Menopause and Heart Disease: Why Midlife Is a Cardiometabolic Turning Point

Menopause and heart disease: Learn how estrogen decline, rising uric acid, and vascular dysfunction increase cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women.

AGINGMETABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/19/202612 min read

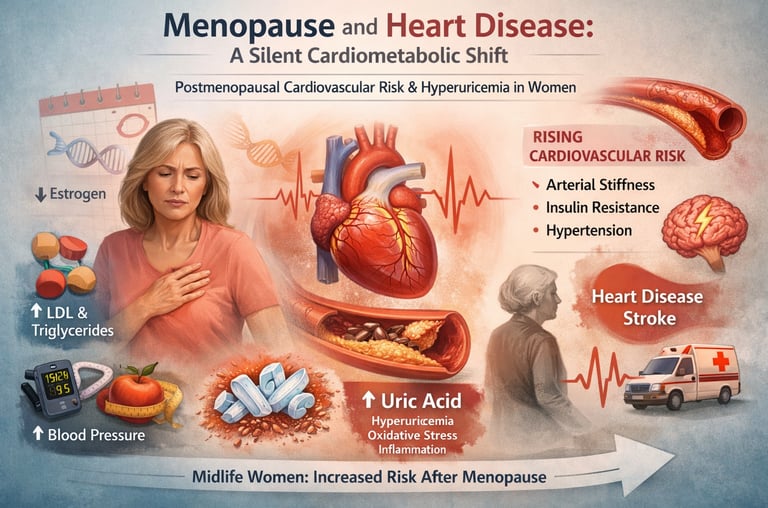

Menopause is often described as a natural phase of aging — the end of reproductive life. But emerging evidence makes one thing clear: menopause and heart disease are deeply interconnected. For many women, the menopausal transition represents a silent turning point in cardiovascular biology. Long before symptoms of coronary artery disease appear, subtle shifts in hormones begin reshaping lipid metabolism, vascular tone, fat distribution, glucose regulation, and inflammatory pathways (Nappi et al., 2022).

The decline in estrogen is not just a reproductive event; it is a cardiometabolic inflecton point. As estrogen levels fall, protective effects on endothelial function, nitric oxide production, and insulin sensitivity diminish. The result is a measurable rise in postmenopausal cardiovascular risk, including increases in LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, visceral adiposity, arterial stiffness, and blood pressure (Guo & Lau, 2025). Women’s lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease accelerates after menopause, eventually equaling or surpassing that of men.

One of the most overlooked contributors to this transition is hyperuricemia in women. Estrogen promotes renal uric acid excretion; its withdrawal leads to rising serum uric acid levels during and after menopause. Elevated uric acid is increasingly recognized as a driver of endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and cardiometabolic disease — extending far beyond gout (Du et al., 2024).

Understanding menopause not as a hormonal footnote but as a systemic metabolic transformation is critical. The intersection of estrogen withdrawal, vascular aging, and rising uric acid may explain why cardiovascular disease becomes the leading cause of death in women — and why midlife is the most important window for prevention.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Window of Opportunity" for Hormones

Scientific Perspective: The Timing Hypothesis suggests that Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) has a favorable benefit-risk ratio when initiated within 10 years of menopause onset or before age 60. Early initiation supports endothelial function and lipid metabolism before permanent atherosclerotic changes occur.

Don’t "wait and see" until symptoms become unbearable. If you are considering hormone therapy for symptom relief or long-term health, the best time to discuss it with your doctor is at the very beginning of the transition, not five years after your periods have stopped.

2. Uric Acid: The "Hidden" Metabolic Marker

Scientific Perspective: Estrogen is uricosuric, meaning it helps the kidneys clear uric acid. As estrogen drops, serum uric acid levels rise, triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and promoting arterial stiffness and insulin resistance.

When you get your annual blood work, a "normal" cholesterol panel doesn't tell the whole story. Ask your doctor to add a Serum Uric Acid test. It is a cheap, simple way to see if your internal "flame" of inflammation is rising during menopause.

3. The "Body Composition" Shift

Scientific Perspective: Menopause triggers a shift from subcutaneous fat to visceral adiposity (fat around the organs). This transition is driven by the loss of 17β-estradiol and is a primary driver of systemic inflammation and "Metabolic Syndrome."

The scale might stay the same, but your clothes might fit differently—this is the "menopausal middle." Focus less on total weight and more on waist circumference and muscle preservation. Strength training becomes a non-negotiable medical intervention at this stage, not just a hobby.

4. Vasomotor Symptoms as a Bio-Indicator

Scientific Perspective: Frequent and severe hot flashes (vasomotor symptoms) are not just "nuisances"; they are linked to autonomic nervous system dysregulation and are independent predictors of subclinical cardiovascular disease and calcium buildup in the arteries.

Think of hot flashes as your body’s "check engine light." If they are frequent and intense, it’s a signal to be extra vigilant about your heart health screenings, blood pressure, and stress management.

5. The Route of Delivery Matters

Scientific Perspective: Transdermal estrogen (patches, gels, or sprays) bypasses the "first-pass" hepatic metabolism. Unlike oral pills, transdermal options do not increase the risk of blood clots (venous thromboembolism) because they don't stimulate the liver to produce clotting factors.

If you are worried about the "clot risk" associated with hormones, ask about patches or gels. They deliver the same relief as a pill but with a much cleaner safety profile for your blood vessels and liver.

6. Atypical Symptom Recognition

Scientific Perspective: Women are more likely to experience microvascular dysfunction rather than major vessel blockages. This leads to "atypical" presentations of cardiac distress, such as extreme fatigue, nausea, or shortness of breath, rather than the classic "elephant on the chest" pain.

You know your body better than anyone. If you feel a sudden, unexplained drop in your exercise tolerance or "weird" indigestion and fatigue that doesn't go away with rest, insist on a cardiac workup. Do not let a provider dismiss these as "just stress" or "just menopause."

Part 1: Menopause as a Cardiometabolic Transition — Not Just a Hormonal Event

The Estrogen Withdrawal Effect

The landmark paper by Nappi et al. (2022) in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology reframes menopause as a systemic metabolic event rather than a purely gynecological one. Estrogen, particularly 17β-estradiol, exerts powerful protective effects on the cardiovascular system: it promotes vasodilation, reduces inflammation, modulates lipid metabolism, and supports insulin sensitivity. When estrogen levels plummet during the menopausal transition, these protective mechanisms are progressively withdrawn.

The downstream consequences are measurable and clinically significant. Women in the menopausal transition experience increases in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides, alongside decreases in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Visceral adiposity increases even in the absence of overall weight gain, as fat redistributes from subcutaneous to intra-abdominal depots — a pattern strongly associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk. Blood pressure tends to rise, arterial stiffness increases, and endothelial function declines (Nappi et al., 2022).

Key Takeaway — Nappi et al. (2022): Menopause is a true cardiometabolic transition, not merely a hormonal one. The withdrawal of estrogen drives clinically meaningful changes in lipid profiles, visceral fat distribution, blood pressure, and vascular function — all of which compound cardiovascular risk in midlife women. Clinicians must evaluate and address these changes as proactively as they would in any high-risk patient population.

Part 2: Closing the Clinical Competency Gap

Why Providers Are Under-Prepared

Despite the clear evidence that menopause accelerates cardiometabolic risk, a striking gap exists between what science knows and what clinicians do. Dastmalchi et al. (2025), writing in JACC Advances, systematically examined the cardiovascular clinical competency framework for the menopausal transition and found it wanting.

Their analysis highlights that many cardiologists, primary care providers, and gynecologists lack structured training in recognizing and managing the cardiometabolic sequelae of menopause. Menopause-specific cardiovascular risk factors — including vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats), premature or early menopause, and surgical menopause — are frequently underweighted in standard cardiovascular risk assessments. Yet vasomotor symptoms, for example, have been independently associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis and adverse cardiovascular events.

Dastmalchi et al. (2025) call for dedicated cardiovascular competencies for clinicians managing midlife women, arguing that a multidisciplinary, sex-informed approach is essential. This includes integrating questions about menopause timing and symptom burden into routine cardiovascular screenings, recognizing sex-specific risk enhancers, and counseling women proactively about lifestyle interventions and, where appropriate, menopausal hormone therapy.

This competency gap has real-world consequences: women presenting with chest pain, dyspnea, or fatigue during perimenopause are more likely to be under-investigated and under-treated compared to men with equivalent symptom burdens. Closing this gap is not merely an academic concern — it is a matter of health equity and clinical quality.

Key Takeaway — Dastmalchi et al. (2025): There is a significant, largely unaddressed gap in cardiovascular clinical competency around the menopausal transition. Cardiometabolic risk factors specific to midlife women — including vasomotor symptoms, menopause timing, and hormonal changes — are routinely underweighted in standard risk assessment frameworks, contributing to disparities in diagnosis and treatment.

Part 3: Hormones, the Heart, and the Evidence on Menopausal Hormone Therapy

Navigating the Hormone Therapy Debate

Few topics in women's health have generated more confusion — and more clinical paralysis — than menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). The publication of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trials in the early 2000s sent a chill through prescribing practices worldwide. But as Guo and Lau (2025) document in Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, the science has evolved considerably since then, and a nuanced, individualized approach to MHT is now supported by the weight of contemporary evidence.

Guo and Lau (2025) review the cardiovascular implications of hormonal changes during menopause and evaluate the evidence for MHT in reducing cardiometabolic risk. Their analysis underscores several critical points. First, the timing of MHT initiation matters enormously — the so-called "timing hypothesis" or "window of opportunity" suggests that MHT initiated within ten years of menopause or before age 60 may carry cardiovascular benefits, while initiation in older, more established postmenopausal women carries higher risk. Second, the type, dose, and route of administration of hormones influence the risk-benefit profile: transdermal estrogen, for example, avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism and is associated with a more favorable thrombotic profile compared to oral formulations.

Beyond MHT, Guo and Lau (2025) emphasize the importance of lifestyle modification — aerobic exercise, dietary pattern, smoking cessation, and weight management — as the foundation of cardiovascular risk reduction in midlife women. They also highlight emerging pharmacological strategies, including SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists, that may offer cardiometabolic benefits relevant to this population.

The broader message is one of individualization: a 52-year-old woman with bothersome hot flashes, no contraindications, and recent menopause onset has a very different risk-benefit calculus than a 67-year-old woman with established coronary artery disease. One-size-fits-all approaches serve neither group well.

Key Takeaway — Guo & Lau (2025): The cardiovascular implications of menopause and hormone therapy are nuanced and highly time-dependent. When initiated early in the menopausal transition, MHT may confer cardiovascular benefits; however, individualization based on timing, formulation, and patient-specific risk factors is essential. Lifestyle modification remains the cornerstone of cardiometabolic risk reduction in midlife women.

Part 4: The Underappreciated Role of Uric Acid

Hyperuricemia — A Metabolic Canary in the Coal Mine

While lipids and blood pressure dominate cardiovascular risk conversations, a growing body of evidence positions serum uric acid as an important and often overlooked biomarker of cardiometabolic dysfunction. Du et al. (2024), in a comprehensive review published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, provide a landmark synthesis of the mechanisms by which elevated uric acid — hyperuricemia — contributes to a wide spectrum of diseases, and the therapeutic advances targeting this pathway.

The Menopause-Uric Acid Connection

Here lies a crucial and often unrecognized link: estrogen is uricosuric, meaning it promotes renal excretion of uric acid. Premenopausal women generally have lower serum uric acid levels than age-matched men — a gap attributable in substantial part to estrogen's renal effects. When estrogen levels fall during menopause, this uricosuric protection is lost, and serum uric acid rises. Postmenopausal women, as a result, approach the elevated uric acid levels typically seen in men — and with it, their associated cardiometabolic risks.

This means that hyperuricemia in midlife women is not coincidental. It is a predictable metabolic consequence of estrogen withdrawal, mechanistically connected to the same cardiometabolic pathways described by Nappi et al. (2022) and Guo and Lau (2025). Yet uric acid measurement remains absent from most standard menopausal workups and cardiovascular risk assessments in women.

Du et al. (2024) also review therapeutic advances in hyperuricemia management, including xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and febuxostat), uricosuric agents (benzbromarone, lesinurad), and novel biologics and small molecules targeting uric acid transport and the inflammatory cascade. They emphasize that treatment should be guided not only by gout prevention but by the broader cardiometabolic risk profile of the individual patient.

Key Takeaway — Du et al. (2024): Hyperuricemia is a multifaceted cardiometabolic risk factor linked through inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction to cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and beyond. The loss of estrogen's uricosuric effect at menopause creates a predictable rise in uric acid in postmenopausal women — an underappreciated but clinically important dimension of the menopausal cardiometabolic transition.

Part 5: Building an Integrated Framework for Midlife Women's Cardiometabolic Health

Menopause and Heart Disease: The Hidden Cardiometabolic Shift Every Clinician Must Address

1️⃣ Menopause Is a Cardiometabolic Event — Not Just a Reproductive Milestone

Menopause and heart disease are biologically interconnected through estrogen withdrawal.

Estrogen regulates nitric oxide production, endothelial function, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity.

Its decline accelerates arterial stiffness, central adiposity, dyslipidemia, and vascular inflammation.

Cardiovascular disease becomes the leading cause of death in women after menopause, not cancer.

2️⃣ Postmenopausal Cardiovascular Risk Is Underestimated

Traditional risk calculators underrepresent postmenopausal cardiovascular risk.

Vasomotor symptoms, early menopause, and surgical menopause are independent risk enhancers.

Women often present with atypical symptoms (fatigue, dyspnea, nausea), leading to underdiagnosis.

Risk acceleration occurs silently over 5–10 years following the menopausal transition.

3️⃣ Lipid and Metabolic Remodeling After Estrogen Withdrawal

↑ LDL cholesterol

↑ Triglycerides

↓ HDL functional quality

↑ Visceral adiposity (even without major weight gain)

↑ Insulin resistance

This metabolic clustering resembles early metabolic syndrome and directly amplifies atherosclerotic progression.

4️⃣ Hyperuricemia in Women: The Overlooked Risk Multiplier

Estrogen has a uricosuric effect — its decline raises serum uric acid.

Hyperuricemia in women increases during perimenopause and persists postmenopause.

Elevated uric acid contributes to:

Endothelial dysfunction

Oxidative stress

NLRP3 inflammasome activation

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease

Uric acid should be viewed not merely as a gout marker, but as a cardiometabolic biomarker.

5️⃣ Menopausal Hormone Therapy: Timing Matters

Early initiation (<60 years or within 10 years of menopause) may confer cardiovascular neutrality or benefit in selected women.

Route and formulation influence thrombotic risk (transdermal is often preferred).

Therapy must be individualized — not reflexively avoided or universally prescribed.

6️⃣ Lifestyle Remains Foundational

Resistance and aerobic training improve endothelial function and insulin sensitivity.

Mediterranean-style nutrition reduces inflammation and uric acid burden.

Weight optimization reduces both cardiometabolic and hyperuricemic risk.

7️⃣ A Call for Sex-Informed Cardiometabolic Screening

Elite prevention requires:

Lipid panel

HbA1c and fasting glucose

Blood pressure monitoring

Body composition assessment

Serum uric acid measurement

🔎 Editorial Conclusion

Menopause represents a metabolic inflection point — a window where prevention is not optional but imperative. Recognizing the convergence of estrogen withdrawal, rising uric acid, and vascular aging allows clinicians to transform midlife from a risk escalation phase into a strategic prevention opportunity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Does menopause directly cause heart disease? Menopause does not directly cause heart disease, but it creates a cluster of cardiometabolic changes — including dyslipidemia, visceral fat gain, insulin resistance, and vascular dysfunction — that significantly increase cardiovascular risk over time. Women's lifetime cardiovascular risk converges with men's after menopause, making this transition a critical window for prevention (Nappi et al., 2022).

2. What is hyperuricemia and why does it matter for menopausal women? Hyperuricemia is the condition of elevated uric acid in the blood. It is linked to gout, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, kidney disease, and metabolic syndrome. During menopause, the loss of estrogen's uricosuric (uric acid-excreting) effect causes uric acid levels to rise in women, increasing their risk of these conditions (Du et al., 2024).

3. Is menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) safe for the heart? The safety of MHT is highly dependent on timing, formulation, and individual patient factors. When initiated early in the menopausal transition (within 10 years of menopause or before age 60) in otherwise healthy women, contemporary evidence suggests a neutral or even favorable cardiovascular profile. Initiating MHT later or in women with established cardiovascular disease carries higher risk (Guo & Lau, 2025).

4. Why are women's cardiovascular symptoms often missed or dismissed? Women tend to present with atypical symptoms of heart disease — fatigue, nausea, shortness of breath rather than classic chest pain — and many risk assessment tools were validated primarily in male populations. Additionally, clinicians often lack specific training in recognizing the cardiometabolic implications of menopause, contributing to under-diagnosis and under-treatment (Dastmalchi et al., 2025).

5. What lifestyle changes most effectively reduce cardiometabolic risk at menopause? The most evidence-supported lifestyle strategies include regular aerobic and resistance exercise, a dietary pattern rich in vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and healthy fats (such as the Mediterranean diet), maintaining a healthy body weight, limiting alcohol, and avoiding smoking. These interventions address multiple cardiometabolic risk factors simultaneously, including lipid levels, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity, and uric acid (Guo & Lau, 2025; Nappi et al., 2022).

6. How can uric acid levels be managed without medication? Dietary modifications can meaningfully reduce uric acid levels. These include limiting high-purine foods (organ meats, shellfish, red meat), reducing fructose and sugary beverage intake, moderating alcohol (especially beer), staying well-hydrated, and consuming more low-fat dairy, which has been shown to have uricosuric effects. Weight loss also lowers uric acid levels. For individuals with persistent hyperuricemia and associated disease burden, pharmacological therapy may be indicated (Du et al., 2024).

7. Should all menopausal women have their uric acid levels checked? While universal screening is not yet a standard guideline recommendation, growing evidence supports measuring uric acid in midlife women as part of a comprehensive cardiometabolic risk assessment, particularly in those with hypertension, metabolic syndrome, kidney disease, or a personal or family history of gout or cardiovascular disease. Clinicians should discuss the relevance of uric acid testing with patients during the menopausal transition.

Author’s Note

Menopause represents one of the most biologically transformative phases in a woman’s life — yet its cardiometabolic implications remain under-recognized in both clinical practice and public discourse. This article was written to bridge that gap.

As an internal medicine physician committed to evidence-based care, my goal is to move the conversation beyond symptom management and toward risk recognition, early prevention, and metabolic precision. The decline in estrogen is not merely a reproductive milestone; it is a systemic shift affecting vascular biology, lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, inflammatory pathways, and uric acid regulation. Understanding this interconnected physiology is essential if we are to reduce the disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women.

The discussion of hyperuricemia in women is intentional. While traditionally associated with gout, uric acid is increasingly recognized as a cardiometabolic biomarker with mechanistic relevance to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and vascular inflammation. Its rise during menopause deserves greater clinical attention.

This article does not advocate for one-size-fits-all treatment. Rather, it supports individualized, sex-informed risk assessment — integrating lifestyle, metabolic screening, and when appropriate, carefully timed menopausal hormone therapy.

Menopause should not be viewed as the beginning of decline, but as a critical window for prevention. With proactive screening, multidisciplinary collaboration, and informed patient engagement, midlife can become a powerful inflection point for long-term cardiovascular health.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Related Articles

Metabolic Plasticity: Epigenetic Adaptations to Calorie Restriction | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Dastmalchi, L. N., Gulati, M., Thurston, R. C., Lau, E., Sarma, A., Marfori, C. Q., Gaffey, A. E., Faubion, S., Laddu, D., Shufelt, C. L., & Sharma, G. (2025). Improving cardiovascular clinical competencies for the menopausal transition: A focus on cardiometabolic health in midlife. JACC Advances, 4(6 Pt 2), 101791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacadv.2025.101791

Du, L., Zong, Y., Li, H., Wang, Q., Xie, L., Yang, B., Pang, Y., Zhang, C., Zhong, Z., & Gao, J. (2024). Hyperuricemia and its related diseases: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(1), Article 212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01916-y

Guo, R., & Lau, E. S. (2025). Matters of the heart: Menopause, hormones, and cardiovascular disease. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine, 27, 74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-025-01131-0

Nappi, R. E., Chedraui, P., Lambrinoudaki, I., & Simoncini, T. (2022). Menopause: A cardiometabolic transition. The Lancet: Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(6), 442–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00076-6