Cellular Senescence: Why Your Cells Age and What It Means for Your Health

What is cellular senescence? Learn how aging cells affect your heart and brain, and discover emerging treatments like senolytics to improve your healthspan.

AGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/18/202611 min read

Why do our bodies change so dramatically as we age? Why does our skin wrinkle, our metabolism slow, our immunity weaken, and our risk of chronic diseases rise with every passing decade? For years, scientists believed aging was simply a natural consequence of time—a passive, unavoidable decline. But groundbreaking research over the past decade reveals something far more intriguing: aging is driven by specific biological processes that can be measured, modified, and potentially slowed down (Tenchov et al., 2024).

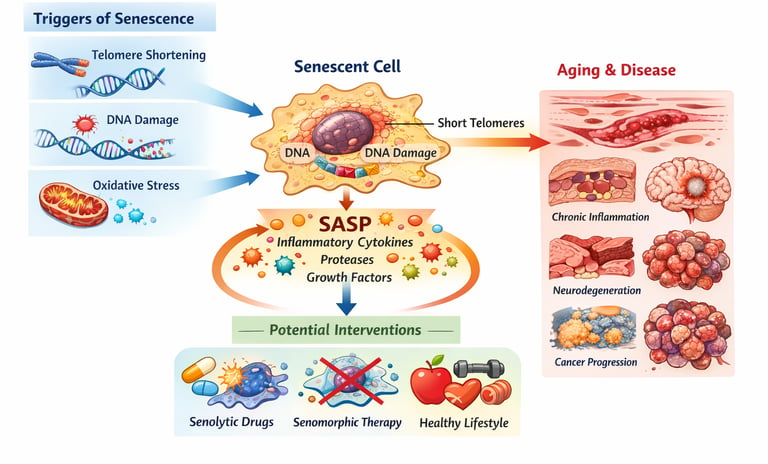

At the heart of this discovery is cellular senescence, a process in which cells stop dividing and enter a state of permanent arrest. Instead of dying, these dysfunctional cells linger in our tissues, releasing inflammatory molecules that damage surrounding cells and accelerate biological aging (Ajoolabady et al., 2025). These “zombie cells” accumulate in multiple organs over time, contributing to major age-related diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, neurodegeneration, cancer, and immune decline (Yamauchi & Takahashi, 2025).

Even more compelling, recent findings show that targeting senescent cells—either by eliminating them or suppressing their harmful secretions—may improve healthspan and slow disease progression (He et al., 2026). In other words, aging is no longer seen as inevitable. It is becoming treatable.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Zombie Cell" Effect

Think of senescent cells not as "dead" cells, but as "zombie cells." While they have stopped dividing, they refuse to die. Instead, they linger and "shout" inflammatory signals at their neighbors. This explains why aging isn't just about losing cells; it’s about the toxic environment created by the ones that stay behind too long.

2. The Hayflick Limit: Your Biological Odometer

Every cell has a built-in odometer called telomeres. Every time a cell divides to repair your body, the "cap" on the end of the DNA gets shorter. Once it hits a certain point (the Hayflick Limit), the cell pulls the emergency brake and enters senescence. We can’t stop the odometer, but lifestyle choices can prevent "engine overheating" that makes the miles add up faster.

3. SASP: Inflammation is Contagious

One of the most important clinical findings is the SASP (Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype). Senescent cells secrete a "chemical soup" of inflammatory markers. This means that a few senescent cells in a joint or a blood vessel can actually "corrupt" the healthy cells around them, spreading inflammation like a biological wildfire.

4. The Double-Edged Sword of Cancer Defense

In your youth, cellular senescence is actually your friend—it is a powerful anti-cancer mechanism. When a cell becomes mutated or damaged, senescence force-retires that cell so it can’t turn into a tumor. The problem only arises in later life when our immune system (specifically those CD8+ T cells mentioned in the 2026 study) becomes too tired to "trash collect" these retired cells.

5. Moving from Lifespan to "Healthspan"

The goal of studying senolytics (drugs that clear zombie cells) isn't just to make us live longer, but to extend our healthspan. By clearing the "cellular clutter," we aim to keep the body's tissues functional and pain-free for a larger percentage of our lives. Current research suggests that managing blood sugar and regular movement are the best ways we currently have to support our body’s natural ability to manage these aging cells.

Cellular Senescence: Understanding the Hallmarks and Mechanisms Behind Aging and Disease

Cellular senescence refers to a state where cells permanently stop dividing but remain metabolically active and alive. Unlike cell death, where cells are destroyed and removed, senescent cells linger in our tissues, accumulating over time and potentially causing harm.

When cells become senescent, they undergo several characteristic changes:

Loss of proliferative capacity: Cells can no longer divide and replicate

Metabolic changes: The cell's ability to use energy shifts dramatically

Altered gene expression: Different genes turn on and off, changing what proteins the cell produces

Increased stress signals: The cell becomes metabolically stressed and dysfunctional

This process occurs naturally as we age, but it also happens prematurely in response to various stressors like DNA damage, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

The Four Cornerstone Studies: What Recent Research Reveals

Study 1: Cellular Senescence Hallmarks and Mechanisms (2025)

Ajoolabady et al. (2025) provide a comprehensive examination of the hallmarks of cellular senescence and their role in both normal aging and disease progression. This landmark study identifies the key characteristics that define senescent cells and explores how these changes contribute to age-related pathology.

Key Takeaways:

Cellular senescence is characterized by specific molecular hallmarks that distinguish senescent cells from normal aging cells

These hallmarks include telomere shortening, DNA damage, and altered gene expression patterns

The study emphasizes that senescence mechanisms vary depending on the type of cell and the triggering stimulus

Understanding these hallmarks of cellular senescence is crucial for developing targeted interventions

The research by Ajoolabady and colleagues highlights how senescent cells accumulate in various tissues and how this accumulation correlates with age-related diseases like cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer's, and type 2 diabetes.

Study 2: Aging Hallmarks and Age-Related Diseases Landscape (2024)

Tenchov et al. (2024) take a broader perspective, examining the relationship between the hallmarks of aging and age-related disease progression. Their landscape analysis identifies how various biological processes interact to drive aging and increase disease susceptibility.

Key Takeaways:

The study identifies nine hallmarks of aging, with cellular senescence being one of the most significant

Age-related diseases including cancer, neurodegeneration, and metabolic disorders all share common aging mechanisms

The research demonstrates that aging is not a single process but rather a complex interplay of interconnected biological pathways

Understanding these interconnections could lead to more effective prevention strategies

Tenchov's work emphasizes that many of the biological processes driving cellular aging are modifiable, suggesting that lifestyle interventions and targeted therapies could slow or even reverse age-related decline.

Study 3: Cellular Senescence, Cancer, and Aging Connection (2025)

Yamauchi and Takahashi (2025) focus specifically on how cellular senescence relates to both cancer development and the aging process. Their research in The Journal of Biochemistry reveals the double-edged nature of senescent cells.

Key Takeaways:

Senescent cells can paradoxically both prevent and promote cancer development

Early senescence acts as a tumor-suppression mechanism, preventing cancer cell growth

However, accumulated senescent cells in aging tissues can create an environment that promotes cancer through senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)

Understanding this paradox is critical for developing cancer prevention and treatment strategies

The study emphasizes the complexity of targeting senescence therapeutically

This research highlights why simply eliminating all senescent cells might not be the solution—we need to understand when senescence is protective and when it becomes harmful.

Study 4: CD8+ T Cell Aging and Disease (2026)

He et al. (2026) bring a specialized focus to immune cell senescence, examining how CD8+ T cells age and how this contributes to age-related immune dysfunction and disease susceptibility.

Key Takeaways:

CD8+ T cells are critical immune cells that become dysfunctional with age

T cell senescence impairs the immune system's ability to fight infections and cancer

The study identifies specific molecular markers of T cell aging that could be monitored therapeutically

Age-related immune dysfunction increases susceptibility to infections, cancer, and autoimmune disease

Targeting T cell senescence could potentially restore immune function in older adults

This research is particularly important because it reveals how aging affects our ability to defend ourselves against disease at the cellular level.

Understanding the Mechanisms: How Cells Become Senescent

The Telomere Connection

One of the most well-established mechanisms of cellular senescence involves telomeres—the protective caps at the ends of our chromosomes. Each time a cell divides, telomeres shorten slightly. After 50-70 divisions (known as the Hayflick limit), telomeres become critically short, signaling the cell to stop dividing.

This is the cell's built-in aging clock. Once telomeres reach a critical length, cells enter senescence to prevent the risk of becoming cancerous

.

DNA Damage and Stress Response

DNA damage from various sources—including UV radiation, environmental toxins, and normal metabolic byproducts—also triggers cellular senescence. When cells detect unrepairable DNA damage, they activate protective mechanisms that prevent further division, essentially locking the cell in a senescent state.

This is a safety mechanism, but accumulated DNA damage and the resulting senescent cells can drive aging and disease.

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Oxidative stress occurs when cells produce too many free radicals—reactive molecules that damage cellular components. As we age, our cells become less efficient at managing oxidative stress, leading to increased mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mitochondria are the powerhouses of our cells, and when they malfunction, cells struggle to maintain normal operations, eventually triggering senescence.

The SASP Factor: Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype

One of the most damaging aspects of cellular senescence is that senescent cells don't just sit quietly—they actively secrete inflammatory molecules. This phenomenon is called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

SASP molecules include:

Inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α

Growth factors that can promote tumor growth

Extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes that damage surrounding tissues

This is why accumulated senescent cells are so problematic—they create a toxic, inflammatory environment that damages nearby healthy cells and accelerates aging.

The Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence: A Complete Overview

Recent research has identified specific hallmarks of cellular senescence that researchers use to identify and study senescent cells:

Permanent Cell Cycle Arrest: Senescent cells cannot divide, marked by high levels of p16 and p21 proteins

Morphological Changes: Senescent cells become enlarged and develop an irregular shape

Altered Gene Expression: Changes in which genes are active, particularly increased expression of p16 and p21

Increased Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase: A enzyme activity that serves as a reliable marker of senescence

Increased Reactive Oxygen Species: Elevated ROS levels indicating oxidative stress

DNA Damage Markers: Presence of γH2AX foci indicating DNA breaks

SASP Activation: Secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules and growth factors

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Impaired energy production and increased mitochondrial stress signals

Understanding these markers helps researchers identify senescent cells in tissues and assess the effectiveness of anti-senescence treatments.

Cellular Senescence and Age-Related Diseases: The Connection

Cardiovascular Disease

Senescent cells accumulate in blood vessels, promoting atherosclerosis and increasing the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The SASP from these cells drives chronic inflammation in the vasculature.

Neurodegeneration

In the brain, cellular senescence contributes to neuroinflammation and the progression of diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Senescent cells in the brain secrete toxic molecules that damage neurons.

Type 2 Diabetes

Pancreatic cells that produce insulin become senescent, reducing insulin production and contributing to metabolic dysfunction.

Cancer

While early senescence prevents cancer, chronic accumulation of senescent cells can paradoxically promote cancer development through SASP signaling and altered tissue microenvironments.

Immune Dysfunction

As described in the research on CD8+ T cell aging, senescence of immune cells reduces our ability to fight infections and cancer.

The Research Frontier: New Discoveries and Future Directions

The four studies we've examined reveal that researchers are making rapid progress in understanding cellular senescence mechanisms. Several promising research directions are emerging:

Senolytic Drugs

Senolytics are drugs designed to selectively kill senescent cells. Early research shows these compounds can reduce the senescent cell burden and improve age-related diseases in animal models.

Senomorphic Compounds

Senomorphics are drugs that don't kill senescent cells but instead inhibit their harmful SASP secretion, reducing inflammation without eliminating the cells entirely.

Immunotherapy Approaches

Because CD8+ T cell aging impairs immune function, researchers are developing therapies to restore senescent immune cell function, potentially through checkpoint inhibitors or cellular therapies.

Lifestyle and Prevention

Research emphasizes that many senescence-triggering factors like oxidative stress and inflammation are influenced by lifestyle choices including diet, exercise, and stress management.

FAQ: Your Questions About Cellular Senescence Answered

Q: Is cellular senescence the same as aging?

A: No, but they're closely related. Cellular senescence is one of several biological processes that drive aging. Researchers have identified multiple hallmarks of aging, and senescence is one important mechanism among many.

Q: Can we reverse cellular senescence?

A: Potentially, yes. Early research on senolytic and senomorphic drugs shows promise in clearing senescent cells or reducing their harmful effects. However, complete reversal remains an area of active research.

Q: Is cellular senescence always bad?

A: Not entirely. Early in life, cellular senescence serves as a protective mechanism against cancer. The problem arises when senescent cells accumulate over decades, creating chronic inflammation and dysfunction.

Q: How quickly do cells become senescent?

A: This varies. Some cells become senescent after 50-70 divisions (the Hayflick limit). Others become senescent rapidly in response to acute DNA damage or severe oxidative stress. The timeline depends on the cell type and triggering stimulus.

Q: Can I test whether my cells are senescent?

A: Currently, measuring cellular senescence requires specialized laboratory tests that examine tissue samples. Non-invasive biomarkers are an active area of research but aren't yet available for routine clinical use.

Q: What can I do to reduce cellular senescence?

A: Research suggests several approaches: regular exercise, Mediterranean-style diet, stress reduction, adequate sleep, limiting UV exposure, and avoiding smoking. These interventions reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, slowing senescence accumulation.

Q: Are there medications available to treat cellular senescence?

A: While several senolytics and senomorphics are in clinical trials, none are yet FDA-approved for routine clinical use. However, this landscape is rapidly changing, and several promising candidates are advancing through development.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know

Cellular senescence is a key biological process in aging where cells stop dividing but remain metabolically active and potentially harmful

The hallmarks of cellular senescence include permanent cell cycle arrest, altered gene expression, and increased SASP secretion

Senescent cells accumulate with age, contributing to age-related diseases including cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer

CD8+ T cell aging and senescence impair immune function, increasing disease susceptibility in older adults

The relationship between cellular senescence and cancer is complex—senescence prevents early cancer but accumulated senescent cells can promote malignancy

Emerging therapies including senolytics and senomorphics target senescent cells, showing promise in preclinical studies

Lifestyle modifications that reduce oxidative stress and inflammation may slow senescence accumulation

Understanding senescence mechanisms opens therapeutic opportunities for extending healthspan—the years we live in good health

Semantic Keywords for Deeper Understanding

As you explore cellular senescence further, these related terms will deepen your understanding:

Cellular aging and cellular senescence (the process of cells becoming old)

Senescence markers and biomarkers of aging (ways to identify senescent cells)

Telomere shortening and telomere biology (chromosome aging)

Replicative senescence (aging due to division limits)

Stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) (early aging from stress)

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal, a senescence marker)

Inflammaging (chronic inflammation with aging)

Immunosenescence (aging of the immune system)

Senomorphics and senolytics (anti-senescence treatments)

Healthspan (years lived in good health, distinct from lifespan)

Author’s Note

As a clinician, researcher, and educator deeply involved in the fields of metabolism, aging biology, and chronic disease, my goal in writing this article is to bridge the gap between cutting-edge scientific research and practical, evidence-based understanding. Cellular senescence is one of the most transformative areas of aging science, yet it is often misunderstood or oversimplified.

The insights presented here are grounded in peer-reviewed research, including landmark studies published between 2024 and 2026, and reflect the rapidly evolving understanding of how senescent cells contribute to age-related diseases. I intend to provide readers—from students and clinicians to health enthusiasts—with a clear, accurate, and accessible overview of a complex biological process that has profound implications for modern medicine.

While the science of senescence is advancing at remarkable speed, we are still in the early stages of translating these findings into real-world clinical therapies. I encourage readers to approach emerging anti-aging interventions with curiosity but also with caution, prioritizing evidence-based strategies and ongoing scientific developments.

Thank you for taking the time to explore this topic. I hope this article deepens your understanding and inspires further interest in the biology of aging and the pursuit of healthier, longer lives.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Mitochondria, Motor Units, and Muscle Aging: A Complete Guide | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise and Longevity: The Science of Protecting Brain and Heart Health as You Age | DR T S DIDWAL

The Science of Healthy Brain Aging: Microglia, Metabolism & Cognitive Fitness | DR T S DIDWAL

The Aging Muscle Paradox: How Senescent Cells Cause Insulin Resistance and The Strategies to Reverse It | DR T S DIDWAL

VO2 Max & Longevity: The Ultimate Guide to Living Longer | DR T S DIDWAL

Waist-Calf Ratio: The Longevity Metric Most People Aren’t Tracking | DR T S DIDWAL

Blue Zones Secrets: The 4 Pillars of Longevity for a Longer, Healthier Lifepost | DR T S DIDWAL

Anabolic Resistance: Why Muscles Age—and How to Restore Their Growth Response | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Ajoolabady, A., Pratico, D., Bahijri, S., et al. (2025). Hallmarks and mechanisms of cellular senescence in aging and disease. Cell Death Discovery, 11, 364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-025-02655-x

He, Z., Guo, F., Zhao, Q., & Lu, W. (2026). CD8+ T cell aging, senescence, and related disease. Science China Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-025-3101-7

Tenchov, R., Sasso, J. M., Wang, X., & Zhou, Q. A. (2024). Aging hallmarks and progression and age-related diseases: A landscape view of research advancement. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 15(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00531

Yamauchi, S., & Takahashi, A. (2025). Cellular senescence: mechanisms and relevance to cancer and aging. The Journal of Biochemistry, 177(3), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvae079