Which Fats Are Best for Heart Health? What Modern Cardiometabolic Science Reveals

Discover which fats are best for heart health. Explore the latest science on saturated, unsaturated, and personalized fat recommendations.

NUTRITIONHEART

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/14/202614 min read

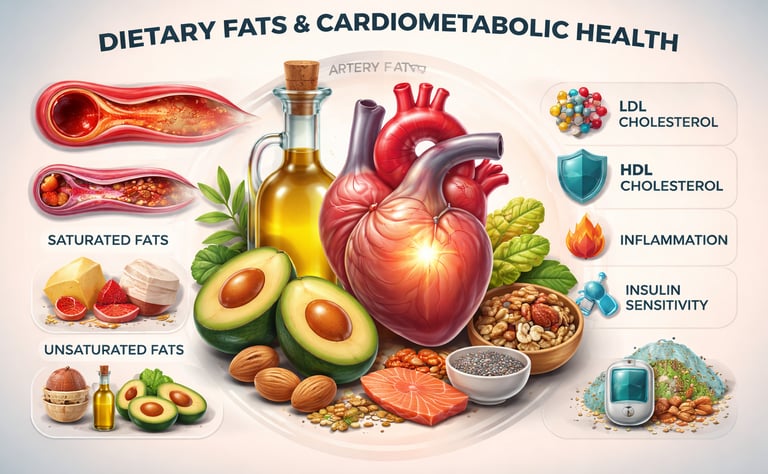

For decades, dietary fat has occupied a paradoxical position in medicine—first demonized as the primary driver of heart disease, then partially rehabilitated, and now reconsidered through the lens of metabolic individuality. The once-simple public health directive to “eat less fat” has given way to a far more sophisticated question: which fats, in which contexts, and for whom? Emerging evidence suggests that the cardiometabolic effects of dietary fat depend less on total quantity and far more on molecular structure, food source, metabolic phenotype, and replacement nutrient (Forouhi et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019).

Large prospective cohort analyses and mechanistic studies now demonstrate that replacing saturated fatty acids (SFA) with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) lowers LDL cholesterol and reduces cardiovascular risk, whereas replacing SFA with refined carbohydrates confers no such benefit (Forouhi et al., 2018). Meanwhile, long-running population studies such as the Framingham Offspring cohort continue to reveal meaningful heterogeneity in individual lipid and metabolic responses to common fats and oils (Zhou et al., 2025). This variability has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward precision nutrition—an approach that integrates lipid profiling, insulin sensitivity, inflammatory markers, and genetic predisposition into dietary guidance (Lovegrove, 2025).

Adding further complexity, contemporary clinical guidance emphasizes that food processing, oxidative stability, and overall dietary pattern may influence cardiometabolic outcomes independently of fat class alone (Miller et al., 2026). In other words, the modern science of dietary fats no longer asks whether fat is “good” or “bad.” Instead, it asks a more biologically meaningful question: how do different fats interact with individual physiology to shape long-term cardiovascular and metabolic health?

Clinical Pearls

1. The "Matrix" Over the Macronutrient

Scientific Perspective: Cardiometabolic risk is dictated more by the food matrix—the complex physical and chemical structure of a food—than by its total saturated fatty acid (SFA) content. Fermented dairy (e.g., cheese and yogurt) shows a neutral or even protective effect on LDL-C and CVD risk despite high SFA levels, likely due to the presence of calcium, phosphorus, and bioactive peptides.

Don't just count fat grams; look at the whole food. For example, the fat in a piece of natural cheese doesn't affect your heart the same way the fat in a processed sausage does. Some "fatty" foods like yogurt can actually be part of a heart-healthy plan because of how the nutrients work together.

2. Isocaloric Substitution and "Replacement Value"

Scientific Perspective: The clinical benefit of reducing SFA is entirely dependent on the replacement macronutrient. Substituting SFA with refined carbohydrates (high glycemic index) yields no reduction in CVD risk; however, replacing SFA with polyunsaturated fats (PUFA) or monounsaturated fats (MUFA) from plant sources significantly improves lipid profiles and endothelial function.

If you take the butter out of your diet but replace it with white bread or sugary snacks, your heart health won't improve. To see a real difference, replace those solid fats with "liquid golds" like olive oil or fats from walnuts and fatty fish.

3. Precision Nutrition: The "APOE" and Metabolic Phenotype

Scientific Perspective: Inter-individual variability in lipid response is significant. Genetic polymorphisms, such as the APOE4 allele, can make certain patients "hyper-responders" to dietary cholesterol and saturated fat. Personalized nutrition should move toward assessing a patient’s unique metabolic phenotype rather than applying a universal 10% SFA ceiling to all populations.

Everyone’s body processes fat differently—it's in your DNA. While your neighbor might thrive on a higher-fat diet, your specific genetics might mean your cholesterol spikes easily. Your diet should be "tailor-made" for your bloodwork and history, not a one-size-fits-all rule.

4. Oxidative Stress and Processing Quality

Scientific Perspective: Beyond the fatty acid profile, the degree of processing and thermal stability are critical. Refined seed oils subjected to high-heat industrial processing may contain oxidation products that promote systemic inflammation. Clinicians should prioritize cold-pressed, minimally refined oils (e.g., EVOO) to support better inflammatory markers.

Not all vegetable oils are the same. Highly processed oils used in deep frying can cause "stress" (inflammation) in your body. Stick to oils that are "cold-pressed" or "extra-virgin," as these keep the natural antioxidants that protect your arteries.

5. Essentiality of Omega-3 Bioavailability

Scientific Perspective: While ALA (alpha-linolenic acid) from plant sources is essential, its conversion rate to EPA and DHA is inefficient in humans (<5-10%). For secondary prevention of CVD and triglyceride management, clinicians should prioritize marine-sourced omega-3s or high-quality algae supplements to ensure adequate serum levels of long-chain fatty acids.

Plant fats like flaxseeds are great, but your heart specifically craves the types of Omega-3s found in fish like salmon or sardines. If you don't eat fish, a high-quality supplement is often better than relying on seeds alone to get the "heart-shielding" fats you need.

The Evolution of Dietary Fat Science: From One-Size-Fits-All to Personalization

Understanding cardiometabolic health—the intersection of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes—requires moving beyond simplistic messages. Modern nutritional research has revealed that individual differences in genetics, lifestyle, and metabolic profiles mean that one person's optimal diet may differ significantly from another's.

Key insight: The relationship between dietary fat intake and cardiovascular outcomes isn't universal; it depends on the type of fat, the individual consuming it, and the overall dietary context.

Recent groundbreaking research from 2025-2026 provides clarity on these pressing questions. This comprehensive guide explores the latest evidence on dietary fats, cardiometabolic outcomes, and personalized nutrition approaches that can help you make informed decisions about your diet and long-term health.

Study 1: Zhou et al. (2025) - Framingham Offspring Cohort Analysis

Zhou, X., Yiannakou, I., Yuan, M., Singer, M. R., & Moore, L. L. (2025) conducted a landmark analysis examining associations of common fats and oils with cardiometabolic health outcomes in the Framingham Offspring cohort. This long-running prospective study, which has tracked thousands of participants for decades, provided researchers with unprecedented access to real-world dietary patterns and health outcomes.

The research focused on identifying which specific types of dietary fats—not just general categories—were most strongly associated with favorable versus unfavorable cardiometabolic markers.

The Framingham analysis revealed several critical insights:

Monounsaturated fats (found predominantly in olive oil, avocados, and nuts) demonstrated the strongest associations with improved cardiovascular outcomes and better metabolic health markers

Polyunsaturated fats showed protective effects, particularly when derived from plant sources rather than processed foods

Common fats and oils consumed in typical diets showed highly variable effects depending on their source and processing methods

Individual variation in response to different fat types was substantial, suggesting that personalized fat recommendations may be more effective than universal guidelines

Practical implication: The type of fat matters significantly. A tablespoon of extra-virgin olive oil is not metabolically equivalent to a tablespoon of refined vegetable oil, despite both being lipids.

This research validates the Mediterranean dietary pattern's emphasis on healthy fats from whole sources and challenges the notion that all dietary fat categories deserve equal dietary restriction. For clinicians and patients alike, the message is clear: fat quality trumps fat quantity in determining cardiometabolic health outcomes.

Study 2: Lovegrove (2025) - Bridging Public Health and Personalized Nutrition

Lovegrove J. A. (2025) addresses a critical gap in contemporary nutrition education: the transition from population-level public health recommendations to individualized dietary interventions. The study's framework—"One for all" and "all for one"—elegantly captures the dual nature of modern nutritional science.

The research emphasizes that while population health guidelines remain essential for broad public benefit, personalized nutrition approaches can provide superior outcomes for individuals with specific metabolic phenotypes, genetic predispositions, or existing cardiometabolic diseases.

Key Takeaways

Public health guidance on dietary fats must remain accessible and practical for the general population, yet should acknowledge individual variation

Personalized nutrition approaches can significantly improve outcomes for people with metabolic dysfunction, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease

Precision nutrition technologies and biomarker assessment enable more tailored recommendations than ever before

The shift toward personalized dietary fats recommendations requires better genetic testing, lipid profiling, and lifestyle assessment

Lovegrove's work highlights an essential reality: your friend's optimal diet may be genuinely different from yours, even if you're both trying to prevent heart disease. Genetic factors like the APOE4 allele, triglyceride metabolism patterns, and insulin sensitivity all influence how your body processes different dietary fat sources.

Clinical application: A comprehensive cardiometabolic health assessment should now include consideration of individual fat responsiveness rather than applying one-size-fits-all recommendations.

Study 3: Forouhi et al. (2018) - Evidence, Controversies, and Consensus

While slightly older than the other studies cited, Forouhi, N. G., Krauss, R. M., Taubes, G., & Willett, W. (2018) remains essential reading for understanding how dietary fat science evolved and where genuine controversies persist. This BMJ review synthesized evidence from thousands of studies to identify where consensus exists and where legitimate scientific debate remains.

The research identified several areas where scientific consensus has solidified:

Trans fats (artificial partially hydrogenated oils) are unequivocally harmful and should be minimized or eliminated

Saturated fat remains controversial; some individuals show metabolic vulnerability, while others appear less sensitive

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fats (from fish and plant sources) provide clear cardiovascular benefits

Replacement foods matter: substituting saturated fat with refined carbohydrates provides no benefit compared to replacing it with unsaturated fats

The authors candidly acknowledged several unresolved debates:

The optimal saturated fat intake for individuals with genetic predispositions to high cholesterol

Whether dietary cholesterol from food sources significantly impacts blood cholesterol levels in most people

The long-term metabolic effects of very low-fat versus moderate-fat, higher-quality-fat diets

Important distinction: The absence of complete scientific consensus doesn't indicate that evidence is lacking—rather, it reflects genuine biological complexity and individual variation in response to dietary interventions.

Study 4: Miller et al. (2026) - A Clinician's Guide for Cardiovascular Nutritional Controversies

Miller, M., Aggarwal, M., Allen, K., Bhattacharya, R., Dastmalchi, L. N., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Klodas, E., Mozaffarian, D., Ostfeld, R. J., Petersen, K. S., Reddy, K. R., & Freeman, A. M. (2026) provides essential practical guidance for clinicians navigating trending cardiovascular nutritional controversies in 2026. As cardiometabolic science evolves rapidly, healthcare providers need updated frameworks to counsel patients effectively.

The 2026 clinician's guide addresses several hot topics:

Fructose and metabolic health: High fructose intake from added sugars, not from whole fruits, correlates with metabolic dysfunction

Ultra-processed foods: Independent of fat content, the ultra-processed nature of foods significantly impacts cardiometabolic outcomes

Seed oils and oxidative stress: Emerging concerns about oxidative stress from high-heat processing of seed oils warrant consideration

Individual responsiveness: Why some individuals thrive on higher fat diets while others don't

Key Takeaways for Patients and Providers

A comprehensive dietary assessment should evaluate not just fat intake but also food quality, processing level, and whole food consumption

Metabolic testing (including lipid panels, glucose tolerance, and inflammatory markers) should guide personalized recommendations

Patient-centered counseling, acknowledging individual variability yields better adherence and outcomes

Study 5: Wu, Micha, & Mozaffarian (2019) - Mechanisms and Effects on Risk Factors

Wu, J.H., Micha, R. & Mozaffarian, D. (2019) provide the mechanistic foundation for understanding how dietary fats influence cardiometabolic disease at the molecular and physiological level. This Nature Reviews Cardiology article explains not just that certain fats matter, but why they matter.

The research describes several key biological pathways:

Lipid Profile Effects:

Different fat types have vastly different effects on LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides

Saturated fats increase LDL more than other dietary fats, though this effect varies individually

Unsaturated fats promote favorable shifts in lipoprotein particles and lipid ratios

Inflammatory and Endothelial Effects:

Dietary fats directly modulate systemic inflammation, endothelial function, and vascular reactivity

Oxidized fats and trans fats promote inflammatory pathways

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fats activate anti-inflammatory mechanisms

Metabolic and Insulin Sensitivity Effects:

Fat quality influences insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism

Processed oils and trans fats worsen insulin resistance

Whole-source unsaturated fats improve metabolic health markers

Understanding these mechanisms empowers informed decision-making. When you choose extra-virgin olive oil over refined vegetable oil, you're not just making a philosophical choice—you're influencing your endothelial function, inflammatory cytokine production, and LDL particle composition in measurably different ways.

The Bottom Line: What All This Research Means for Your Diet

Principles of Evidence-Based Fat Consumption

1. Source Matters More Than Category Not all saturated fats are identical. Saturated fats from coconut oil behave differently than those from grass-fed butter, which differ from those in processed meats. Similarly, polyunsaturated fats from wild salmon are not equivalent to those in seed oils heated to high temperatures.

2. Quality Trumps Quantity While total fat intake remains important for energy balance, the distinction between 25% and 35% of calories from fat is less critical than ensuring those calories come from high-quality fat sources. A diet with 35% calories from high-quality monounsaturated fats may be superior to a diet with 25% from refined polyunsaturated oils.

3. Individual Variability Is Real Your genetics, metabolic profile, and existing health status influence how your body responds to different fat types. The most effective dietary fat approach is personalized based on your unique characteristics, not simply copied from popular diet trends.

4. Processing Matters Substantially Heat-processed vegetable oils, partially hydrogenated oils, and highly refined fats behave very differently from minimally processed alternatives. Cold-pressed oils, whole-food fat sources, and naturally-occurring fats align better with cardiovascular health.

5. Overall Diet Context Is Critical The cardiometabolic health impact of dietary fats depends heavily on what they're replacing and what accompanies them. Monounsaturated fats in a Mediterranean diet rich in vegetables and whole grains provide greater benefit than monounsaturated fats in a diet high in refined carbohydrates.

Clarification on Seed Oils and Evidence Strength

It is important to distinguish between mechanistic concerns and clinical outcome data when discussing refined seed oils. While high-heat processing and oxidation of certain polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-rich oils may raise theoretical concerns regarding oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, large randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses consistently demonstrate that replacing saturated fatty acids (SFA) with polyunsaturated fats lowers LDL cholesterol and reduces cardiovascular events.

Landmark analyses published in journals such as BMJ and Nature Reviews Cardiology support the position that PUFA substitution for SFA improves cardiometabolic outcomes at the population level. Thus, current evidence does not justify blanket avoidance of seed oils, particularly when they replace saturated fats in minimally processed dietary patterns.

The more evidence-based concern lies not in PUFA itself, but in the broader dietary context—especially ultra-processed foods, repeated high-temperature oil reuse, and overall dietary quality.

Practical Recommendations Based on Current Evidence

Fats to Emphasize

Olive oil (especially extra-virgin)

Avocados and avocado oil

Nuts and seeds (in whole form)

Fatty fish (salmon, sardines, mackerel) are rich in omega-3 fatty acids

Grass-fed butter and ghee in moderation

Coconut oil in moderation (despite being saturated, it has unique metabolic effects)

Fats to Limit

Refined seed oils (soybean oil, corn oil, canola oil when highly refined)

Trans fats (partially hydrogenated oils, often in processed foods)

Fats from ultra-processed meats and processed foods

High-heat-cooked oils that have undergone oxidation

Fats to Approach with Individual Consideration

Coconut oil: Beneficial for some individuals, potentially problematic for others with specific lipid profiles

Saturated fat from whole sources: More nuanced than previous guidance suggested

Seed oils in whole seeds: Superior to refined versions

Frequently Asked Questions About Dietary Fats and Cardiometabolic Health

Q1: Are All Saturated Fats Bad for Heart Health?

A: No. Contemporary research shows that the impact of saturated fat on cardiovascular risk varies significantly based on (1) the specific saturated fat source, (2) the individual's genetic profile, and (3) what dietary components the saturated fat is replacing. Saturated fat from whole-food sources like butter from grass-fed cows or coconut affects your metabolism differently than saturated fat from processed meats or refined cakes. The Forouhi et al. (2018) and Wu et al. (2019) research makes clear that individual responsiveness to saturated fat varies based on genes like APOE status.

Q2: Should I Worry About Cholesterol in Foods I Eat?

A: Dietary cholesterol has far less impact on blood cholesterol levels than previously believed. The Forouhi et al. (2018) study highlights this as a lingering controversy in nutrition science, but evidence suggests that for most people, cholesterol from food accounts for only 10-15% of blood cholesterol levels. Your body produces most of your cholesterol endogenously. However, if you have familial hypercholesterolemia or specific genetic factors, dietary cholesterol may matter more—highlighting the need for personalized approaches emphasized by Lovegrove (2025).

Q3: Are Seed Oils Bad?

A: This is complicated. Whole seeds (flax, chia, pumpkin, sunflower) are nutritious. Seed oils in their minimal form—cold-pressed versions—contain beneficial compounds. However, the refined seed oils used in most processed foods have been stripped of nutrients, oxidized through processing, and overheated in manufacturing. The Miller et al. (2026) guide addresses "trending controversies" about seed oils, noting that oxidative stress from high-heat processing warrants consideration. The answer: whole seeds, yes; refined seed oils, limit.

Q4: Is the Mediterranean Diet Really the Gold Standard?

A: The Mediterranean dietary pattern—emphasizing olive oil, fish, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains—has accumulated the most robust evidence for cardiometabolic benefits. All five studies reviewed here align with Mediterranean diet principles. However, Lovegrove (2025) emphasizes that even the Mediterranean diet can be personalized. Someone with specific genetic variants or metabolic phenotypes might benefit from modifications to the traditional Mediterranean pattern.

Q5: Should I Be Concerned About High Fat Diets?

A: "High fat" is meaningless without context. A diet with 40% of calories from high-quality monounsaturated fats (like Mediterranean or ketogenic patterns using whole foods) is fundamentally different from a diet with 40% from processed seed oils and trans fats. The source, type, and context matter far more than the percentage. Wu et al. (2019) and the Framingham analysis (Zhou et al., 2025) show that fat quality, not quantity, drives cardiometabolic outcomes.

Q6: What If I Have High Cholesterol or Triglycerides?

A: This scenario benefits from the personalized approach emphasized across all studies. Miller et al. (2026) highlights metabolic testing as essential for determining your specific phenotype. Some individuals with high cholesterol respond well to increasing unsaturated fats while others benefit more from reducing overall fat intake. Some with high triglycerides respond dramatically to reducing refined carbohydrates and added sugars (often replacing them with healthy fats). Your clinician should assess your specific lipid pattern rather than applying generic recommendations.

Q7: What About Omega-3 Supplements vs. Food Sources?

A: Food sources of omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish like salmon, sardines; plant sources like flaxseeds, walnuts) come packaged with complementary nutrients and compounds. While omega-3 supplements show benefits in research, whole fish sources demonstrate superior cardiometabolic outcomes in observational research like the Framingham study. Prioritize whole fish 2-3 times weekly; consider supplements if that's not feasible.

Key Takeaways: Your Action Plan

What the latest 2025-2026 research clearly shows:

✓ Fat quality matters more than quantity for cardiometabolic health

✓ Personalized nutrition approaches outperform one-size-fits-all recommendations

✓ Processed and refined fats should be minimized; whole-food fat sources prioritized

✓ Mediterranean and similar patterns emphasizing monounsaturated fats, omega-3s, and whole foods show the strongest evidence

✓ Individual variation in fat responsiveness is real and should guide your choices

✓ Ultra-processed foods—regardless of fat type—damage cardiometabolic health

✓ Assessment of your specific lipid profile, metabolic status, and genetic factors enables truly personalized recommendations

Author’s Note

As a physician trained in internal medicine, I have witnessed firsthand how public understanding of dietary fat has oscillated between extremes—first vilified, then celebrated, and often oversimplified in both directions. The science, however, has always been more nuanced than the headlines.

This article was written to clarify—not sensationalize—the evolving evidence surrounding dietary fats and cardiometabolic health. It synthesizes findings from large cohort studies, randomized controlled trials, and mechanistic research to provide a balanced, clinically grounded perspective. Where consensus exists—such as the harms of trans fats or the benefits of replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats—it is clearly acknowledged. Where uncertainty remains—such as individual variability in lipid responses or emerging questions about processing and oxidation—it is presented with appropriate scientific caution.

Nutrition science is complex because human metabolism is complex. Genetics, insulin sensitivity, lipid particle dynamics, inflammatory pathways, and lifestyle factors all shape how an individual responds to dietary fat. For this reason, modern cardiometabolic care must move beyond rigid dogma toward evidence-based personalization.

My goal is not to promote a specific dietary ideology, but to encourage informed decision-making rooted in physiology, clinical evidence, and long-term sustainability. I hope this article empowers readers—clinicians and patients alike—to approach dietary fat not with fear or trend-driven enthusiasm, but with scientific literacy and metabolic awareness.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Can Plant-Based Polyphenols Lower Biological Age? | DR T S DIDWAL

Time-Restricted Eating: Metabolic Advantage or Just Fewer Calories? | DR T S DIDWAL

Can You Revitalize Your Immune System? 7 Science-Backed Longevity Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise and Longevity: The Science of Protecting Brain and Heart Health as You Age | DR T S DIDWAL

Light and Longevity: Can Sunlight Slow Cellular Aging? | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Forouhi, N. G., Krauss, R. M., Taubes, G., & Willett, W. (2018). Dietary fat and cardiometabolic health: Evidence, controversies, and consensus for guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 361, k2139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2139

Lovegrove, J. A. (2025). Dietary fats and cardiometabolic health—From public health to personalised nutrition: 'One for all' and 'all for one'. Nutrition Bulletin, 50(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12722

Miller, M., Aggarwal, M., Allen, K., Bhattacharya, R., Dastmalchi, L. N., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Klodas, E., Mozaffarian, D., Ostfeld, R. J., Petersen, K. S., Reddy, K. R., & Freeman, A. M. (2026). A clinician's guide for trending cardiovascular nutritional controversies in 2026. JACC: Advances, 5(3), 102591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacadv.2026.102591

Wu, J. H., Micha, R., & Mozaffarian, D. (2019). Dietary fats and cardiometabolic disease: Mechanisms and effects on risk factors and outcomes. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 16, 581–601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-019-0206-13

Zhou, X., Yiannakou, I., Yuan, M., Singer, M. R., & Moore, L. L. (2025). Associations of common fats and oils with cardiometabolic health outcomes in the Framingham Offspring cohort. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 79(9), 904–911. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-025-01601-5