MASLD Treatment in 2025: Why Muscle Health, Not Just Weight Loss, Determines Outcomes

Discover MASLD treatment in 2025 and why muscle health matters more than weight loss. Learn evidence-based strategies to reverse fatty liver disease.

METABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/9/202611 min read

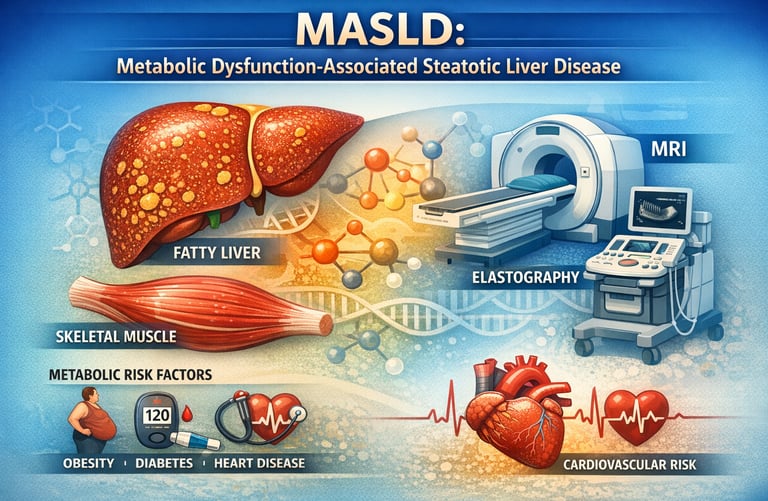

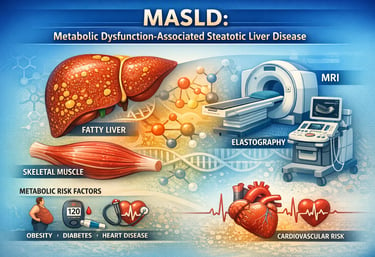

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is rapidly emerging as a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, affecting millions of adults across all populations (Tilg et al., 2026). Formerly referred to as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), MASLD emphasizes the underlying metabolic dysfunction driving liver injury, rather than simple fat accumulation (EASL-EASD-EASO, 2024). As obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes continue to rise globally, understanding MASLD has become essential not only for hepatologists but also for primary care providers, endocrinologists, and individuals concerned with metabolic health (Stefan et al., 2025).

Recent research highlights that MASLD is a multisystem disorder: skeletal muscle quality, mitochondrial function, chronic low-grade inflammation, and gut-liver interactions all play key roles in disease progression (Isakov, 2025). Notably, muscle mass and function strongly influence insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism, often outweighing the impact of weight alone on liver outcomes (Isakov, 2025). Moreover, disease progression is highly heterogeneous—some individuals with substantial hepatic steatosis remain stable, while others rapidly develop fibrosis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma (Tilg et al., 2026).

Advances in non-invasive imaging, biomarker panels, and personalized risk stratification now allow clinicians to detect MASLD earlier and tailor interventions more effectively (Osta et al., 2025). Importantly, treatment is evolving beyond weight loss alone: resistance training, dietary optimisation, and emerging metabolism-targeted pharmacotherapy, such as GLP-1 agonists, are redefining MASLD management (Stefan et al., 2025).

Understanding MASLD today requires a holistic metabolic perspective, integrating liver health, muscle function, cardiovascular risk, and lifestyle interventions to prevent progression and improve long-term outcomes (EASL-EASD-EASO, 2024; Tilg et al., 2026).

Clinical pearls

1. The "Metabolic Bypass" Effect

Scientific: Resistance training (RT) improves hepatic steatosis and insulin sensitivity through non-canonical pathways, independent of significant total body mass reduction. RT upregulates glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) in skeletal muscle, creating a "glucose sink" that alleviates the metabolic burden on the liver.

Patient-Friendly: The scale isn't the boss. You can significantly "de-fat" your liver and improve your health markers even if your body weight stays exactly the same. Building muscle creates a sponge that soaks up extra blood sugar before it can be turned into liver fat.

2. The Synergy of Modalities

Scientific: While RT specifically targets intrahepatic lipid content and ALT/AST normalization, aerobic exercise (AE) remains the gold standard for improving cardiorespiratory fitness, VO 2 max and reducing systemic inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α. A concurrent training model (RT + AE) yields the most robust reduction in the Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI).

Think of resistance training as the "liver fixer" and aerobic exercise (like walking or cycling) as the "heart and lung protector." Doing both gives you a total body shield against the complications of MASLD.

3. Bile Acid Reshaping

Scientific: Recent evidence (Shi et al., 2025) suggests that exercise modulates the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling pathway by altering the circulating bile acid profile. This reduces lipogenesis (fat creation) and promotes fatty acid oxidation within the hepatocytes.

Exercise is a chemical messenger. When you move, your body changes the "chemistry soup" (bile acids) it uses for digestion. This new mixture sends a signal to your liver to stop storing fat and start burning it for fuel.

4. The 8-to-12 Week "Threshold"

Scientific: Meta-analyses indicate that while cellular adaptations in mitochondrial efficiency occur within days, statistically significant architectural changes in hepatic tissue and stabilization of liver enzymes typically require a minimum dose-response period of 8–12 weeks of consistent intervention.

Consistency beats intensity. You don’t need to be an athlete on Day 1, but you do need to stay the course. Your liver cells need about three months of "re-training" before the results show up clearly on your blood tests and scans.

5. Myokine-Mediated Protection

Scientific: Contracting skeletal muscle acts as an endocrine organ, secreting "myokines" (such as Irisin and IL-6) that facilitate cross-talk with the liver. These myokines have been shown to inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells, which are the primary drivers of liver fibrosis (scarring).

Every time you lift weights or push your muscles, they release "healing signals" that travel through your blood to your liver. These signals tell the liver to stop forming scar tissue and keep its texture soft and healthy.

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Everything You Need to Know in 2025

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), represents a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize liver disease. The new terminology reflects a paradigm shift: this isn't simply about excess fat in the liver; it's about underlying metabolic dysfunction that drives both liver disease and systemic health problems.

At its core, MASLD involves abnormal fat accumulation in liver cells (hepatic steatosis), often accompanied by inflammation and potential progression to liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. However, recent research emphasizes that the severity of fat accumulation doesn't always correlate with disease progression—a finding that has important clinical implications.

Study 1: Isakov (2025) – The Muscle-Liver Connection

Isakov (2025) takes a refreshing perspective on MASLD, focusing on an often-overlooked factor: skeletal muscle dysfunction and body mass composition.

Key Findings and Takeaways

Muscle quality matters more than weight alone: The research emphasizes that lean muscle mass and muscle function are critical determinants of metabolic health and liver disease progression

Sarcopenia (muscle loss) is strongly associated with worse MASLD outcomes, independent of obesity status

Metabolic dysfunction isn't purely about adipose tissue—skeletal muscle plays a central role in glucose metabolism, lipid handling, and systemic inflammation

The relationship between body composition and liver disease suggests that treatment strategies should focus not just on weight loss, but on muscle preservation and strength gain

This study challenges the common assumption that simply losing weight is the solution. Instead, it highlights that exercise, particularly resistance training and strength training, may be equally—if not more—important than caloric restriction in managing MASLD.

Study 2: EASL-EASD-EASO (2024) – Clinical Practice Guidelines

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), and European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) released comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for MASLD management in 2024, representing the gold standard for evidence-based care in Europe.

Key Findings and Takeaways

Comprehensive risk stratification is essential—not all patients with hepatic steatosis require the same treatment approach

Lifestyle modifications (diet, exercise, weight loss) remain the cornerstone of treatment, but intensity and individual tailoring are crucial

Pharmacological interventions should be considered in patients with advanced fibrosis or those at high risk for disease progression

Regular screening for hepatic fibrosis and complications is recommended, particularly in patients with metabolic risk factors

Multidisciplinary management involving hepatologists, endocrinologists, and other specialists yields better outcomes

The guidelines emphasize a stepped approach: starting with lifestyle interventions, escalating to pharmacotherapy for specific phenotypes, and monitoring for complications like cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and portal hypertension.

Study 3: Osta et al. (2025) – Diagnostic Insights from a Radiologist's Perspective

Published in Radiographics, this work provides valuable insights into how imaging professionals can identify and characterize MASLD, emphasizing the role of radiology in modern diagnosis and disease management.

Key Findings and Takeaways

Advanced imaging techniques (MRI, elastography) can now assess both hepatic steatosis and fibrosis with greater accuracy than traditional ultrasound

Radiomics and texture analysis show promise in predicting disease severity and treatment response

The updated nomenclature of MASLD (moving away from NAFLD) has important clinical implications for diagnosis codes and patient communication

Non-invasive biomarkers and imaging-based scores can help risk stratify patients without liver biopsy

Early detection through imaging allows for preventive interventions before irreversible damage occurs

Modern radiology enables personalized risk assessment, allowing clinicians to identify patients at highest risk for fibrosis progression and tailor treatment intensity accordingly.

Study 4: Tilg et al. (2026) – Comprehensive Review of MASLD in Adults

This recent publication in JAMA provides a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge about MASLD in adults, covering epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management.

Key Findings and Takeaways

MASLD prevalence continues to rise alongside global increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes

The disease shows remarkable heterogeneity—some individuals with significant steatosis never progress, while others develop cirrhosis rapidly

Genetic factors, environmental factors, and individual metabolic phenotypes all influence disease trajectory

Screening asymptomatic individuals with metabolic risk factors can identify disease at earlier, more treatable stages

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in MASLD patients, highlighting the systemic nature of this condition

Understanding that MASLD is not just a liver disease but a marker of systemic metabolic dysfunction shifts clinical focus toward comprehensive metabolic health management rather than isolated liver-focused interventions.

Study 5: Stefan et al. (2025) – Pathomechanisms and Metabolism-Based Treatment

In The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Stefan and colleagues explore the diverse pathophysiological mechanisms underlying MASLD and how understanding these mechanisms can guide metabolism-based treatments.

Key Findings and Takeaways

MASLD results from multiple interacting pathways: hepatic lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and metabolic inflammation

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists show promise in improving insulin sensitivity, promoting weight loss, and potentially reversing liver fibrosis

Metabolic heterogeneity means that individuals may have different drivers of disease, requiring personalized treatment approaches

Metabolic endotoxemia (increased bacterial lipopolysaccharides) plays a role in perpetuating systemic inflammation and liver damage

Mitochondrial function and metabolic flexibility are key treatment targets

This research suggests we're entering an era of metabolism-targeted therapy where treatment is guided by an individual's specific metabolic phenotype rather than generic protocols.

The Comprehensive Picture: Integrating Current Evidence

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease results from a perfect storm of factors:

Metabolic factors include insulin resistance, impaired glucose metabolism, and abnormal lipid metabolism. Obesity and visceral adiposity (fat around internal organs) are strong risk factors, but lean individuals can develop MASLD due to metabolic dysfunction alone.

Inflammatory pathways including chronic low-grade inflammation, altered microbiome composition, and increased intestinal permeability all contribute to liver injury.

Genetic predisposition determines who develops MASLD among those with metabolic risk factors. Certain genetic variants (like PNPLA3 and TM6SF2) significantly increase susceptibility.

Lifestyle factors such as high-fructose diet, sedentary behavior, sleep deprivation, and chronic stress all promote disease development.

The Natural History: How MASLD Progresses

Not all MASLD progresses. In fact, many individuals with hepatic steatosis remain stable or even improve their liver health with lifestyle modifications. However, approximately 20-30% progress to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with significant fibrosis (MASLD-F) or eventually cirrhosis.

Factors predicting progression include:

Presence of liver fibrosis at diagnosis

Advanced age

Type 2 diabetes

Obesity and metabolic complications

Elevated liver enzymes and inflammatory markers

Diagnosis: From Suspicion to Confirmation

Clinical Assessment

The diagnostic journey begins with risk stratification. Patients with metabolic risk factors—obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or hypertension—warrant evaluation for MASLD.

Imaging and Biomarkers

Ultrasound can detect hepatic steatosis but cannot assess fibrosis. CT and MRI provide more precise quantification. Elastography (both transient and shear wave elastography) non-invasively measures liver stiffness, a surrogate for fibrosis.

Biomarker panels combining clinical data, blood tests (like FIB-4 score, NAFLD Fibrosis Score), and imaging provide risk stratification without liver biopsy in most cases.

Liver Biopsy

Though historically the gold standard, biopsy is now reserved for cases where non-invasive testing is inconclusive or when research protocols require it.

Treatment Strategies: The Multi-Modal Approach

Lifestyle Modifications: The Foundation

Weight loss of 5-10% improves hepatic steatosis; 15% or more improves liver inflammation and fibrosis. However, as Isakov's research emphasizes, the quality of weight loss matters—preserving lean muscle mass while reducing adipose tissue is ideal.

Dietary approaches include the Mediterranean diet, DASH diet, and restriction of fructose and ultra-processed foods. Research increasingly supports intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating for metabolic improvement.

Physical activity should include both aerobic exercise and resistance training. Resistance training is particularly important given the muscle-centric findings from recent research.

Pharmacological Approaches

Based on current evidence, several medications show promise:

GLP-1 Agonists (semaglutide, tirzepatide) improve insulin sensitivity, promote weight loss, and show potential in reducing liver fibrosis. These are increasingly considered first-line pharmacotherapy.

SGLT-2 Inhibitors improve metabolic parameters and may reduce liver disease progression.

FXR Agonists and other nuclear receptor ligands are in development, showing promise in clinical trials.

Antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents are being studied, though evidence remains mixed.

FAQs: Answering Your MASLD Questions

Q1: If I have a fatty liver, do I definitely have MASLD?

A: Not necessarily. You have hepatic steatosis (fat in the liver), but MASLD specifically refers to steatosis in the context of metabolic dysfunction. If you have metabolic risk factors (obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes) alongside steatosis, you likely have MASLD. However, some individuals with steatosis have completely normal metabolic parameters—a condition called metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease without metabolic dysfunction, or individuals without metabolic abnormalities may have alcohol-related liver disease instead.

Q2: Can MASLD be reversed?

A: Yes, in many cases. Hepatic steatosis can improve or resolve completely with weight loss, improved diet, and increased exercise, particularly if caught early before significant fibrosis develops. However, advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis are generally irreversible, though progression can be halted.

Q3: Do I need medication if I have MASLD?

A: Not everyone. Lifestyle modifications should always be the first step. However, if you have advanced fibrosis, type 2 diabetes, or obesity alongside MASLD, your doctor may recommend pharmacotherapy alongside lifestyle changes.

Q4: How often should I be screened for MASLD complications?

A: This depends on your fibrosis stage. Those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis need regular screening for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and portal hypertension complications. Your hepatologist will recommend an individualized screening schedule.

Q5: Is MASLD the same as NAFLD?

A: The terminology has evolved. NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) is now called MASLD because the newer term better reflects the underlying pathophysiology—metabolic dysfunction, not merely the absence of alcohol. All the core concepts remain the same, but the rebranding emphasizes the metabolic nature of the disease.

Q6: Can lean individuals develop MASLD?

A: Yes. While obesity is a major risk factor, approximately 20-30% of MASLD occurs in lean or normal-weight individuals, particularly those with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes. Genetic factors and metabolic dysfunction can drive disease independent of body weight.

Q7: How does muscle loss contribute to MASLD?

A: Skeletal muscle is a major site of glucose uptake and lipid metabolism. Muscle loss impairs insulin sensitivity, promotes metabolic inflammation, and reduces overall metabolic flexibility. This is why maintaining muscle mass through resistance training is increasingly emphasized in MASLD management.

Author’s Note

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) represents one of the fastest-growing chronic liver conditions worldwide, yet it remains widely misunderstood and often underestimated in clinical practice. For many years, management strategies focused almost exclusively on weight loss and pharmacologic approaches, despite inconsistent long-term success. The recent shift in terminology from NAFLD to MASLD reflects a deeper scientific understanding: this is fundamentally a metabolic disease, not merely a hepatic one.

The purpose of this article is to translate the most current 2025–2026 scientific evidence into clear, practical insights for clinicians, researchers, and health-conscious readers. The studies cited here—including systematic reviews and meta-analyses—demonstrate that structured exercise, particularly resistance training, directly targets the biological mechanisms driving hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, inflammation, and fibrosis progression. Importantly, these benefits occur even in the absence of substantial weight loss, challenging long-held assumptions about treatment priorities.

As a physician, I wrote this piece to emphasize that exercise is not an optional lifestyle recommendation, but a foundational therapeutic intervention in MASLD management. When combined with reasonable, sustainable dietary modifications, physical activity offers a powerful, low-cost strategy capable of halting—and in many cases reversing—early disease progression.

This article is intended for educational purposes and does not replace individualized medical care. Patients with advanced liver disease should always consult their healthcare provider before initiating new exercise programs. My hope is that this evidence-based synthesis empowers readers to view movement not simply as fitness, but as medicine—one of the most effective tools we currently have to restore metabolic and liver health.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting a resistance exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

Metabolic Plasticity: Epigenetic Adaptations to Calorie Restriction | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

References

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), & European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). (2024). EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Journal of Hepatology, 81(3), 492–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.04.031

Isakov, V. (2025). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A story of muscle and mass. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 31(20), 105346. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i20.105346

Osta, E., Saenz Rios, F., Jaganathan, S., Thomas, C., Tsai, E., Surabhi, V. R., Prasad, S. R., & Katabathina, V. S. (2025). Current update on nomenclature, diagnosis, and management of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease: Radiologists' perspective. Radiographics, 45(12), e240221. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.240221

Stefan, N., Yki-Järvinen, H., & Neuschwander-Tetri, B. A. (2025). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Heterogeneous pathomechanisms and effectiveness of metabolism-based treatment. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 13(2), 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00318-8

Tilg, H., Petta, S., Stefan, N., & Targher, G. (2026). Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults: A review. JAMA, 335(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.19615