How Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Influence Type 2 Diabetes

Understand the science behind the Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load. Explore how different carbs impact blood sugar and how to build a low GI diet.

DIABETES

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

1/19/202617 min read

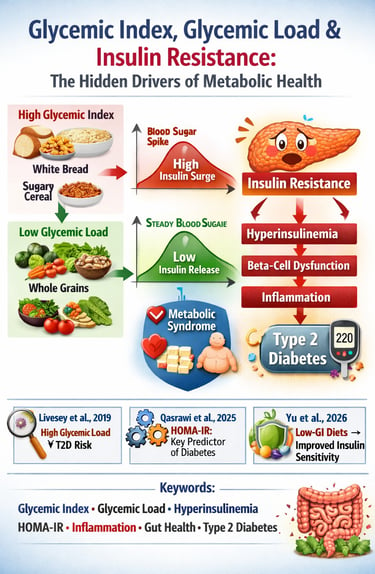

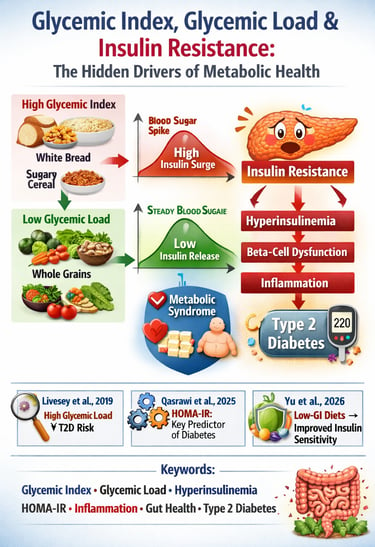

If you’ve ever eaten a bowl of white rice and felt a rush of energy followed by an afternoon crash, you’ve experienced the metabolic power of the glycemic index, glycemic load, and their influence on insulin resistance. These concepts are not trendy nutrition buzzwords—they are measurable physiological mechanisms that determine how efficiently your body processes glucose, how hard your pancreas must work to produce insulin, and whether you drift toward hyperinsulinemia, metabolic syndrome, or Type 2 Diabetes. High-GI and high-GL foods—especially refined carbohydrates—trigger rapid spikes in postprandial glucose, forcing the pancreas to release large amounts of insulin. Over time, this chronic metabolic stress leads to “insulin exhaustion,” cellular insulin desensitization, and eventually beta-cell dysfunction (Willett et al., 2002).

Key research shows that glycemic load—not just the glycemic index—is the strongest dietary predictor of Type 2 Diabetes incidence (Livesey et al., 2019). Even more compelling, modern machine-learning analyses reveal that insulin-based measures such as fasting insulin and HOMA-IR predict diabetes far more accurately than glucose alone, proving insulin resistance precedes glucose elevation by years (Qasrawi et al., 2025). Low-GI and low-GL diets improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, stabilize postprandial responses, and support healthier gut microbiome composition—independent of weight loss (Yu et al., 2025).

Clinical Pearls :

1. Glycemic Load (GL) is the Superior Metric for Clinical Risk Assessment

While the GI measures the quality of a carbohydrate in isolation, the Glycemic Load (GL)—which accounts for both quality and quantity (serving size)—provides the stronger, more complete predictor of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) risk in prospective studies.

Pearl: Focus patient education on the total GL of the meal, not just the GI of individual foods. A high-GI food (like watermelon) can have a low GL and minimal metabolic impact due to low carbohydrate density, whereas a large portion of a medium-GI food (like brown rice) can result in a dangerously high GL.

Supporting Evidence: The Livesey et al. (2019) meta-analysis showed a robust, statistically significant association between high dietary GL and T2D incidence, confirming it as a genuine, independent risk factor.

2. Insulin Resistance Precedes Glucose Elevation and Is the Key Intervention Window

The primary metabolic dysfunction that predicts T2D is the inability of cells to respond to insulin, often manifesting as compensatory hyperinsulinemia (high insulin levels) long before blood glucose levels enter the diabetic range.

Pearl: The goal of low-GI/low-GL diets is primarily to reduce chronic insulin demand (hyperinsulinemia), not just to flatten glucose spikes. Preventing excessive insulin secretion in the pre-diabetic phase is the most critical intervention strategy.

Supporting Evidence: The Qasrawi et al. (2025) machine learning study demonstrated that insulin-based measures of resistance (like HOMA-IR) are the most predictive variables for future diabetes incidence, underscoring that the insulin dysfunction precedes the glucose dysfunction.

3. Fiber and Macronutrient Pairing are the Most Potent GI-Lowering Strategies

The mechanical and chemical properties of a meal, especially the presence of fiber, protein, and fat, dramatically dictate the rate of glucose absorption, overriding the isolated GI value of the carbohydrate component.

Pearl: Counsel patients to never eat a high-GI carbohydrate alone. Always recommend pairing it with soluble fiber (e.g., legumes, oats) and protein/healthy fat (e.g., nuts, avocado). These additions slow gastric emptying and glucose absorption, effectively reducing the overall meal GL and postprandial insulin spike.

Mechanism Insight: Fiber creates a viscous barrier in the small intestine, slowing the rate at which digestive enzymes access the starch, thus lowering the effective GI.

4. Low-GI Diets Improve Insulin Sensitivity Independent of Weight Loss

The physiological benefits of low-GI/low-GL eating are not simply due to associated calorie restriction or weight loss; they involve a direct improvement in cellular insulin signaling and function.

Pearl: Low-GL interventions should be recommended even for patients who are not overweight but who show metabolic dysfunction (e.g., elevated fasting insulin, genetic risk). These diets provide measurable, objective improvements in markers like HOMA-IR through reduced postprandial glucose excursions.

Supporting Evidence: The Yu et al. (2025) meta-analysis confirmed that low-GI dietary interventions produced measurable improvements in insulin sensitivity markers in non-diabetic adults, even without substantial weight loss.

5. High Glycemic Load Contributes to Systemic Inflammation via the Gut

The adverse metabolic effects of high GL extend beyond the immediate glucose-insulin axis, driving insulin resistance through an inflammatory cascade originating in the gut.

Pearl: High GL, fiber-poor diets promote intestinal dysbiosis (unhealthy gut bacteria) and leaky gut, allowing bacterial products (like LPS) to enter circulation and trigger low-grade chronic inflammation. This inflammation directly interferes with insulin signaling at the molecular level.

Mechanism Insight: Inflammation causes serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1), which effectively blocks the critical tyrosine phosphorylation required for the insulin signal to pass into the cell. Low-GI/high-fiber diets strengthen the gut barrier and reduce this systemic inflammatory insult.

Glycemic Index and Load: Key Dietary Factors in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance

What Are Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load? Demystifying the Science

Before diving into the research, let's establish what we're actually talking about—because precision matters when discussing metabolic health.

Glycemic Index: The Quality Question

The glycemic index (GI) measures how quickly a food raises your blood glucose compared to pure glucose or white bread (which serve as reference standards at 100 on the scale). This metric examines the quality of carbohydrates in isolation.

Foods are categorized as:

Low GI (≤55): Whole grains, legumes, non-starchy vegetables, certain fruits

Medium GI (56-69): Whole wheat, brown rice, oatmeal

High GI (≥70): White bread, refined cereals, sugary drinks, processed snacks

A whole grain oat has a GI of approximately 55, meaning it causes a gradual, moderate blood glucose rise. White bread, by contrast, has a GI around 75, triggering a rapid glucose spike.

Glycemic Load: The Quantity Question

Glycemic load (GL) accounts for both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates in a realistic serving size. It's calculated as: (GI × carbohydrate grams per serving) ÷ 100.

This distinction matters profoundly. Watermelon, for instance, has a high GI (around 80) but low GL (about 5) because a typical serving contains relatively few carbohydrates. The glycemic load provides a more complete picture of how a food actually impacts your blood sugar in the context of a real meal.

The Research Foundation: Six Landmark Studies on Glycemic Index, Load, and Insulin Resistance

Study 1: Willett, Manson, and Liu (2002) — The Foundational Evidence

This seminal paper from Harvard's preeminent nutrition researchers served as the cornerstone for understanding how dietary carbohydrate quality influences type 2 diabetes risk. By synthesizing evidence from prospective cohort studies, Willett and colleagues demonstrated that both high glycemic index foods and overall high glycemic load patterns substantially elevated diabetes incidence.

Key Findings:

The research revealed a striking dose-response relationship: individuals consuming diets with the highest glycemic load demonstrated approximately 1.4 times greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to those consuming the lowest GL. The glycemic index of the overall diet also emerged as an independent risk factor, even after accounting for total carbohydrate intake—a finding that definitively separated the importance of carbohydrate quality from mere quantity.

The authors proposed that high glycemic index foods cause exaggerated postprandial (after-eating) glucose spikes, forcing the pancreas to secrete excessive insulin repeatedly throughout the day. Over months and years, this constant demand exhausts pancreatic beta cells and leads to cellular insulin resistance through a phenomenon called "glucose toxicity"—where chronically elevated blood glucose itself impairs insulin signaling pathways.

Key Takeaway: The quality of carbohydrates matters as much as—or more than—the quantity for insulin resistance prevention.

Study 2: Yu et al. (2025) — Contemporary Meta-Analysis Evidence

This recent systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized multiple randomized controlled trials to determine whether reducing glycemic index could improve insulin resistance in non-diabetic adults—the critical prevention window. With the advantage of recent evidence, Yu and colleagues provided updated quantitative estimates of intervention effectiveness.

Key Findings:

The meta-analysis confirmed that dietary interventions specifically targeting lower glycemic index foods produced measurable improvements in insulin sensitivity markers, particularly the HOMA-IR index (Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance). Adults who adopted low glycemic index dietary patterns showed average improvements in fasting insulin levels and calculated insulin resistance indices, even without substantial weight loss.

Notably, improvements appeared more pronounced in individuals who were already showing early signs of metabolic dysfunction, suggesting that low glycemic index diets work as both prevention and early intervention tools.

The analysis highlighted that low glycemic index foods reduce postprandial hyperglycemia (excessively high blood sugar after meals), which decreases the overall insulin demand across the day. With lower insulinemic burden, pancreatic cells experience less stress, and peripheral tissues have more opportunity to restore normal glucose transporter expression and insulin signaling at the cellular level.

Key Takeaway: Reducing dietary glycemic index produces measurable, physiologically meaningful improvements in insulin resistance markers within relatively short intervention periods.

Study 3: Livesey et al. (2019) — The Comprehensive Prospective Analysis

This extensive systematic review and meta-analysis examined prospective cohort studies following populations over years to determine whether high glycemic load diets genuinely predict type 2 diabetes development. With inclusion of 37 prospective studies involving hundreds of thousands of participants, this represents one of the most comprehensive analyses available.

Key Findings:

The combined evidence demonstrated a robust, statistically significant association between high dietary glycemic load and type 2 diabetes incidence (Livesey et al., 2019). Participants in the highest quintile (top 20%) of glycemic load consumption showed approximately 1.27 times greater risk of developing diabetes compared to the lowest quintile. The glycemic index as an independent metric showed a weaker but still significant association.

Intriguingly, the relationship appeared stronger in women and in specific populations—suggesting that factors like hormonal status, physical activity levels, and baseline metabolic health influence how much glycemic index and glycemic load matter.

The authors discussed multiple mechanisms whereby high glycemic load promotes insulin resistance: repeated high glucose spikes impair glucose transporter function, chronic high insulin levels trigger negative feedback loops that reduce insulin receptor sensitivity, and hyperglycemia itself generates oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines that interfere with insulin signaling at the molecular level. Additionally, high glycemic load patterns often displace nutrient-dense, fiber-rich whole foods, compounding metabolic dysfunction.

Key Takeaway: Decades of prospective data confirm that dietary glycemic load is a genuine, independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes, with stronger effects in some populations than others.

Study 4: Vlachos et al. (2020) — Clinical Management Perspective

Study Overview:

Shifting from prevention to management, this clinical review examined how low glycemic index and low glycemic load dietary interventions could improve postprandial glucose control in patients already diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. This research is crucial because insulin resistance in diabetics becomes self-perpetuating—chronically high blood glucose worsens insulin sensitivity further.

Dietary interventions emphasizing low glycemic index and moderate glycemic load consistently reduced postprandial glucose peaks in diabetic patients, with improvements sometimes rivaling or complementing pharmacological interventions (Vlachos et al., 2020). The benefits extended beyond glucose control: improved postprandial hyperglycemia correlated with better HbA1c levels (markers of average blood sugar over three months), improved lipid profiles, and reduced inflammation markers.

Critically, the review found that low glycemic load patterns appeared more effective than low glycemic index alone when both dietary quality and quantity mattered—particularly in individuals already exhibiting significant insulin resistance.

In established diabetes, insulin resistance becomes multifactorial, involving beta cell dysfunction, hepatic glucose overproduction, and severe peripheral tissue insulin insensitivity. Low glycemic index foods reduce the glucose excursions that would otherwise trigger compensatory hyperinsulinemia, while moderate glycemic load prevents both hypoglycemic episodes and excessive hyperglycemia, creating a more stable metabolic environment where remaining insulin sensitivity can function optimally.

Key Takeaway: Glycemic index and glycemic load management becomes a cornerstone of type 2 diabetes management, influencing both immediate glucose control and long-term metabolic outcomes.

Study 5: Qasrawi et al. (2025) — Predictive Biomarker Approach

Representing the cutting edge of precision nutrition science, this study employed machine learning algorithms to identify which specific glycemic control metrics—encompassing fasting glucose, insulin levels, HbA1c, and indirect measures of insulin resistance—most powerfully predicted who would develop type 2 diabetes. This approach reveals the relative importance of different metabolic markers.

Key Findings:

The machine learning models identified that insulin-based measures of resistance (particularly fasting insulin and calculated HOMA-IR) emerged as among the most predictive variables for diabetes incidence, even more so than baseline glucose levels alone (Qasrawi et al., 2025). This finding underscores that insulin resistance itself—the fundamental physiological dysfunction—precedes and predicts glucose elevation.

The research demonstrated that dietary patterns creating lower postprandial insulin demand (achieved through low glycemic index and moderate glycemic load choices) could theoretically be incorporated into predictive algorithms to identify individuals most likely to benefit from dietary intervention.

The study highlighted that insulin resistance exists on a spectrum long before diabetic-range blood glucose emerges. Individuals with elevated fasting insulin but normal fasting glucose already demonstrate compensatory hyperinsulinemia—the pancreas is working overtime to maintain glucose control. This phase represents the critical intervention window where dietary glycemic index optimization could prevent disease progression.

Key Takeaway: Insulin resistance markers predict diabetes risk better than glucose alone, emphasizing that preventing excessive insulin demand through low glycemic index nutrition represents early prevention at the metabolic foundation.

Study 6: Vitale et al. (2025) — Population-Level Real-World Evidence

This recent epidemiological study by Vitale et al. (2025) extended beyond controlled research settings to real-world community-dwelling older adults, utilising 24-hour dietary recall data to investigate whether glycemic load consumption was associated with glycemic control and diabetes prevalence. This research bridges the gap between clinical evidence and actual population health patterns.

Key Findings:

The study confirmed that community-dwelling older adults consuming higher glycemic load diets exhibited worse fasting glucose levels and greater diabetes prevalence, even after accounting for age, body mass index, and physical activity. Notably, the association remained significant in this real-world population despite the dietary assessment limitations of 24-hour recall methodology.

The findings suggest that the relationship between dietary glycemic load and metabolic health extends beyond research subjects to genuine population patterns—people eating more high glycemic index foods systematically develop worse glycemic control and more diabetes.

In older adults, insulin resistance naturally increases with age due to declining muscle mass, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation. This makes dietary management of glycemic load even more critical; older individuals have less metabolic "margin for error" and cannot tolerate consistently high glycemic load consumption without metabolic consequences.

Key Takeaway: Real-world epidemiological data confirms that dietary glycemic load patterns meaningfully influence population-level glycemic control and diabetes prevalence across age groups.

The Mechanisms: How Glycemic Index and Load Drive Insulin Resistance

Understanding why high glycemic index and high glycemic load foods promote insulin resistance requires examining the molecular cascades triggered in your body.

The Postprandial Hyperglycemia Hypothesis

When you consume high glycemic index foods, blood glucose rises rapidly and dramatically. Your pancreatic beta cells detect this rise and secrete insulin in proportion to the glucose elevation. This works fine acutely, but consider what happens when you consume high glycemic index foods three times daily for months and years:

Your body experiences chronic, repeated hyperglycemic spikes. The pancreas constantly secretes insulin at elevated levels—a condition called hyperinsulinemia. Over time, peripheral tissues (muscle, fat, liver) become desensitized to chronic high insulin levels through a process called downregulation: the cells reduce the number of insulin receptors on their surface or reduce post-receptor signaling efficiency.

This is insulin resistance in action: your cells have learned to ignore insulin because it's constantly present at high levels. Paradoxically, your body responds by producing even more insulin—creating a vicious cycle where hyperinsulinemia worsens insulin resistance, which triggers more hyperinsulinemia.

Glucose Toxicity and Oxidative Stress

Chronically elevated glucose levels—even those not yet diabetic-range—trigger oxidative stress within cells. Hyperglycemia accelerates glycation (non-enzymatic binding of glucose to proteins), generating advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that damage cellular machinery and trigger inflammatory responses.

These AGEs bind to RAGE receptors (Receptor for AGEs), activating NF-kappaB signaling—a master inflammatory pathway. Increased nuclear factor-kappa B activity causes cells to produce inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-6) that directly interfere with insulin signaling pathways by causing serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), preventing normal tyrosine phosphorylation necessary for signal propagation.

Low glycemic index foods prevent this oxidative cascade by maintaining more stable, moderate glucose levels that don't trigger excessive AGE formation or RAGE activation.

Lipid Accumulation and Lipotoxicity

High glycemic load diets often pair with excessive refined carbohydrate consumption, which the liver converts to lipogenesis (fat synthesis). This leads to increased hepatic and visceral fat accumulation, which generates free fatty acids that impair insulin signaling through protein kinase C (PKC) and JNK pathway activation.

Conversely, low glycemic load patterns typically emphasize whole foods higher in fiber and micronutrients, with lower overall caloric density, reducing lipogenic stimulus and lipotoxic metabolic damage.

Intestinal Dysbiosis and Endotoxemia

Emerging research shows that high glycemic load diets rich in refined carbohydrates and low in fiber alter gut microbiota composition, promoting dysbiosis—an unhealthy microbial ecosystem. This dysbiosis increases intestinal permeability ("leaky gut"), allowing bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to enter the bloodstream.

Circulating LPS activates TLR4 receptors, triggering chronic low-grade endotoxemia and systemic inflammation that impairs insulin signaling across tissues. Low glycemic index foods rich in dietary fiber promote beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which strengthen intestinal barrier function and reduce endotoxemia.

Practical Translation: Applying the Science to Your Plate

The research consensus is clear: low glycemic index and moderate glycemic load eating patterns prevent insulin resistance and improve metabolic health. But how does this translate to real-world nutrition?

Strategic Food Substitutions

Instead of white bread (GI 75, GL 15), choose whole-grain bread (GI 51, GL 8). Rather than sugary breakfast cereal (GI 85, GL 21), select steel-cut oats (GI 42, GL 12). Replace white rice (GI 73, GL 22) with brown rice (GI 65, GL 16) or quinoa (GI 59, GL 18).

Combining Foods to Lower Glycemic Load

A simple sandwich on white bread has a high glycemic load, but add a side of nuts, Greek yogurt, or avocado—foods rich in protein and fat—and you dramatically reduce the overall glycemic response through macronutrient dilution. This explains why the research emphasizes total meal glycemic load, not individual food items.

Prioritizing Whole Foods and Fiber

Nearly all low glycemic index foods share a common feature: dietary fiber. Whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits contain soluble fiber that slows gastric emptying and glucose absorption, naturally lowering glycemic index and glycemic load. Aim for 25-35 grams of fiber daily from whole food sources.

Portion Awareness

Remember, glycemic load accounts for serving size. A massive bowl of brown rice has a higher GL than a small bowl, even though it's the same food. Strategic portion sizing—what some researchers call "** caloric restriction without the hunger**"—reduces glycemic load without requiring complex carbohydrate elimination.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is all high glycemic index food unhealthy?

A: Not necessarily. Some high glycemic index foods like certain fruits offer valuable micronutrients, phytochemicals, and fiber. Context matters: a portion of watermelon (high GI, low GL) is quite different metabolically from white bread (high GI, moderate-to-high GL). Focus on glycemic load and overall diet quality rather than obsessing over individual foods.

Q: Can I eat high glycemic index foods if I exercise regularly?

A: Yes, with nuance. Regular physical activity dramatically improves insulin sensitivity, creating more metabolic "flexibility" to handle higher glycemic load foods. Athletes often benefit from strategically timed high glycemic index foods around workouts. However, sedentary individuals with metabolic risk factors should prioritize low glycemic load choices.

Q: Do artificial sweeteners solve the glycemic index problem?

A: Artificial sweeteners prevent blood glucose spikes, but emerging research shows they may alter gut microbiota, impair glucose tolerance, and paradoxically worsen metabolic outcomes in some individuals. They're likely neutral-to-slightly-negative compared to whole food-based carbohydrates, and certainly inferior to low glycemic index whole foods.

Q: How long before a low glycemic load diet improves insulin resistance?

A: The research suggests measurable improvements appear within weeks to months. The Yu et al. (2025) meta-analysis found improvements in insulin sensitivity markers within relatively short intervention periods. However, reversing years of insulin resistance typically requires sustained dietary change—the research baseline is months to years, not days.

Q: Does glycemic load matter more than overall calorie intake?

A: Both matter, but in different ways. Caloric excess promotes weight gain and insulin resistance, while high glycemic load promotes insulin resistance even at equivalent calories. Ideally, you achieve both caloric balance (through low glycemic load foods that naturally satisfy without excess calories) and optimal glycemic load.

Q: Are there genetic factors that make glycemic index more or less important for me personally?

A: Yes, genetic variation in genes like TCF7L2 and FTO influences insulin secretion and glucose regulation. However, the research shows that glycemic index optimization benefits essentially everyone—genetic factors influence magnitude of effect, not direction. The principle holds universally.

Key Takeaways: What the Evidence Clearly Demonstrates

After examining six landmark studies spanning two decades of research, several conclusions emerge with crystalline clarity:

Dietary glycemic index and glycemic load are independent risk factors for type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. They matter beyond simple caloric content (Willett et al., 2002; Livesey et al., 2019).

Reducing dietary glycemic index and glycemic load produces measurable improvements in insulin sensitivity markers even in non-diabetic populations and without major weight loss (Yu et al., 2025).

Glycemic load management becomes increasingly important in established diabetes and older populations where insulin resistance is more pronounced (Vlachos et al., 2020; Vitale et al., 2025).

Insulin resistance itself—not just elevated glucose—is the primary metabolic dysfunction that predicts diabetes development, and preventing excessive insulin demand represents the fundamental prevention strategy (Qasrawi et al., 2025).

The mechanisms are well-understood, involving postprandial hyperglycemia, glucose toxicity, lipid accumulation, and gut dysbiosis—all preventable through dietary glycemic index optimization (mechanisms discussed above).

Real-world population data confirms that these relationships extend beyond research subjects to actual public health patterns (Vitale et al., 2025).

The Bottom Line: Your Dietary Decisions Shape Your Metabolic Destiny

Insulin resistance develops gradually, silently, through years of metabolic choices. But here's the empowering truth: you can reverse this process through deliberate dietary strategies centered on low glycemic index and moderate glycemic load eating.

This doesn't require obsessive food tracking, elimination diets, or perpetual hunger. Instead, it requires strategic substitution: choosing whole grains instead of refined grains, combining macronutrients thoughtfully, prioritizing fiber-rich whole foods, and becoming aware of how different foods actually affect your post-meal glucose and insulin responses.

The research from Willett's foundational work through Yu's recent meta-analysis paints an unmistakable picture: dietary glycemic index and load are modifiable risk factors for the metabolic disease epidemic reshaping modern health. You have agency here. Your fork is a powerful tool.

Call to Action: Transform Your Metabolic Health Today

Don't let insulin resistance silently develop in the background of your metabolic story. The research is definitive, the mechanisms are clear, and the tools are available.

Start today with three simple changes:

Identify one high glycemic index staple in your current diet (white bread, sugary cereal, white rice) and commit to swapping it for a low glycemic index alternative this week.

Add a fiber-rich whole food to each meal—beans, whole grains, non-starchy vegetables. This simple addition dramatically lowers overall meal glycemic load.

Pair carbohydrates strategically with protein and healthy fat to reduce postprandial glucose spikes. A piece of fruit with a handful of nuts, whole grain toast with avocado—these combinations exploit fundamental metabolic physiology.

Your metabolic health isn't destiny—it's a choice, made fresh at every meal. The research in this article represents decades of evidence pointing toward one conclusion: low glycemic index and moderate glycemic load eating patterns prevent insulin resistance and restore metabolic vitality.

The time to begin is now.

Author’s Note

This article reflects my commitment to presenting evidence-based, clinically relevant, and physiologically accurate explanations of metabolic health. As a physician and researcher, I rely on rigorous scientific literature, including large-scale epidemiological studies, randomized controlled trials, mechanistic analyses, and meta-analyses from leading medical journals. Each concept—whether glycemic index, glycemic load, insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, or metabolic inflammation—is evaluated through the lens of both biochemical pathways and practical clinical outcomes.

The goal is not simply to describe what happens in the body, but to reveal why it happens and how individuals can intervene early. Modern research shows that insulin resistance develops years before blood glucose rises, meaning early dietary modifications may prevent or delay Type 2 Diabetes in millions of individuals. By translating complex physiology into understandable frameworks, I aim to empower readers—clinicians, students, and informed patients—to make informed decisions grounded in science rather than nutritional trends.

While no single dietary strategy fits all individuals, the consistent finding across studies is that managing glycemic load, improving fiber intake, and reducing ultra-processed carbohydrates can dramatically

Related Articles

Feed Your Gut, Fuel Your Health: Diet, Microbiota, and Systemic Health | DR T S DIDWAL

What’s New in the 2025 Blood Pressure Guidelines? A Complete Scientific Breakdown | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

5 Steps to Reverse Metabolic Syndrome: Diet, Habit, & Lifestyle Plan | DR T S DIDWAL

The Role of Cholesterol in Health and Disease: Beyond the "Bad" Label | DR T S DIDWAL

Lowering Cholesterol with Food: 4 Phases of Dietary Dyslipidemia Treatment | DR T S DIDWAL

High Triglyceride Levels: 5 New Facts to Help You Lower Your Risk | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Livesey, G., Taylor, R., Livesey, H. F., Buyken, A. E., Jenkins, D. J. A., Augustin, L. S. A., Sievenpiper, J. L., Barclay, A. W., Liu, S., Wolever, T. M. S., Willett, W. C., Brighenti, F., Salas-Salvadó, J., Björck, I., Rizkalla, S. W., Riccardi, G., Vecchia, C. L., Ceriello, A., Trichopoulou, A., Poli, A., … Brand-Miller, J. C. (2019). Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and updated meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients, 11(6), 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061280

Qasrawi, R., Thwib, S., Issa, G., Ghoush, R. A., & Amro, M. (2025). Type 2 diabetes risk prediction using glycemic control metrics: A machine learning approach. Human Nutrition & Metabolism, 42, 200341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hnm.2025.200341

Vitale, M. C. F., Freiria, C. N., de Brito, T. R. P., et al. (2025). Glycemic load, glycemia, and self-reported diabetes mellitus in community-dwelling older adults: A 24-hour dietary recall–based assessment. Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders, 24, 194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-025-01703-8

Vlachos, D., Malisova, S., Lindberg, F. A., & Karaniki, G. (2020). Glycemic index (GI) or glycemic load (GL) and dietary interventions for optimizing postprandial hyperglycemia in patients with T2 diabetes: A review. Nutrients, 12(6), 1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061561

Willett, W., Manson, J., & Liu, S. (2002). Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(1), 274S–280S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.1.274s

Yu, Y., Fu, Y., Chen, Y., Fang, Y., & Tsai, M. (2025). Effect of dietary glycemic index on insulin resistance in adults without diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 12, 1458353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1458353