Mitochondria, Motor Units, and Muscle Aging: A Complete Guide

Explore the science of muscle aging, mitochondrial dysfunction, and motor unit loss—and how exercise and nutrition can preserve strength at any age.

AGINGSARCOPENIA

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/19/202614 min read

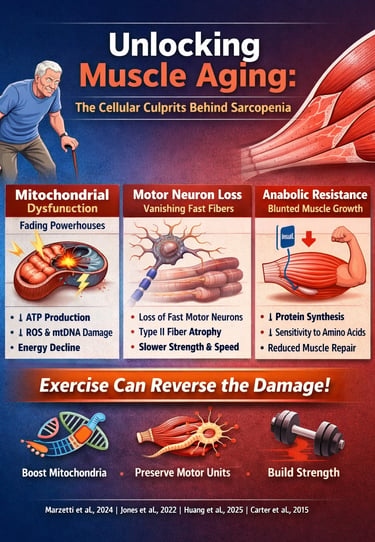

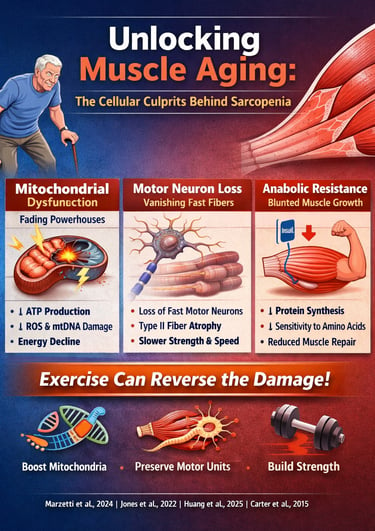

Aging isn’t simply a matter of accumulating birthdays—it is a biological process deeply rooted in cellular decline. One of the most striking and underappreciated examples is muscle aging, the gradual deterioration of strength, power, and mobility that affects millions of older adults worldwide. While most people assume sarcopenia is inevitable, cutting-edge research now reveals the opposite: age-related muscle loss is driven by specific cellular defects that can be slowed, prevented, and even reversed with targeted interventions (Marzetti et al., 2024).

At the center of this decline lies mitochondrial dysfunction, the breakdown of the energy-producing machinery inside muscle fibers. Aging mitochondria produce less ATP, generate more reactive oxygen species, and accumulate mtDNA mutations—creating a metabolic environment that accelerates sarcopenia progression (Huang et al., 2025). These dysfunctional mitochondria disrupt communication between the nucleus and cytosol, impairing protein synthesis and reducing muscle repair capacity.

But mitochondria aren’t the only systems in trouble. Research shows that aging also reshapes the neuromuscular system, leading to the loss of fast motor neurons and selective atrophy of Type II muscle fibers—the ones responsible for explosive strength, balance, and rapid movement (Jones et al., 2022). This explains why older adults lose power far more rapidly than endurance.

Combined with anabolic resistance, where aging muscles become less responsive to dietary protein and insulin, these factors create the perfect storm for muscle decline (Nunes-Pinto et al., 2025). Yet the emerging evidence is clear: exercise—especially progressive resistance training—can restore mitochondrial health, stabilize neuromuscular junctions, and reignite muscle protein synthesis (Carter et al., 2015).

Clinical Pearls

1. Mitochondrial Decay: The "Leaky Battery" Effect

The Science: Sarcopenia is largely driven by mitochondrial dysfunction, where the "power plants" of the cell accumulate DNA damage and leak Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS).

Think of your muscle cells as having thousands of tiny batteries. As we age, these batteries don't just run out of power; they start to "leak" cellular exhaust (oxidative stress) that damages the muscle from the inside out.

The Takeaway: You aren't just losing muscle; your muscle "engines" are becoming less efficient. Exercise acts as a "tune-up" that helps your body recycle these old batteries.

2. Motor Unit Remodeling: The "Wiring" Problem

The Science: Aging causes the selective loss of large alpha-motor neurons, leading to the "orphaning" and subsequent atrophy of Type II (fast-twitch) fibers.

Your muscles move because they are "wired" to your brain. As we age, the wires for our "fast-twitch" fibers (the ones used for power and balance) tend to disconnect first. Your body tries to "re-wire" them to slower nerves, but this makes your movements feel less snappy.

The Takeaway: To keep your balance, you must practice moving with "power"—like standing up quickly from a chair—to keep those fast wires active and connected.

3. Anabolic Resistance: Turning Up the Volume on Protein

The Science: Older muscles exhibit Anabolic Resistance, where the mTOR signaling pathway becomes less sensitive to dietary amino acids (specifically Leucine).

In your 20s, your muscles were "ears open" to the protein you ate. Now, they have become a bit "hard of hearing." A small snack no longer triggers the growth switch. You need a louder signal—a larger, concentrated "dose" of protein—to get the message through.

The Takeaway: Instead of grazing on tiny amounts of protein, aim for one or two "high-volume" protein meals (30–40g) per day to ensure your muscles actually "hear" the signal to rebuild.

4. The SASP "Quiet Fire": Chronic Inflammation

The Science: Sarcopenia is accelerated by inflammaging, where senescent cells release a Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)—a pro-inflammatory cocktail of cytokines like $IL\text{-}6$.

Aging can create a silent, low-grade "fire" in the body called chronic inflammation. This isn't the swelling you feel from a bruise; it’s a constant background chemical noise that tells your body to break down muscle tissue rather than maintain it.

The Takeaway: Anti-inflammatory habits—like eating colorful plants, managing stress, and getting deep sleep—act like a "fire extinguisher" for your muscles, allowing them to stay strong.

5. The Plasticity of Aging: Use It or Lose It

The Science: Despite age-related decline, skeletal muscle maintains a high degree of plasticity, meaning it can still undergo hypertrophy (growth) and mitochondrial biogenesis at any age.

Your muscles are the most adaptable tissue in your body. Even at 80 or 90 years old, your muscle fibers are "listening" for a reason to stay. If you give them a challenge through resistance training, they will respond by repairing the wiring and cleaning up the engines.

The Takeaway: Biological age is negotiable. Your muscles will stay as young as the demands you put on them.

The Age-Old Problem: What Is Sarcopenia?

Sarcopenia—the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function—affects approximately 10% of adults over 60 and up to 50% of those over 80. This isn't just about looking less toned; it's a serious health concern that increases the risk of falls, fractures, disability, and even mortality. But what's really happening inside our muscles?

The story of muscle aging is complex, involving cellular powerhouses called mitochondria, the nervous system connections that control our muscles (motor units), and the delicate balance between building and breaking down muscle proteins. Recent research has revolutionized our understanding of these processes, offering hope for interventions that could help us maintain muscle health throughout our lives.

Mitochondria: The Aging Powerhouses

Understanding Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging Muscles

Think of mitochondria as tiny batteries inside your muscle cells. These organelles generate the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) that fuels every muscle contraction. But here's the problem: these batteries don't age gracefully.

Marzetti et al. (2024) present compelling evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction sits at the heart of sarcopenia development. Their research shows that aging mitochondria experience multiple problems simultaneously—they produce less energy, generate more harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), and struggle to maintain quality control. This creates a vicious cycle where damaged mitochondria accumulate, further compromising muscle function.

Key takeaway from this study: The researchers emphasize that mitochondrial decline isn't just about having fewer mitochondria; it's about having dysfunctional ones that can't effectively communicate with other cellular systems. This mitochondrial-nuclear crosstalk breakdown leads to impaired muscle protein synthesis and accelerated muscle wasting.

The Molecular Mechanisms Behind Mitochondrial Decline

Huang et al. (2025) take us deeper into the molecular machinery, identifying several critical pathways involved in mitochondrial dysfunction during sarcopenia. Their comprehensive review highlights how mitochondrial biogenesis—the process of creating new mitochondria—becomes progressively impaired with age.

The study identifies PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha) as a master regulator of mitochondrial health. This protein acts like a conductor orchestrating multiple processes: mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative phosphorylation, and antioxidant defense. Unfortunately, PGC-1α activity decreases with age, leaving muscles vulnerable to mitochondrial deterioration.

Key takeaway from this study: Huang and colleagues document how mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations accumulate with aging, particularly deletions that affect genes encoding crucial respiratory chain proteins. These genetic errors create a population of damaged mitochondria that produce less ATP while generating more damaging free radicals—a perfect storm for muscle decline.

The researchers also highlight problems with mitophagy, the cellular "recycling program" that removes damaged mitochondria. When mitophagy becomes less efficient, defective mitochondria accumulate, spreading dysfunction throughout the muscle fiber.

Mitochondria and the Bigger Picture of Aging

Nunes-Pinto et al. (2025) place mitochondrial dysfunction within the broader context of biological aging. Their narrative review connects sarcopenia to the nine hallmarks of aging, showing how mitochondrial problems intersect with other age-related changes like genomic instability, telomere attrition, and cellular senescence.

Key takeaway from this study: The authors emphasize that sarcopenia isn't just a muscle problem—it's a systemic aging phenomenon. Mitochondrial dysfunction affects satellite cells (muscle stem cells), reducing their ability to repair and regenerate muscle tissue. This creates a feedback loop where damaged muscles can't effectively recruit the cellular resources needed for recovery.

The study also highlights the role of chronic low-grade inflammation (inflammaging) in accelerating muscle loss. Dysfunctional mitochondria release danger signals that trigger inflammatory responses, which further impair muscle protein synthesis and promote protein degradation.

Exercise as Mitochondrial Medicine

Carter et al. (2015) provide an optimistic perspective by demonstrating that exercise training can partially reverse age-related mitochondrial dysfunction. Their research shows that both endurance exercise and resistance training stimulate mitochondrial adaptations in older adults.

Key takeaway from this study: Regular physical activity increases mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α activation, improves mitochondrial respiratory capacity, and enhances the efficiency of mitophagy. The study reveals that master athletes in their 70s and 80s maintain mitochondrial function comparable to sedentary individuals decades younger—proof that use it or lose it truly applies to cellular health.

The researchers demonstrate that exercise doesn't just increase mitochondrial quantity; it improves quality. Trained older adults show better mitochondrial coupling efficiency, meaning more of the oxygen consumed actually produces usable ATP rather than being lost as heat.

Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Quality Control

Bellanti et al. (2021) focus specifically on how oxidative stress from mitochondrial dysfunction drives sarcopenia progression. Their work explains that aging mitochondria produce excessive ROS, overwhelming the cell's antioxidant defenses.

Key takeaway from this study: The study identifies impaired mitochondrial dynamics—the processes of fusion and fission that maintain mitochondrial health—as a critical factor in sarcopenia. When the balance between fusion (joining mitochondria together) and fission (dividing them) becomes disrupted, mitochondrial networks fragment into dysfunctional pieces that can't efficiently produce energy.

Bellanti and colleagues also document problems with calcium homeostasis in aging muscle mitochondria. Since mitochondria help regulate intracellular calcium levels, their dysfunction affects muscle contraction, protein synthesis, and cellular signaling pathways that control muscle mass.

Motor Units: The Neuromuscular Connection

Understanding Motor Unit Remodeling

While mitochondrial dysfunction happens inside muscle cells, equally important changes occur in how the nervous system controls muscles. Motor units—consisting of a motor neuron and all the muscle fibers it innervates—undergo dramatic remodeling with age.

Jones et al. (2022) provide a comprehensive examination of age-related motor unit remodeling. Their research reveals that we progressively lose motor neurons as we age, particularly the large, fast motor neurons that control type II muscle fibers (the ones responsible for powerful, explosive movements).

Key takeaway from this study: The study documents a remarkable compensatory mechanism: remaining motor neurons sprout new connections to "adopt" orphaned muscle fibers whose original motor neurons have died. This reinnervation process creates larger, less efficient motor units. While this adaptation helps maintain muscle mass temporarily, it comes with functional costs—reduced fine motor control, slower contraction speeds, and increased susceptibility to fatigue.

Jones and colleagues emphasize that exercise training, particularly resistance exercise, can modify motor unit properties even in older adults. High-intensity training helps preserve fast motor units and may stimulate neuromuscular junction stability, the critical connection point between nerve and muscle.

The Neuromuscular Junction in Aging

The neuromuscular junction deserves special attention. This synaptic connection between motor neurons and muscle fibers becomes increasingly fragmented and unstable with age. Marzetti et al. (2024) note that mitochondrial dysfunction at nerve terminals contributes to neuromuscular junction degradation, creating a vicious cycle where metabolic and neurological decline reinforce each other.

Protein Synthesis and Degradation: The Muscle Balance

The Anabolic Resistance Phenomenon

Muscle mass reflects the balance between protein synthesis (building) and protein degradation (breakdown). In healthy young adults, these processes remain balanced, with synthesis increasing after meals and exercise to offset normal breakdown. But aging disrupts this equilibrium.

Nunes-Pinto et al. (2025) describe anabolic resistance—the reduced ability of aging muscles to respond to growth stimuli. Older muscles show blunted responses to amino acids (particularly leucine) and insulin, meaning they build less protein even when provided with adequate nutrients.

Key takeaway: This anabolic resistance partly stems from impaired mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) signaling, a crucial pathway that regulates protein synthesis. Interestingly, while mTOR activation promotes muscle growth, chronic overactivation may contribute to aging through other mechanisms—a paradox researchers are still unraveling.

Protein Degradation Pathways

The flip side of synthesis is breakdown. Several protein degradation systems become overactive with aging, including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Bellanti et al. (2021) explain how mitochondrial dysfunction activates these catabolic pathways through various stress signals.

When mitochondria can't meet energy demands, cells activate AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), which inhibits mTOR and activates autophagy—a protective response that unfortunately contributes to muscle loss when chronically activated.

Diagnostic Advances: Catching Sarcopenia Early

Huang et al. (2025) review emerging diagnostic technologies for detecting sarcopenia and mitochondrial dysfunction before severe muscle loss occurs. Traditional assessments like grip strength, gait speed, and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) provide valuable information, but newer approaches offer cellular-level insights.

Key takeaway: Circulating biomarkers like cell-free mtDNA, inflammatory cytokines, and mitochondrial peptides may soon enable earlier detection of muscle decline. Advanced imaging techniques including magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) can non-invasively assess mitochondrial function in living muscles.

Therapeutic Prospects: Fighting Back Against Muscle Aging

Exercise: The Cornerstone Intervention

Every study examined emphasizes exercise as the most effective intervention for preserving muscle health. Carter et al. (2015) and Jones et al. (2022) both demonstrate that appropriate training protocols can improve mitochondrial function, preserve motor units, and enhance protein synthesis even in advanced age.

Resistance training (lifting weights or using resistance bands) directly stimulates muscle growth and motor unit activation. Endurance exercise (walking, cycling, swimming) improves mitochondrial quality and cardiovascular health. The optimal approach combines both modalities.

Nutritional Strategies

Nunes-Pinto et al. (2025) discuss nutritional interventions targeting anabolic resistance. Higher protein intake (1.2-1.6 g/kg body weight daily) may help overcome blunted protein synthesis in older adults. Leucine supplementation specifically enhances mTOR activation, potentially improving the muscle-building response to meals.

Vitamin D, omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidants show promise in supporting muscle health, though evidence remains mixed regarding optimal doses and combinations.

Pharmacological Approaches

Huang et al. (2025) review emerging pharmacological strategies targeting mitochondrial dysfunction:

NAD+ precursors (nicotinamide riboside, NMN) may enhance mitochondrial function by supporting SIRT1 activity and mitochondrial biogenesis

Urolithin A stimulates mitophagy, helping clear damaged mitochondria

SS-31/Elamipretide directly targets mitochondria to reduce oxidative stress

Myostatin inhibitors block signals that limit muscle growth

While promising, most of these approaches require further research before widespread clinical use.

Addressing Motor Unit Health

Jones et al. (2022) suggest that interventions targeting neuromuscular junction stability might preserve motor unit function. High-velocity resistance training—moving weights quickly—specifically recruits fast motor units, potentially preventing their loss.

The Integrated View: Connecting the Dots

The most important insight from this research collection is that sarcopenia results from interconnected problems across multiple biological systems. Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs energy production, damages cellular components through oxidative stress, and disrupts signaling pathways that regulate protein synthesis. Motor unit loss reduces the nervous system's ability to activate remaining muscle mass. Anabolic resistance prevents muscles from responding normally to nutrition and exercise.

Understanding these connections reveals why multimodal interventions work best. Exercise addresses mitochondrial health, motor unit preservation, and protein metabolism simultaneously. Nutrition supports protein synthesis while potentially reducing oxidative stress. Together, these lifestyle interventions create synergistic benefits that far exceed what any single approach could achieve.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: At what age does sarcopenia typically begin?

A: Muscle mass and strength begin declining around age 30, accelerating after 60. However, the rate varies dramatically based on physical activity, nutrition, and genetics. Inactive individuals may experience significant decline in their 40s, while active adults can maintain excellent muscle function into their 80s.

Q: Can you reverse sarcopenia once it develops?

A: While you can't completely reverse aging, you can significantly improve muscle mass, strength, and function at any age through appropriate resistance training and nutrition. Studies show that even frail 90-year-olds can gain muscle and strength with proper exercise programs.

Q: How much protein do older adults need?

A: Current evidence suggests older adults need 1.2-1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily—higher than the standard recommendation of 0.8 g/kg. Distributing this across meals (20-30g per meal) with emphasis on leucine-rich sources (dairy, meat, eggs) may optimize muscle protein synthesis.

Q: Is walking enough exercise to prevent sarcopenia?

A: While walking provides important cardiovascular benefits, resistance training is essential for maintaining muscle mass and strength. The ideal program combines both: walking or other endurance exercise for mitochondrial health and cardiovascular fitness, plus strength training 2-3 times weekly for muscle maintenance.

Q: Do mitochondrial supplements like CoQ10 or NAD+ boosters really work?

A: Research is promising but preliminary. Some studies show benefits from NAD+ precursors for mitochondrial function, but human trials specifically examining muscle outcomes in aging remain limited. These supplements shouldn't replace exercise and good nutrition, which have proven benefits.

Q: Why do we lose fast-twitch muscle fibers more than slow-twitch?

A: The selective loss of type II (fast-twitch) fibers relates to motor neuron death. Large, fast motor neurons appear more vulnerable to age-related degeneration, possibly due to their higher metabolic demands and longer axons. This explains why power and speed decline more dramatically than endurance with aging.

Take Action: Your Muscle Health Strategy

Understanding the science of muscle aging is empowering—it reveals that decline isn't inevitable. Here's your action plan:

Start strength training today: You don't need a gym membership. Bodyweight exercises, resistance bands, or household objects provide effective resistance. Aim for 2-3 sessions weekly, targeting all major muscle groups.

Move consistently: Incorporate endurance activities you enjoy—walking, swimming, cycling, dancing. Aim for 150 minutes weekly of moderate activity, which supports mitochondrial health and overall vitality.

Optimize your nutrition: Prioritize protein at each meal, emphasizing high-quality sources rich in essential amino acids. Consider working with a registered dietitian specializing in aging for personalized guidance.

Get assessed: If you're over 60 or concerned about muscle loss, ask your healthcare provider about sarcopenia screening. Early detection enables earlier intervention when treatments are most effective.

Stay consistent: The benefits of exercise and nutrition on mitochondrial function and motor unit preservation accumulate over months and years. The best program is one you'll stick with long-term.

Your muscles are remarkably adaptable at any age. The mitochondria that power them, the motor neurons that control them, and the protein machinery that maintains them all respond positively to the right stimuli. By understanding how muscle aging works at the cellular level, you're equipped to make choices that keep you strong, independent, and active throughout your life.

Don't wait for muscle loss to become obvious. Start investing in your muscle health today—your future self will thank you for every rep, every walk, and every protein-rich meal. The science is clear: aging muscles can be remarkably resilient when given what they need to thrive.

Author’s Note

As a clinician and researcher with a deep interest in aging, metabolism, and muscle health, I’ve written this article to bridge the gap between cutting-edge science and practical strategies you can use today. Muscle loss with age—sarcopenia—is not inevitable, and understanding the cellular mechanisms behind it empowers us to take meaningful action.

The science I reference here is drawn from recent, peer-reviewed studies on mitochondrial function, motor unit remodeling, protein synthesis, and the effects of exercise and nutrition. My goal is to provide clear, evidence-based insights while offering actionable guidance for maintaining strength, independence, and quality of life at every stage of adulthood.

This article is intended to educate, inspire, and motivate readers to take charge of their muscle health. While the information provided is grounded in research, it is not a substitute for personalized medical advice. I encourage readers to consult healthcare professionals before starting new exercise or nutrition programs, especially if you have chronic health conditions or concerns about sarcopenia.

Your muscles are resilient. With the right combination of movement, nutrition, and lifestyle choices, you can protect, preserve, and even improve muscle health well into your later years. The science is clear: aging muscles respond, adapt, and thrive when given the proper stimulus.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

How to Prevent and Reverse Muscle Wasting in Chronic Disease (2025 Guide) | DR T S DIDWAL

Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia: The Critical Connection | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Prevent Sarcopenia: Fight Age-Related Muscle Loss and Stay Strong | DR T S DIDWAL

Who Gets Sarcopenia? Key Risk Factors & High-Risk Groups Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Exercises for Sarcopenia: Strength Training Guide for Older Adults | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Bellanti, F., Lo Buglio, A., & Vendemiale, G. (2021). Mitochondrial impairment in sarcopenia. Biology, 10(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10010031

Carter, H. N., Chen, C. C. W., & Hood, D. A. (2015). Mitochondria, muscle health, and exercise with advancing age. Physiology, 30(3), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00039.2014

Huang, Y., Wang, C., Cui, H., Sun, G., Qi, X., & Yao, X. (2025). Mitochondrial dysfunction in age-related sarcopenia: mechanistic insights, diagnostic advances, and therapeutic prospects. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 13, 1590524. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2025.1590524

Jones, E. J., Chiou, S. Y., Atherton, P. J., Phillips, B. E., & Piasecki, M. (2022). Ageing and exercise-induced motor unit remodelling. The Journal of Physiology, 600(8), 1839–1849. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP281726

Marzetti, E., Calvani, R., Coelho-Junior, H. J., & Picca, A. (2024). Mitochondrial pathways and sarcopenia in the geroscience era. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 28(12), 100397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100397

Nunes-Pinto, M., Bandeira de Mello, R. G., Pinto, M. N., Moro, C., Vellas, B., Martinez, L. O., Rolland, Y., & de Souto Barreto, P. (2025). Sarcopenia and the biological determinants of aging: A narrative review from a geroscience perspective. Ageing Research Reviews, 103, 102587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2024.102587