Waist-Calf Ratio: The Longevity Metric Most People Aren’t Tracking

Want to live longer? Learn how improving your waist–calf ratio helps burn visceral fat, build lower-body muscle, and optimize metabolic health.

AGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/2/202616 min read

For decades, body weight and Body Mass Index (BMI) have dominated conversations around health and disease risk. Yet many patients—and even clinicians—have sensed a disconnect: people with “normal” BMI still develop diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or frailty, while others with higher body weight remain metabolically healthy. Emerging research now confirms what physiology has long suggested—where fat is stored and how much muscle you retain matter more than what the scale says.

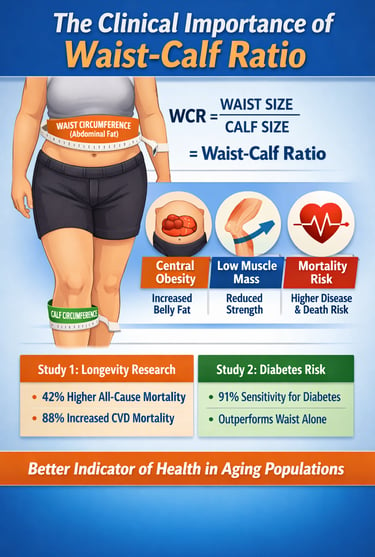

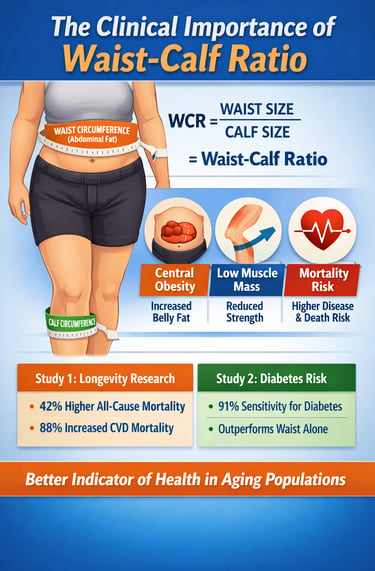

The waist–calf ratio (WCR) is a simple yet powerful anthropometric marker that captures the balance between central obesity and skeletal muscle mass, two critical determinants of healthy ageing, metabolic health, and mortality risk. By combining waist circumference (a surrogate for visceral adiposity) with calf circumference (a validated proxy for lower-body muscle mass), WCR provides a more biologically meaningful assessment of body composition than BMI alone (Dai et al., 2023).

Large population studies show that a higher WCR is strongly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, type 2 diabetes risk, sarcopenia, and frailty, particularly in older adults (Cacciatore et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2025). Importantly, this metric is inexpensive, non-invasive, and easily measured in clinical practice—making it highly relevant for preventive medicine, geriatric care, and metabolic risk screening.

As the science of body composition, muscle preservation, and longevity evolves, the waist–calf ratio may represent a practical shift toward more personalized, physiology-based health assessment—one that moves beyond weight alone and focuses on what truly predicts long-term health.

Clinical Pearls

1. The "Skinny Fat" Detection Tool

BMI often fails older adults because it cannot distinguish between protective muscle and inflammatory fat. You can have a "normal" BMI but a dangerously high WCR. This ratio acts as a high-definition lens, identifying sarcopenic obesity—a condition where hidden muscle loss is masked by stable or increasing abdominal fat.

2. The Calf is a "Metabolic Buffer"

Your calf circumference is more than just a measurement of lower-body size; it is a proxy for your physiological reserve. Larger, stronger calves act as a metabolic sink for glucose and a buffer against systemic inflammation. In adults over 80, a robust calf circumference is one of the strongest independent predictors of longevity.

3. Central Fat is a "Chemical Factory"

The fat measured by your waist circumference (visceral fat) isn't dormant energy storage; it is an active endocrine organ. It pumps out pro-inflammatory cytokines that stiffen arteries and impair insulin signaling. WCR is powerful because it penalizes the "inflammatory factory" (waist) while rewarding the "metabolic engine" (calf).

4. Precision Thresholds for Diabetes

While a general WCR of under 2.9 is a good starting point, the "clinical sweet spot" for preventing Type 2 Diabetes is narrower. Research suggests aiming for a ratio below 2.35 for men and 2.12 for women. Crossing these thresholds provides 91% sensitivity in identifying metabolic risk, often before blood sugar tests show a problem.

5. Strength Training is "Medicine for the Ratio"

You cannot "spot-reduce" fat, but you can "spot-build" muscle. Strength training is the only intervention that simultaneously shrinks the numerator (waist) by boosting resting metabolic rate and expands the denominator (calf) through hypertrophy. This dual-action shift is the most effective way to lower mortality risk.

6. Function Follows Form

A rising WCR is often an early warning sign of frailty and sarcopenia before physical symptoms like falls or weakness occur. By monitoring this ratio monthly, patients and providers can intervene with nutritional (protein) and physical (resistance) therapy while the body still has the "plasticity" to adapt and recover.

Waist-Calf Ratio: An Emerging Anthropometric Marker of Longevity and Mortality Risk

What Is the Waist-Calf Ratio?

The waist-calf ratio is calculated by dividing your waist circumference by your calf circumference. That's it—simple arithmetic with profound health implications. A healthy WCR is generally considered below 2.9, with higher ratios indicating potential health concerns and increased mortality risk.

Here's why this ratio is so revealing: your waist circumference reflects abdominal fat accumulation, particularly visceral fat, which wraps around your organs and triggers inflammation. Meanwhile, your calf circumference serves as a proxy for lower-body muscle mass, a critical indicator of overall strength, metabolic health, and functional capacity. By combining these two measurements, WCR provides insight into the critical balance between harmful fat distribution and protective muscle mass.

The Limitations of BMI in Aging Populations

While BMI revolutionized health assessment decades ago, its shortcomings in older adults are now well-documented. Traditional BMI calculation—weight divided by height squared—fails to account for the fundamental changes that accompany aging. As we grow older, several physiological shifts occur:

Muscle loss: We naturally lose 3-8% of muscle mass per decade after age 30

Fat redistribution: Weight migrates from subcutaneous areas to the abdomen

Bone density reduction: Skeletal weight decreases without corresponding health benefits

Age-related changes: Vascular health, physiological reserve capacity, and stress response all decline

These changes mean that an older adult with a lower BMI may actually be at higher mortality risk due to insufficient muscle mass, while someone with a slightly elevated BMI might be protected by robust musculature. The BMI paradox reveals that in older populations, lower BMI sometimes correlates with increased all-cause mortality, particularly from respiratory disease mortality.

The Research Evidence: What Studies Reveal About WCR and Longevity

Study 1: The Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey and Mortality Risk

Study Details: Dai et al (2023) conducted groundbreaking research involving 4,627 adults aged 65 and older from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. This cohort study examined the relationship between waist-calf ratio, waist circumference, calf circumference, and BMI with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality.

Key Findings:

Individuals in the highest WCR quartile experienced a 42% higher risk of all-cause mortality

The same group showed an 88% increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality—a particularly striking finding

There was a 37% higher risk of mortality from other causes

Low calf circumference was independently associated with increased all-cause mortality risk, higher CVD mortality, and greater death from other causes, especially in adults aged 80 and older

Waist circumference alone showed limited predictive value, primarily correlating with cancer mortality

Key Takeaway: The WCR emerges as a superior predictor of mortality compared to traditional metrics, specifically because it captures both the harmful effects of abdominal obesity and the protective role of lower-body muscle mass. The dramatic 88% increased risk of CVD mortality in the highest WCR quartile underscores the connection between central adiposity, reduced muscle mass, and cardiovascular disease.

Study 2: Diabetes Risk Prediction and WCR

Study Details: Cacciatore et al (2024) investigated whether the waist-to-calf circumference ratio could serve as a practical diabetes risk indicator in 8,900 participants (mean age 57.1 years, 55% women) from the Longevity Check-Up (Lookup) 8+ study.

Key Findings:

The study found a 9.4% prevalence of diabetes in the cohort

WCR showed a significant positive association with diabetes risk (p < 0.001)

Logistic regression confirmed this relationship even after statistical adjustments for confounding variables

Optimal WCR cut-off values were 2.35 for men and 2.12 for women

At these thresholds, WCR demonstrated 91%-92% sensitivity and 74%-75% specificity for identifying individuals at diabetes risk

Importantly, WCR outperformed waist circumference alone, offering superior predictive accuracy

Key Takeaway: WCR proves to be a cost-effective, clinically practical tool for diabetes screening, particularly valuable in resource-limited settings where sophisticated testing may be unavailable. The high sensitivity and specificity suggest that a simple waist and calf measurement could identify most individuals at risk, allowing for early intervention and lifestyle modification.

Study 3: WCR and Severe Sarcopenia in Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain

Study Details: Kim et al (2025) explored the relationship between waist-calf circumference ratio and sarcopenia in 592 older adults (aged ≥65 years) suffering from chronic low back pain. Researchers assessed sarcopenia using the 2019 Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia criteria and compared outcomes across four groups stratified by WCR.

Key Findings:

A significant association existed between higher WCR and severe sarcopenia prevalence

Patients with elevated WCR exhibited more comorbidities and longer pain duration

Low grip strength and poor physical performance were more prevalent in high-WCR individuals

Interestingly, low muscle mass was not consistently associated with high WCR, suggesting that muscle strength and functional capacity matter more than bulk alone

Multivariable analysis confirmed that high WCR independently predicted severe sarcopenia

Key Takeaway: WCR serves as a valuable early-warning indicator for sarcopenia, a condition characterized by age-related muscle loss, reduced strength, and impaired physical performance. This is especially important for vulnerable populations like older adults with chronic pain, where identifying sarcopenia early could guide targeted interventions to maintain independence and quality of life.

Study 4: WCR and Body Composition, Physical Performance, and Muscle Strength in Older Women

Study Details: Arteaga-Pazmiño et al (2025) examined the association between waist-calf circumference ratio, body composition, physical performance, and muscle strength in older women. This research provides sex-specific insights into how WCR correlates with functional health markers in women.

Key Findings:

WCR showed significant correlations with overall body composition metrics

The ratio was associated with physical performance outcomes

Muscle strength measurements varied significantly across WCR categories

The findings support WCR as a comprehensive health indicator for older women

Key Takeaway: Sex-specific analysis reveals that WCR's relationship with health outcomes holds true across genders, though the specific mechanisms and optimal thresholds may differ slightly in women compared to men. This underscores the need for personalized health assessment rather than one-size-fits-all metrics.

Study 5: WCR and Frailty in Older Adults

Study Details: Dai et al (2023) investigated whether waist-calf circumference ratio was associated with frailty in older adults through a prospective cohort study, expanding our understanding of WCR's relationship with age-related conditions.

Key Findings:

WCR demonstrated predictive value for frailty risk in older populations

The metric captured the complex interplay between abdominal fat accumulation and muscle mass loss

Results suggest WCR could serve as a screening tool for frailty, a critical geriatric syndrome

Key Takeaway: Beyond mortality and disease, WCR predicts frailty, a fundamental concern in aging. Early identification of frailty risk allows for proactive interventions targeting physical activity and nutritional support, potentially preserving independence and quality of life.

The Science Behind WCR: Why This Ratio Matters Physiologically

Central Obesity and Its Hidden Dangers

Central obesity—excess fat stored around the abdomen—is far more dangerous than fat distributed elsewhere. Visceral fat, the deep abdominal fat surrounding organs, is metabolically active and pro-inflammatory. It secretes harmful compounds including inflammatory cytokines, adipokines, and oxidative stress markers that damage vascular tissue, impair glucose metabolism, and promote insulin resistance.

High waist circumference indicates elevated central adiposity, which explains the strong correlation with:

Cardiovascular disease and mortality

Type 2 diabetes development

Metabolic syndrome

Chronic inflammation

Atherosclerosis progression

The Protective Power of Muscle Mass

In stark contrast, adequate muscle mass serves as a metabolic and functional powerhouse. Your calf muscles and lower-body musculature provide multiple protective benefits:

Metabolic Protection: Muscle tissue has a high metabolic rate, burning calories at rest and improving insulin sensitivity. This protective effect explains why individuals with robust calf circumference show reduced mortality risk despite potentially higher overall weight.

Inflammatory Defense: Adequate muscle mass acts as a buffer against chronic inflammation by improving glucose clearance, enhancing immune function, and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production. This mechanism partly explains the protective effect against cardiovascular disease mortality.

Functional Capacity: Strong leg muscles maintain balance, gait stability, and the ability to perform daily activities independently. This functional reserve becomes increasingly critical with age, as falls and immobility represent major mortality risk factors.

Stress Resistance: Muscle tissue contributes to overall physiological reserve capacity, the body's ability to adapt to stress, illness, and environmental challenges. This reserve becomes especially important in older age.

Age-Related Changes Amplify WCR's Importance

As we age, several physiological changes make body composition assessment even more critical:

Vascular health decline: Blood vessels become stiffer and less reactive

Stress response impairment: The body's ability to manage physiological stress diminishes

Metabolic shifts: Age-related metabolic changes make weight management more challenging

Inflammation amplification: "Inflammaging" increases baseline inflammatory state

Reserve capacity reduction: The body has less capacity to bounce back from illness or injury

In this context, maintaining muscle mass and controlling abdominal fat becomes not just a cosmetic concern but a genuine longevity strategy.

Practical Applications: How to Measure and Interpret Your WCR

Measuring Your Waist-Calf Ratio: A Step-by-Step Guide

Taking these measurements accurately is straightforward and requires only a flexible measuring tape:

Waist Circumference:

Stand relaxed with your feet hip-width apart

Place the measuring tape around your waist at the narrowest point (typically at the level of your belly button)

The tape should be snug but not tight—you should be able to fit one finger between the tape and your skin

Record the measurement in centimeters or inches

Calf Circumference:

Stand with your feet slightly apart

Place the measuring tape around the widest point of your calf muscle

Keep the tape parallel to the floor

Again, the tape should be snug without compression

Record the measurement in the same units as your waist measurement

Calculate Your WCR: Simply divide your waist circumference by your calf circumference. For example, if your waist is 90 cm and your calf is 35 cm, your WCR would be 2.57.

Interpreting Your Results

A healthy WCR is generally considered below 2.9, though research suggests that optimal values may be lower, particularly for diabetes screening (2.12 for women, 2.35 for men). However, individual context matters:

Your age: Aging naturally affects body composition

Your gender: Women and men may have different optimal thresholds

Your overall health: Chronic conditions and medications influence interpretation

Your fitness level: Exercise history affects muscle mass independent of WCR

Rather than viewing WCR as an absolute judgment, use it as a trend indicator. Regular monitoring helps you track whether your muscle mass is stable, your abdominal fat is decreasing, or your WCR is improving—all positive signs.

Note on Ethnic and Racial Variance

It is critical to recognize that "ideal" thresholds for the waist-calf ratio are not universal. Because populations vary in their genetic predisposition for visceral fat storage and muscle distribution, a one-size-fits-all cutoff can be misleading:

Asian Populations: Generally require lower waist circumference thresholds. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) suggests cutoffs of 90 cm for men and 80 cm for women of South Asian, Chinese, and Japanese descent to account for a higher risk of metabolic disease at lower BMIs.

African-American Populations: Often exhibit higher muscle density and lower visceral fat for the same waist circumference compared to Caucasians, which may slightly elevate the "healthy" WCR threshold without increasing mortality risk.

Clinical Implications: For global accuracy, the WCR should be interpreted using the specific waist circumference guidelines established for the patient's ethnic background to avoid underestimating risk in high-vulnerability groups.

Strength Training: The Dual-Action Strategy for Improving WCR

If you want to improve your waist-calf ratio, strength training is your most powerful tool. Here's why: strength training simultaneously addresses both components of the ratio—reducing the numerator (waist) and increasing the denominator (calf).

Reducing Waist Circumference Through Strength Training

Building Metabolic Muscle: When you engage in resistance training, particularly compound movements, you build lean muscle mass throughout your body. This increased musculature raises your resting metabolic rate, meaning you burn more calories throughout the day without any additional effort. This metabolic boost makes fat loss—especially abdominal fat loss—more achievable.

Core Strengthening: While "spot reduction" isn't possible, targeted core exercises (abdominal crunches, planks, pallof presses, and anti-rotation movements) strengthen your abdominal muscles and improve posture. Combined with overall fat loss from increased calorie burn, this creates visible improvements in waist circumference.

Visceral Fat Reduction: Research consistently shows that aerobic exercise combined with resistance training preferentially reduces visceral fat, the dangerous deep abdominal fat that drives inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk. The metabolic effect of building muscle accelerates this beneficial fat loss.

Increasing Calf Circumference Through Targeted Exercise

Calf-Specific Exercises:

Seated calf raises: Builds the soleus muscle under the gastrocnemius

Standing calf raises: Targets the gastrocnemius, the visible calf muscle

Single-leg calf raises: Increases intensity and addresses muscle imbalances

Donkey calf raises: Provides significant resistance for muscle growth

Compound Lower-Body Exercises:

Squats: Indirectly engage and load the calf muscles

Lunges: Require calf stabilization during movement

Deadlifts: Full-body movement that activates lower-leg musculature

Leg presses: Provide calf engagement with controlled resistance

Progressive Overload: To maximize calf muscle hypertrophy, gradually increase resistance, volume, or intensity over time. Muscles adapt and grow when challenged beyond their current capacity.

A Balanced Training Approach

The most effective approach combines:

Resistance training (3-4 days weekly) for overall muscle building

Aerobic activity (150 minutes weekly moderate intensity) for fat loss

Adequate protein intake (1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram body weight) for muscle repair and growth

Consistent effort over months to see meaningful changes in WCR

Progressive improvement in your WCR reflects meaningful physiological changes: increased muscle strength, improved metabolic health, and reduced mortality risk. This metric transforms from a simple number into evidence of your improving health.

Key Takeaways: What Every Older Adult Should Know

WCR surpasses BMI: The waist-calf ratio provides superior mortality risk prediction compared to traditional BMI by accounting for both central obesity and protective muscle mass.

Muscle mass is life-protective: Low calf circumference independently predicts increased mortality risk, particularly in those 80 and older. Building and maintaining muscle mass is genuinely one of your best longevity strategies.

Where you carry weight matters: Central obesity poses greater health risks than distributed weight gain. Abdominal fat drives inflammation, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease.

WCR predicts multiple health outcomes: Research demonstrates that WCR successfully predicts:

All-cause mortality

Cardiovascular disease mortality

Diabetes risk

Sarcopenia severity

Frailty risk

Individual WCR thresholds matter: While 2.9 is a general benchmark, diabetes screening suggests lower thresholds (2.12-2.35), and individual factors require personalized interpretation.

Simple measurements reveal complex health: Unlike expensive tests requiring laboratory facilities, WCR measurement needs only a tape measure and a few minutes—making it ideal for clinical practice and self-monitoring.

Strength training transforms both metrics: By building calf muscle and reducing abdominal fat simultaneously, resistance exercise directly improves WCR while conferring multiple additional health benefits.

Early assessment enables early intervention: Regular WCR monitoring allows healthcare providers and individuals to identify risk early, enabling lifestyle modifications before disease develops.

Frequently Asked Questions About Waist-Calf Ratio

Q: How does WCR differ from waist-to-hip ratio (WHR)? A: While waist-to-hip ratio has been used to assess central obesity, WCR offers superior value by incorporating muscle mass (calf circumference) alongside central fat measurement. This makes WCR more reflective of overall body composition and functional health.

Q: Can I have a good WCR with high overall weight? A: Absolutely. A person with higher total weight but substantial muscle mass and relatively controlled abdominal fat might have a favorable WCR. This illustrates why WCR is superior to BMI for assessing true health risk.

Q: How often should I measure my WCR? A: Monthly measurements provide adequate frequency for tracking trends without obsessive monitoring. Significant changes in WCR take weeks to months to manifest, so more frequent measurement isn't more informative.

Q: Is my WCR fixed, or can I improve it? A: WCR is absolutely modifiable through lifestyle changes. Consistent strength training, adequate protein intake, aerobic activity, and overall calorie management can meaningfully improve your WCR over 12-24 weeks.

Q: What if I have a high WCR? Should I panic? A: An elevated WCR indicates increased health risk but is not a diagnosis. Think of it as actionable information—a signal that lifestyle modifications targeting muscle gain and fat loss could significantly improve your health trajectory. Many people have improved their WCR substantially through consistent effort.

Q: Does age change how I should interpret WCR? A: Yes. Aging naturally affects body composition, so very high WCR values in younger adults might warrant more concern than the same values in someone 85 years old. Trends are more important than absolute numbers.

Q: Can I measure WCR at home accurately? A: Yes. A flexible measuring tape and careful attention to proper measurement technique allow accurate self-measurement. If possible, have someone help ensure the tape is level and not twisted.

Q: Why is calf circumference specifically important, not just any muscle? A: Calf muscles are accessible to measure, require weight-bearing activity (walking, climbing stairs), and reflect overall lower-body strength and muscle mass. They're excellent proxy indicators for total muscular health, though building muscle anywhere benefits overall physiology.

Q: Should healthcare providers measure WCR for all patients? A: Research increasingly supports incorporating WCR assessment into standard health evaluations, particularly for older adults, those with metabolic concerns, or individuals with chronic diseases. It requires minimal time and cost while providing valuable insight.

A Call to Action: Take Control of Your Health Trajectory

The emerging evidence surrounding the waist-calf ratio carries a powerful message: your health and longevity are not fixed by genetics or age. They're influenced profoundly by factors you can control—specifically, your muscle mass and your fat distribution.

For Healthcare Providers:

Integrate WCR assessment into your standard patient evaluations, particularly for older adults. This simple anthropometric measure costs nothing and takes minutes, yet it provides superior mortality risk prediction compared to BMI. Use WCR results to:

Identify at-risk individuals for targeted intervention

Monitor the effectiveness of lifestyle modification programs

Guide discussions about the importance of strength training

Recognize that higher weight with robust muscle mass may be healthier than lower weight with insufficient musculature

For Older Adults:

Recognize that the scale weight is only one small piece of your health puzzle. Instead:

Prioritize muscle maintenance through regular strength training (2-3 days weekly)

Ensure adequate protein intake (1.2-1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight)

Monitor your body composition through regular WCR measurement

Engage in daily movement—walking, gardening, climbing stairs

Seek professional guidance from fitness professionals experienced with aging populations

Be patient with progress—meaningful muscle gain takes weeks to months, but the health benefits are profound

For Everyone Interested in Healthy Aging:

Your age is not destiny. The physiological changes accompanying aging are real, but they're not inevitable destinies. Every study presented here demonstrates that body composition intervention works. People across age groups can build muscle, reduce harmful fat, and meaningfully improve their WCR. This improvement translates directly into reduced mortality risk, improved physical function, better metabolic health, and enhanced quality of life.

The science is clear: Focus not on the scale weight, but on the mirror, on how your clothes fit, on your strength and endurance, on your waist-calf ratio. These markers reveal your true health status far better than any single number. Commit to the dual strategy of building muscle and reducing abdominal fat. Embrace strength training not as a cosmetic pursuit but as a genuine longevity practice. Monitor your progress with the simple, practical metric of WCR.

Your future health depends less on where you are today and more on the direction you choose to move. Every single strength training session, every walk, every balanced meal with adequate protein is a vote for a longer, healthier, more independent future. Make today the day you commit to improving your body composition and, with it, your longevity and quality of life.

Author’s Note

This article is intended to translate emerging research on the waist–calf ratio into clinically meaningful insight for real-world use. While growing evidence suggests that the waist–calf ratio is a strong predictor of mortality, metabolic risk, frailty, and sarcopenia—often outperforming traditional measures such as BMI—it should not be interpreted as a diagnostic tool in isolation.

Most of the data discussed here are derived from large observational cohort studies. These studies identify important risk patterns but do not establish direct cause-and-effect relationships. Individual factors such as age, ethnicity, baseline fitness, chronic illness, and medication use can meaningfully influence both waist and calf measurements and should always be considered when interpreting results.

In clinical practice, I have found that measures reflecting muscle reserve—particularly lower-body strength—often provide early warning signs of declining metabolic and functional health long before laboratory abnormalities appear. The true value of the waist–calf ratio lies not in the number itself, but in how it redirects attention toward preserving muscle mass, reducing visceral fat, and maintaining physical independence with aging.

Readers should view the waist–calf ratio as a practical screening and monitoring tool that complements, rather than replaces, comprehensive clinical assessment

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

.Related Articles

The Science of Healthy Brain Aging: Microglia, Metabolism & Cognitive Fitness | DR T S DIDWAL

The Aging Muscle Paradox: How Senescent Cells Cause Insulin Resistance and The Strategies to Reverse It | DR T S DIDWAL

VO2 Max & Longevity: The Ultimate Guide to Living Longer | DR T S DIDWAL

Blue Zones Secrets: The 4 Pillars of Longevity for a Longer, Healthier Lifepost | DR T S DIDWAL

Anabolic Resistance: Why Muscles Age—and How to Restore Their Growth Response | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Arteaga-Pazmiño, C., Guzmán-Gurrola, A. L., Fonseca-Pérez, D., Galvez-Celi, J., Aycart, D. F., Álvarez-Córdova, L., & Frias-Toral, E. (2025). Waist-calf circumference ratio is associated with body composition, physical performance, and muscle strength in older women. Geriatrics, 10(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics10040103

Cacciatore, S., Martone, A. M., Ciciarello, F., Galluzzo, V., Gava, G., Massaro, C., Calvani, R., Tosato, M., Marzetti, E., & Landi, F. (2024). Waist-to-calf circumference ratio as a potential indicator of diabetes risk: Results from the longevity check-up (Lookup) 8+. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 28882. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79329-8

Dai, M., Song, Q., Yue, J., Xia, B., Xu, J., Feng, Y., Zheng, M., Zhang, B., Mao, H., & Zhou, B. (2023). Is waist-calf circumference ratio associated with frailty in older adults? Findings from a cohort study. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 492. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04182-9

Dai, M., Xia, B., Xu, J., Feng, Y., Zheng, M., Zhang, B., Mao, H., & Zhou, B. (2023). Association of waist-calf circumference ratio, waist circumference, calf circumference, and body mass index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in older adults: A cohort study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1777. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16711-7

Kim, H. J., Kim, J. Y., & Kim, S. H. (2025). Evaluation of waist-calf circumference ratio to assess sarcopenia in older patients with chronic low back pain: A retrospective observational study. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 20, 299–308. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S503349