Feed Your Gut, Fuel Your Health: Diet, Microbiota, and Systemic Health

Learn how diet shapes the gut microbiota and influences energy, immunity, and brain health through fiber, fermented foods, and the gut–brain axis.

NUTRITION

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

12/29/202511 min read

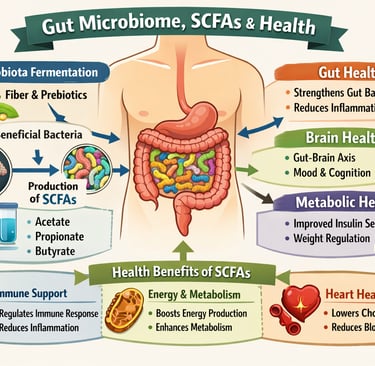

The gut microbiome—the trillions of microorganisms living in our intestines—plays a central role in shaping overall health. One of its most important functions is the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which are generated when beneficial gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber (Mukhopadhya & Louis, 2025).

SCFAs help strengthen the intestinal barrier, preventing harmful substances from entering the bloodstream and reducing chronic inflammation. Butyrate, in particular, serves as the primary energy source for colon cells and supports gut lining repair, helping maintain intestinal integrity (Zhao et al., 2025). Beyond the gut, SCFAs regulate immune function, lowering systemic inflammation and influencing immune cell development (Sanz et al., 2025).

SCFAs also play a critical role in metabolic health, improving insulin sensitivity, regulating appetite hormones, and supporting healthy weight control (Zhao et al., 2025). Importantly, they participate in the gut–brain axis, influencing mood, cognition, and stress responses through neural and biochemical signaling pathways (Sanz et al., 2025).

Low SCFA production has been associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory bowel disorders (Mukhopadhya & Louis, 2025). Diets rich in dietary fiber, plant polyphenols, and fermented foods, combined with regular physical activity, promote microbial diversity and robust SCFA production, translating daily lifestyle choices into measurable benefits for gut, metabolic, immune, and brain health (Reljic et al., 2025).

This comprehensive guide explores the latest research on the gut-health connection, what your beneficial gut bacteria really do, and practical steps you can take today to optimize your gut microbial health.

Clinical pearls

1. Diversity is the Best Defense

In the microbial world, specialization is a weakness; diversity is a superpower. A gut with only a few types of bacteria is fragile and prone to "overgrowth" by pathogens.

The Pearl: Aim for 30 different plant foods per week. This includes spices, seeds, nuts, and different colored vegetables. Each unique fiber type acts as a specific "key" that unlocks the growth of a different beneficial bacterial species.

2. Your Gut Has a Circadian Rhythm

Just like you, your microbes have a biological clock. They perform different functions during the day (metabolism and energy) versus the night (repair and barrier maintenance).

The Pearl: Limit late-night snacking. Giving your gut a "fasting window" of 12–14 hours overnight allows specific "housekeeping" bacteria, such as Akkermansia muciniphila, to clean the gut lining and strengthen your immune barrier without the distraction of incoming food.

3. Fiber is "Pre-Built" Medicine

We often think of fiber as just "bulk" to help with digestion, but it is actually a precursor to systemic drugs produced by your own body. When bacteria ferment fiber, they create Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate.

The Pearl: Think of your colon as a natural pharmacy. When you eat a high-fibre meal, you aren't just eating nutrients; you are providing the raw materials for your bacteria to manufacture anti-inflammatory "medication" that enters your bloodstream and calms your immune system.

4. The "Post-Antibiotic" Window is Critical

Antibiotics are life-saving, but act like a "forest fire" for your gut ecosystem. The weeks immediately following a course of antibiotics are when your gut is most "plastic" or moldable.

The Pearl: Treat the 30 days after antibiotics as a replanting phase. Focus heavily on fermented foods (such as kefir and sauerkraut) and prebiotic fibres (like onions, garlic, and bananas) to ensure the "good seeds" take root before less desirable species can claim the empty territory.

5. Movement is a "Microbial Massage"

As mentioned in Study 4, exercise changes your microbiome independently of diet. Physical activity increases blood flow to the gut and enhances intestinal motility, which helps "sort" the bacterial populations.

The Pearl: Consistency beats intensity for gut health. Regular, moderate movement—like a brisk 20-minute walk—helps maintain the "Goldilocks" speed of digestion: fast enough to prevent toxic buildup, but slow enough for your beneficial bacteria to extract and ferment every last nutrient.

The Gut Microbiome Connection: How Your Diet Shapes Your Health and Wellbeing

What Is the Gut Microbiome? Understanding the Basics

Your gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms living primarily in your large intestine. While "microbes" might sound intimidating, the reality is that most of these organisms are essential partners in maintaining your health.

Key facts about your gut microbiota:

Contains roughly 100 trillion microorganisms

Weighs approximately 2 kilograms (about 4.5 pounds)

Contains more bacterial cells than your own body has human cells

Produces compounds that directly influence brain function, immunity, and metabolism

The exciting news? Unlike your DNA, which you inherit, your gut microbiota composition is largely determined by your lifestyle choices—especially diet and exercise. This means you have genuine power to shape your microbial ecosystem for better health.

Study 1: The Comprehensive Overview – Nutrition and Health Integration

Sanz et al. (2025): Connecting Nutrition to Human Health Through the Gut Microbiome

This landmark review in Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology synthesizes current understanding of how your diet-microbiome relationship directly impacts health outcomes. The research emphasizes that nutritional science can no longer ignore the role of the gut microbiota as a critical mediator between food and health.

Key takeaways from this study:

The gut microbiome acts as a "metabolic organ" that processes nutrients and produces health-promoting compounds

Dietary patterns directly shape which beneficial bacteria thrive in your gut

Dysbiosis (imbalance in gut bacteria) is linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory conditions

Personalized nutrition approaches must consider individual microbiota composition

The gut-brain axis means your gut health influences mood, cognition, and mental health

This research validates what integrative health practitioners have long suspected: you can't optimize health through diet alone without considering your microbial partners. A diet that works wonderfully for one person may have different effects on another, partly because of differences in their gut bacterial communities.

Study 2: Emerging Insights into Diet and Microbes

Barb, Wallen et al. (2025): Emerging Research on Diet, Gut Microbes, and Health

This study in Nutrients examines the latest findings on how specific dietary components influence gut microbial populations. The research identifies which foods promote the growth of beneficial microbes and which dietary patterns lead to microbial dysbiosis.

Key takeaways from this study:

Fiber intake is the primary driver of beneficial bacteria diversity

Ultra-processed foods significantly reduce microbial diversity and promote pathogenic bacteria

Polyphenol-rich foods (berries, tea, dark chocolate, nuts) support health-promoting bacterial metabolites

Fermented foods directly introduce beneficial live microorganisms into your gut

The gut microbiota composition changes within days of dietary modifications

The encouraging news: your gut health is remarkably responsive. Within just a few days of improving your diet, you can begin shifting your microbial ecosystem toward a healthier composition. This isn't about perfection—it's about consistent, incremental improvements.

Study 3: The Role of Beneficial Bacteria and Optimal Diets

Kumar et al. (2025): Beneficial Gut Bacteria and Health-Promoting Diets

Published in Frontiers in Microbiology, this comprehensive analysis identifies specific beneficial bacteria strains and the dietary patterns that support their growth. The research moves beyond general recommendations to specify which probiotic bacteria matter most for different health outcomes.

Key takeaways from this study:

Bacteroides fragilis, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Akkermansia muciniphila are particularly important beneficial bacteria associated with good health

Prebiotic foods (foods that feed beneficial bacteria) are more important than probiotic supplements alone

Mediterranean-style diets and plant-based eating patterns best support optimal gut bacterial diversity

Personalized nutrition based on microbiota analysis can improve health outcomes more than generic dietary advice

The interaction between dietary metabolites and beneficial bacteria creates a feedback loop that either promotes or undermines health

Rather than chasing the latest trendy supplement, focus on feeding your existing beneficial bacteria through whole foods. Think of your gut microbiota as a garden—you want to provide the right conditions for the plants (beneficial bacteria) you want to grow.

Study 4: How Exercise Shapes Your Microbial Health

Reljic et al. (2025): Exercise-Driven Changes in Gut Microbial Metabolites

This pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials in Gut Microbes provides solid evidence that physical exercise directly improves the microbial metabolites your gut bacteria produce. Importantly, the benefits increase with exercise intensity.

Key takeaways from this study:

Regular exercise increases production of beneficial microbial metabolites, even without dietary changes

Higher-intensity exercise produces greater improvements in bacterial metabolite production than low-intensity activity

Sedentary lifestyles are associated with unfavorable gut microbiota composition

The combination of optimal diet and regular exercise creates synergistic benefits for gut health

Benefits appear within weeks of starting an exercise program

This research reveals that getting moving isn't just good for your muscles and heart—it's medicine for your gut bacteria. Even if your diet isn't perfect, adding exercise can meaningfully improve your gut microbial health. The combination of dietary improvements and physical activity creates the most powerful effect.

Study 5: The Power of Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Mukhopadhya & Louis (2025): Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health

This seminal review in Nature Reviews Microbiology explains the critical role of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—the chemical compounds your gut bacteria produce when they digest fiber. These molecules are essentially the currency of communication between your gut microbiota and your body.

Key takeaways from this study:

Short-chain fatty acids (primarily butyrate, propionate, and acetate) are produced when gut bacteria ferment dietary fiber

Butyrate specifically strengthens the intestinal barrier, reduces inflammation, and provides energy to your colon cells

SCFA deficiency is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and neurological conditions

Dietary fiber is the primary driver of SCFA production

The gut-derived SCFA signaling influences immune function, glucose metabolism, and even brain chemistry

When your beneficial gut bacteria digest fiber, they produce SCFAs that repair your gut lining, reduce inflammation throughout your body, and help regulate blood sugar. This is one of the primary mechanisms that explains why high-fibre diets protect against numerous chronic diseases.

Study 6: Mechanisms Linking SCFAs to Systemic Health

Zhao et al. (2025): Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Systemic Homeostasis

This comprehensive analysis in the Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism maps out the detailed mechanisms through which SCFA signaling influences virtually every major body system. The research reveals how microbial metabolites coordinate health at the systems level.

Key takeaways from this study:

Short-chain fatty acids regulate the intestinal barrier function, preventing "leaky gut" and systemic inflammation

SCFA signaling controls immune cell development and activation, influencing both infection resistance and autoimmune risk

Butyrate production directly influences metabolic health, improving insulin sensitivity and glucose control

Propionate and acetate regulate appetite hormones and energy expenditure through interaction with G-protein coupled receptors

SCFA production influences the gut-brain axis, affecting mood, cognition, and neurological health through multiple pathways

Think of short-chain fatty acids as chemical messengers that translate your dietary choices into health-promoting signals throughout your body. When you eat fiber-rich foods, you're not just feeding yourself—you're feeding your beneficial bacteria so they can feed your health back to you.

The Gut-Brain Axis: Beyond Digestion

One of the most revelatory findings from these studies is the gut-microbiota-brain axis. Your gut bacteria don't just influence digestion; they directly communicate with your brain through multiple pathways:

SCFA production affects neurotransmitter synthesis, particularly serotonin and GABA

Bacterial lipopolysaccharides can trigger or reduce neuroinflammation

Microbial metabolites influence the permeability of the blood-brain barrier

The vagus nerve provides direct neural communication between gut and brain

This explains why people with dysbiosis often experience anxiety, depression, brain fog, and poor concentration—and why improving gut health can dramatically improve mental clarity and emotional resilience.

Practical Strategies: Building Your Optimal Microbiota

Based on the research presented, here are evidence-based strategies to optimize your gut health:

Prioritize Dietary Fiber (25-38g daily)

Soluble fiber (oats, beans, apples) and insoluble fiber (vegetables, whole grains, seeds) feed your beneficial bacteria and promote SCFA production. Most Americans consume only 15g daily.

Eat the Rainbow: Polyphenol-Rich Foods

Include diverse plant polyphenols from berries, dark leafy greens, tea, coffee, dark chocolate, and nuts. These compounds are preferentially fermented by beneficial bacteria, producing powerful health-promoting metabolites.

Include Fermented Foods Regularly

Fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, miso, tempeh) provide live beneficial microorganisms and prebiotic compounds. Aim for at least one serving daily.

Reduce Ultra-Processed Foods

Processed foods high in added sugars, refined oils, and additives actively suppress microbial diversity and promote pathogenic bacteria. These foods are essentially antimicrobial agents for your microbiome.

Move Your Body Regularly

Exercise intensity matters for gut health. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity weekly, plus strength training.

Consider Your Individual Microbiota Profile

Emerging microbiota testing can identify your specific bacterial composition and guide personalized nutrition strategies. One-size-fits-all diets are becoming obsolete.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Do I need to take probiotic supplements?

A: Research suggests that prebiotic foods (foods that feed beneficial bacteria) are more important than probiotic supplements alone. Quality matters if you do supplement, but prioritize feeding your existing beneficial bacteria through whole foods first.

Q: How long does it take to see improvements in gut health?

A: Your gut microbiota composition can shift within days to weeks of dietary changes. However, measurable health improvements typically appear within 4-8 weeks as SCFA production increases and your intestinal barrier strengthens.

Q: Can I improve my gut health without changing my diet?

A: While exercise provides measurable benefits, the research shows that dietary changes are the primary driver of microbiota improvement. The combination of diet and exercise is most effective.

Q: What if I have a sensitive gut or food intolerances?

A: Start slowly with increases in fiber intake and introduce fermented foods gradually. Some people benefit from low-FODMAP diets initially while their beneficial bacteria adjust. A healthcare provider or registered dietitian can personalize this approach.

Q: Are there specific bacteria I should look for in testing?

A: Yes. Research highlights the importance of Bacteroides fragilis, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Akkermansia muciniphila. However, overall bacterial diversity is more important than any single species.

Q: Is the Mediterranean diet really the best?

A: The research strongly supports Mediterranean-style eating and plant-forward diets as optimal for microbial diversity and health outcomes. However, other whole-food-based dietary patterns that emphasize fiber, fermented foods, and polyphenols show similar benefits.

Key Takeaways: Your Microbiome Roadmap

Your gut microbiota is a dynamic ecosystem shaped primarily by diet and lifestyle—not your genetics.

Dietary fiber is foundational. It's the primary fuel for beneficial bacteria and essential for SCFA production.

Short-chain fatty acids are the bridge between your diet and systemic health, influencing immunity, metabolism, and brain function.

Microbial diversity matters more than any single bacteria. A varied diet supporting diverse microbial communities is your best strategy.

Exercise amplifies dietary benefits for gut health, with higher intensity producing greater improvements.

Personalization is the future. Individual microbiota composition varies, and optimal nutrition increasingly accounts for this variation.

Small, consistent changes work better than extreme measures. Sustainable dietary improvements compound over months and years.

You have more control than you think. Unlike many health factors, your microbiota composition responds rapidly to lifestyle choices you can make today.

The Future of Nutrition Science

The research presented here represents a paradigm shift in how we understand nutrition and health. We're moving from a model focused solely on macronutrients and micronutrients to one that recognizes the gut microbiota as a central mediator of health.

Emerging developments include:

Predictive microbiota testing that forecasts disease risk

SCFA-boosting therapeutics for inflammatory and metabolic disorders

Personalized nutrition algorithms based on individual microbiota profiles

Therapeutic microbiota modification for treating specific health conditions

Precision medicine approaches that integrate genomic, metabolomic, and microbiota data

The good news? You don't need to wait for advanced testing to benefit. The dietary and lifestyle strategies supported by current research work now and work well.

Your Next Steps: Start Today

The research is clear: your gut health is not fixed—it's a dynamic reflection of your daily choices. Every meal is an opportunity to nourish either beneficial bacteria or pathogenic ones.

This week, try one change:

Add a serving of fermented food daily

Increase your fiber intake by 5 grams

Take a 30-minute walk after meals

Swap one processed snack for a whole food alternative

This month, work toward:

25-38g of daily fiber from diverse sources

Regular exercise at moderate-to-vigorous intensity

At least one polyphenol-rich food with each meal

Processed food reduction to less than 10% of calories

This year, consider:

Microbiota testing to understand your unique profile

Working with a registered dietitian for personalized guidance

Building sustainable eating patterns that work with your lifestyle

Creating a support system with friends or family for accountability

Your gut microbiota holds the key to better energy, improved immunity, stable mood, clearer thinking, and reduced disease risk. The science is in. The power to optimize your microbial health is in your hands—starting with your very next meal.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Is Meat Actually Bad for Your Heart? Evidence from Latest Nutrition Science | DR T S DIDWAL

What’s New in the 2025 Blood Pressure Guidelines? A Complete Scientific Breakdown | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

5 Steps to Reverse Metabolic Syndrome: Diet, Habit, & Lifestyle Plan | DR T S DIDWAL

The Role of Cholesterol in Health and Disease: Beyond the "Bad" Label | DR T S DIDWAL

Lowering Cholesterol with Food: 4 Phases of Dietary Dyslipidemia Treatment | DR T S DIDWAL

High Triglyceride Levels: 5 New Facts to Help You Lower Your Risk | DR T S DIDWAL

The Best Dietary Fat Balance for Insulin Sensitivity, Inflammation, and Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Barb, J. J., & Wallen, G. R. (2025). Emerging research on the relationship between diet, gut microbes, and human health. Nutrients, 17(16), 2627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162627

Kumar, S., Mukherjee, R., Gaur, P., Leal, É., Lyu, X., Ahmad, S., Puri, P., Chang, C.–M., Raj, V. S., & Pandey, R. P. (2025). Unveiling roles of beneficial gut bacteria and optimal diets for health. Frontiers in Microbiology, 16, Article 1527755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1527755

Mukhopadhya, I., & Louis, P. (2025). Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and their role in human health and disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 23, 635–651. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-025-01183-w

Reljic, D., Hermann, H. J., Dieterich, W., Neurath, M. F., & Zopf, Y. (2025). Exercise improves gut microbial metabolites in an intensity-dependent manner: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gut Microbes, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2025.2579354

Sanz, Y., Cryan, J.F., Deschasaux-Tanguy, M. et al. (2025). The gut microbiome connects nutrition and human health. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 22, 534–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-025-01077-5

Zhao, Y., Chen, J., Qin, Y., Yuan, J., Yu, Z., Ma, R., Liu, F., & Zhao, J. (2025). Linking short-chain fatty acids to systemic homeostasis: Mechanisms, therapeutic potential, and future directions. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2025, Article 8870958. https://doi.org/10.1155/jnme/8870958