Beyond the Low-Fat Myth: 6 New Studies Redefining Dietary Fat and Heart Health

Is fat really bad for your heart? Explore 6 breakthrough studies redefining dietary fat, LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular risk.

NUTRITION

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/20/202617 min read

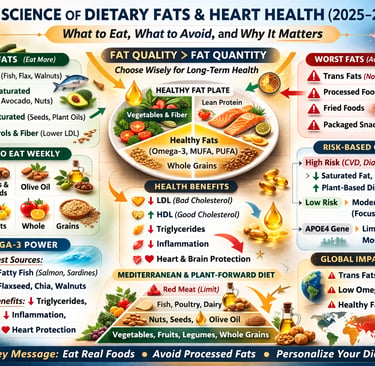

For decades, the conversation around dietary fat has swung between fear and fascination. Once blamed for everything from heart disease to obesity, fat was aggressively removed from supermarket shelves in the name of public health. But as we move into 2026, the science tells a very different story. The real question is no longer “Is fat bad?”—it’s which fats improve cardiovascular health, and which increase cardiometabolic risk?

Landmark analyses published in 2025–2026 have reshaped our understanding of saturated fat, unsaturated fats, omega-3 fatty acids, and their impact on LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and long-term mortality. A major risk-stratified systematic review in Annals of Internal Medicine found that reducing saturated fat may significantly benefit individuals at high cardiovascular risk, but offers less clear advantage in lower-risk populations (Steen et al., 2026). Meanwhile, global data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 highlight inadequate omega-3 intake as a growing contributor to coronary heart disease worldwide (Ma et al., 2025).

Emerging research also emphasizes that dietary patterns—not isolated nutrients—drive outcomes. A large prospective cohort study demonstrated that plant-forward, whole-food dietary patterns lower all-cause mortality among individuals with dyslipidemia (Yin et al., 2025). At the same time, updated clinical guidance now recommends Mediterranean-style diets as first-line therapy for lipid management (Patel et al., 2025).

In short, modern lipid science is no longer about eliminating fat—it’s about fat quality, metabolic individuality, and precision nutrition. Understanding the difference could redefine how you protect your heart, optimize your cholesterol, and reduce long-term cardiovascular risk.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Substitution" Rule

Scientific Perspective: Reducing saturated fatty acids (SFAs) only improves cardiovascular outcomes if they are replaced with polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) or complex carbohydrates. Replacing SFAs with refined starches or sugars (e.g., "low-fat" cookies) can actually increase triglycerides and worsen insulin resistance.

Don’t just "cut out" butter or meat. If you remove a fat, you must replace it with something better, like olive oil, walnuts, or salmon. If you replace fat with white bread or sugar, your heart risk stays the same or gets worse.

2. Risk-Based Restriction

Scientific Perspective: According to Steen et al. (2026), the "diet-heart" hypothesis is risk-stratified. Individuals with existing heart disease or multiple risk factors see significant mortality benefits from strict SFA reduction, whereas the benefit for low-risk, healthy individuals is statistically much smaller.

Dietary "strictness" isn't one-size-fits-all. If you have a history of heart issues, being very careful with saturated fat is a life-saving priority. If you are young and healthy, a moderate amount of high-quality saturated fat (like Greek yogurt) is likely fine.

3. The Omega-3 "Silent Deficiency"

Scientific Perspective: Ma et al. (2025) identified low omega-3 intake (EPA/DHA) as a top global mortality risk factor. Its benefits extend beyond just lowering triglycerides; it provides systemic anti-inflammatory effects and membrane stabilization.

Most people focus on what to avoid (bad fats), but it’s just as important to focus on what to include. Think of Omega-3s (from fatty fish or supplements) as "cellular armor" that protects your heart and brain.

4. The "Food Matrix" Over the Nutrient

Scientific Perspective: Yin et al. (2025) demonstrated that dietary patterns (like the Mediterranean or plant-forward diets) are better predictors of longevity than any single gram-count of fat. The synergy of fiber, polyphenols, and fats in whole foods modulates lipid absorption.

Stop counting "fat grams" on a calculator. If your plate is full of vegetables, legumes, and nuts, the specific percentage of fat matters much less than the fact that you’re eating "real food" rather than processed "food products."

5. Genetic Individuality (The APOE Factor)

Scientific Perspective: As highlighted by Lovegrove (2025), genetic polymorphisms like the APOE4 allele significantly dictate how a person’s LDL-cholesterol responds to dietary fat. Two people eating the same steak can have vastly different blood-work results based on their DNA.

If your cholesterol stays high despite a "perfect" diet, it’s not a moral failure—it might be your genetics. Personalized nutrition means your body may require a different strategy than your neighbor’s, even if they are the same age and weight.

6. The "Trans Fat" Zero Tolerance

Scientific Perspective: There is no "safe" threshold for industrially produced trans fats (partially hydrogenated oils). They are uniquely toxic, simultaneously raising "bad" LDL while lowering "good" HDL and triggering systemic inflammation.

While the debate on saturated fat is nuanced, the debate on trans fat is over. If a label says "partially hydrogenated," it should be considered a toxin, not a food. It is the only fat where the goal is 0%.

Part 1: Understanding Lipids — The Building Blocks of the Conversation

Before diving into the research findings, it helps to understand what lipids actually are and why they matter so profoundly in clinical nutrition.

Lipids are a broad class of fat-soluble molecules that include triglycerides, phospholipids, sterols (such as cholesterol), and free fatty acids. They are not merely stored energy — they are fundamental to cell membrane integrity, hormone synthesis, fat-soluble vitamin absorption (A, D, E, and K), and inflammatory regulation. Without adequate dietary fat, human physiology simply cannot function optimally.

According to Frydrych et al. (2025), dietary lipids play critical roles in inflammation modulation, immune function, and the structural maintenance of every cell in the body. Their narrative review emphasizes that lipid quality — not just quantity — determines whether dietary fat contributes to health or disease. Saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and trans fatty acids all interact with biological systems in distinct ways, making a blanket recommendation to "reduce fat" both overly simplistic and potentially counterproductive.

The conversation, then, is not about whether to eat fat. It is about which fats, in what amounts, and in what dietary context.

Part 2: Saturated Fat, Cholesterol, and Cardiovascular Risk — Revisiting the Evidence

Perhaps no dietary topic has generated more scientific controversy in recent years than the relationship between saturated fat intake, LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. The traditional diet-heart hypothesis — that dietary saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol, which in turn increases risk of major cardiovascular events — has been the cornerstone of dietary guidelines since the 1960s. But a major 2026 systematic review has complicated that picture significantly.

Steen et al. (2026) published a risk-stratified systematic review in the Annals of Internal Medicine examining randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested interventions aimed at reducing or modifying saturated fat intake. Their analysis, which included data from numerous trials and accounted for individual cardiovascular risk stratification, found that the effects of reducing or modifying saturated fat were not uniform across populations. Crucially, when trials were stratified by baseline cardiovascular risk, the benefit of saturated fat reduction on mortality and major cardiovascular events was most evident in higher-risk individuals — and less clear or clinically meaningful in those at lower baseline risk.

This finding has significant implications for how dietary fat recommendations are applied in practice. A blanket policy of saturated fat restriction may be appropriate for individuals with established CVD or multiple risk factors, but may offer little net benefit — and potentially some harms through unintended dietary substitutions — in the general, lower-risk population.

The cholesterol-lowering effect of replacing SFAs with carbohydrates, for instance, depends heavily on which carbohydrates are substituted. Replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates and added sugars does not improve cardiovascular outcomes and may worsen triglyceride profiles and insulin sensitivity. Replacing SFAs with unsaturated fats — particularly PUFAs — remains the most evidence-supported substitution for reducing CVD risk at the population level.

Part 3: From Population Guidelines to Personalized Nutrition — Closing the Gap

One of the most compelling themes emerging from recent dietary fat research is the growing tension between population-level dietary guidelines and the biological reality of individual variation. Lovegrove (2025), writing in Nutrition Bulletin, framed this tension elegantly in a paper exploring dietary fats and cardiometabolic health through the lens of both public health and personalized nutrition.

Lovegrove's review argued that traditional dietary guidelines — built on average population responses to dietary changes — often fail to capture the enormous inter-individual variability in how people respond to different types and amounts of dietary fat. Genetic polymorphisms (such as variations in the APOE gene), gut microbiome composition, metabolic phenotype, sex, age, and baseline cardiometabolic risk all modulate how dietary fat affects lipid profiles and cardiovascular outcomes.

The concept of a "one-size-fits-all" dietary fat recommendation is increasingly untenable in light of this evidence. Lovegrove (2025) advocated for a dual-track approach: maintaining robust population-level guidance to shift the average dietary pattern away from harmful fats (particularly industrial trans fats and excessive SFAs in low-nutritional-quality food contexts), while simultaneously investing in personalized nutrition strategies that account for individual phenotype and genotype.

This is not merely an academic argument. Clinically, it means that a person with the APOE4 genotype — a known genetic risk factor for hyperlipidemia and Alzheimer's disease — may respond more adversely to a high saturated fat diet than someone with a different genotype, even if both individuals follow the same dietary pattern. Precision nutrition tools, including genetic testing and metabolomic profiling, are beginning to make individualized dietary fat guidance a clinical reality rather than a theoretical aspiration.

Part 4: Dietary Patterns, Dyslipidemia, and Mortality — Lessons From a Prospective Cohort

While mechanistic and intervention studies tell us how dietary fats affect biology, prospective cohort studies help us understand who lives longer based on what they eat in the real world. Yin et al. (2025) provided exactly this kind of evidence in a large prospective cohort study conducted in Guizhou Province, China.

Their study examined dietary patterns and the risk of all-cause mortality in individuals with dyslipidemia — a population that is already at elevated risk for cardiovascular events, metabolic disease, and premature death. The researchers identified distinct dietary patterns through statistical clustering and found that dietary patterns higher in plant foods, whole grains, legumes, and fish were associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality risk compared to patterns characterized by high intakes of refined carbohydrates, processed meats, and fried foods.

These findings align with a broader global literature showing that overall dietary pattern quality — rather than any single nutrient in isolation — is the strongest dietary predictor of long-term health outcomes. For individuals with dyslipidemia in particular, this suggests that the clinical focus should not be limited to lipid-modifying medications and isolated nutrient targets (such as dietary cholesterol or total fat grams), but should encompass the entire dietary landscape: food variety, dietary diversity, food processing levels, and the synergistic effects of nutrients consumed together.

Importantly, Yin et al. (2025) found that their results held even after adjusting for confounding variables including physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, and socioeconomic factors — strengthening the causal plausibility of the dietary pattern-mortality relationship in dyslipidemia populations.

Part 5: The Global Burden of Dietary Fat — Comprehensive Meta-Analytic Evidence

To contextualize individual studies within the global burden of diet-related disease, Ma et al. (2025) published a comprehensive review of meta-analyses alongside Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 data in Trends in Food Science & Technology. Their paper examined how dietary fat and fatty acid consumption patterns at the population level contribute to disease burden worldwide.

The analysis revealed a striking global asymmetry: while excessive intake of saturated and trans fats remains a significant contributor to cardiovascular disease burden in high-income countries, deficiencies of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (particularly EPA and DHA from marine sources) represent a growing and underappreciated risk factor globally. Low omega-3 intake was associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality across multiple meta-analyses reviewed by Ma and colleagues.

Trans fatty acids — specifically industrially produced trans fats found in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils — were consistently identified across meta-analyses as the most harmful type of dietary fat, with no safe threshold of consumption. The scientific consensus on industrial trans fats is unusually unequivocal: their complete elimination from the food supply is both justified and achievable, as demonstrated by countries that have successfully implemented legislative bans.

The GBD data further highlighted that the dietary fat risk landscape varies significantly by region, socioeconomic status, and food system context. In low- and middle-income countries, improving access to high-quality unsaturated fats (through increased availability of nuts, seeds, fish, and plant oils) may represent a higher-yield public health intervention than saturated fat reduction per se. This regional nuance underscores the need for context-sensitive dietary fat policy rather than universal prescriptions.

Part 6: Clinical Management of Dyslipidemia — Updated 2025 Guidelines

For healthcare providers managing patients with dyslipidemia, the 2025 consensus statement from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) provides a comprehensive, evidence-grounded algorithm for clinical decision-making. Patel et al. (2025) authored this updated guideline, which integrates the latest evidence on pharmacological and lifestyle-based lipid management strategies.

Key updates in the 2025 AACE algorithm include a stronger emphasis on cardiovascular risk stratification as the primary driver of treatment intensity. Rather than treating lipid numbers in isolation, the guideline recommends a holistic risk-based approach that considers 10-year cardiovascular risk score, presence of comorbidities, genetic dyslipidemias (such as familial hypercholesterolemia), and patient-specific factors including medication tolerability and adherence.

On the dietary side, the consensus statement affirms the primacy of Mediterranean-style and plant-forward dietary patterns for lipid management, citing their consistent association with favorable changes in LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and inflammatory markers. Specific dietary recommendations include replacing saturated fats with MUFAs and PUFAs, increasing dietary fiber intake (particularly soluble fiber), and limiting added sugars and ultra-processed foods.

The guideline also acknowledges the emerging evidence on specific functional foods and nutraceuticals — including plant sterols and stanols, omega-3 fatty acid supplements, and red yeast rice — as adjunctive tools in lipid management for patients who cannot achieve targets through diet alone or who are intolerant of statin therapy. However, it cautions that the evidence base for nutraceuticals remains less robust than for pharmacological lipid-lowering therapy, and that their use should be individualized and monitored.

Part 7: Omega-3 Fatty Acids — The Most Underutilized Tool in Cardiometabolic Health

Across multiple studies reviewed here, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids — particularly the long-chain marine-derived EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) — emerge as among the most consistently beneficial dietary fats for cardiometabolic health.

Frydrych et al. (2025) described the anti-inflammatory, triglyceride-lowering, and cardioprotective mechanisms of omega-3 fatty acids in detail. Ma et al. (2025) quantified the global mortality burden attributable to inadequate omega-3 intake. Patel et al. (2025) included high-dose omega-3 supplementation (specifically icosapentaenoic acid) among the pharmacologically active lipid-lowering options for high-risk patients with elevated triglycerides, supported by landmark cardiovascular outcomes trials.

Yet population-level omega-3 intake remains chronically below recommended levels in most countries. The practical implication is clear: increasing consumption of fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines, herring), as well as plant-based ALA-rich foods (flaxseeds, chia seeds, walnuts), and considering supplementation in high-risk individuals, represents one of the most evidence-supported dietary fat interventions available.

Part 8: Practical Dietary Fat Recommendations — Translating Evidence to the Plate

The End of the Low-Fat Dogma

For decades, public health messaging equated all dietary fat with danger. This oversimplified narrative fueled the low-fat, processed-food era—often replacing fat with refined carbohydrates. Today, robust evidence confirms that the quality of fat, not total fat alone, determines its impact on atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and long-term cardiovascular mortality.Fat Quality Over Quantity

The metabolic effects of fat depend on structure. Monounsaturated fats (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fats (PUFA)—especially omega-3 fatty acids—improve lipid profiles, reduce triglycerides, and modulate inflammatory pathways. In contrast, industrial trans fats consistently increase LDL cholesterol, systemic inflammation, and coronary risk. The clinical conversation must shift from restriction to intelligent substitution.Saturated Fat: Context Matters

Saturated fat is neither absolved nor universally condemned. Its effect varies by food matrix, background diet, and patient risk profile. Replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates offers no benefit. However, replacing it with unsaturated fats improves lipoprotein particle dynamics and lowers cardiovascular risk in high-risk individuals. Precision, not polarization, is required.Dietary Patterns Drive Outcomes

Nutrients do not act in isolation. The Mediterranean-style diet, rich in olive oil, nuts, legumes, fatty fish, and plant polyphenols, consistently demonstrates reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events. Whole-food, plant-forward dietary patterns outperform reductionist nutrient counting in real-world prevention strategies.Omega-3 as Therapeutic Nutrition

Marine-derived omega-3 fatty acids provide measurable reductions in triglycerides and may improve endothelial function. In selected high-risk populations, targeted omega-3 strategies complement pharmacotherapy, reinforcing the concept of food as metabolic intervention.Dyslipidemia Management Beyond Statins

While statins remain foundational in lipid management, lifestyle architecture determines residual risk. Replacing saturated fat (SFA) with PUFA/MUFA, increasing dietary fiber, and eliminating trans fats produce synergistic benefits. Pharmacology without nutrition reform is incomplete medicine.Inflammation and Metabolic Resilience

Modern lipid science recognizes inflammation as central to plaque instability. Diets abundant in unsaturated fats, antioxidants, and phytonutrients reduce inflammatory signaling, improving both vascular integrity and metabolic flexibility.Global Health Imperative

Low intake of omega-3 and continued trans fat exposure remain global public health failures. Policy reform, food labeling transparency, and physician-led nutrition literacy are essential to reverse preventable cardiometabolic deaths.Precision Nutrition Is the Future

Genetic variability, microbiome diversity, insulin sensitivity, and baseline lipid phenotype influence dietary response. The future of lipidology lies in individualized dietary prescriptions rather than universal fat caps.The Bottom Line

The debate is no longer “fat versus no fat.” It is inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory nutrition, refined versus whole-food patterns, and passive risk acceptance versus proactive metabolic stewardship. The science is clear: strategic fat selection is a cornerstone of 21st-century cardiovascular prevention.

Key Takeaways From Each Study

Study 1 — Frydrych et al. (2025): Lipids in Clinical Nutrition

Key Takeaway: Dietary lipids are biologically indispensable and their health effects are determined far more by type than by quantity. Saturated fats, MUFAs, PUFAs, and trans fats each interact with the body in fundamentally different ways, making nuanced, fat-specific guidance essential in clinical nutrition practice. This narrative review provides a strong foundation for understanding why "low-fat" as a blanket recommendation is scientifically outdated.

Study 2 — Steen et al. (2026): Saturated Fat Interventions — A Risk-Stratified Systematic Review

Key Takeaway: Reducing or modifying saturated fat intake does not benefit all individuals equally. The cardiovascular benefit of saturated fat reduction is most pronounced in people at high baseline cardiovascular risk. For lower-risk populations, the magnitude of benefit is less clear, and the quality of the replacement macronutrient — whether unsaturated fat or refined carbohydrate — critically determines whether any benefit is realized at all.

Study 3 — Lovegrove (2025): Dietary Fats and Cardiometabolic Health — Personalized Nutrition

Key Takeaway: The future of dietary fat guidance lies at the intersection of population-level public health messaging and precision nutrition. Genetic variation, gut microbiome differences, sex, and metabolic phenotype create enormous inter-individual variability in dietary fat response. Effective dietary fat strategies must eventually incorporate personal biology rather than relying solely on average population responses.

Study 4 — Yin et al. (2025): Dietary Patterns and Mortality in Dyslipidemia

Key Takeaway: For individuals with dyslipidemia, dietary pattern quality — not isolated nutrient intake — is the most powerful dietary predictor of long-term survival. Plant-forward, whole-food dietary patterns are associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality in this high-risk population, even after controlling for lifestyle confounders. This reinforces the clinical importance of dietary counseling alongside pharmacological management in dyslipidemia care.

Study 5 — Patel et al. (2025): AACE Consensus Statement on Dyslipidemia Management

Key Takeaway: The 2025 AACE algorithm marks a meaningful evolution in dyslipidemia management by centering cardiovascular risk stratification rather than lipid numbers alone. Mediterranean and plant-forward dietary patterns are now formally affirmed as first-line lifestyle interventions. The guideline also acknowledges nutraceuticals as potential adjunct tools, while maintaining the primacy of evidence-based pharmacotherapy for high-risk patients.

Study 6 — Ma et al. (2025): Dietary Fat, Meta-Analyses, and Global Burden of Disease

Key Takeaway: The global burden of dietary fat-related disease is both enormous and preventable. Industrial trans fats carry no safe threshold and should be eliminated globally. Low omega-3 intake is a criminally underappreciated risk factor for cardiovascular mortality worldwide. Regional and socioeconomic context must inform dietary fat policy, with solutions tailored to local food systems and nutritional deficiencies rather than applied uniformly across all populations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Is saturated fat really bad for you?

The honest answer is: it depends. Saturated fat is not inherently toxic, but consuming it in large amounts — particularly from low-quality processed food sources — can raise LDL cholesterol and increase cardiovascular risk, especially in people who are already at elevated risk. However, as Steen et al. (2026) demonstrated, the cardiovascular benefit of reducing saturated fat is most meaningful for high-risk individuals. For lower-risk healthy adults, moderate saturated fat intake as part of an overall high-quality dietary pattern is unlikely to cause harm, particularly when the broader diet is rich in vegetables, fiber, and unsaturated fats.

FAQ 2: What are the best dietary fats for heart health?

The most consistently evidence-supported fats for cardiovascular health are unsaturated fats — specifically monounsaturated fatty acids (found in olive oil, avocados, and nuts) and polyunsaturated fatty acids, including omega-3s (from fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts) and omega-6s (from vegetable oils). These fats favorably influence LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and inflammatory markers when substituted for saturated and trans fats.

FAQ 3: Should I avoid fat if I have high cholesterol or dyslipidemia?

Not necessarily. Avoiding fat is not the same as improving your lipid profile. As Yin et al. (2025) found, what matters most for long-term outcomes in dyslipidemia is overall dietary pattern quality — specifically, emphasizing plant-based whole foods, lean protein, and healthy fats while reducing ultra-processed foods and refined carbohydrates. Work with your healthcare provider using the 2025 AACE guidelines (Patel et al., 2025) to develop a personalized strategy that combines dietary changes with appropriate medical management.

FAQ 4: Are omega-3 supplements worth taking?

For most healthy people who consume fatty fish regularly, additional supplementation may not be necessary. However, for individuals with elevated triglycerides, high cardiovascular risk, or insufficient dietary omega-3 intake, evidence supports omega-3 supplementation — particularly high-dose prescription EPA formulations, which have demonstrated cardiovascular benefit in major clinical trials. Ma et al. (2025) and Patel et al. (2025) both underscore the therapeutic relevance of omega-3s, particularly for high-risk patients. Discuss with your doctor before starting supplementation.

FAQ 5: How does my genetics affect how I respond to dietary fat?

Significantly. Lovegrove (2025) highlights that genetic variants — particularly in genes like APOE, APOA1, LPL, and others involved in lipid metabolism — can dramatically alter how an individual's lipid profile responds to changes in dietary fat intake. For instance, APOE4 carriers tend to show more pronounced LDL cholesterol increases in response to saturated fat consumption than non-carriers. As genetic testing becomes more accessible and affordable, personalized dietary fat advice based on genetic risk profiling is increasingly feasible and clinically valuable.

FAQ 6: Is a Mediterranean diet the best dietary pattern for managing lipids?

Among the dietary patterns with the strongest evidence base for cardiometabolic benefit, the Mediterranean-style diet — characterized by high intakes of vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, nuts, olive oil, and moderate red wine, with limited red meat and dairy — consistently outperforms most alternatives in clinical trials and cohort studies. Patel et al. (2025) formally endorse this pattern in the updated AACE dyslipidemia guidelines. That said, plant-forward whole-food patterns more broadly (including DASH, Portfolio, and plant-based diets) also demonstrate robust lipid-lowering effects and may be more accessible or culturally appropriate for many individuals.

FAQ 7: What are the worst dietary fats I should eliminate from my diet?

The clear answer across all studies reviewed here is industrially produced trans fats — found in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils and many processed, fried, and baked goods. These fats simultaneously raise LDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol, increase inflammation, and have no safe minimum intake. Ma et al. (2025) describe the global disease burden attributable to trans fat consumption as avoidable and call for complete elimination. Beyond trans fats, large amounts of saturated fat from highly processed sources (such as fast food, processed meat, and commercially baked products) should be minimized, particularly for individuals with existing cardiovascular risk factors.

Author’s Note

As a physician trained in internal medicine, I have watched the dietary fat debate evolve from rigid low-fat dogma to a far more nuanced, evidence-driven understanding of lipid metabolism and cardiometabolic health. For decades, patients were told to fear fat indiscriminately. Yet in clinical practice, I repeatedly observed that outcomes depended not on the absolute avoidance of fat, but on fat quality, overall dietary pattern, metabolic context, and cardiovascular risk profile.

This article was written to bridge the gap between rapidly advancing scientific literature and practical clinical application. Every conclusion presented here is grounded in recent peer-reviewed research (2025–2026), including systematic reviews, prospective cohort studies, global burden analyses, and updated consensus guidelines. My goal is not to promote dietary extremes, but to encourage evidence-based decision-making rooted in physiology, risk stratification, and personalized care.

Nutrition science is complex. It evolves. And it demands intellectual humility. As clinicians and informed readers, we must resist oversimplified narratives—whether they demonize saturated fat or romanticize any single dietary pattern. Instead, we must evaluate the totality of evidence while recognizing inter-individual variability in response to dietary fat.

If this article accomplishes one thing, I hope it helps readers move beyond fear-based messaging and toward a thoughtful, biologically informed approach to heart health, dyslipidemia management, and long-term metabolic resilience.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Can Plant-Based Polyphenols Lower Biological Age? | DR T S DIDWAL

Time-Restricted Eating: Metabolic Advantage or Just Fewer Calories? | DR T S DIDWAL

Can You Revitalize Your Immune System? 7 Science-Backed Longevity Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Exercise and Longevity: The Science of Protecting Brain and Heart Health as You Age | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Frydrych, A., Kulita, K., Jurowski, K., & Piekoszewski, W. (2025). Lipids in clinical nutrition and health: Narrative review and dietary recommendations. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 14(3), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14030473

Lovegrove, J. A. (2025). Dietary fats and cardiometabolic health—from public health to personalised nutrition: 'one for all' and 'all for one'. Nutrition Bulletin, 50(1), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12722

Ma, J., Hu, D., Li, D., Chen, Y., Chen, Q., Fan, Z., Wang, G., Xu, W., Zhu, G., Xin, Z., Cao, W., Zhang, Z., Wu, J., Ding, J., Yin, L., Chang, Y., & Ren, S. (2025). The impact of dietary fat and fatty acid consumption on human health: A comprehensive review of meta-analyses and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 160, 105002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.105002

Patel, S. B., Belalcazar, L. M., Afreen, S., Balderas, R., Hegele, R. A., Karpe, F., Ponte-Negretti, C. I., & Rajpal, A. (2025). American Association of Clinical Endocrinology consensus statement: Algorithm for management of adults with dyslipidemia — 2025 update. Endocrine Practice: Official Journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 31(10), 1207–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2025.07.014

Steen, J. P., Klatt, K. C., Chang, Y., Guyatt, G. H., Zhu, H., Swierz, M. J., Storman, D., Sun, M., Zhao, Y., Ge, L., Thabane, L., Ghosh, N. R., Karam, G., Alonso-Coello, P., Bala, M. M., & Johnston, B. C. (2026). Effect of interventions aimed at reducing or modifying saturated fat intake on cholesterol, mortality, and major cardiovascular events: A risk stratified systematic review of randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine, 179(2), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.7326/ANNALS-25-02229

Yin, L., Yu, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2025). Dietary patterns and risk of all-cause mortality in individuals with dyslipidemia based on a prospective cohort in Guizhou China. Scientific Reports, 15, 7395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88101-5