The Neuroscience of Obesity: How Excess Adiposity Causes Vascular Dementia and Brain Atrophy

Beyond correlation: 2025-2026 Mendelian randomization studies confirm high BMI as a causal risk factor for dementia. A comprehensive clinical look at neuroinflammation and metabolic brain health

OBESITY

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/4/202613 min read

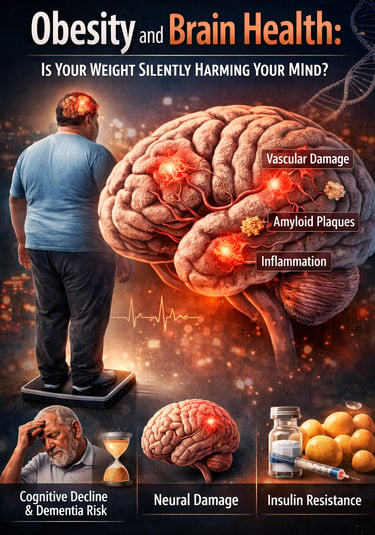

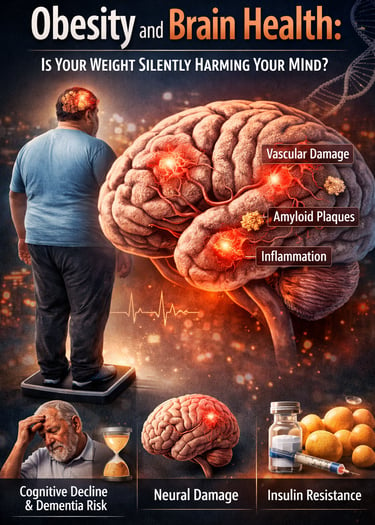

What if the number on your weighing scale today could predict the clarity of your thoughts decades from now? For years, obesity has been framed as a risk factor for diabetes, heart disease, and shortened lifespan. But a growing body of research now reveals a far more unsettling consequence: excess body fat may be silently reshaping your brain long before the first memory lapse appears.

Large-scale neuroimaging and genetic studies published between 2024 and 2026 demonstrate that obesity is not merely associated with cognitive decline—it actively contributes to structural brain changes, impaired neural connectivity, and increased dementia risk (Chwa et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025). Even more striking, these changes occur in cognitively normal adults, meaning individuals may feel mentally sharp while underlying neural damage quietly accumulates.

For decades, scientists debated whether obesity simply “traveled alongside” dementia risk or directly caused it. That debate is now effectively settled. Using Mendelian randomization—a powerful genetic method that mimics randomized trials—researchers have shown that higher body mass index causally increases the risk of vascular-related dementia, independent of lifestyle or socioeconomic confounders (Nordestgaard et al., 2026). In parallel, longitudinal cohort studies reveal that metabolically “healthy” obesity still disrupts brain structure and mood regulation, challenging the notion that excess adiposity is benign if laboratory values appear normal (Wang et al., 2026).

The implications are profound. Obesity-driven vascular dysfunction, chronic neuroinflammation, and insulin resistance converge to compromise cerebral blood flow and neuronal integrity, linking cardiometabolic health directly to cognitive aging (Visseren et al., 2024). In this emerging paradigm, weight management is no longer just about longevity—it is about protecting the very organ that defines identity, memory, and independence.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Midlife Mirror" Effect

Your brain health at 70 is often a reflection of your metabolic health at 45. Research shows that obesity in midlife is a much stronger predictor of future dementia than obesity in later life. This means that managing weight in your 40s and 50s isn't just about heart health; it’s a "deposit" into a cognitive savings account that you will draw from decades later.

2. The Silent Infrastructure Damage

Brain changes due to excess body fat often begin "silently"—meaning they are detectable on advanced imaging long before you notice memory lapses. High body fat can degrade neural connectivity, which acts as the wiring between different brain regions. Think of it as your internal communication network: weight management helps keep the "highways" of your brain clear and fast before the "traffic jams" of cognitive decline begin.

3. The "Healthy Obesity" Myth

The concept of "metabolically healthy obesity"—where someone has a high BMI but normal blood sugar and cholesterol—is increasingly being challenged. New evidence suggests that adiposity (excess fat tissue) itself can be "lipotoxic." This means fat cells can release inflammatory signals that cross the blood-brain barrier and irritate brain tissue, regardless of what your cholesterol numbers say.

4. Vascular Health is Brain Health

The brain is one of the most bloodthirsty organs in the body, requiring a constant, high-pressure supply of oxygen. Obesity often leads to stiffening of the small blood vessels (microvascular disease). When these vessels lose their flexibility, the brain receives less "fuel." Protecting your vascular system through weight control is, quite literally, the best way to keep your brain "hydrated" with the nutrients it needs to function.

5. Dose-Dependent Resilience

Cognitive protection is "dose-dependent," meaning the longer you maintain a healthy weight, the more physical grey matter (the actual processing power of the brain) you tend to preserve. However, the reverse is also true: even modest, sustainable weight loss can begin to "cool" systemic inflammation within weeks, providing an immediate benefit to your brain’s environment. It is rarely too late to start, but sooner is always scientifically superior.

Obesity and Brain Health: What Recent Research Reveals About Your Weight and Cognitive Future

The connection between weight management and cognitive function has emerged as one of the most important health discoveries of the past few years. Multiple large-scale studies provide compelling evidence that maintaining a healthy weight isn't merely about appearance or preventing heart disease. It's fundamentally about preserving the very organ that makes you you—your brain.

This comprehensive guide explores five landmark studies that shed light on the relationship between obesity and dementia risk, metabolic health and brain function, and what you can do about it.

The Big Picture: Understanding the Global Burden

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Systemic Health

Before we dive into brain health specifically, it's essential to understand the broader health landscape. Visseren and colleagues (2024) published a comprehensive analysis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, examining the global burden this condition places on public health systems worldwide.

Key Takeaway: This research establishes that cardiovascular health and metabolic dysfunction are foundational issues affecting millions globally. The significance here is critical: cardiovascular disease shares many risk factors with cognitive decline, particularly obesity and metabolic syndrome. Understanding this connection helps explain why maintaining heart health through weight management directly supports brain health.

Why This Matters for Your Brain: The blood vessels that feed your heart also feed your brain. When obesity damages cardiovascular health, it simultaneously compromises the blood supply to your brain, increasing dementia risk.

The Direct Connection: Obesity, Metabolic Health, and Brain Function

Wang and colleagues (2026) conducted a groundbreaking prospective cohort study examining how obesity and metabolic health directly influence brain health. This study is particularly important because it followed individuals over time, allowing researchers to observe real-world changes.

The research revealed that obesity—even when metabolic markers appear relatively stable—significantly increases the risk of cognitive decline and mood-related disorders. The study's innovative approach separated individuals into categories based on both their weight and their metabolic health status, revealing a nuanced picture.

Individuals with high body mass index (BMI) showed measurable changes in brain structure and function, contributing to increased rates of depression and cognitive difficulties. Importantly, the study found that metabolic dysfunction amplified these risks considerably.

Key Takeaway: You can't simply ignore obesity because your other health numbers look good. Adiposity—the actual accumulation of body fat—directly damages brain tissue, independent of other metabolic factors. This finding challenges the common assumption that "metabolically healthy obesity" is truly healthy.

Practical Implication: This suggests that weight reduction benefits your brain even before improvements in cholesterol or blood sugar occur.

Neural Connectivity and Obesity in Cognitively Normal Adults

Chwa and colleagues (2025) investigated a critical question: Can we detect brain changes due to obesity before someone shows any signs of cognitive decline? Their study, published in npj Dementia, examined body adiposity and neural connectivity in cognitively normal, middle-aged adults.

Even in people with perfectly normal cognitive function, increased body adiposity correlated with measurable reductions in neural connectivity—the strength of communication between different brain regions. Think of your brain as a network of cities; neural connectivity is the quality of the highways connecting them. Obesity was damaging these highways before any cognitive symptoms appeared.

Key Takeaway: Brain changes from obesity are happening silently. You won't feel them occurring. By the time cognitive symptoms appear, significant neural damage may already be underway. This emphasizes the critical importance of early intervention.

What This Means: This research provides a biological mechanism explaining why weight management in your 40s and 50s is such a powerful prevention strategy. Maintaining a healthy weight preserves the neural infrastructure that supports sharp thinking decades later.

The research identified particular vulnerability in regions responsible for memory, executive function, and emotional regulation—precisely the cognitive abilities that decline in dementia.

Long-Term Brain Morphology Changes and Cognitive Impact

Zhang and colleagues (2025) conducted an extensive examination of how long-term obesity impacts brain morphology (physical structure), functional connectivity, and actual cognitive performance in adults.

This research tracked individuals with sustained obesity and documented progressive changes in brain size, white matter integrity, and functional organization. The effects were dose-dependent: the longer someone remained obese, the greater the brain changes.

The study identified specific reductions in grey matter volume—the tissue containing brain cells—and compromised white matter connectivity—the communication pathways between brain regions. Crucially, these structural changes directly correlated with measurable declines in memory, processing speed, and executive function.

Key Takeaway: Obesity causes physical shrinkage and dysfunction of brain tissue. This isn't a temporary or reversible effect after a few months of weight gain; sustained obesity creates lasting architectural changes in your brain.

The Cognitive Consequences: Individuals with longer obesity histories showed measurable impairments in:

Memory consolidation (forming new memories)

Processing speed (how quickly you think)

Executive function (planning, decision-making, impulse control)

The research suggested that earlier intervention—before extensive damage accumulates—preserves more cognitive resilience.

The Genetic Evidence: Causal Relationships Confirmed

Perhaps the most significant study comes from Nordestgaard and colleagues (2026), published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. Using a sophisticated statistical method called Mendelian randomization, these researchers did something revolutionary: they proved that high body mass index causes vascular-related dementia, rather than simply being associated with it.

Throughout medical science, researchers often observe that two things occur together—obesity and dementia, for example—but proving one causes the other is extraordinarily difficult. People who are obese may differ in countless other ways from people who aren't, making it hard to isolate obesity's independent effect.

Mendelian randomization elegantly solves this problem by using genetic variants. Because genes are randomly distributed at birth, comparing people who inherited genes predisposing them to higher BMI against those who didn't essentially creates a "natural experiment" where obesity is the primary difference.

Nordestgaard and colleagues (2026) demonstrated a causal relationship between high body mass index and vascular-related dementia. This isn't correlation; this is causation. Obesity directly causes brain damage through vascular mechanisms.

Key Takeaway: This is the "smoking gun" evidence. The scientific debate is over. Weight gain causes dementia risk through vascular pathways—by damaging the blood vessels supplying your brain.

The research specifically identified vascular dementia—cognitive decline from compromised blood flow—as the primary mechanism. However, obesity's brain-damaging effects extend beyond vascular mechanisms to include inflammation and direct neuronal damage.

Clinical Significance: For healthcare providers and policy makers, this research provides compelling evidence that weight management interventions should be considered primary dementia prevention strategies.

Understanding the Mechanisms: How Does Obesity Damage Your Brain?

Now that we've established the evidence, let's explore the biological pathways through which obesity compromises brain health:

Vascular Dysfunction

Obesity promotes inflammation in blood vessel walls and reduces the production of endothelial-derived nitric oxide, a critical molecule that keeps blood vessels healthy. As vessels stiffen and narrow, blood flow to the brain diminishes. Over years and decades, this chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency starves brain tissue of oxygen and nutrients, leading to vascular dementia.

Systemic Inflammation

Fat tissue, particularly visceral adiposity (fat surrounding organs), acts like an endocrine organ, continuously releasing inflammatory molecules called cytokines and adipokines. These compounds cross the blood-brain barrier and activate microglial cells—brain immune cells that, when chronically activated, damage neural tissue.

Neuroinflammation and Amyloid Accumulation

Chronic neuroinflammation from obesity accelerates the accumulation of amyloid-beta and tau proteins—hallmark pathological features of Alzheimer's disease. Obesity essentially speeds up the molecular processes underlying dementia.

Metabolic Dysfunction

Insulin resistance—a hallmark of metabolic syndrome in obesity—impairs glucose delivery to brain cells. Neurons are extraordinarily energy-dependent, and metabolic disruption directly compromises their function and survival.

Direct Lipotoxicity

Excess adiposity disrupts lipid metabolism, leading to accumulation of toxic lipid intermediates in brain tissue. These lipids directly damage neuronal membranes and mitochondria—the energy-producing structures within cells.

Lifestyle Modifications to Protect Brain Health

Although obesity-related brain changes may begin silently, they are not irreversible—particularly when addressed during midlife. Lifestyle interventions that improve cardiometabolic health also exert direct neuroprotective effects by enhancing cerebral blood flow, reducing neuroinflammation, and restoring insulin signaling in the brain.

Regular physical activity is the most consistently supported intervention. Aerobic exercise improves endothelial function and cerebral perfusion, while resistance training enhances insulin sensitivity and preserves lean mass—both of which are linked to slower brain atrophy and reduced vascular dementia risk. Combining moderate-intensity aerobic exercise with strength training appears more effective than either modality alone.

Dietary quality matters more than calorie restriction alone. Diets emphasizing whole foods, adequate protein, unsaturated fats, and low glycemic load improve metabolic flexibility and reduce systemic inflammation. Mediterranean-style and lower-refined-carbohydrate dietary patterns are associated with better cognitive trajectories, even independent of weight loss.

Sleep optimization plays a critical but often overlooked role. Chronic sleep restriction worsens leptin resistance, elevates cortisol, and impairs glymphatic clearance of neurotoxic metabolites, including amyloid-β. Consistent sleep duration and timing support both metabolic and cognitive resilience.

Stress reduction and social engagement further modulate brain health by lowering sympathetic overactivation and inflammatory signaling. Mindfulness practices, purposeful activity, and cognitive engagement appear to buffer against vascular-related cognitive decline.

Taken together, these interventions reframe lifestyle modification not as cosmetic weight control, but as a core strategy for preserving brain structure, vascular integrity, and long-term cognitive function.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know

Obesity is a Dementia Risk Factor: Multiple independent lines of evidence—from large cohort studies to genetic research—conclusively demonstrate that obesity increases dementia risk.

Brain Damage Happens Early and Silently: Changes in neural connectivity and brain morphology occur in cognitively normal individuals, meaning damage accumulates before symptoms appear.

The Longer You're Obese, the Greater the Damage: Long-term obesity causes progressive, dose-dependent deterioration in brain structure and function.

Weight Management is Dementia Prevention: Maintaining a healthy weight in midlife is one of the most powerful interventions to preserve cognitive function in older age.

Metabolically "Healthy" Obesity Isn't Safe: Even without metabolic complications, adiposity itself damages the brain.

Vascular Pathways Are Key: Vascular-related dementia emerges as a primary mechanism linking obesity to cognitive decline, emphasizing the importance of cardiovascular health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: I'm overweight but feel fine. Should I be concerned about dementia risk?

A: Yes. The research shows that brain changes occur silently before symptoms develop. By the time you notice cognitive changes, significant neural damage may have accumulated. Early intervention preserves more brain resilience.

Q: How much weight loss is needed to benefit brain health?

A: Research suggests that even modest weight loss—5-10% of body weight—can improve vascular function and reduce inflammation. However, achieving a healthy BMI provides the most robust brain protection.

Q: Is it ever too late to benefit from weight loss?

A: The evidence suggests that earlier intervention is preferable because it prevents accumulation of brain damage. However, even in older adults, weight loss improves cognitive outcomes and may slow cognitive decline.

Q: Can exercise alone protect my brain without weight loss?

A: Physical activity has independent benefits for brain health. However, the research specifically highlights the damaging effects of adiposity itself, suggesting that actual weight loss provides distinct advantages beyond exercise's benefits.

Q: What's the relationship between obesity and Alzheimer's disease versus vascular dementia?

A: The research identifies vascular dementia as a primary causal pathway. However, obesity also increases neuroinflammation, which accelerates Alzheimer's pathology. Obesity likely increases risk for both major dementia types through different mechanisms.

Q: Are there medications that can reduce dementia risk if I can't lose weight?

A: While some medications address components of metabolic dysfunction, weight loss remains the most effective intervention. The research emphasizes the specific role of adiposity—the physical fat tissue—in brain damage.

Q: How quickly does cognitive function improve after weight loss?

A: Inflammatory markers and vascular function can improve within weeks. However, reversing brain morphology changes and neural connectivity damage takes longer—typically several months to years. Earlier intervention prevents damage that might not be fully reversible.

Author’s Note

This article was written to synthesize emerging evidence on the relationship between obesity, metabolic health, and brain aging, drawing on peer-reviewed research published between 2024 and 2026. The objective was not merely to summarize individual studies, but to integrate findings from epidemiology, neuroimaging, genetics, and clinical medicine into a coherent, evidence-based narrative with clear clinical and public-health implications.

While the metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of obesity are widely recognized, its neurological effects remain underappreciated in both clinical practice and public discourse. The studies discussed here—including large prospective cohorts, advanced neuroimaging analyses, and Mendelian randomization research—provide converging evidence that excess adiposity is not simply associated with cognitive decline but plays a causal role in vascular-related dementia and structural brain deterioration.

A central theme of this article is timing. Brain changes linked to obesity often develop silently during midlife, years before clinical symptoms emerge. This underscores the importance of early, sustained intervention and reframes weight management as a strategy for preserving cognitive resilience, independence, and quality of life, rather than solely for metabolic or cardiovascular risk reduction.

This content is intended for educational purposes and reflects the current state of scientific knowledge at the time of writing. It should not be interpreted as individualized medical advice. Readers are encouraged to consult qualified healthcare professionals before making significant lifestyle or therapeutic decisions. As the field continues to evolve, interpretations may be refined as new data become available.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Managing Diabesity: A Complete Guide to Weight Loss and Blood Sugar Control | DR T S DIDWAL

Stop the Clock: Proven Ways to Reverse Early Aging if You Have Diabetes | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

5 Steps to Reverse Metabolic Syndrome: Diet, Habit, & Lifestyle Plan | DR T S DIDWAL

Author’s Note

This article was written to synthesize emerging evidence on the relationship between obesity, metabolic health, and brain aging, drawing on peer-reviewed research published between 2024 and 2026. The goal is to translate complex findings from epidemiology, neuroimaging, genetics, and clinical medicine into a clear, evidence-based narrative that is accessible to clinicians, researchers, and health-conscious readers alike.

While the associations between obesity and cardiometabolic disease are well established, the neurological consequences of excess adiposity remain underrecognized in public discourse. The studies discussed herein—including longitudinal cohort analyses, advanced neuroimaging investigations, and Mendelian randomization research—provide converging evidence that obesity is not merely correlated with cognitive decline but plays a causal role in vascular-related dementia and structural brain deterioration.

This article emphasizes prevention and early intervention. Brain changes linked to obesity often develop silently, years before clinical symptoms emerge. Recognizing obesity as a modifiable risk factor for cognitive decline reframes weight management as a strategy for long-term brain preservation, not solely metabolic or cardiovascular health.

The content is intended for educational purposes and should not be interpreted as individualized medical advice. Readers are encouraged to consult qualified healthcare professionals before making significant lifestyle or therapeutic changes. As scientific understanding continues to evolve, interpretations may be refined as new evidence emerges.

References

Chwa, W. J., Rahmani, F., Dolatshahi, M., et al. (2025). Identifying obesity and dementia risk: Body adiposity and neural connectivity in cognitively normal, mid-life adults. npj Dementia, 1, 24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44400-025-00028-w

Nordestgaard, L. T., Luo, J., Emanuelsson, F., Leyden, G., Sanderson, E., Davey Smith, G., Christoffersen, M., Afzal, S., Benn, M., Nordestgaard, B. G., Tybjærg-Hansen, A., & Frikke-Schmidt, R. (2026). High body mass index as a causal risk factor for vascular-related dementia: A Mendelian randomization study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, dgaf662. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaf662

Visseren, F. L. J., Mach, F., Smulders, Y. M., Carballo, D., Koskinas, K. C., Bäck, M., Benetos, A., Biffi, A., Boavida, J.-M., Casper, D., Čelutkienė, J., Cosentino, F., Deaton, C., Hansen, J. B., Mellbin, L. G., Sanz, G., Seferović, P. M., Shlyakhto, E. V., Simpson, I. A., & Williams, B. (2024). The global burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis, 391, 117404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117404

Wang, M., Yu, L., Tong, Z., Sun, G., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., Xing, X., Zhao, J. V., Zhang, X., & Yang, X. (2026). Obesity, metabolic health, and brain health: Insights from a prospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 392, 120184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.120184

Zhang, D., Shen, C., Chen, N., et al. (2025). Long-term obesity impacts brain morphology, functional connectivity and cognition in adults. Nature Mental Health, 3, 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00396-5