Does Saturated Fat Cause Heart Disease? What the Latest Science Really Says

Forget the old rules. New research reveals how saturated fat affects your metabolism based on your unique biology. Discover the truth about "very long-chain" fats and heart health

NUTRITION

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

12/25/202511 min read

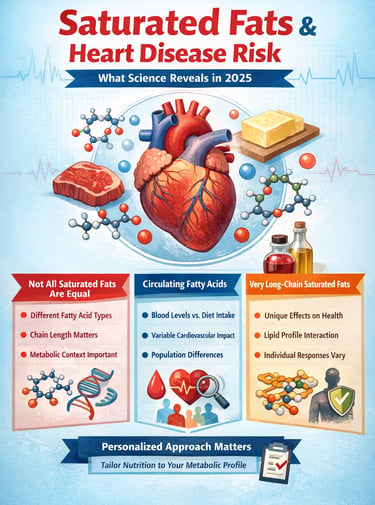

For many years, saturated fat was broadly labeled as harmful to heart health. However, modern research shows a far more nuanced reality. Recent high-quality studies demonstrate that not all saturated fats behave the same way in the body, and their effects depend on fatty-acid type, metabolic health, and individual risk factors (Dayrit, 2023; Szabó, 2025).

Large prospective studies now emphasize that circulating fatty acids—those measured in the blood—are more informative than dietary intake alone. These biomarkers better reflect how the body absorbs and processes fats and show varied associations with cardiovascular disease risk across populations (Shi et al., 2025). Importantly, emerging evidence highlights very long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCSFAs), which may have neutral or even protective effects depending on the broader lipid profile and metabolic context (Domínguez-López et al., 2025).

Intervention trials further reveal that reducing saturated fat does not benefit everyone equally. Cardiovascular outcomes depend strongly on baseline risk and on what replaces saturated fat in the diet—such as refined carbohydrates versus unsaturated fats (Steen et al., 2025).

Overall, current science supports a personalized approach to nutrition, focusing on metabolic markers like blood lipids, glucose control, and inflammation rather than strict universal limits. For most individuals, overall dietary quality and metabolic health matter far more than eliminating saturated fat entirely (Mizuno, 2025).

Clinical pearls

1. The "Lipid Context" Rule

The Science: Research from Domínguez-López (2025) shows that very long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCSFAs) aren't inherently "good" or "bad." Their impact is dictated by the other lipids (fats) present in your blood.

The Pearl: Think of saturated fat like a guest at a party. Whether they cause trouble depends on who else is in the room. If your overall lipid profile (HDL, triglycerides, and glucose) is healthy, your body likely handles saturated fat much more efficiently than if those markers are already out of range.

2. Blood Markers Over "Gram Counting"

The Science: Shi et al. (2025) emphasizes that circulating fatty acids—what is actually moving through your veins—predict heart health better than dietary logs.

The Pearl: Your body is a unique chemical processor. Two people can eat the same amount of butter, but their blood chemistry will look different based on genetics and activity. Instead of obsessing over the grams of fat on a nutrition label, prioritize regular blood panels to see how your specific "engine" is reacting to your fuel.

3. Baseline Risk Dictates the Strategy

The Science: The Steen et al. (2025) systematic review found that reducing saturated fat doesn’t provide a "universal" benefit. The positive impact was significantly higher for individuals who already had high cardiovascular risk.

The Pearl: Nutrition is not "one size fits all." If you are metabolically healthy and active, aggressive restriction of saturated fat may offer diminishing returns. However, if you have a family history of heart disease or high blood pressure, being more conservative with these fats remains a high-value move.

4. Chain Length Matters (Source Specificity)

The Science: Szabó (2025) highlights that saturated fats are a diverse family. Short, medium, and very long-chain fats have distinct metabolic pathways.

The Pearl: We need to stop grouping "steak fat," "coconut oil," and "whole-milk yogurt" into one bucket. For example, saturated fats found in fermented dairy (like yogurt or kefir) often show neutral or even protective effects on metabolism compared to the fats found in highly processed, shelf-stable snack foods.

5. The "Replacement" Effect

The Science: Multiple 2025 studies suggest that the health outcome of reducing saturated fat depends entirely on what you eat instead.

The Pearl: If you cut out saturated fat but replace it with refined starches or added sugars (like "low-fat" cookies), your metabolic health may actually decline. The goal isn't just to remove fat; it's to replace it with high-quality nutrients like monounsaturated fats (olive oil, avocados) or fiber-rich complex carbohydrates.

The Evolving Science of Saturated Fat

For decades, saturated fat was public enemy number one in nutrition discourse. Health organizations worldwide recommended dramatic reductions, often without distinguishing between different types of saturated fats or considering individual variations in metabolism. But recent scholarship suggests this one-size-fits-all approach may be oversimplified.

The relationship between saturated fat consumption and disease risk is far more complex than previously understood (Dayrit, 2023). Rather than categorical dismissal, modern evidence suggests we need to examine specific fatty acid types and how they interact with individual metabolic profiles. This shift reflects a fundamental change in how nutrition science conceptualizes fat's role in health.

As one editorial notes, there is "more than meets the label" when considering saturated fat and cardiovascular health (Mizuno, 2025). The implication is clear: the nutrition label doesn't tell the whole story about how saturated fats affect your body.

Understanding Dietary Fatty Acids and Metabolic Health

The most recent comprehensive review comes from Szabó (2025) in the journal Nutrients. This work, titled "Dietary Fatty Acids and Metabolic Health," provides an in-depth analysis of how different fatty acids influence metabolic processes.

Key Takeaways from Szabó (2025):

Fatty acid diversity matters: Not all saturated fats behave identically in the body

Metabolic context is crucial: Individual factors like insulin sensitivity, inflammation markers, and genetic predisposition influence how your body processes saturated fats (Szabó, 2025)

Chain length variations: Saturated fats with different carbon chain lengths have distinct metabolic effects

This research underscores a fundamental truth: when discussing dietary fatty acids and metabolic health, we're really discussing multiple substances with different properties, not a monolithic category.

Circulating Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

The largest and most recent analysis comes from Shi and colleagues (2025) in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. This groundbreaking study examined circulating fatty acids (the fats actually present in your bloodstream) and their relationship with cardiovascular disease risk by combining individual-level data from three large prospective cohorts alongside an updated meta-analysis.

Rather than all circulating fatty acids being equally problematic, research identifies that certain circulating fatty acids correlate differently with cardiovascular disease risk (Shi et al., 2025). This methodological rigor matters because it moves beyond simple correlations to examine real-world health outcomes across diverse populations.

Key Findings:

Specific fatty acids show differential associations: Different fatty acid profiles relate distinctly to cardiovascular outcomes

Population variation is real: Different demographic groups showed varying relationships between fatty acid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes

Assessment matters: How you measure fatty acid exposure affects conclusions about metabolic health

This research directly addresses a critical gap: most nutrition guidelines rely on dietary intake assessments, but what's absorbed and circulating in your blood tells a different story about actual metabolic health.

Very Long-Chain Saturated Fatty Acids: A Surprising Discovery

A specialized analysis by Domínguez-López and colleagues (2025) in Cardiovascular Diabetology focused on an often-overlooked category: very long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCSFAs) in plasma lipids.

Very long-chain saturated fatty acids are rarely discussed in mainstream nutrition conversations, yet research demonstrates they have unique effects on cardiometabolic risk (Domínguez-López et al., 2025). The critical finding? These effects don't occur in isolation—lipid interactions significantly influence whether VLCSFAs associate with increased or decreased disease risk.

Key Takeaways from Domínguez-López et al. (2025):

VLCSFAs have context-dependent effects: The relationship between these fats and cardiometabolic health depends heavily on the broader lipid profile

Lipid profiles are interconnected: You can't evaluate one type of fat in isolation

Individual variation is substantial: Some individuals showed protective associations, while others showed harmful ones

This finding explains why population averages don't apply uniformly—your unique lipid profile determines how your body responds to saturated fat intake

What are Very long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCSFAs)

Very long-chain saturated fatty acids (VLCSFAs) are a distinct subgroup of saturated fats containing 20 or more carbon atoms. Common examples include arachidic acid (C20:0), behenic acid (C22:0), and lignoceric acid (C24:0), which are found in foods such as peanuts, peanut butter, canola oil, and certain nuts and seeds. Unlike shorter-chain saturated fats, VLCSFAs are absorbed less efficiently and play important structural roles in cell membranes, nerve tissue (myelin), and sphingolipids.

Recent research suggests that VLCSFAs behave differently from traditional saturated fats like palmitic acid. Blood levels of VLCSFAs are influenced not only by diet but also by internal metabolic pathways, particularly fatty acid elongation. Importantly, several large observational studies show that higher circulating VLCSFAs are not consistently associated with increased cardiovascular risk and, in some metabolic contexts, may be linked to lower cardiometabolic risk markers.

Overall, VLCSFAs highlight why saturated fats should not be viewed as a single harmful category. Their health effects depend on fatty-acid type, metabolic health, and overall lipid profile rather than intake alone.

The Intervention Evidence: What Actually Changes Health Outcomes?

While observational data reveals associations, the ultimate question is: if people change their saturated fat intake, does health improve? Steen and colleagues (2025) tackled this question with a risk-stratified systematic review of randomized trials published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The Study Design:

This comprehensive review examined interventions aimed at reducing or modifying saturated fat intake and measured effects on multiple outcomes:

Cholesterol levels

Mortality rates

Major cardiovascular events

The innovation was risk stratification—analyzing whether interventions worked differently for people at different baseline risk levels.

Critical Findings from Steen et al. (2025):

Not all saturated fat reductions produce equal benefits: The effects of lowering saturated fat intake varied substantially based on baseline cardiovascular disease risk

Individual context determines outcomes: A strategy that helps one person may be neutral or even unfavorable for another

Intervention type matters: Whether people simply reduced saturated fat or replaced it with alternatives produced different results

This is perhaps the most important finding for practical nutrition: the blanket advice to "reduce saturated fat" may miss crucial personalization opportunities.

Key Themes Connecting Current Research

As we synthesize these five major 2025 research efforts, several themes emerge:

Complexity Over Simplicity

The days of categorical thinking about saturated fat are ending. Current science reveals that dietary fatty acids, their metabolism, their form in circulating lipids, and individual metabolic health profiles interact in sophisticated ways.

Individual Variation Is Real

Whether examining metabolic health outcomes, lipid interactions, or response to cardiovascular health interventions, individual differences are substantial. Genetic factors, existing health status, and lifestyle context all matter enormously.

Biomarkers Trump Assumptions

The shift from dietary questionnaires to actual circulating fatty acids measurement represents significant progress. What you actually absorb and circulate differs from what you eat, and your blood chemistry reveals your true metabolic status.

Type-Specific Effects

Very long-chain saturated fatty acids differ from medium-chain varieties; different fatty acid chain lengths produce different physiological effects. The specificity of modern research contrasts sharply with earlier blanket recommendations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should I do differently based on this research?

Focus on three evidence-based actions: First, monitor metabolic health markers (blood lipids, glucose control, inflammatory markers) rather than obsessing over absolute saturated fat numbers. Second, prioritize dietary fatty acid diversity—include omega-3s, monounsaturated fats, and yes, some saturated fats. Third, if you have cardiovascular disease risk factors, work with a healthcare provider on personalized nutrition strategies rather than following generic guidelines.

Are all saturated fats equally problematic?

No. The research clearly distinguishes between saturated fat types. Very long-chain saturated fatty acids behave differently than shorter varieties. Sources matter too—saturated fat from whole dairy differs from processed sources due to accompanying nutrients and compounds.

Should I eliminate saturated fat completely?

The evidence doesn't support elimination. Even the most recent cardiovascular health research acknowledges that complete avoidance may be neither necessary nor beneficial for many people. The key is finding your personal metabolic tolerance and focusing on overall dietary quality.

How do I know if saturated fat affects my metabolism negatively?

Request blood work measuring circulating fatty acids, inflammatory markers, and glucose control. These metabolic health biomarkers tell the real story better than dietary logs alone. If your lipid profile remains favorable despite saturated fat intake, aggressive restriction may be unnecessary.

Does the type of saturated fat source matter?

Absolutely. A butter-based food also provides fat-soluble vitamins and other nutrients. A processed food with added saturated fat contains additional problematic ingredients. The whole-food context matters as much as the fatty acid composition.

Can saturated fat reduction help my cardiovascular health?

It depends on your current metabolic health status and what you replace it with. According to Steen et al. (2025), benefits aren't universal. For some people, modest reductions combined with overall dietary quality improvements help. For others, the benefits are minimal. Personalization matters.

What's the difference between dietary fat intake and circulating fatty acids?

Your circulating fatty acids reflect not just what you eat but also what your body absorbs, synthesizes, and utilizes. Two people eating identical diets show different lipid profiles due to genetic and metabolic differences. Measuring circulating fatty acids provides objective data about your actual metabolic status.

Practical Recommendations: Beyond the Guidelines

Prioritize dietary diversity: Include saturated fats (perhaps 7–10% of calories), monounsaturated fats (10–15%), polyunsaturated fats including omega-3s, and avoid trans fats. Whole food sources—olive oil, nuts, fish, eggs, and yes, dairy—provide beneficial compounds alongside fats.

Monitor your metabolic markers: Annual blood work assessing circulating lipids, glucose control, and inflammation gives personalized insight unavailable from generic guidelines. These biomarkers reveal how your body actually responds.

Consider your baseline risk: If you have established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors, more conservative saturated fat intake (7–10% of calories) may be appropriate. If you're young and healthy with favorable metabolic health markers, current evidence supports greater flexibility.

Understand lipid interactions: Your lipid profile is interconnected. A diet raising beneficial HDL cholesterol while maintaining favorable LDL may be superior to one that simply minimizes total fat, even if saturated fat percentage is higher.

Assess individual tolerance: Notice how you feel on different dietary approaches. Some people thrive with higher saturated fat intake and minimal refined carbohydrates. Others benefit from lower saturated fat with emphasis on plant-based options. Personalized nutrition recognizes these differences.

The Future of Fat and Nutrition Science

The trajectory of research is clear: we're moving from categorical thinking toward precision nutrition. The era of "avoid saturated fat" is transitioning to "manage your individual metabolic health and lipid profile."

This represents tremendous progress. Rather than guilt-inducing restrictions, we're developing personalized strategies grounded in objective metabolic health data and individual physiology. The research from Szabó, Dayrit, Mizuno, Shi, Domínguez-López, and Steen collectively points toward this more sophisticated, evidence-based approach.

Ready to Optimize Your Nutrition?

The evidence is clear: your individual metabolic health matters far more than following one-size-fits-all guidelines. Rather than obsessing over saturated fat grams, focus on understanding your unique lipid profile, monitoring relevant metabolic health biomarkers, and working with nutrition professionals to develop strategies aligned with your physiology.

Get started by requesting comprehensive blood work assessing circulating lipids, inflammatory markers, and glucose control. This objective data about your actual metabolic status provides the foundation for truly personalized dietary decisions.

The latest research shows the path forward isn't elimination or obsession—it's informed personalization based on your body's unique response.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Rethinking Dietary Fats: What New Research Reveals About Plant vs. Animal Fats | DR T S DIDWAL

What’s New in the 2025 Blood Pressure Guidelines? A Complete Scientific Breakdown | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

5 Steps to Reverse Metabolic Syndrome: Diet, Habit, & Lifestyle Plan | DR T S DIDWAL

The Role of Cholesterol in Health and Disease: Beyond the "Bad" Label | DR T S DIDWAL

Lowering Cholesterol with Food: 4 Phases of Dietary Dyslipidemia Treatment | DR T S DIDWAL

High Triglyceride Levels: 5 New Facts to Help You Lower Your Risk | DR T S DIDWAL

The Best Dietary Fat Balance for Insulin Sensitivity, Inflammation, and Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Dayrit, F. M. (2023). Editorial: Saturated fat: metabolism, nutrition, and health impact. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, Article 1208047. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1208047

Domínguez-López, I., Eichelmann, F., Prada, M., et al. (2025). Very long-chain saturated fatty acids in plasma lipids: Association with cardiometabolic risk influenced by lipid interactions. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 24(1), Article 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-03037-4

Mizuno, A. (2025). There is more than meets the label: Rethinking saturated fat and cardiovascular health [Editorial]. JMA Journal, 8(2), 408–410. https://doi.org/10.31662/jmaj.2025-0120

Shi, F., Chowdhury, R., Sofianopoulou, E., Koulman, A., Sun, L., Steur, M., ... Kaptoge, S. (2025). Association of circulating fatty acids with cardiovascular disease risk: Analysis of individual-level data in three large prospective cohorts and updated meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 32(3), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae315

Szabó, É. (2025). Dietary fatty acids and metabolic health. Nutrients, 17(15), 2512. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152512

Steen, J. P., Klatt, K. C., Chang, Y., Guyatt, G. H., Zhu, H., Swierz, M. J., ... Johnston, B. C. (2025). Effect of interventions aimed at reducing or modifying saturated fat intake on cholesterol, mortality, and major cardiovascular events: A risk-stratified systematic review of randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.7326/ANNALS-25-02229