Losing Weight but Weak? Hidden Sarcopenic Obesity Risks Explained

Discover why fat loss may hide muscle loss. Learn 2026 sarcopenic obesity criteria and safe strategies to protect your strength and metabolism

OBESITYSARCOPENIA

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/22/202615 min read

Sarcopenic Obesity: The Hidden Double Burden Reshaping Modern Healthcare

Sarcopenic obesity is not just another aging-related diagnosis — it is a silent biological collision that is redefining risk in modern medicine. Around the world, populations are aging while obesity rates continue to climb. But beneath the surface of rising body weight lies a more insidious shift in body composition: fat mass increases while skeletal muscle mass quietly erodes. This dual process creates a metabolically volatile state known as sarcopenic obesity, where excess adiposity and progressive muscle loss amplify one another in a destructive physiological loop (Axelrod et al., 2023).

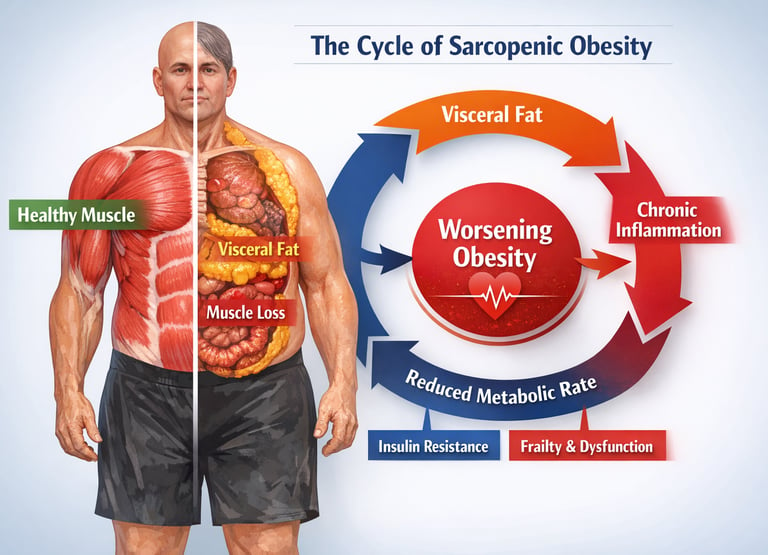

What makes this condition particularly dangerous is not simply the coexistence of two disorders, but their synergy. Visceral adiposity drives chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity, all of which impair muscle protein synthesis and accelerate proteolysis (Axelrod et al., 2023). Meanwhile, declining muscle mass reduces glucose disposal, lowers resting metabolic rate, and worsens metabolic instability. The result is a self-perpetuating cycle of metabolic dysfunction, frailty, and rising cardiometabolic risk.

Recent consensus efforts have confirmed that sarcopenic obesity is not a niche diagnosis but a growing public health concern requiring standardized criteria adapted to regional populations (Chen et al., 2025). Even more concerning, emerging evidence warns that conventional weight-loss strategies — particularly in older adults — may unintentionally worsen muscle loss if not carefully structured around resistance exercise and adequate protein intake (Batsis et al., 2026).

In other words, the crisis is not just obesity. It is the erosion of muscle in the presence of fat — a hidden double burden that demands a fundamentally new clinical paradigm.

Clinical pearls for managing sarcopenic obesity.

1. The "Scale Weight" Mirage

Scientific Perspective: Absolute weight loss is a poor proxy for health in older adults. Total weight reduction without resistance training typically results in a 25–30% loss of lean body mass, which can permanently lower the basal metabolic rate ($BMR$) and increase the risk of "weight-loss-induced sarcopenia."

"Don’t focus solely on the number on the scale. If you lose 10 pounds but 3 of those pounds are muscle, you’ve actually made your body 'weaker' and your metabolism slower. Our goal is to lose the fat while keeping the muscle you already have."

2. The Leucine "Anabolic Threshold"

Scientific Perspective: Older muscles exhibit anabolic resistance, requiring a higher concentration of the amino acid Leucine (approx. 2.5–3g per meal) to trigger the $mTORC1$ pathway. Without reaching this "leucine trigger," protein is simply burned for energy rather than used for muscle repair.

Think of protein like a light switch for your muscles. If you only eat a little bit of protein, the switch doesn't flip 'on.' You need a solid 'dose' of high-quality protein (like Greek yogurt, whey, or lean meat) at every meal to tell your body to start building muscle."

3. Chronic Inflammation as "Muscle Rust"

Scientific Perspective: Visceral adipose tissue functions as an endocrine organ, secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α. These markers don't just cause heart disease; they directly infiltrate muscle fibers, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and "lipotoxicity."

Carrying extra weight around the midsection isn't just 'stored energy.' That fat acts like a chemical factory that sends out 'rust' (inflammation) into your muscles. This rust makes it harder for your muscles to produce the energy you need to stay active."

4. The GLP-1 "Muscle Tax"

Scientific Perspective: While GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., Semaglutide) are revolutionary for weight loss, the rapid caloric deficit they induce can lead to disproportionate skeletal muscle loss in the elderly. This makes concurrent resistance training a non-negotiable clinical requirement, not an "add-on."

"New weight-loss medications are powerful tools, but they come with a 'muscle tax.' If you take them without doing strength exercises, your body might 'eat' its own muscle for energy. We have to pair the medicine with weightlifting to make sure you're losing the right kind of weight."

5. Function Over Appearance (The Sit-to-Stand Test)

Scientific Perspective: In sarcopenic obesity, muscle quality (strength per unit of mass) is often more predictive of mortality than muscle quantity. The 5-Times Sit-to-Stand test is a validated clinical marker of lower-extremity power and a proxy for "functional reserve."

We aren't training for a bodybuilding show; we’re training for independence. Being able to get out of a chair easily or carry your own groceries is the best sign that our plan is working. Your strength is your best insurance policy against falls and hospital stays."

Defining the Problem: Why Consensus Has Been So Difficult to Reach

One of the most persistent challenges in sarcopenic obesity research has been the lack of universally agreed-upon diagnostic criteria. Without consistent definitions, studies are difficult to compare, prevalence estimates vary wildly, and clinical guidelines remain fragmented.

A major step forward came in 2025 with the publication of the Asia-Oceania consensus on sarcopenic obesity (Chen et al., 2025). This landmark consensus statement, developed by experts representing countries across Asia and Oceania — including Japan, India, Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Australia — established formal definitions and diagnostic thresholds appropriate for these populations.

The consensus defines sarcopenic obesity as the simultaneous presence of sarcopenia (assessed through low muscle mass plus either low muscle strength or low physical performance) and obesity (assessed through body mass index, waist circumference, or adiposity measures adjusted for regional cut-offs). Critically, the Asia-Oceania group recognized that body composition thresholds validated in Western populations are not universally applicable. Asian populations tend to carry more adipose tissue at lower BMI values and may develop sarcopenic obesity at different anthropometric thresholds than European or North American counterparts.

Sarcopenic obesity cannot be diagnosed with a one-size-fits-all framework. The Asia-Oceania consensus fills a critical gap by providing regionally appropriate diagnostic criteria, acknowledging that ethnic differences in body composition substantially affect the prevalence and clinical presentation of the condition.

This call for region-specific diagnostic rigor echoes a broader demand in the field. Without precise measurement, clinicians risk misclassifying patients — either missing those who have sarcopenic obesity or over-diagnosing those with normal age-related body composition changes. The consensus from Chen and colleagues represents the kind of methodological harmonization the field has long needed.

What Is Happening Inside the Body? Emerging Biological Mechanisms

Understanding why sarcopenic obesity develops requires looking at several intersecting biological pathways. A comprehensive 2023 review by Axelrod, Dantas, and Kirwan in the journal Metabolism provided one of the clearest mechanistic accounts of this condition to date.

Axelrod et al. (2023) identify a destructive feedback loop at the intersection of inflammation, hormonal dysregulation, and metabolic dysfunction. Excess adipose tissue — particularly visceral and intramuscular fat — releases pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These inflammatory mediators directly impair muscle protein synthesis while promoting muscle protein breakdown, a process known as proteolysis. Simultaneously, increased adiposity is associated with insulin resistance, which further undermines the anabolic signaling pathways that maintain muscle mass.

The authors also highlight the role of lipotoxicity — the accumulation of lipid intermediates within muscle cells — which disrupts mitochondrial function and impairs the muscle's ability to generate energy efficiently. This creates a vicious cycle: less functional muscle leads to reduced physical activity, which leads to further fat accumulation, which leads to more inflammation and muscle loss.

Hormonal changes, particularly the age-related decline in testosterone, estrogen, and growth hormone, compound these problems. These anabolic hormones are critical for preserving muscle mass, and their decline with aging removes a key protective buffer against sarcopenic obesity.

Sarcopenic obesity is driven by a self-reinforcing cycle of inflammation, lipotoxicity, hormonal decline, and insulin resistance. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing therapies that target the root cause, not merely the symptoms, of the condition.

The mechanisms described by Axelrod and colleagues have important implications for treatment: interventions that address only fat loss without protecting muscle, or that build muscle without reducing metabolic inflammation, are unlikely to produce lasting benefit.

The Research Landscape: Mapping Two Decades of Progress

To understand where the field is heading, it helps to understand where it has been. A 2025 bibliometric analysis by Zhang et al.(2025). published in Frontiers in Nutrition mapped the global research landscape of nutrition and exercise for sarcopenic obesity, analyzing publication trends, key themes, and institutional collaborations across the scientific literature.

Their analysis reveals a steep and accelerating growth curve in sarcopenic obesity research, with the volume of relevant publications roughly doubling between 2015 and 2024. China, the United States, South Korea, and Italy emerged as the most prolific contributing nations. The most frequently studied interventions clustered around three major themes: resistance exercise training, protein supplementation (particularly leucine-enriched protein and essential amino acid blends), and combined nutrition-exercise programs.

Zhang et al. also identified emerging research frontiers — areas where evidence is growing but where much remains to be established. These include the role of gut microbiota in body composition, the potential of specific dietary patterns (such as the Mediterranean diet) in preventing sarcopenic obesity, and the interaction between sleep quality, circadian biology, and muscle-fat dynamics.

The bibliometric analysis highlights an important structural gap: while nutritional and exercise interventions dominate the published literature, studies specifically tailored to the concurrent management of both muscle loss and excess fat — rather than treating each condition sequentially — remain underrepresented. Most trials still tend to optimize for one outcome at the expense of the other.

Research into nutrition and exercise for sarcopenic obesity is growing rapidly, but the field remains siloed. Future progress requires integrated trials that simultaneously optimize muscle anabolism and fat catabolism, informed by emerging data on the microbiome, chronobiology, and personalized nutrition.

Diagnosis and Treatment in Clinical Practice

For the practicing clinician, sarcopenic obesity presents a genuine dilemma. Standard clinical tools — BMI, waist circumference, DEXA scans — each capture part of the picture but none captures it whole. A 2025 clinical review by Habboub, Speer, Gosch, and Singler, published in Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, offered German-speaking clinicians (and the broader international community via translation) a practical guide to the diagnosis and treatment of both sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity.

Habboub et al. (2025) recommend a stepwise diagnostic approach. Screening begins with functional assessments — grip strength measurement and the five-times sit-to-stand test — which are accessible in virtually any clinical setting. Patients who screen positive then undergo body composition analysis, preferably via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) or, where available, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). The combination of low appendicular lean mass with elevated fat mass (adjusted for height or BMI) confirms the diagnosis.

On the treatment side, Habboub and colleagues emphasize that no single pharmacological agent has achieved regulatory approval specifically for sarcopenic obesity. The therapeutic backbone remains structured resistance exercise combined with adequate protein intake. They recommend resistance training at least two to three times weekly, targeting all major muscle groups, alongside a daily protein intake of at least 1.2 to 1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight, ideally distributed evenly across meals to maximize muscle protein synthesis throughout the day.

The review also discusses the potential role of emerging pharmacological options — including GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide), which are increasingly used for weight management — with the important caveat that these agents, while effective for fat loss, carry significant risk of also reducing lean muscle mass, particularly in older adults.

Despite growing clinical awareness, no disease-modifying pharmacotherapy exists specifically for sarcopenic obesity. The most evidence-supported approach remains an integrated program of resistance training and protein-optimized nutrition, delivered consistently and tailored to individual functional capacity.

The Hidden Danger: Weight Loss That Hurts More Than It Helps

Perhaps the most sobering contribution to the recent literature comes from a 2026 perspective piece published in Nature Medicine by Batsis, Donini, and Prado — a trio of internationally recognized experts in geriatric medicine, clinical nutrition, and body composition science.

Batsis et al. (2026) address a paradox that has received insufficient clinical attention: the very interventions most commonly prescribed to manage obesity in older adults — caloric restriction and weight-loss programs — can inadvertently accelerate sarcopenia if not carefully designed. This is because standard caloric restriction, without adequate protein supplementation and resistance exercise, leads to the loss of both fat mass and lean mass. In older adults, whose capacity for muscle protein synthesis is already diminished, this lean mass loss can be disproportionate and difficult to recover.

The authors introduce the concept of "unintended risks" — a spectrum of adverse outcomes that can arise when weight-loss interventions designed primarily for younger, metabolically healthy individuals are applied wholesale to older people with sarcopenic obesity. These risks include accelerated functional decline, increased fall risk, nutritional deficiencies, and paradoxical worsening of metabolic health despite apparent weight loss.

Batsis and colleagues argue compellingly for a fundamental reorientation of clinical goals in this population. Rather than prioritizing weight loss measured in kilograms, clinicians should prioritize functional outcomes: maintaining or improving muscle strength, preserving bone density, enhancing mobility, and optimizing metabolic markers. Fat loss should be a secondary or simultaneous target, not the primary endpoint.

The authors call for randomized controlled trials specifically designed for older adults with sarcopenic obesity — populations that have historically been excluded from major weight-loss trials due to age cutoffs or frailty criteria. Without such evidence, clinicians are making high-stakes decisions based on extrapolated data from younger, healthier populations.

Conventional weight-loss strategies can be actively harmful in older adults with sarcopenic obesity. Interventions must be specifically designed and validated for this population, prioritizing functional preservation over body weight reduction, and incorporating adequate protein and resistance exercise to protect against lean mass loss.

Integrated Treatment: Nutrition and Exercise Working Together

The accumulated evidence from these studies converges on a clear principle: sarcopenic obesity demands integrated, simultaneous intervention — not sequential treatment of obesity followed by muscle-building, or vice versa. The biological mechanisms that link fat accumulation to muscle loss mean that addressing one without the other is likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive.

Resistance Exercise Training

Resistance exercise remains the most potent stimulus for preserving and rebuilding skeletal muscle mass at any age. Studies consistently show that progressive resistance training — using free weights, machines, or resistance bands, with progressively increasing load — can attenuate or partially reverse sarcopenic changes even in older adults. When combined with caloric restriction for fat loss, resistance training protects against the lean mass losses that caloric restriction alone typically induces.

For individuals with sarcopenic obesity, exercise programming should include at minimum two to three resistance sessions per week, supplemented by moderate-intensity aerobic exercise to support cardiometabolic health. Exercise intensity must be calibrated to the individual's functional capacity, with particular attention to fall risk and joint health in frail older patients.

Protein and Nutritional Strategy

Protein is the nutritional pillar of sarcopenic obesity management. Current evidence supports a daily intake of 1.2 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight (or per kilogram of ideal body weight in individuals with severe obesity) for older adults with sarcopenic obesity. Leucine — an essential amino acid that directly activates the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway responsible for muscle protein synthesis — deserves particular attention, and leucine-enriched protein supplements (such as whey protein) are among the most evidence-supported nutritional interventions.

Meal timing also matters: distributing protein intake evenly across three to four meals, rather than concentrating it at dinner (as many Western dietary patterns do), substantially enhances net 24-hour muscle protein synthesis.

Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns — including the Mediterranean diet, rich in omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols, and fiber — may address the chronic low-grade inflammation that underpins sarcopenic obesity. While direct evidence in sarcopenic obesity populations remains limited, the mechanistic rationale and observational data are promising.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What exactly is sarcopenic obesity, and how is it different from regular obesity? Sarcopenic obesity is the simultaneous presence of excess body fat and clinically significant muscle loss (sarcopenia). While regular obesity involves excess fat without necessarily involving muscle deterioration, sarcopenic obesity combines the metabolic risks of both conditions. The combination creates a uniquely dangerous clinical profile because muscle plays a critical role in glucose metabolism and functional mobility — so losing muscle while gaining fat has compounding harmful effects.

2. Who is most at risk of developing sarcopenic obesity? Older adults (typically over 60) are at the highest risk, as aging naturally reduces muscle mass and increases fat accumulation. However, sarcopenic obesity can also develop earlier in people who are physically inactive, consume inadequate protein, experience prolonged illness or hospitalization, or have hormonal conditions that affect body composition. Postmenopausal women and individuals with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome face elevated risk.

3. How is sarcopenic obesity diagnosed? Diagnosis typically requires assessing two components: body composition (to confirm excess fat mass) and muscle health (to confirm low muscle mass and/or low muscle strength or physical performance). Tools used include DEXA scans, bioelectrical impedance analysis, handgrip dynamometry, and functional tests like the five-times sit-to-stand or gait speed assessment. Diagnostic cut-offs vary by region, as highlighted by the Asia-Oceania consensus (Chen et al., 2025).

4. Can sarcopenic obesity be reversed? The condition can be substantially improved with consistent, integrated intervention. Progressive resistance training combined with adequate protein intake has the strongest evidence for rebuilding muscle while supporting fat loss. However, full reversal — particularly of the muscle loss component — becomes progressively harder with advancing age, underscoring the importance of early identification and intervention.

5. Is weight loss always beneficial for people with sarcopenic obesity? Not necessarily, particularly in older adults. As Batsis et al. (2026) warn, conventional caloric restriction can lead to significant lean muscle loss alongside fat loss in this population, potentially worsening functional outcomes. Weight-loss interventions for older adults with sarcopenic obesity must be carefully designed to protect muscle — through adequate protein intake and concurrent resistance exercise — rather than simply reducing body weight.

6. What role do medications like GLP-1 agonists (e.g., semaglutide, tirzepatide) play in sarcopenic obesity? GLP-1 receptor agonists are highly effective at inducing fat loss but carry the significant risk of also reducing lean muscle mass, which is particularly concerning in people with sarcopenic obesity. At present, no pharmacological agent is specifically approved for sarcopenic obesity. If GLP-1 agonists are used in this population, they should always be combined with resistance exercise and high-protein nutrition to mitigate lean mass loss — an area of active clinical research.

7. Are diagnostic thresholds for sarcopenic obesity the same worldwide? No. As demonstrated by the Asia-Oceania consensus (Chen et al., 2025), diagnostic cut-offs for both obesity and sarcopenia need to be adapted for different ethnic populations. Asian populations, for example, tend to develop metabolically significant adiposity at lower BMI values than European populations. Using Western-derived thresholds universally leads to underdiagnosis in some populations and overdiagnosis in others.

Sarcopenic Obesity: Key Points

Definition and Emerging Significance

Sarcopenic obesity is the simultaneous presence of excess adiposity and progressive skeletal muscle loss.

Unlike simple obesity or age-related sarcopenia alone, this condition represents a metabolically volatile state, amplifying cardiometabolic and frailty risks.

Globally, as populations age and obesity rates rise, sarcopenic obesity is becoming a critical public health concern rather than a niche clinical curiosity (Chen et al., 2025).

Mechanistic Insights: The Synergy of Fat and Muscle Loss

Visceral adiposity drives chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and lipotoxicity.

These metabolic insults impair muscle protein synthesis while accelerating proteolysis.

Muscle decline further reduces glucose disposal, lowers resting metabolic rate, and worsens metabolic instability.

The result is a self-perpetuating cycle: fat drives muscle loss, and muscle loss exacerbates fat accumulation (Axelrod et al., 2023).

Clinical and Metabolic Consequences

Increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dyslipidemia.

Heightened susceptibility to frailty, falls, and functional impairment in older adults.

Worsened outcomes during weight-loss interventions, especially if strategies do not preserve lean mass.

Diagnostic Challenges and Public Health Considerations

Traditional BMI-centric assessments underestimate risk, as patients may appear “overweight” without obvious muscle loss.

Consensus guidelines recommend regionalized body composition criteria using DXA, CT, or bioimpedance measurements to accurately identify sarcopenic obesity (Chen et al., 2025).

Early identification is crucial for designing interventions that simultaneously target fat reduction and muscle preservation.

Implications for Lifestyle and Therapeutic Interventions

Resistance training is pivotal to stimulate muscle hypertrophy and preserve metabolic function.

Adequate protein intake, timed appropriately throughout the day, supports muscle protein synthesis and mitigates loss during caloric restriction.

Exercise programs should integrate strength, balance, and mobility training to reduce frailty risk while improving metabolic health.

Conventional caloric restriction without muscle-focused strategies can worsen sarcopenic obesity, highlighting the need for personalized, multimodal approaches (Batsis et al., 2026).

Future Directions and Research Imperatives

Investigating pharmacologic agents that selectively preserve muscle mass while reducing adiposity.

Longitudinal studies to understand muscle-fat interaction across lifespan and its impact on metabolic disease risk.

Public health strategies should emphasize body composition over body weight alone, promoting interventions that sustain lean mass throughout aging.

Conclusion: Redefining Risk in Aging and Obesity

Sarcopenic obesity is not just a combination of two disorders, but a synergistic state with unique risks and treatment challenges.

Clinicians and health policymakers must adopt a paradigm shift: weight loss is insufficient without concurrent muscle preservation.

Awareness, early detection, and integrated intervention strategies can mitigate its devastating metabolic and functional consequences.

Author’s Note:

Sarcopenic obesity represents a silent but growing threat in modern medicine, where rising fat mass coincides with the insidious loss of skeletal muscle. This dual burden amplifies metabolic dysfunction, frailty, and cardiometabolic risk beyond what obesity or muscle loss alone would cause. My goal in this article is to highlight the biological synergy driving this condition, the public health implications, and the importance of interventions that preserve muscle while managing adiposity. Clinicians, researchers, and health-conscious individuals alike should recognize that the traditional focus on weight alone is insufficient — muscle preservation is equally critical for healthy aging and metabolic stability.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

How to Prevent and Reverse Muscle Wasting in Chronic Disease (2025 Guide) | DR T S DIDWAL

Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia: The Critical Connection | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Prevent Sarcopenia: Fight Age-Related Muscle Loss and Stay Strong | DR T S DIDWAL

Who Gets Sarcopenia? Key Risk Factors & High-Risk Groups Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Exercises for Sarcopenia: Strength Training Guide for Older Adults | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Axelrod, C. L., Dantas, W. S., & Kirwan, J. P. (2023). Sarcopenic obesity: Emerging mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Metabolism, 146, 155639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155639

Batsis, J. A., Donini, L. M., & Prado, C. M. (2026). Unintended risks of sarcopenic obesity during weight-loss interventions in older people. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-026-04210-2

Chen, T. P., Kao, H. H., Ogawa, W., Arai, H., Tahapary, D. L., Assantachai, P., Tham, K. W., Chan, D. C., Yuen, M. M., Appannah, G., Fojas, M., Gill, T., Lee, M. C., Saboo, B., Lin, C. C., Kim, K. K., & Lin, W. Y. (2025). The Asia-Oceania consensus: Definitions and diagnostic criteria for sarcopenic obesity. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 19(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2025.05.001

Habboub, B., Speer, R., Gosch, M., & Singler, K. (2025). The diagnosis and treatment of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 122(10), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2024.0248

Zhang, G., Hu, J., Chen, C., Zhu, W., Chen, Y., Cheng, Y., Hu, W., & Rao, Z. (2025). Research trends in nutrition and exercise for sarcopenic obesity: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 12, 1615101. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1615101