Obesity and Fatty Liver Disease: What Science Says About Risk and Health

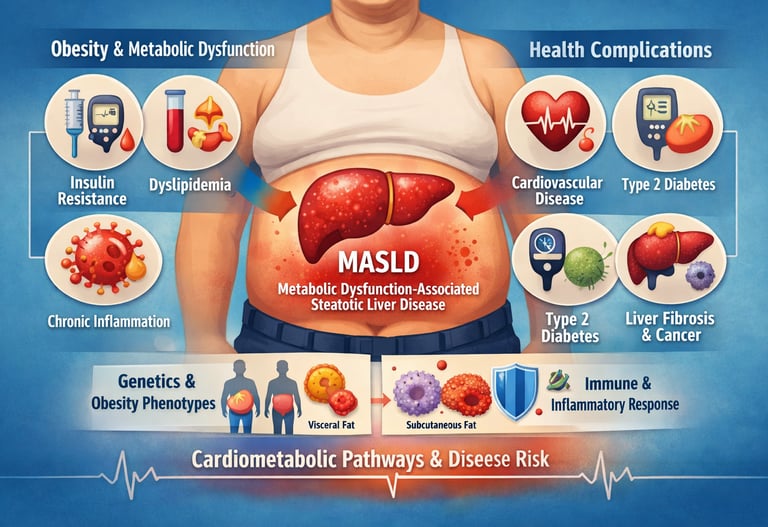

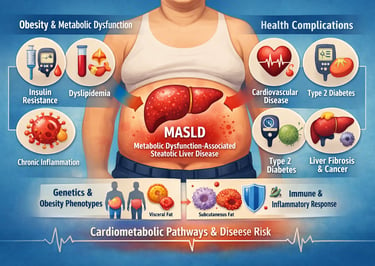

Discover how obesity contributes to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and impacts overall health. Learn what recent scientific research reveals about risk factors, liver health, cardiometabolic complications, and strategies for prevention and management.

OBESITY

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/2/202610 min read

The global health landscape is currently grappling with an unprecedented rise in obesity, a condition that now affects more than 40% of adults in many developed nations. However, contemporary scientific understanding has shifted away from viewing obesity merely as a matter of body weight. Instead, recent research from 2025 and 2026 highlights a complex interplay between adipose tissue, systemic inflammation, and organ-specific complications. Central to this evolution is the emergence of Metabolical Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD), a condition formerly known as NAFLD, which serves as a critical indicator of an individual's true metabolic health.

Recent studies emphasize that the progression from obesity to severe disease is dictated by "competing cardiometabolic pathways" (Hirooka et al., 2026). This suggests that while two individuals may share the same Body Mass Index (BMI), their biological trajectories—ranging from liver scarring to cardiovascular events—can differ wildly based on their unique obesity phenotype (Choe et al., 2025). Furthermore, the long-debated concept of "metabolically healthy obesity" is being scrutinized; evidence now suggests that liver dysfunction often develops silently even in the absence of traditional markers like high blood sugar (Koliaki et al., 2025). By examining the synergistic relationship between fat distribution, immunometabolism, and lipid profiles, we can better understand why obesity remains a primary predictor of life-threatening conditions like atherogenic dyslipidemia (Fotros et al., 2026). This article explores how these cutting-edge insights are transforming personalized medicine and clinical intervention

.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Location over Load" Principle

Research into obesity phenotypes confirms that visceral adipose tissue (VAT)—fat stored around internal organs—is a significantly stronger driver of atherogenic dyslipidemia than subcutaneous fat (Choe et al., 2025).

Your waistline matters more than your weight. Even if the scale doesn't move, losing "belly fat" specifically can dramatically lower your risk of a heart attack by improving your blood fat levels.

2. MASLD as a Silent Metabolic Sentinel

The presence of Metabolically Dysfunctional-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) is often the first objective sign that "metabolically healthy obesity" is transitioning into systemic disease (Koliaki et al., 2025).

Don't be fooled by "normal" blood sugar levels. A liver ultrasound or FibroScan can reveal hidden health risks years before diabetes or heart disease show up on a standard blood test.

3. The Cardiovascular "Synergy" of Obesity

Obesity and MASLD do not just add to cardiovascular risk; they act synergistically to create atherogenic dyslipidemia, characterized by high triglycerides and small, dense LDL particles (Fotros et al., 2026).

If you have both obesity and a fatty liver, your heart risk isn't just "double"—it’s compounded. You need a proactive heart-health plan that goes beyond just watching your cholesterol.

4. Inflammation is a "Double-Edged Sword"

Immunometabolism research shows that not all obesity-related inflammation is destructive; some pathways are essential for tissue repair and infection defense (Lee, 2026).

The goal isn't to "kill" inflammation with supplements, but to balance it. Healthy habits like exercise help switch your body from "bad" chronic inflammation to "good" protective immune responses.

5. Genetic and Biological "Competing Pathways"

Individual biological trajectories determine whether obesity leads to MASLD; different patients follow different cardiometabolic pathways based on their unique cellular responses (Hirooka et al., 2026).

Stop comparing your progress to others. Your body has its own unique "roadmap" for handling fat. Personalized medicine—treatments tailored to your specific metabolic type—is more effective than a one-size-fits-all diet.

Why Obesity and Liver Health Matter More Than Ever

Obesity has become one of the most pressing health challenges of our time, affecting over 40% of the adult population in many developed nations. But obesity isn't just about body weight—it's deeply connected to how our bodies metabolize nutrients, produce energy, and respond to inflammation. One of the most significant discoveries in recent metabolic research is the link between obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

The Competing Cardiometabolic Pathways of Obesity and MASLD

Hirooka and colleagues recently published groundbreaking work in Gastro Hep Advances examining how competing cardiometabolic pathways shape the relationship between obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Their research suggests that obesity doesn't follow a single pathway toward disease—instead, different biological mechanisms compete, determining whether someone develops serious liver problems or manages their weight with fewer complications.

The study challenges the oversimplified view that all obesity leads to the same health outcomes. Instead, individual variation in how the body handles fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and inflammation means some people develop severe MASLD while others with similar body weight remain relatively protected. This finding is crucial because it suggests personalized medicine approaches—rather than one-size-fits-all treatment—may be the future of obesity and liver disease management.

Understanding these competing pathways could help clinicians predict who needs more aggressive intervention and who might respond better to lifestyle modifications alone. It also opens doors to developing targeted therapies that interrupt the specific pathway someone is following toward disease.

Obesity as a Predictor of Atherogenic Dyslipidemia in MASLD Patients

In a study published in Scientific Reports, researchers Fotros, Hekmatdoost, and Yari (2026) investigated a specific complication many MASLD patients face: atherogenic dyslipidemia. This condition refers to abnormal blood fat profiles that specifically increase the risk of atherosclerosis—the narrowing and hardening of arteries—and cardiovascular disease.

Their findings demonstrate that obesity is a significant predictor of atherogenic dyslipidemia in people with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. In other words, heavier patients with MASLD were more likely to have dangerous blood lipid patterns that increase heart attack and stroke risk.

The research reveals a dangerous "double trouble" scenario: individuals with both obesity and MASLD face compounded cardiovascular risk. The combination doesn't just add risks together—it creates a synergistic effect where the dyslipidemia (abnormal blood fats) becomes more severe and more resistant to treatment.

This finding underscores why cardiovascular monitoring is essential for anyone diagnosed with MASLD. Weight loss interventions that target both cardiometabolic health and liver function may be necessary for this high-risk population.

Metabolically Healthy Obesity vs. MASLD: Navigating the Controversy

Published in Current Obesity Reports, this comprehensive review by Koliaki and colleagues tackles one of metabolic medicine's most controversial questions: Can someone be metabolically healthy obese? The researchers examined whether metabolically healthy obesity actually represents a genuine condition or a temporary state before metabolic dysfunction develops.

Their analysis of multiple studies reveals that while some obese individuals may not initially show traditional metabolic dysfunction markers (like insulin resistance or abnormal blood sugar), many eventually progress to MASLD and metabolic problems. The presence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease appears to be a critical marker distinguishing truly "healthy" obesity from at-risk obesity.

The concept of risk-free obesity is largely a myth. Even individuals classified as "metabolically healthy obese" show signs of disease progression, particularly in the liver. This suggests that body weight itself—independent of traditional metabolic markers—represents a risk factor that shouldn't be ignored.

If you're obese but feel metabolically healthy, this research suggests regular liver screening and metabolic monitoring remain important. The absence of current disease doesn't guarantee future protection.

Obesity Phenotypes and Atherogenic Dyslipidemias: Not All Obesity Is Alike

Published in the European Journal of Clinical Investigation, Choe and international colleagues explored an important concept: obesity phenotypes—the idea that obesity manifests differently in different people based on genetics, lifestyle, and metabolic factors. Their research demonstrated that certain obesity phenotypes have much stronger associations with atherogenic dyslipidemia than others.

The study identified that visceral obesity (fat stored around organs) and certain metabolic profiles create more dangerous dyslipidemia patterns than subcutaneous obesity (fat under the skin). This distinction matters tremendously for cardiovascular risk prediction.

Where your body stores fat matters as much as how much fat you carry. Two people with identical body weights can have vastly different cardiovascular and metabolic risks depending on their obesity phenotype. Measuring waist circumference and understanding fat distribution may be more predictive of dyslipidemia risk than BMI alone.

This research supports the use of body composition analysis (like waist-to-hip ratios and imaging studies) alongside traditional weight measurements for comprehensive health assessment.

Immunometabolism in Obesity: The Inflammation Connection

Lee's recent work in PLoS Biology explores immunometabolism—the intersection between immune system function and metabolic health. The research reveals that obesity triggers chronic inflammation through multiple immune system mechanisms, but interestingly, some inflammatory responses are actually beneficial while others are detrimental.

Lee's analysis shows that obesity-related inflammation can be both protective (fighting infections and initiating repair) and destructive (driving insulin resistance, MASLD development, and atherosclerosis). The balance between beneficial and harmful inflammation determines disease severity.

Understanding inflammation in obesity isn't about eliminating it entirely—it's about promoting beneficial inflammatory responses while controlling the harmful ones. This nuanced view opens possibilities for therapies that modulate rather than simply suppress immunity.

Traditional anti-inflammatory approaches might inadvertently suppress beneficial immune responses. This research suggests future treatments should be designed to promote metabolic health while preserving protective immunity—a more sophisticated approach than current strategies.

Synthesis: How These Research Findings Connect

These five studies, spanning 2025-2026, paint a comprehensive picture of obesity and metabolic dysfunction:

The Big Picture: Obesity is not a monolithic condition. Rather, it involves competing biological systems, diverse metabolic phenotypes, and complex immune responses. Whether someone develops severe MASLD, dangerous atherogenic dyslipidemia, or remains relatively protected depends on their specific metabolic pathway, obesity phenotype, and immunometabolic status.

Clinical Implications: Healthcare providers should move beyond simple BMI-based assessments toward comprehensive evaluations that include:

Liver function and imaging screening

Blood lipid panel assessment

Visceral vs. subcutaneous fat evaluation

Inflammatory biomarker testing

Personalized risk stratification based on metabolic phenotype

Action Plan for Prevention and Management of Obesity and MASLD

Regular Screening & Monitoring

Get periodic liver imaging (ultrasound, FibroScan) and blood tests for liver enzymes, glucose, and lipid profiles.

Track BMI, waist circumference, and body composition to identify visceral fat accumulation early.

Personalized Nutrition & Weight Management

Focus on balanced, calorie-appropriate diets rich in vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains.

Reduce added sugars, refined carbs, and saturated fats to lower liver fat and improve lipid profiles.

Consider personalized dietary plans based on metabolic phenotype (visceral vs subcutaneous fat).

Regular Physical Activity

Combine aerobic exercise (150 minutes/week) with resistance training 2–3 times/week.

Exercise improves insulin sensitivity, reduces visceral fat, and helps modulate inflammation

.

Inflammation Management

Encourage healthy lifestyle habits (sleep, stress reduction, exercise) to promote protective immune responses.

Avoid excessive anti-inflammatory supplements that may suppress beneficial inflammation.

Cardiometabolic Risk Reduction

Monitor and manage blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels.

Collaborate with healthcare providers for medications if lifestyle measures alone are insufficient

.

Regular Follow-up & Personalized Care

Develop a long-term management plan with your clinician, tailored to your unique metabolic pathways and obesity phenotype.

Reassess risk factors periodically and adjust interventions as needed.

Key Blood Markers & Diagnostic Thresholds (2026 Standards)

ALT (Alanine Aminotransferase) – The Inflammation Marker

Traditional Range: Often cited as up to 40 U/L.

2026 Research Threshold: Risk is now identified at >30 U/L for men and >19 U/L for women.

Scientific Insight: Higher levels within the "normal" range often mask silent liver inflammation (Hirooka et al., 2026).

AST (Aspartate Aminotransferase) & The AST:ALT Ratio

Threshold: An AST:ALT ratio < 1 is typical in early MASLD.

Scientific Insight: If AST begins to exceed ALT (Ratio > 1), it may signal the transition from simple fat accumulation to advanced liver scarring or fibrosis.

Triglycerides – The Fuel for Dyslipidemia

Threshold: ≥ 150 mg/dL.

Scientific Insight: High triglycerides are a core diagnostic criterion for MASLD and are the primary driver of the "double trouble" cardiovascular risk (Fotros et al., 2026).

HDL Cholesterol – The Protective Marker

Threshold: < 40 mg/dL (Men) or < 50 mg/dL (Women).

Scientific Insight: Low HDL is a hallmark of the "atherogenic phenotype," which Choe et al. (2025) identified as a critical predictor of heart disease in obese patients.

FIB-4 Index – The Fibrosis Predictor

Threshold: Score > 1.3.

Scientific Insight: This is a calculated score using age, AST, ALT, and Platelets. It is now the preferred primary screening tool to determine if a patient needs a FibroScan.

Important Clinical Context

The "Normal" Trap: Up to 50% of MASLD patients present with "normal" liver enzymes. The 2026 guidelines suggest that if you have a high waist circumference, you should be screened regardless of blood work.

TyG Index: Clinicians are increasingly using the Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) Index as a more sensitive measure of insulin resistance than fasting glucose alone.

Synergistic Risk: When high triglycerides and high ALT coexist, the risk of cardiovascular events increases exponentially rather than linearly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Does being obese automatically mean I'll develop MASLD?

A: No. While obesity increases risk, the competing pathways research shows that individual variation means some people develop MASLD while others don't. However, liver screening remains important for all individuals with obesity.

Q: What's the difference between metabolically healthy obesity and other obesity?

A: Recent research suggests the distinction is less meaningful than previously thought. Most "metabolically healthy obese" individuals eventually show metabolic dysfunction markers, particularly liver disease, suggesting monitoring is essential for everyone.

Q: Can I reduce my MASLD and dyslipidemia risk without losing weight?

A: While weight loss is often most effective, research suggests addressing obesity phenotype (where fat is stored), managing inflammation, and treating metabolic dysfunction are all important. Comprehensive treatment may include lifestyle modifications, dietary changes, exercise, and medical interventions.

Q: How often should I be screened for MASLD if I'm obese?

A: Current recommendations suggest periodic liver ultrasound and blood tests. The exact frequency depends on your risk factors, including presence of metabolic dysfunction, dyslipidemia, and other metabolic markers. Discuss screening schedules with your healthcare provider.

Q: Is inflammation always bad for people with obesity?

A: Interestingly, no. Research shows some inflammatory responses protect against infection and support tissue repair. The goal is promoting beneficial inflammation while controlling harmful inflammatory pathways—a more nuanced approach than complete anti-inflammation.

Key Takeaways

✓ Obesity involves competing biological pathways—not everyone develops the same complications despite similar weight

✓ Obesity is a strong predictor of atherogenic dyslipidemia in MASLD patients, creating compounded cardiovascular risk

✓ Metabolically healthy obesity may not be truly "healthy"—many progress to metabolic dysfunction and liver disease

✓ Obesity phenotype matters—where you store fat is as important as how much you weigh

✓ Inflammation in obesity is complex—some responses are protective while others drive disease progression

✓ Personalized approaches are needed—one-size-fits-all obesity treatment is outdated

Author’s Note

This article is intended for educational purposes and synthesizes the most recent research (2025–2026) on obesity, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), cardiometabolic risk, and immunometabolic pathways. The content reflects peer-reviewed scientific literature and aims to provide both clinicians and informed readers with evidence-based insights into the complex interactions between obesity, liver health, and systemic metabolic risk.

While the article offers guidance on risk assessment, body composition, and metabolic monitoring, it is not a substitute for personalized medical advice. Readers are encouraged to consult a qualified healthcare professional for individual evaluation, screening, or treatment.

The author declares no conflicts of interest and receives no funding from commercial sources related to this article.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Managing Diabesity: A Complete Guide to Weight Loss and Blood Sugar Control | DR T S DIDWAL

Stop the Clock: Proven Ways to Reverse Early Aging if You Have Diabetes | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

5 Steps to Reverse Metabolic Syndrome: Diet, Habit, & Lifestyle Plan | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Choe, H. J., Almas, T., Neeland, I. J., Lim, S., & Després, J.-P. (2025). Obesity phenotypes and atherogenic dyslipidemias. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 51, e70151. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.70151

Fotros, D., Hekmatdoost, A., & Yari, Z. (2026). Obesity as a predictor of atherogenic dyslipidemia in patients with metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. Scientific Reports, 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-35525-2

Hirooka, M., Miyake, T., Yano, R., Nakamura, Y., Okazaki, Y., Shimamoto, T., Yukimoto, A., Yamamoto, Y., Watanabe, T., Yoshida, O., Hirooka, K., & Tokumoto, Y. (2026). Competing cardiometabolic pathways of obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Gastro Hep Advances. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastha.2026.100882

Koliaki, C., Dalamaga, M., Kakounis, K., et al. (2025). Metabolically healthy obesity and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Navigating the controversies in disease development and progression. Current Obesity Reports, 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-025-00637-9

Lee, Y. S. (2026). Immunometabolism in obesity: Understanding the beneficial and detrimental roles of inflammation. PLoS Biology, 24(1), e3003620. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003620