance in sarcopenia, 2025)

The Bottom Line

Age-related anabolic resistance is not an inevitable consequence of aging. The converging evidence from Aragon et al. (2023), Pérez-Castillo et al. (2025), Behringer et al. (2025), Deane et al. (2024), Korzepa et al. (2025), and recent systems modeling research (Exploring the multifactorial causes and therapeutic strategies for anabolic resistance in sarcopenia, 2025) demonstrates clearly that older adults can build and maintain substantial muscle mass through optimized nutritional strategies, progressive resistance training, and holistic lifestyle practices.

The research isn't just academically interesting—it's practically actionable. Whether you're 50, 70, or 90, your muscles retain the capacity to respond to appropriate stimuli. The question isn't whether you can build muscle as you age, but whether you'll apply the evidence-based strategies that make it possible.

Your strongest self isn't behind you—it's achievable right now with the right approach.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers before starting any new treatment program, especially if you have existing health conditions or take medications.

Related Articles

Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia: The Critical Connection | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Prevent Sarcopenia: Fight Age-Related Muscle Loss and Stay Strong | DR T S DIDWAL

Who Gets Sarcopenia? Key Risk Factors & High-Risk Groups Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Exercises for Sarcopenia: Strength Training Guide for Older Adults | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Supplements for Sarcopenia: Vitamin D, Creatine, and HMB Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Aragon, A. A., Tipton, K. D., & Schoenfeld, B. J. (2023). Age-related muscle anabolic resistance: inevitable or preventable? Nutrition Reviews, 81(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac062

Behringer, M., Heinrich, C., & Franz, A. (2025). Anabolic signals and muscle hypertrophy – Significance for strength training in sports medicine. Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 41(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthtr.2025.01.002

Deane, C. S., Cox, J., & Atherton, P. J. (2024). Critical variables regulating age-related anabolic responses to protein nutrition in skeletal muscle. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1419229. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1419229

Exploring the multifactorial causes and therapeutic strategies for anabolic resistance in sarcopenia: A systems modeling study. (2025). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.09.12.675977v1

Korzepa, M., Quinlan, J. I., Marshall, R. N., Rogers, L. M., Belfield, A. E., Elhassan, Y. S., Lawson, A., Ayre, C., Senden, J. M., Goessens, J. P. B., Glover, E. I., Wallis, G. A., van Loon, L. J. C., & Breen, L. (2025). Resistance training increases myofibrillar protein synthesis in middle-to-older aged adults consuming a typical diet with no influence of protein source: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2025.04.019

Pérez-Castillo, Í. M., Rueda, R., Pereira, S. L., Bouzamondo, H., López-Chicharro, J., Segura-Ortiz, F., & Atherton, P. J. (2025). Age-related anabolic resistance: Nutritional and exercise strategies, and potential relevance to life-long exercisers. Nutrients, 17(22), 3503. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223503