The 9-Year Healthspan Gap: Living Longer, Not Better

Are you adding years to life—or life to years? Learn why a 9-year health gap exists and how to extend your functional lifespan.

AGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/22/202616 min read

Lifespan vs. Healthspan vs. Longevity

We are living through a paradox of modern medicine. Global life expectancy has risen dramatically over the past century, fueled by advances in sanitation, vaccines, cardiovascular therapies, and cancer treatment. Yet beneath this success lies a quieter and more troubling reality: we are adding years to life faster than we are adding life to years. The distinction between lifespan, healthspan, and longevity is no longer semantic—it is structural, economic, and deeply personal.

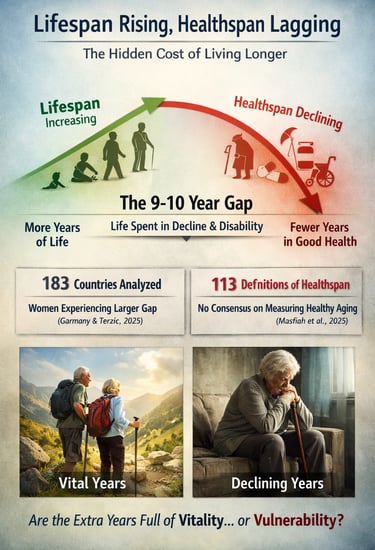

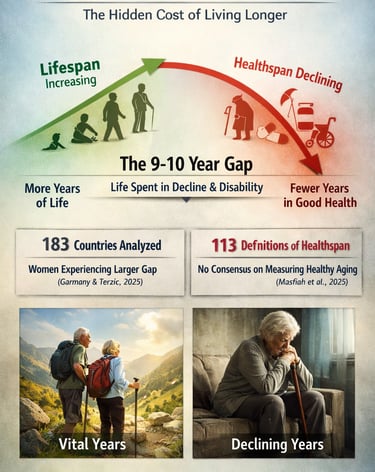

A growing body of research shows that the average person now spends nearly a decade of life managing chronic disease, disability, or functional decline before death. A comprehensive global analysis across 183 countries found a 9–10 year healthspan–lifespan gap, with women experiencing an even wider divide (Garmany & Terzic, 2025). This means that while survival curves continue to improve, functional capacity, independence, and quality of life are not keeping pace.

Compounding the challenge, a 2025 systematic review identified 113 competing definitions of healthspan, revealing a profound lack of consensus in how we measure healthy aging (Masfiah et al., 2025). Without standardized metrics, progress becomes difficult to track and even harder to achieve. As Olshansky (2018) argued, the goal of modern medicine should shift from extending biological survival to optimizing the years lived in good health.

The future of aging science does not hinge on how long we live. It hinges on whether those additional years are defined by vitality—or vulnerability.

Clinical pearls

1. Functional Trajectory vs. Disease Snapshots

Scientific Perspective: Chronic diseases often share underlying biological drivers (senescence, inflammation). Instead of treating "Diabetes" or "Arthritis" in isolation, research suggests monitoring the rate of functional decline (e.g., gait speed, grip strength) as a proxy for biological age.

Don’t just ask "Is my blood sugar okay?" Ask, "How is my physical capacity trending compared to last year?" Shifting focus to function allows you to notice "pre-frailty" long before a clinical diagnosis occurs.

2. The "9-Year Gap" Awareness

Scientific Perspective: Garmany & Terzic (2025) highlight that we are "over-living" our health by nearly a decade. Medical success should no longer be measured by delayed mortality but by compression of morbidity (keeping the period of illness as short as possible at the very end of life).

Living to 90 is a hollow victory if the last 10 years are spent in a nursing home. Your goal for every intervention (medication or lifestyle) should be: "Will this help me stay independent longer?"

3. Exercise as "Healthspan Insurance"

Scientific Perspective: While medicine is excellent at extending lifespan (keeping a failing heart beating), exercise is the most effective tool for extending healthspan. It acts on almost every "Hallmark of Aging," particularly mitochondrial function and proteostasis.

Think of exercise not as weight loss, but as a fountain of youth medicine. It has a modest effect on how many years you live, but a massive effect on how well you live those years. It is the difference between climbing stairs at 80 and needing a lift.

4. The Measurement Paradox (The "113 Definitions" Problem)

Scientific Perspective: Because there are 113 different definitions of healthspan (Masfiah et al., 2025), clinicians cannot rely on a single "Healthspan Score" We must use composite metrics, including biomarkers (like Cystatin C or NT-proBNP) and functional tests.

There is no single "Longevity Test" you can buy online that tells the whole story. Your healthspan is a mosaic. It’s a combination of your labs, your mood, your cognitive clarity, and your physical strength.

5. Social Connection as a Biological Buffer

Scientific Perspective: Loneliness acts as a chronic stressor that accelerates "inflammaging" (age-related systemic inflammation). High-quality social engagement is correlated with lower levels of IL-6 and CRP, markers that predict a shorter healthspan.

Isolation is as toxic as smoking. Maintaining a sense of purpose and a social circle isn't just "feel-good" advice; it is a biological necessity that protects your brain and heart from aging faster than they should.

6. The Gender Health-Survival Paradox

Scientific Perspective: Women generally have a longer lifespan but a shorter proportional healthspan than men (Garmany & Terzic, 2025). They live longer but often with more years of disability/frailty, partly due to post-menopausal hormonal shifts and lower baseline muscle mass.

Because you are likely to live longer, you must be even more aggressive about strength training and bone density early on. You are preparing for a "longer marathon," which requires more structural maintenance to avoid a decade of frailty.

Defining the Terms: A Primer

Lifespan

Lifespan is the most straightforward of the three terms. It is the total number of years an individual lives from birth to death, measured at the population level as life expectancy. It is objective, binary, and easily measurable. You are either alive or you are not. This simplicity makes it an appealing metric for governments and researchers, but it tells us nothing about the quality of those years.

Healthspan

Healthspan refers to the period of life spent in good health, free from significant chronic disease or disability. It is, conceptually, the answer to the question that actually matters. But here is where the science gets complicated. A systematic review by Masfiah et al. (2025) searched the literature and found 113 different published definitions of healthspan. Some researchers mark the end of healthspan at the diagnosis of the first chronic disease. Others focus on functional capacity, asking whether a person can climb stairs, manage finances, or live independently. Still others incorporate biomarkers, quality of life questionnaires, psychological well-being, or composite frailty indices.

This lack of consensus is not merely inconvenient. Without a universally accepted metric, we cannot reliably compare interventions, track population trends, or allocate resources optimally. As Kaeberlein (2018) warned in a conceptual critique in GeroScience, the healthspan concept, while compelling, risks becoming scientifically meaningless if it cannot be operationalized with rigor.

Longevity

Longevity is perhaps the most misunderstood term of all. Historically, it was used interchangeably with lifespan. Increasingly, however, longevity in scientific and clinical contexts refers to the achievement of exceptional age while maintaining health and function. In the emerging field of longevity medicine, the goal is explicitly to extend the healthy years of life rather than simply to delay death. This semantic evolution matters because it reshapes what we are trying to optimize.

The 9-Year Gap That Demands Our Attention

Once the distinctions between lifespan and healthspan are clear, a disturbing reality comes into focus: these two quantities are diverging. Medical advances are extending the total number of years people live, but they are not extending the healthy years at the same rate. The result is a growing period of life spent managing chronic illness, experiencing functional decline, and navigating an increasingly costly healthcare system.

The most comprehensive quantification of this problem comes from Garmany and Terzic (2025), who analyzed data from all 183 World Health Organization member states published in Communications Medicine. Their findings reveal that globally, the average person experiences a gap of 9 to 10 years between their total lifespan and their healthspan. For women, this gap is even wider. This is not a statistical abstraction. It represents nearly a decade of life spent not thriving.

What makes this analysis particularly powerful is its regional granularity. The gap is not uniform across the globe. It differs in both magnitude and in the specific diseases that drive it depending on geography. Some regions have achieved meaningful compression of morbidity, keeping the period of significant illness relatively short relative to total lifespan. Others have seen the gap widen. These regional differences, the authors argue, are not random. They reflect differences in healthcare systems, economic resources, cultural factors, dietary patterns, and public health infrastructure, all of which are potentially modifiable.

Key Statistic

A global analysis of 183 WHO member states found a 9 to 10 year average gap between total lifespan and healthspan. Women experience an even larger gap than men (Garmany & Terzic, 2025).

Why the Confusion Has Real Consequences

On a personal level, the confusion between these terms can lead people to make health decisions optimized for the wrong outcome. Exercise, for example, adds only modest years to average life expectancy, but its impact on functional capacity, cognitive performance, mood, and quality of life in later decades is profound. Social engagement and a sense of purpose show similar patterns: modest effects on mortality but substantial effects on how well the later years are experienced.

Asking your physician not just about your disease risk but about your functional trajectory is a genuinely different and more useful question. It shifts the conversation from preventing death to maintaining the ability to live fully.

The Measurement Crisis at the Heart of Healthspan Science

The 113 definitions problem identified by Masfiah et al. (2025) is not merely an inconvenience. It is a scientific crisis. Without standardized, validated, culturally sensitive metrics for healthspan, progress in this field will remain difficult to assess and even harder to achieve.

Current approaches to measuring healthspan include the onset of the first chronic disease, scores on activities of daily living, health-adjusted life expectancy calculations, composite frailty indices, self-reported health status, biomarker panels, and newer tools such as pace-of-aging metrics. Each captures something real, but they do not all capture the same thing. A person scoring as healthy by one metric may score as declining by another.

The global scope of the challenge makes this harder still. As Garmany and Terzic (2025) emphasize, their regional analysis demonstrates that what constitutes healthy aging cannot be evaluated against a single universal standard. Health expectations, functional norms, and the healthcare resources available to support aging populations vary dramatically across the world. Any standardized metric must somehow account for this diversity while still enabling meaningful comparisons.

The Healthy Longevity Challenge: A Systems Perspective

Von Blanquet (2025), writing in Innovations in Healthcare and Outcome Measurement, frames the healthspan-lifespan gap as a systems challenge rather than a purely biological one. Closing this gap requires not just better medicines but better systems: healthcare delivery models that are organized around maintaining function and quality of life across the full arc of aging, not merely around treating disease episodes.

This framing has important implications for how we think about investment and innovation. Medical breakthroughs that extend life without improving its quality may be less valuable than lower-technology interventions that maintain function, support independence, and preserve social engagement. The challenge for healthcare systems is to develop outcome measurement frameworks that can capture these differences and direct resources accordingly.

Using Physical Activity to Promote Lifelong Health and Well-Being

Dev Roychowdhury’s 2020 commentary discusses how regular physical activity contributes to improved health outcomes throughout the life span. The paper highlights that physical activity — defined as any bodily movement requiring energy expenditure — is strongly linked with positive psychological, physical, and social outcomes, yet a large proportion of the global population remains inactive or sedentary, increasing risks for chronic disease and mortality. Across age groups, activity supports cardiovascular health, bone development, cognitive function, emotional well-being, and social development in children, while in adults and older adults, it is associated with reduced risk of chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, hypertension), better metabolic health, improved muscular strength, and slower cognitive decline. The review also examines gender differences in activity patterns and benefits, discusses advantages for atypical populations (including those with chronic conditions), and underscores the role of lifestyle factors in shaping physical function and participation. Roychowdhury calls for tailored interventions and further research to identify motivational and contextual influences on physical activity engagement and adherence.

Key Takeaway from Each Study

The table below summarizes the single most important insight from each of the primary studies informing this discussion.

Jugran (2025) – Journal of Global Health

Extending lifespan without improving healthspan is a policy failure. The primary goal of health systems must shift toward ensuring that added years are lived in good health, not merely in biological survival.

Garmany & Terzic (2025) – Communications Medicine

The healthspan-lifespan gap varies significantly by world region in both magnitude and disease composition, proving that the gap is not inevitable and can be narrowed through targeted, regionally informed interventions.

von Blanquet (2025) – Springer Innovations in Healthcare

Closing the healthspan-lifespan gap is a systems challenge requiring redesigned healthcare delivery models focused on functional outcomes and quality of life, not only disease treatment.

Garmany et al.(2021) – npj Regenerative Medicine

A 9-year average global gap between lifespan and healthspan represents one of the most significant unaddressed challenges in modern medicine, with profound implications for healthcare costs and individual well-being.

Masfiah et al. (2025) – Ageing Research Reviews

The existence of 113 different published definitions of healthspan is a fundamental scientific problem that must be resolved through consensus standardization before meaningful progress in the field can be reliably measured.

The Path Forward: What the Science Demands

1. We Won the Survival Battle—But Not the Aging War

Over the past century, medicine has dramatically increased life expectancy. Vaccination, cardiovascular therapeutics, oncology advances, and public health infrastructure transformed survival curves. But survival is a blunt instrument. A growing body of global evidence shows that extended lifespan has not been matched by proportional gains in healthspan—the years lived free from significant chronic disease and disability. A comprehensive multi-country analysis reported a 9–10 year healthspan–lifespan gap, with women experiencing an even wider divide (Garmany & Terzic, 2025). The uncomfortable truth: we are living longer, but not necessarily living better.

2. Words Shape Incentives—And Incentives Shape Outcomes

The interchangeable use of lifespan, healthspan, and longevity distorts priorities. When mortality reduction becomes the primary endpoint, interventions that prolong survival—even with increased frailty—can appear successful. As argued in JAMA, the mission of modern medicine should shift from merely adding years to adding life to years (Olshansky, 2018). Language determines what we measure; what we measure determines what we reward; and what we reward determines what we scale.

3. The Measurement Crisis in Healthspan Science

Unlike death, health is multidimensional. A 2025 systematic review identified 113 different definitions of healthspan, spanning disease onset, functional metrics, frailty indices, biomarkers, and self-reported quality of life (Masfiah et al., 2025). Without standardized, validated metrics, comparisons across studies and regions become unreliable. This fragmentation slows policy reform, complicates trial design, and obscures true progress.

4. The Economic Consequences of Misaligned Metrics

Extending lifespan without extending healthspan compounds healthcare costs. Additional years marked by multimorbidity translate into higher medication burdens, hospitalizations, long-term care dependency, and caregiver strain. As emphasized in Journal of Global Health, celebrating longevity gains without addressing functional decline represents a policy failure (Jugran, 2025). Health systems optimized for episodic disease treatment are ill-equipped for prolonged frailty.

5. The Gender Gap We Can No Longer Ignore

Women consistently outlive men, yet spend a greater proportion of later years managing disability and chronic illness. The gendered expansion of morbidity raises urgent biological, social, and healthcare access questions (Garmany & Terzic, 2025). Longevity equity must mean not just longer survival, but proportionate preservation of vitality.

6. Physical Activity Across the Life Span

Roychowdhury (2020) highlights that regular physical activity improves physical, psychological, and social health at every stage of life. It reduces chronic disease risk, enhances cognitive function, and supports emotional well-being. The paper emphasizes tailored interventions to increase participation and long-term adherence across diverse populations.

7. From Mortality Endpoints to Functional Endpoints

The emerging field of geroscience argues that targeting the biological mechanisms of aging may simultaneously delay multiple chronic diseases (Seals et al., 2016). But translation requires redefining trial endpoints. Functional capacity, cognitive performance, and independence must be elevated alongside survival metrics. A therapy that extends life but accelerates frailty is not progress—it is postponement.

8. A Systems-Level Redesign

Closing the healthspan–lifespan gap is not solely a biomedical challenge; it is a systems challenge. Healthcare delivery models must pivot toward preserving functional independence, mobility, cognition, and social engagement across the lifespan. Regional variation in the global gap demonstrates that morbidity compression is achievable, not mythical (Garmany & Terzic, 2025). The blueprint exists—we must align incentives to follow it.

9. The Defining Question of Our Era

The central question of 21st-century medicine is not, “How long can humans live?” It is, “How long can humans remain capable, independent, and engaged?” The future of longevity science will be judged not by survival curves alone, but by whether extended years remain years worth living.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What is the simplest way to understand the difference between lifespan, healthspan, and longevity?

Lifespan is how long you live in total. Healthspan is how many of those years you spend in good health, free from significant chronic disease or disability. Longevity increasingly refers to the goal of achieving a long life while maintaining health and function, rather than simply surviving to an advanced age. You can have a long lifespan but a short healthspan if your final decade is spent managing serious illness.

Q2. Why does a 9 to 10 year healthspan-lifespan gap matter?

It means the average person globally spends roughly a decade of their life in poor health before death. This is not inevitable. Research shows significant regional variation in the size of this gap, indicating that the right combination of lifestyle choices, healthcare delivery, and public health policy can compress this period of morbidity. The gap also represents an enormous economic burden on healthcare systems, families, and governments.

Q3. Why is healthspan so difficult to measure?

Unlike lifespan, which has a single, objective endpoint, healthspan is multidimensional. It incorporates biological markers, physical function, cognitive capacity, and subjective quality of life. Cultural context matters too: what constitutes good health varies across populations. A systematic review by Masfiah et al. (2025) found 113 different published definitions, reflecting the lack of scientific consensus. Without standardized metrics, comparing studies and tracking progress remain difficult.

Q4. Why do women experience a larger healthspan-lifespan gap than men?

Women generally live longer than men but do not spend proportionally more years in good health. This means the additional years of life women gain tend to come with higher rates of chronic disease, disability, and frailty. Garmany and Terzic (2025) documented this gender disparity across their global analysis. The biological, social, and healthcare system factors driving this difference are an active area of research.

Q5. Can individual lifestyle choices actually narrow the healthspan-lifespan gap?

Yes. Evidence consistently supports the role of regular physical activity, dietary quality, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation in extending the healthy years of life. Physical exercise may add modest years to total lifespan but has a disproportionately large effect on functional capacity and quality of life in later decades. Dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet have shown associations with delayed frailty and reduced disability in older adults. These are not guarantees, but they are among the most powerful levers individuals can act on.

Q6. What should I ask my doctor to focus more on healthspan?

Ask about your functional trajectory, not just your disease risk. Useful questions include: How are my physical function and cognitive markers trending compared to my age group? What interventions would best preserve my independence and quality of life as I age? Are we optimizing for my functional outcomes, not just for preventing specific diseases? These questions shift the clinical conversation from disease management toward the preservation of healthy function.

Q7. What changes are needed at the policy level to close the healthspan-lifespan gap?

Garmany and Terzic (2025) call for health-centric system reform and region-informed policies that go beyond life expectancy as the primary metric of population success. This means investing in preventive care that maintains function, redesigning healthcare delivery around outcomes that matter to patients across the full arc of aging, and developing standardized healthspan metrics that can track progress at the population level. The regional variation documented in their analysis provides a practical evidence base for designing these interventions.

To help your readers move from theory to practice, here is a structured Healthspan Audit. This checklist is designed to be used during a routine physical or a dedicated longevity consultation, bridging the gap between clinical data and personal action.

The Healthspan Audit: A Personal Assessment

Use this checklist to evaluate where you stand in the 9-year healthspan gap and identify areas for "morbidity compression."

1. Functional & Physical Capacity

Maintaining the "structural integrity" of the body is the primary defense against the gendered frailty gap.

Grip Strength: Is your grip strength within the top 25% for your age/gender? (A powerful proxy for all-cause mortality).

Gait Speed: Can you comfortably walk at a brisk pace (approx. 1 meter/second)?

Stability: Can you stand on one leg for 10+ seconds with eyes open? (Predictive of fall risk in later decades).

V02 Max: Have you had your cardiorespiratory fitness tested? (The strongest predictor of longevity).

2. Metabolic & Biological Markers

Move beyond "normal" ranges toward "optimal" longevity ranges.

Glycemic Variability: Are you tracking Hba1c or using a CGM to monitor glucose spikes?

Inflammatory Burden: Have you checked hs-CRP? (Monitoring "inflammaging").

Lipid Quality: Looking at ApoB rather than just total cholesterol.

Organ Reserve: Checking Cystatin C (for kidney health) or NT-proBNP (for heart stress).

3. Cognitive & Psychological Reserve

Protecting the "software" of the brain is as vital as the "hardware" of the body.

Cognitive Baseline: Have you performed a baseline screening (like a MoCA) to track changes over time?

Social Frequency: Do you have at least 3 deep social connections you interact with weekly?

Sense of Purpose: Can you clearly articulate your "Ikigai" or reason for being? (Correlated with lower cortisol and higher healthspan).

Sleep Hygiene: Are you consistently achieving 7–9 hours of sleep with adequate REM and Deep sleep stages?

4. Environmental & System Factors

Closing the gap by optimizing your "ecosystem."

Medication Audit: Are you on "longevity-neutral" or "longevity-positive" medications? (Reviewing polypharmacy with your doctor).

Nutrient Density: Is your diet focused on fibre-rich, high-protein, Mediterranean-style patterns?

Resistance Training: Are you performing at least 2 sessions of heavy load-bearing exercise per week?

Author’s Note

The distinction between lifespan, healthspan, and longevity is more than a semantic exercise—it reflects a shift in how we define progress in medicine. For decades, extending survival was the primary benchmark of success. And by that measure, modern healthcare has achieved extraordinary gains. Yet as the evidence increasingly shows, longer life does not automatically translate into better life.

This article was written to clarify terminology that is often used interchangeably in public discourse but carries distinct scientific and policy implications. The growing documentation of a global healthspan–lifespan gap, the absence of consensus around healthspan measurement, and the regional variability in aging outcomes suggest that the next frontier in medicine is not merely preventing death but preserving function.

My goal here is not to diminish the value of longevity research, but to sharpen its focus. If we fail to define what we mean by healthy aging, we risk optimizing for the wrong endpoint. The central question is not simply, “How long can we live?” but “How long can we live well?”

As clinicians, researchers, policymakers, and individuals, we must align our language with our values. When we prioritize functional independence, cognitive vitality, and quality of life, we reshape the incentives that guide research funding, healthcare delivery, and personal decision-making.

The future of aging science will not be judged by survival curves alone. It will be judged by whether the added years are worth living.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Living to 100: Is it Genetics or Lifestyle? What the New Science Says | DR T S DIDWAL

Time-Restricted Eating: Metabolic Advantage or Just Fewer Calories? | DR T S DIDWAL

Can You Revitalize Your Immune System? 7 Science-Backed Longevity Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise and Longevity: The Science of Protecting Brain and Heart Health as You Age | DR T S DIDWAL

Light and Longevity: Can Sunlight Slow Cellular Aging? | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Crimmins, E. M. (2015). Lifespan and healthspan: Past, present, and promise. The Gerontologist, 55(6), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv130

Garmany, A., Yamada, S., & Terzic, A. (2021). Longevity leap: Mind the healthspan gap. npj Regenerative Medicine, 6, Article 57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41536-021-00169-5

Garmany, A., & Terzic, A. (2025). Healthspan-lifespan gap differs in magnitude and disease contribution across world regions. Communications Medicine, 5, Article 381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01111-2

Jugran, D. K. (2025). Too well to die; too ill to live: An update on the lifespan versus healthspan debate. Journal of Global Health, 15, Article 03022. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.15.03022

Kaeberlein, M. (2018). How healthy is the healthspan concept? GeroScience, 40, 361–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-018-0036-9

Masfiah, S., Kurnialandi, A., Meij, J. J., & Maier, A. B. (2025). Definitions of healthspan: A systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews, 111, Article 102806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2025.102806

Olshansky, S. J. (2018). From lifespan to healthspan. JAMA, 320(13), 1323–1324. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12621

Seals, D. R., Justice, J. N., & LaRocca, T. J. (2016). Physiological geroscience: Targeting function to increase healthspan and achieve optimal longevity. The Journal of Physiology, 594(8), 2001–2024. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282665

von Blanquet, H. M. (2025). The healthy longevity challenge: Closing the gap between lifespan and healthspan. In P. Plugmann & D. Portius (Eds.), Innovations in healthcare and outcome measurement. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-77302-0_10

Roychowdhury D. (2020). Using Physical Activity to Enhance Health Outcomes Across the Life Span. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk5010002SUMMARIZE