Why Metabolic Flexibility May Be the Missing Link in Longevity and Healthy Aging

Metabolic flexibility is the foundation of healthy aging. Learn how fuel switching protects longevity, prevents disease, and restores metabolic resilience.

AGINGMETABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/6/202616 min read

Modern medicine often treats metabolism as a static equation—calories in versus calories out, glucose high versus glucose low. Yet this reductionist view fails to explain a fundamental observation seen daily in clinical practice: two individuals with similar diets, body weight, and activity levels can display dramatically different energy profiles, disease trajectories, and aging patterns. Increasingly, evidence suggests that the missing variable is not how much energy the body has, but how adaptively it can use it—a property now known as metabolic flexibility (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

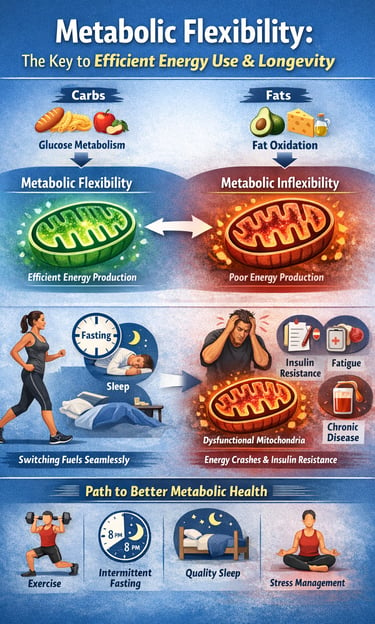

Metabolic flexibility describes the body’s capacity to dynamically shift between carbohydrate and fat oxidation in response to changing fuel availability, hormonal signals, and energetic demands. In healthy physiology, this switching is seamless and largely invisible. In pathological states, however, this adaptability erodes long before overt disease manifests, creating a silent period of metabolic vulnerability characterized by fatigue, insulin resistance, and impaired mitochondrial function (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

Emerging research reframes metabolic inflexibility not as a consequence of obesity or aging, but as a primary pathophysiological driver underlying cardiometabolic disease, neurodegeneration, and accelerated aging (Smith et al., 2018; Ang et al., 2025). Understanding metabolic flexibility therefore represents more than a theoretical advance—it offers a unifying framework for prevention, early intervention, and longevity-focused care.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Mitochondrial Traffic Jam" (Substrate Competition)

Metabolic inflexibility is often characterized by substrate competition at the mitochondrial level, where the inability to switch from glucose to lipid oxidation leads to the accumulation of intramyocellular lipids and metabolic intermediates. This "congested" state impairs the translocation of GLUT4, further exacerbating insulin resistance.

Think of your metabolism like a hybrid car that’s stuck in "gas mode" and can’t switch to "electric." When you eat too often, your cells get a "traffic jam" of fuel. By giving your body breaks from eating, you clear the road so your cells can switch between burning sugar and burning fat smoothly.

2. Post-Prandial Somnolence as a Diagnostic Signal

The "afternoon slump" serves as a clinical marker for impaired glucose-fatty acid cycle (Randle Cycle) efficiency. Inflexibility manifests as a failure to transition to lipid-derived ATP production as circulating post-prandial glucose levels decline, leading to a transient cellular "energy crisis."

That "food coma" or energy crash after lunch isn't just "being tired"—it’s a signal that your body is struggling to find its next fuel source. Improving your metabolic flexibility is like upgrading your battery so you stay powered up even when you haven't had a snack in a few hours.

3. Muscle as a "Metabolic Sponge"

Skeletal muscle accounts for approximately 80% of post-prandial glucose disposal. Sarcopenia or muscle quality degradation reduces the available surface area for insulin-mediated nutrient uptake, making lean mass preservation the most effective intervention for expanding the body's "metabolic buffer."

Your muscles are like a sponge for the sugar in your blood. The more muscle you have—and the more active those muscles are—the bigger your "sponge" becomes. This protects you from the damage high blood sugar can cause to your heart and nerves.

4. Circadian Rhythm and Fuel Choice

Metabolic flexibility is inherently circadian. Nocturnal melatonin secretion and the dip in core body temperature are coupled with a physiological shift toward lipid oxidation. Sleep fragmentation disrupts this rhythm, forcing a state of "metabolic rigidity" characterized by elevated fasting cortisol and nocturnal glucose reliance.

our body is programmed to burn fat while you sleep. However, if you stay up late or eat right before bed, you "trick" your body into staying in sugar-burning mode. Good sleep is literally a workout for your metabolism, helping you wake up as a more efficient fat-burner.

5. Training the "Metabolic Switch" via TRE

Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) functions as a non-pharmacological AMPK activator. By extending the fasted window to 12–14 hours, we induce an "autophagic reset" and force the upregulation of enzymes involved in beta-oxidation, thereby "training" the mitochondrial machinery to access endogenous fat stores.

You don't always need to eat less; sometimes you just need to eat less often. Closing the kitchen after dinner gives your body the 12 hours it needs to practice "digging into the archives" of your stored fat for energy. It’s like exercise for your internal fat-burning engine.

Metabolic Flexibility: The Key to Efficient Energy Use and Longevity

At its core, metabolic flexibility is your body's capacity to shift between carbohydrate and fat oxidation based on substrate availability and physiological demands (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017). In simpler terms, it's your metabolic system's versatility—the ability to use whatever fuel source is most readily available or appropriate for the situation.

When you eat a meal rich in carbohydrates, your body preferentially uses glucose for energy. When you're fasting or engaging in prolonged exercise on limited carbohydrate availability, your body efficiently switches to fat oxidation, breaking down stored triglycerides for fuel. This seamless transition is metabolic flexibility in action.

The concept extends beyond whole-body energy management. Recent research highlights the importance of tissue-specific metabolic flexibility—different organs and tissues have distinct metabolic capabilities and requirements. Your brain primarily uses glucose but can adapt to ketones during fasting states. Your skeletal muscles display remarkable flexibility, shifting between glucose and fat utilization. Your liver orchestrates much of this metabolic switching through gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis.

The inverse phenomenon, metabolic inflexibility, occurs when your body struggles to efficiently transition between fuel sources (Shoemaker et al., 2023). This metabolic dysfunction represents a fundamental departure from optimal physiology, with significant consequences for health and disease development.

The Science Behind Metabolic Flexibility

Understanding metabolic flexibility requires diving into the molecular mechanisms that regulate energy production. At the mitochondrial level, your cells contain specialized machinery for both carbohydrate and fat metabolism. The efficiency with which these systems function determines your overall metabolic flexibility (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

When your body possesses high metabolic flexibility, several positive cascades occur: insulin sensitivity improves, inflammatory markers decrease, antioxidant defenses strengthen, and mitochondrial function becomes more efficient. Conversely, metabolic inflexibility—the inability to smoothly transition between fuel sources—characterizes many chronic disease states (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

One fascinating aspect is how metabolic flexibility involves multiple regulatory pathways. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, the SIRT1 pathway, and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) family of receptors all coordinate to facilitate fuel switching. When these systems work harmoniously, your body can adapt to virtually any metabolic challenge.

The Pathophysiology of Metabolic Dysfunction

Recent investigations into the underlying mechanisms reveal that metabolic inflexibility serves as a critical pathological mechanism in numerous disease states. Research indicates that metabolic dysfunction develops through progressive deterioration in the capacity to oxidize fat, coupled with excessive reliance on glucose metabolism regardless of nutritional availability (Shoemaker et al., 2023). This creates a paradoxical situation where the body accumulates fat while simultaneously losing the ability to mobilize it for energy.

The progression from metabolic flexibility to metabolic inflexibility involves maladaptation at multiple biological levels. Mitochondrial dysfunction develops, characterized by reduced oxidative capacity and impaired energy production efficiency. Insulin signaling becomes dysregulated, further impairing nutrient sensing and metabolic switching mechanisms. Chronic low-grade inflammation perpetuates these maladaptations, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of metabolic deterioration.

Key Study Insights

Research published in Cell Reports Medicine emphasizes the interconnected nature of whole body and tissue-specific metabolic flexibility in cardiometabolic health. The findings reveal that maintaining metabolic flexibility isn't merely about switching between fuel sources—it's about the coordinated optimization of metabolic pathways across multiple organs. When this coordination breaks down, the consequences can be significant, contributing to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

The research demonstrates that individuals with high metabolic flexibility display better glucose control, improved blood lipid profiles, and enhanced cardiovascular function compared to those with metabolic inflexibility. This suggests that metabolic flexibility isn't just a biomarker of health—it's a modifiable therapeutic target.

Complementary research in Cell Metabolism establishes metabolic flexibility as a fundamental characteristic of health status, examining how this capacity differs across disease states (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017). The investigation demonstrates that metabolic flexibility in health enables adaptive responses to variable energy availability, while metabolic flexibility in disease becomes severely compromised, even when sufficient energy substrates exist. This distinction proves critical for understanding disease pathophysiology and designing effective interventions.

Metabolic Flexibility and Cardiometabolic Disease Prevention

One of the most compelling reasons to focus on metabolic flexibility is its profound connection to cardiometabolic health. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease continues to rise globally, and many of these conditions share a common underlying problem: metabolic inflexibility (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

When your body loses the ability to efficiently switch between fuel sources, several problematic adaptations occur. Your cells become less responsive to insulin, creating a vicious cycle where elevated blood glucose triggers more insulin production, further impairing metabolic flexibility. This represents a fundamental departure from healthy metabolic function.

Metabolic flexibility acts as a protective mechanism against these conditions through multiple pathways. First, it promotes healthy body composition by enhancing your body's ability to utilize stored fat as fuel. Second, it reduces chronic inflammation, a key driver of cardiovascular disease. Third, it improves endothelial function—the health of blood vessel linings—which is essential for preventing atherosclerosis.

Research in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings emphasizes that metabolic flexibility significantly impacts health outcomes across diverse populations. The investigation found that individuals demonstrating high metabolic flexibility had substantially lower rates of type 2 diabetes, maintained healthier blood pressure levels, and exhibited better lipid profiles (Palmer & Clegg, 2022). Notably, these benefits appeared independent of age or genetics, suggesting that metabolic flexibility is a modifiable factor accessible to virtually everyone.

The mechanisms underlying these protective effects involve both direct metabolic improvements and indirect systemic benefits. By reducing the metabolic burden on your pancreas, metabolic flexibility helps preserve insulin-producing beta cell function. By decreasing visceral fat accumulation, it reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. By improving mitochondrial function, it enhances cellular energy production efficiency.

The Role of Metabolic Flexibility in Energy Homeostasis

Your body's ability to maintain stable energy levels depends critically on metabolic flexibility. When you possess genuine metabolic flexibility, you can seamlessly adapt to dietary changes, exercise variations, and different life circumstances without destabilizing your energy systems (Smith et al., 2018).

Consider what happens during a prolonged fast or during intense endurance exercise. Your body must quickly mobilize fat stores and shift from carbohydrate oxidation to fat oxidation. This isn't a simple switch—it requires coordinated changes across multiple tissues and regulatory systems. Your liver increases ketone production, your muscles shift from glucose to fat and ketone utilization, and your brain gradually adapts to utilizing alternative fuels.

Individuals with robust metabolic flexibility undergo these transitions with minimal discomfort. Those with metabolic inflexibility often experience energy crashes, difficulty concentrating, mood disturbances, and intense cravings—all signals that their metabolic systems are struggling to adapt.

Understanding the Adaptation Process

Research in Endocrine Reviews provides comprehensive insights into metabolic flexibility as an adaptation to energy resources and requirements. The review establishes that metabolic flexibility isn't a fixed trait but rather a dynamic capacity that fluctuates based on lifestyle, diet, exercise patterns, and health status (Smith et al., 2018).

During health, your body continuously adapts its metabolic preferences to match current energy availability and demands. You inherit genetic predispositions toward certain metabolic patterns, but these represent starting points rather than destiny. Through appropriate lifestyle interventions, virtually everyone can meaningfully improve their metabolic flexibility.

The research identifies several critical factors influencing metabolic flexibility: physical activity levels, dietary macronutrient composition, sleep quality, stress management, and age-related changes. Importantly, the review notes that age-associated decline in metabolic flexibility isn't inevitable. Active, metabolically healthy individuals maintain high metabolic flexibility well into advanced age, suggesting that lifestyle factors exert more influence than chronological aging alone.

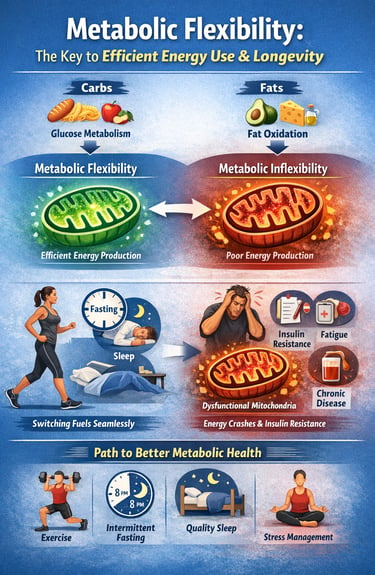

Pathways to Developing Metabolic Flexibility

The exciting news is that metabolic flexibility isn't something you're born with and stuck with forever. Like any physiological capacity, it's trainable and improvable through deliberate practices (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

Exercise and Physical Activity

Regular exercise represents one of the most powerful interventions for enhancing metabolic flexibility. Both endurance exercise and resistance training improve your body's ability to shift between fuel sources. Endurance exercise, particularly when performed at moderate intensities, trains your aerobic system to efficiently utilize fat for fuel. Resistance training preserves and builds muscle tissue, which serves as a metabolic hub for fuel utilization.

Importantly, varied exercise patterns produce superior results compared to monotonous routines. Incorporating different intensities, durations, and modalities keeps your metabolic systems adaptable and responsive.

Dietary Approaches

Your dietary choices profoundly influence metabolic flexibility. While numerous dietary philosophies exist, the underlying principle for optimizing metabolic flexibility involves occasionally challenging your metabolic systems with fuel scarcity (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating create windows where your body must efficiently mobilize and utilize fat stores. This isn't about eating fewer total calories but rather about creating temporal separation between eating and fasting periods. Such patterns activate metabolic switching mechanisms and enhance your body's ability to transition between glucose and fat oxidation.

Simultaneously, maintaining adequate nutrition during eating windows ensures that your metabolic systems have the building blocks necessary for optimal function. This includes sufficient protein for tissue maintenance and adaptation, adequate micronutrients for enzymatic function, and quality fat sources that support hormone production and cellular signaling.

Sleep and Recovery

Often overlooked, sleep quality dramatically influences metabolic flexibility. During sleep, your body undergoes crucial metabolic processes including growth hormone secretion, glymphatic system clearing, and mitochondrial maintenance. Poor sleep impairs these processes and reduces metabolic flexibility, manifesting as increased insulin resistance, elevated fasting glucose, and reduced fat oxidation capacity.

Prioritizing sleep hygiene—consistent sleep schedules, cool sleeping environments, darkness, and minimized evening light exposure—supports optimal metabolic flexibility.

Stress Management

Chronic stress impairs metabolic flexibility through multiple mechanisms. Elevated cortisol promotes preferential carbohydrate utilization, suppresses fat oxidation, and impairs glucose tolerance. Over time, chronic stress-induced metabolic inflexibility contributes to weight gain, metabolic dysfunction, and increased disease risk.

Implementing stress-reduction practices—meditation, breathwork, nature exposure, and social connection—supports metabolic health and enhances metabolic flexibility.

Metabolic Flexibility and Healthy Aging

One of the most intriguing connections emerging from recent research involves the relationship between metabolic flexibility and longevity. Compelling evidence suggests that the ability to efficiently switch between metabolic fuel sources represents a fundamental mechanism of healthy aging (Ang et al., 2025).

As we age, metabolic flexibility naturally declines in sedentary individuals, contributing to age-associated metabolic dysfunction and disease risk. However, active individuals with good metabolic health maintain high metabolic flexibility throughout life. This suggests that deteriorating metabolic flexibility isn't an inevitable consequence of aging but rather a response to reduced physical activity and metabolic underuse.

Research demonstrates that individuals maintaining robust metabolic flexibility experience not only longer lifespans but also dramatically improved healthspan—the portion of life spent in good health. The mechanisms involve multiple pathways: reduced chronic inflammation, improved mitochondrial function, enhanced DNA repair capacity, and optimized hormone signaling.

Metabolic Flexibility in Disease States

The concept of metabolic flexibility gains particular relevance when examining disease states. Many chronic conditions share a common feature: metabolic inflexibility (Shoemaker et al., 2023). Understanding this connection opens new therapeutic possibilities.

Recent research provides critical insights into how metabolic inflexibility develops and perpetuates disease states. The pathology underlying metabolism dysfunction involves a progressive loss of metabolic adaptability, wherein tissues lose their capacity to appropriately respond to changing fuel availability (Shoemaker et al., 2023). This deterioration occurs through several interconnected mechanisms: mitochondrial impairment, dysregulated signaling pathways, chronic inflammation, and maladaptive gene expression.

What distinguishes metabolic inflexibility from simple obesity or metabolic disease is the fundamental inability to switch fuel sources. An individual may possess adequate fat stores but be metabolically unable to mobilize them for energy. This represents a qualitatively different problem than mere caloric excess, requiring distinctly different therapeutic approaches focused on restoring metabolic switching capacity rather than simply reducing calorie intake.

Type 2 Diabetes

Metabolic inflexibility represents a core feature of type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. Individuals with this condition often exhibit severe glucose-dependency—their bodies struggle to efficiently utilize fat for fuel. This metabolic rigidity perpetuates insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.

Research demonstrates that impaired fat oxidation capacity precedes and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017). Individuals with reduced metabolic flexibility display reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and increased lipid accumulation within muscle tissue, creating a metabolic milieu conducive to insulin resistance development.

Interventions that restore metabolic flexibility—such as structured physical training and temporal eating patterns—demonstrate remarkable therapeutic potential, often producing improvements rivaling pharmaceutical interventions.

Cardiovascular Disease

The heart preferentially utilizes fat for fuel in healthy states, with approximately 60% of cardiac ATP production deriving from fat oxidation. Individuals with cardiovascular disease often display impaired cardiac metabolic flexibility, losing the ability to efficiently shift between fuel sources (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

This cardiac metabolic inflexibility contributes to reduced exercise tolerance, diastolic dysfunction, and increased vulnerability to ischemic injury. Restoring cardiac metabolic flexibility represents an emerging therapeutic target, with research suggesting that interventions improving whole-body metabolic flexibility may particularly benefit cardiac function.

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity frequently develops in conjunction with metabolic inflexibility. Rather than obesity causing metabolic inflexibility, evidence increasingly suggests that progressive loss of metabolic flexibility creates the metabolic conditions predisposing to obesity (Shoemaker et al., 2023). Individuals unable to efficiently oxidize fat accumulate excess adipose tissue, creating a vicious cycle where increased fat storage further impairs fat oxidation capacity.

Metabolic syndrome—the cluster of central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and glucose intolerance—represents a manifestation of severe metabolic inflexibility. Interventions targeting metabolic flexibility restoration offer promise for addressing this multifactorial condition.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

The brain's metabolic flexibility also appears relevant to neurodegenerative disease prevention. While the brain typically prefers glucose, it can efficiently utilize ketones derived from fat metabolism. Some research suggests that regular practice with metabolic switching through intermittent fasting or specific dietary patterns may provide neuroprotective benefits by preserving neuronal metabolic flexibility and reducing reliance on glucose, though research in this area remains preliminary.

Common Misconceptions About Metabolic Flexibility

Several myths surround metabolic flexibility, clouding public understanding:

Misconception 1: Metabolic flexibility means you can eat anything without consequences. In reality, metabolic flexibility reflects your physiological capacity to utilize different fuels, not an invitation to ignore nutrition quality. Even metabolically flexible individuals benefit from nutrient-dense food choices.

Misconception 2: You must be thin to have metabolic flexibility. While obesity often impairs metabolic flexibility, individuals across the weight spectrum can work to improve it. Additionally, some individuals with excess weight maintain relatively good metabolic flexibility.

Misconception 3: Metabolic flexibility develops through one intervention alone. Optimal metabolic flexibility requires a multifaceted approach encompassing exercise, nutrition, sleep, and stress management (Smith et al., 2018).

Misconception 4: Your metabolic flexibility is entirely genetic. While genetics influence your baseline metabolic flexibility, lifestyle factors exert substantial influence (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

Misconception 5: Metabolic inflexibility is irreversible. While challenging to reverse in advanced disease states, metabolic inflexibility remains responsive to targeted interventions, particularly when implemented early (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

Practical Implementation Guide

Ready to enhance your metabolic flexibility? Consider implementing these evidence-based strategies:

Start with movement. Incorporate both aerobic exercise at moderate intensities and resistance training. Aim for consistency rather than intensity initially—regular, moderate activity outperforms sporadic intense efforts for building metabolic flexibility (Smith et al., 2018).

Introduce temporal eating patterns. Begin with a modest time-restricted eating window, perhaps 12 hours of eating followed by 12 hours of fasting. Gradually extend the fasting window as your body adapts and your metabolic flexibility improves. This creates regular periods where your body must efficiently mobilize fat stores.

Optimize your sleep. Prioritize seven to nine hours of consistent sleep. Establish regular sleep and wake times, even on weekends. Create a cool, dark sleeping environment and minimize light exposure in the evening.

Manage stress intentionally. Develop a daily stress-management practice, whether meditation, breathwork, journaling, or time in nature.

Assess your nutrition. Ensure adequate protein intake to support tissue maintenance and metabolic adaptation. Include diverse, nutrient-dense foods providing vitamins and minerals necessary for optimal metabolic function (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

Monitor your progress. Track metrics like energy levels, exercise capacity, sleep quality, and body composition changes. These indirect indicators often precede changes in formal metabolic testing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How long does it take to improve metabolic flexibility? A: Most individuals notice improvements within 2-4 weeks with consistent implementation of lifestyle changes. However, substantial adaptations typically require 8-12 weeks. Patience and consistency matter more than intensity.

Q: Can I improve metabolic flexibility without intermittent fasting? A: Absolutely. While intermittent fasting provides one tool, regular exercise, adequate sleep, stress management, and quality nutrition all significantly enhance metabolic flexibility independent of eating patterns (Smith et al., 2018).

Q: Does metabolic flexibility matter if I don't have metabolic disease? A: Yes. Metabolic flexibility directly influences energy levels, cognitive function, mood, resilience to stress, and longevity potential. Everyone benefits from optimizing this capacity (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

Q: Can I test my metabolic flexibility? A: Clinical assessments exist, including indirect calorimetry and specialized metabolic testing, though these remain primarily research tools. More practically, indirect markers like stable energy levels, reduced sugar cravings, and improved exercise performance indicate improving metabolic flexibility.

Q: Is metabolic flexibility the same as having a fast metabolism? A: No. Metabolic flexibility refers to adaptability, not speed. You can have a relatively slow metabolic rate but high metabolic flexibility, or vice versa.

Q: What role does age play in metabolic flexibility? A: While aging is associated with declining metabolic flexibility in sedentary populations, active individuals maintain high metabolic flexibility throughout life (Smith et al., 2018). Age-related decline isn't inevitable.

Q: How does metabolic inflexibility differ from simply being overweight? A: An individual can be overweight yet maintain reasonable metabolic flexibility, or lean yet display metabolic inflexibility. The distinction matters because it determines which interventions will be most effective (Shoemaker et al., 2023).

Q: Can metabolic dysfunction be reversed? A: In most cases, yes. Research demonstrates that targeted interventions addressing metabolic flexibility can substantially reverse metabolic dysfunction and restore normal metabolic switching capacity, even in established disease states (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017).

Key Takeaways

Metabolic flexibility is your body's capacity to efficiently switch between carbohydrate and fat oxidation based on availability and demand (Goodpaster & Sparks, 2017)

Metabolic inflexibility represents a pathological state underlying numerous chronic diseases and involves progressive loss of adaptive capacity (Shoemaker et al., 2023)

This adaptability extends to tissue-specific metabolic flexibility, with different organs optimizing their fuel utilization (Ang et al., 2025)

High metabolic flexibility protects against cardiometabolic diseases, supports healthy weight maintenance, and promotes longevity

Metabolic flexibility is not fixed; it's modifiable through exercise, temporal eating patterns, sleep optimization, and stress management (Smith et al., 2018)

The pathology of metabolic dysfunction involves multiple interconnected mechanisms requiring multifaceted intervention approaches (Shoemaker et al., 2023)

The concept of metabolic flexibility transforms how we understand aging, disease prevention, and optimal health (Palmer & Clegg, 2022)

Individuals maintaining robust metabolic flexibility experience both extended lifespan and improved healthspan

Author’s Note

This article was written to bridge the widening gap between advanced metabolic science and everyday clinical understanding. While terms such as obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes dominate public discourse, they often obscure a more fundamental physiological problem: the progressive loss of metabolic adaptability. Metabolic flexibility—once considered an abstract research concept—has now emerged as a unifying framework that explains why metabolic diseases develop, why they progress, and why they respond so differently to identical interventions.

The perspectives presented here are grounded in peer-reviewed human and mechanistic research from leading metabolic journals. However, this article does not advocate extreme dietary practices, rigid protocols, or one-size-fits-all solutions. Instead, it emphasizes restoring physiological resilience through evidence-based lifestyle strategies that align with human biology.

Clinicians are encouraged to view metabolic inflexibility as an early, modifiable pathological state rather than an inevitable consequence of aging or weight gain. Readers without a medical background should understand that metabolic health is not defined by appearance or calorie counting, but by the body’s ability to efficiently adapt to changing energy demands.

The goal of this work is not merely to inform, but to reframe metabolic health as a dynamic, trainable capacity—one that offers powerful opportunities for disease prevention, improved healthspan, and longevity.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Obesity and Fatty Liver Disease: What Science Says About Risk and Health | DR T S DIDWAL

Intermittent Fasting: Metabolic Health Benefits and the Evidence on Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

Activate Your Brown Fat: A New Pathway to Longevity and Metabolic Health | DR T S DIDWAL

Leptin vs. Adiponectin: How Your Fat Hormones Control Weight and Metabolic Health | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Ang, J. C., Sun, L., Foo, S. R., Leow, M. K., Vidal-Puig, A., Fontana, L., & Dalakoti, M. (2025). Perspectives on whole body and tissue-specific metabolic flexibility and implications in cardiometabolic diseases. Cell Reports Medicine, 6(9), 102354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102354

Goodpaster, B. H., & Sparks, L. M. (2017). Metabolic flexibility in health and disease. Cell Metabolism, 25(5), 1027–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.015

Palmer, B. F., & Clegg, D. J. (2022). Metabolic flexibility and its impact on health outcomes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 97(4), 761–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.012

Shoemaker, M. E., Gillen, Z. M., Fukuda, D. H., & Cramer, J. T. (2023). Metabolic flexibility and inflexibility: Pathology underlying metabolism dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(13), 4453. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134453

Smith, R. L., Soeters, M. R., Wüst, R. C. I., & Houtkooper, R. H. (2018). Metabolic flexibility as an adaptation to energy resources and requirements in health and disease. Endocrine Reviews, 39(4), 489–517. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00211