How to Reverse Brain Aging: The Science Behind Fitness, Brain Age, and Dementia Risk

Discover how exercise lowers brain age, improves memory, and reduces dementia risk. Explore the latest research on fitness and cognitive decline.

AGINGEXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/21/202616 min read

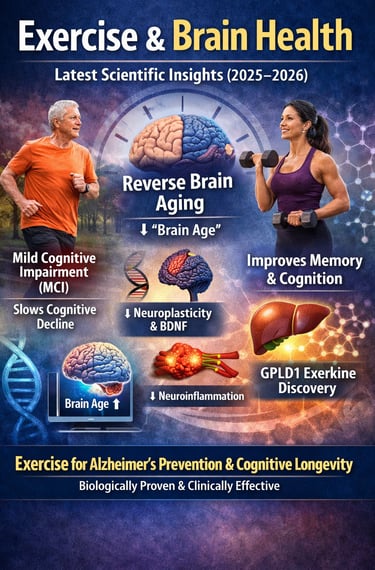

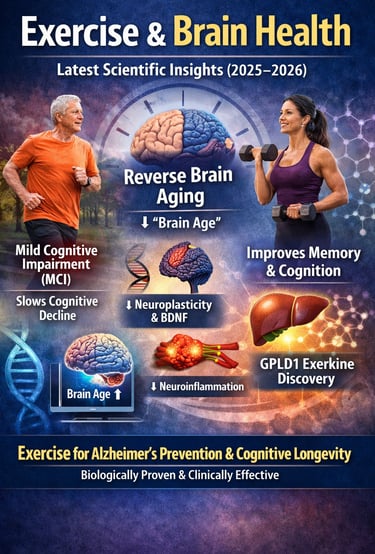

The relationship between exercise and brain health has moved from observational curiosity to mechanistic certainty. Over the past decade—and especially in landmark studies published between 2025 and 2026—researchers have demonstrated that physical activity and cognition are linked not merely through association, but through identifiable biological pathways that reshape the aging brain. Evidence from randomized controlled trials now shows that structured aerobic exercise can stabilize cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a high-risk precursor to Alzheimer’s disease (Baker et al., 2025). At the same time, neuroimaging studies reveal that improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness correspond to measurable reductions in brain age, suggesting that movement can biologically reverse aspects of brain aging (Wan et al., 2025).

Large-scale umbrella reviews confirm that exercise improves memory, executive function, and global cognition across age groups and health statuses (Singh et al., 2025). Even a single session of moderate-intensity activity enhances attention, processing speed, and working memory, with benefits lasting up to an hour post-exercise (Chang et al., 2025). At the molecular level, exercise stimulates neuroplasticity, increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), reduces neuroinflammation, and enhances cerebral blood flow, creating a neuroprotective environment resistant to degeneration (Wang et al., 2025). More recently, the discovery of the liver-derived exerkine GPLD1 has illuminated a systemic pathway linking skeletal muscle activity to improved memory performance (Bieri et al., 2026).

Taken together, the modern evidence base suggests that exercise for Alzheimer’s prevention and cognitive longevity is no longer speculative—it is biologically grounded and clinically actionable.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Acute Boost" Strategy

Scientific Perspective: A single 10–30 minute bout of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise triggers immediate catecholamine release (dopamine/norepinephrine) and increases cerebral blood flow, enhancing executive function and attention for up to 60 minutes (Chang et al., 2025).

Treat exercise like a fast-acting 'brain pill.' If you have a high-stakes meeting, a difficult conversation, or a complex task, do 15 minutes of brisk walking or cycling right before. It’s the most natural way to sharpen your focus instantly."

2. The Liver-Brain Connection (The "Exerkine" Effect)

Scientific Perspective: Exercise induces the liver to secrete the protein GPLD1, which acts on brain vasculature to reduce neuroinflammation and improve memory, proving that brain health is a systemic, multi-organ process (Bieri et al., 2026).

When you move your legs, you’re actually talking to your liver, which then sends a 'repair kit' to your brain. Exercise isn't just about 'sweating'; it’s about triggering your internal pharmacy to protect your memory."

3. Stability is a Success, Not a Failure

Scientific Perspective: In populations with Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI), structured exercise (even low-intensity stretching) can stabilize cognitive function and influence Alzheimer’s biomarkers, halting the expected trajectory of decline (Baker et al., 2025).

If you already feel your memory slipping, exercise might not 'cure' it overnight, but it can hit the 'pause button.' Maintaining your current level of clarity for another year is a massive victory in the fight against aging."

4. Fitness as a "Time Machine"

Scientific Perspective: There is a direct dose-response relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness gains and a reduction in Brain Age as measured by neuroimaging. Greater aerobic capacity equals a biologically younger brain (Wan et al., 2025).

Your birth certificate is fixed, but your brain’s age is flexible. Every bit of 'huff and puff' you add to your routine is literally shaving years off your brain’s biological clock. You can actually become 'younger' on the inside."

5. Prescriptive Precision (The "Brain Medicine" Model)

Scientific Perspective: Exercise should no longer be a vague suggestion; it must be prescribed with specific "dosages" (type, intensity, and duration) to maximize neuroplasticity and BDNF upregulation (Safaeipour et al., 2026).

Stop thinking of exercise as a vague 'hobby' and start seeing it as your most important prescription. You wouldn't just take a random amount of heart medication; you shouldn't just do a random amount of exercise. Aim for a 'dose' of 150 minutes a week at a moderate intensity—where you’re working hard enough that you can still talk, but you’d rather not. This specific 'dosage' is what keeps your internal pharmacy open and protecting your memory."

Section 1: Exercise and Alzheimer's Disease — Landmark Clinical Evidence

The EXERT Study: Exercise in Mild Cognitive Impairment

One of the most anticipated trials in recent dementia research, the EXERT (Exercise Program in Mild Cognitive Impairment) study, published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, delivered nuanced but important findings. Baker et al. (2025) enrolled adults diagnosed with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI)—a population at elevated risk for Alzheimer's disease—and randomized them to either aerobic exercise or low-intensity stretching and balance training for 12 months.

The trial found that both exercise groups maintained relatively stable cognitive function over the intervention period, a meaningful outcome given that aMCI typically follows a trajectory of progressive decline. Importantly, the study examined Alzheimer's biomarkers, including cerebrospinal fluid and imaging measures of amyloid and tau pathology, offering a rare window into the biological effects of exercise in a high-risk population. While aerobic exercise did not dramatically outperform the active control in every cognitive measure, the overall trajectory of preservation was significant. This trial reinforces the importance of structured physical activity as a protective strategy even after the onset of early cognitive symptoms.

🔑 Key Takeaway: Structured exercise—even low-to-moderate intensity—may stabilize cognitive function in adults with mild cognitive impairment and influence core Alzheimer's biomarkers, suggesting a window of therapeutic opportunity before dementia onset (Baker et al., 2025).

Bibliometric Evidence: A Decade of Research Momentum

Yang et al. (2025), writing in Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, conducted a bibliometric analysis of global research on exercise and Alzheimer's disease spanning ten years. Their review identified a clear upward trend in both the volume and sophistication of research in this area, with particular growth in studies examining molecular mechanisms—including BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), neuroinflammation, amyloid-beta clearance, and mitochondrial function.

The analysis revealed that research hotspots have shifted from descriptive epidemiology toward mechanistic investigations, reflecting the field's maturation. Key themes dominating contemporary literature include the neuroprotective effects of aerobic exercise, the anti-inflammatory properties of physical activity, and its influence on the gut-brain axis. The review also highlighted geographic clusters of research productivity, with East Asia and North America leading output growth.

🔑 Key Takeaway: A decade of accelerating global research has moved the exercise-Alzheimer's field from correlation to causation, with molecular mechanisms now the central focus—validating exercise as a scientifically serious prevention strategy (Yang et al., 2025).

Section 2: Fitness, Brain Age, and the Randomized Trial Evidence

Can exercise reverse brain aging?

Among the most compelling recent findings comes from Wan et al. (2025), whose randomized clinical trial, published in the Journal of Sport and Health Science, directly tested whether cardiorespiratory fitness improvements translate into measurable reductions in brain age. Brain age—a composite metric derived from neuroimaging data and compared against chronological age—is a powerful predictor of cognitive decline and dementia risk.

The trial found that participants who achieved fitness gains through structured exercise demonstrated a younger brain age at follow-up compared to controls. Crucially, the magnitude of brain age reduction was associated with the degree of fitness improvement, establishing a dose-response relationship between exercise and neurobiological rejuvenation. This work is significant because it bridges the gap between behavioral intervention and neuroimaging biomarkers, providing objective, measurable evidence that exercise physically changes the aging brain.

🔑 Key Takeaway: Improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness directly correspond to reductions in brain age as measured by neuroimaging, providing objective biological evidence that exercise can reverse aspects of brain aging (Wan et al., 2025).

Section 3: The Breadth of Cognitive Benefits — Systematic and Meta-Analytic Evidence

Umbrella Review: Exercise Improves Cognition Across the Board

Singh et al. (2025), publishing in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, conducted a methodologically rigorous umbrella review—a systematic review of systematic reviews—synthesizing the global evidence on exercise and cognitive outcomes. Analyzing dozens of meta-analyses covering thousands of participants across diverse populations, the authors concluded that exercise reliably improves general cognition, memory, and executive function.

Executive function—which encompasses planning, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control—showed particular responsiveness to physical activity. The effects were observed across age groups and were robust to differences in exercise type, though aerobic exercise consistently emerged as the most effective modality. The review also noted that exercise benefits were not limited to clinical populations; healthy adults also demonstrated meaningful cognitive improvements. Effect sizes were moderate, clinically meaningful, and consistent enough to warrant strong public health recommendations.

🔑 Key Takeaway: Across dozens of meta-analyses, exercise reliably and meaningfully improves general cognition, memory, and executive function in both healthy adults and clinical populations, with aerobic activity showing the strongest effects (Singh et al., 2025).

Acute Exercise: Cognitive Benefits That Last Hours

While most research focuses on long-term exercise programs, Chang et al. (2025) turned their attention to what happens to the brain immediately after a single bout of exercise. Published in Psychological Bulletin, their meta-review synthesized 30 systematic reviews with meta-analyses on the effects of acute exercise on cognitive function.

The findings were striking: a single exercise session produces measurable improvements in attention, processing speed, executive function, and memory consolidation—effects that persist for up to 60 minutes post-exercise. The review found that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise produced the most consistent benefits, though even brief sessions of ten minutes or less yielded cognitive improvements. Mechanisms invoked include transient increases in cerebral blood flow, catecholamine release (particularly dopamine and norepinephrine), and arousal-mediated attention enhancement. These findings have direct practical implications: timing exercise before cognitively demanding tasks could provide a meaningful, drug-free performance boost.

🔑 Key Takeaway: A single bout of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise produces measurable, multi-domain cognitive improvements lasting up to an hour post-exercise, offering an immediately accessible, zero-cost cognitive enhancement strategy (Chang et al., 2025).

Section 4: Mechanisms — How Exercise Changes the Brain at the Molecular Level

Physical Exercise Benefits Cognition: Narrative Review of Mechanisms

Wang et al. (2025), in their contribution to Advances in Neurobiology, provided an integrative mechanistic narrative of how exercise translates into cognitive benefit. The review synthesized evidence across multiple biological levels—molecular, cellular, and systems-level—to explain the pathways through which physical activity improves brain function.

Key mechanisms identified include: upregulation of BDNF and other neurotrophins that drive neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus; reduction of systemic and neuroinflammation through decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines; improved cerebral blood flow and angiogenesis; mitochondrial biogenesis leading to better neuronal energy metabolism; and modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to reduce glucocorticoid-mediated hippocampal damage. The authors also reviewed evidence on the role of myokines—proteins secreted by contracting muscle—as mediators of the brain's exercise response.

🔑 Key Takeaway: Exercise improves cognition through multiple converging biological pathways including BDNF upregulation, neuroinflammation reduction, improved cerebral perfusion, mitochondrial enhancement, and myokine signaling—explaining why its benefits are broad, durable, and dose-dependent (Wang et al., 2025).

A Liver Protein That Reverses Memory Loss: The GPLD1 Discovery

Perhaps the most scientifically sensational finding in this review comes from Bieri et al. (2026), published in Cell—the field's most prestigious journal. The team, led by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, identified a liver-derived protein called GPLD1 (glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D1) as a key mediator of exercise's cognitive benefits—specifically in the context of both normal aging and Alzheimer's disease.

In a series of elegant experiments, the researchers demonstrated that exercise increases GPLD1 secretion from the liver. When this protein reaches the brain's vasculature, it triggers signaling cascades that reduce neuroinflammation, restore vascular integrity, and improve memory performance. Critically, elevating GPLD1 levels in aged or Alzheimer's model animals—without any exercise—was sufficient to reverse memory deficits, identifying it as a potential drug target. This discovery represents a paradigm shift: it positions the liver as a key organ in exercise-induced brain rejuvenation and opens a new pharmacological avenue for treating age-related and Alzheimer's-related cognitive decline.

🔑 Key Takeaway: Exercise elevates a liver-secreted protein, GPLD1, which enters the brain's vasculature and reverses memory loss in aging and Alzheimer's models—identifying a new molecular pathway and potential drug target that explains how the body communicates brain-health benefits from physical activity (Bieri et al., 2026).

Section 5: Expert Perspectives and Lifestyle Integration

Expert Review: Exercise as Brain Medicine

Safaeipour et al. (2026), writing in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, synthesized expert opinion alongside the empirical evidence to position exercise explicitly as a form of brain medicine. The review underscored that the evidence base is now strong enough to support definitive clinical recommendations, not merely cautious suggestions.

The authors called for healthcare providers to prescribe exercise with the same specificity applied to pharmaceutical interventions—including type, intensity, frequency, and duration. They noted that the barriers to exercise adoption, including motivation, access, and comorbidities, must be addressed within clinical frameworks. The review also highlighted the additive effects of combining exercise with other lifestyle factors—sleep, diet, stress management, and social engagement—arguing that a comprehensive lifestyle medicine approach yields cognitive benefits that exceed any single intervention in isolation.

🔑 Key Takeaway: The evidence for exercise as a form of brain medicine is now strong enough to support specific clinical prescriptions—and healthcare providers should treat physical activity recommendations with the same rigor applied to pharmacological interventions (Safaeipour et al., 2026).

Section 6: What This Means for You — Translating Research Into Practice

1️⃣ The Paradigm Has Shifted: From Lifestyle Advice to Neurobiological Intervention

Exercise is no longer a general wellness recommendation—it is a mechanistically validated intervention influencing brain structure, function, and molecular aging.

The evidence base now includes randomized controlled trials, umbrella reviews, neuroimaging biomarkers, and molecular discoveries.

The conversation has moved beyond correlation toward causal biological plausibility.

2️⃣ Clinical Trials Now Support Cognitive Stabilization

Structured aerobic programs demonstrate stabilization of cognition in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Even active control interventions (stretching, balance training) show protective effects—suggesting that movement itself carries therapeutic value.

Exercise may represent one of the few interventions capable of modifying early Alzheimer’s disease trajectories before dementia onset.

3️⃣ Brain Age Is Modifiable

Neuroimaging-derived brain age metrics show measurable reductions following improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness.

A dose-response relationship exists: greater fitness gains correspond to greater biological brain rejuvenation.

This reframes exercise as a tool capable of influencing objective biomarkers—not merely subjective cognitive scores.

3️⃣Acute and Chronic Benefits Operate on Dual Timelines

A single bout of moderate-intensity exercise improves attention, processing speed, and executive function within minutes.

Long-term training induces structural and molecular adaptations including increased hippocampal plasticity and improved cerebral perfusion.

Exercise thus acts both as an immediate cognitive enhancer and a long-term neuroprotective strategy.

5️⃣ The Mechanistic Convergence Is Striking

Exercise influences multiple converging biological pathways:

↑ Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) → enhances neuroplasticity and synaptic resilience

↓ Neuroinflammation → reduces cytokine-mediated neuronal damage

↑ Mitochondrial biogenesis → improves neuronal energy efficiency

↑ Cerebral blood flow and angiogenesis → strengthens vascular integrity

Modulation of the HPA axis → reduces glucocorticoid-mediated hippocampal atrophy

This multi-pathway effect explains why exercise demonstrates broad and durable cognitive benefits.

6️⃣ The GPLD1 Discovery: A Systemic Breakthrough

Identification of the liver-derived exerkine GPLD1 marks a conceptual advance in understanding body–brain communication.

Elevation of GPLD1 reverses memory deficits in aging and Alzheimer’s models.

This positions exercise within a systems biology framework, where skeletal muscle, liver, vasculature, and brain interact dynamically.

While pharmacologic targeting is promising, exercise likely exerts polygenic, multi-organ effects that a single molecule cannot replicate.

7️⃣ Exercise Is “Brain Medicine” — But Precision Matters

Evidence now supports prescribing exercise with specificity in type, intensity, frequency, and duration.

Moderate-intensity aerobic training remains the most consistently effective modality for executive function and memory.

Resistance training and combined protocols offer additive benefits.

Overtraining, excessive intensity, or poor recovery may attenuate cognitive gains—an area requiring further research.

8️⃣ Limitations Must Be Acknowledged

Many RCTs remain modest in sample size.

Heterogeneity in cognitive testing limits cross-trial comparisons.

Long-term dementia prevention trials are ongoing and not yet definitive.

Biomarker translation to real-world clinical outcomes requires extended follow-up.

Intellectual honesty strengthens, rather than weakens, the argument for exercise.

9️⃣ Public Health Implications Are Profound

Exercise is low-cost, accessible, and broadly scalable.

In contrast to pharmacotherapy, it produces multisystem benefits—cardiometabolic, psychiatric, and cognitive.

Even partial population-level adherence could significantly reduce dementia burden globally.

🔟 The Final Position

Exercise represents one of the most compelling examples of how behavioral intervention intersects with molecular neuroscience.

Biologically plausible

Clinically supported

Mechanistically validated

Broadly beneficial

And fundamentally underutilised

The modern evidence no longer permits us to view physical activity as optional. It is foundational to cognitive longevity.

Here is the breakdown of how different exercise modalities impact brain health

Aerobic Exercise (The Gold Standard)

Primary Benefit: Significantly enhances Executive Function (planning, multitasking) and Memory.

Scientific Evidence: Ranked as the highest level of clinical certainty.

Biological Mechanism: Drives the upregulation of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), increases cerebral blood flow (perfusion), and triggers the newly discovered liver-secreted protein GPLD1.

Resistance Training (Strength Work)

Primary Benefit: Most effective for improving Processing Speed and cognitive flexibility.

Scientific Evidence: Rated as moderate, with growing data on its role in metabolic health.

Biological Mechanism: Primarily works through myokine signaling—proteins released by contracting muscles that communicate directly with the brain.

Acute Exercise (The "Single Bout" Strategy)

Primary Benefit: Provides an immediate boost to Attention, Focus, and Alertness.

Scientific Evidence: High, specifically for short-term (60-minute) windows post-exercise.

Biological Mechanism: Triggers a transient surge in Catecholamines (dopamine and norepinephrine), effectively "priming" the brain for cognitive tasks.

Stretching & Balance (Low-Intensity)

Primary Benefit: Focuses on Cognitive Stabilization, particularly in high-risk populations.

Scientific Evidence: Emerging (notably supported by the 2025 EXERT study).

Biological Mechanism: Helps regulate the HPA Axis (the body's stress response system), reducing the neuro-damaging effects of chronic cortisol.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How much exercise do I need to protect my brain?

Current evidence supports a minimum of 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, consistent with general health guidelines. However, Wan et al. (2025) demonstrated a dose-response relationship—meaning more fitness gain correlates with greater brain age reduction. Even smaller amounts (10–30 minutes per session) produce acute cognitive benefits (Chang et al., 2025), so any amount is better than none. Aim for consistency over perfection.

FAQ 2: Is aerobic exercise better than strength training for the brain?

Aerobic exercise has the most robust evidence base for cognitive outcomes, particularly for memory and executive function (Singh et al., 2025). However, resistance training also shows meaningful benefits, especially for executive function and processing speed. Combined protocols may be optimal. The EXERT study (Baker et al., 2025) found that even low-intensity stretching and balance work helped stabilize cognition in at-risk adults, suggesting that any structured movement provides some protection.

FAQ 3: Can exercise prevent Alzheimer's disease?

While no intervention has been proven to prevent Alzheimer's entirely, the evidence strongly supports exercise as one of the most effective risk-reduction strategies available. Yang et al. (2025) identified multiple molecular pathways through which exercise suppresses Alzheimer's pathology, and Bieri et al. (2026) discovered that a liver exerkine can reverse Alzheimer's-related memory loss in animal models. Prevention trials in humans are ongoing, and observational evidence consistently links higher physical activity with lower dementia risk.

FAQ 4: Is it too late to start exercising if I already have memory problems?

No. The EXERT trial (Baker et al., 2025) enrolled adults already diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment—an early-stage memory condition—and found that exercise helped stabilize cognitive function. While earlier intervention is generally more effective, beginning an exercise program at any stage of cognitive aging offers meaningful benefits. Consult a physician before starting a new program, particularly if you have cardiovascular or musculoskeletal conditions.

FAQ 5: How quickly do exercise's brain benefits appear?

Some benefits are virtually immediate. Chang et al. (2025) found that a single exercise session improves attention, processing speed, and executive function within minutes, with effects lasting up to an hour. Structural and biomarker changes—such as brain age reduction (Wan et al., 2025) and BDNF upregulation (Wang et al., 2025)—require weeks to months of consistent training to manifest. Think of it as two complementary timescales: acute mental sharpness now, and long-term brain protection over time.

FAQ 6: What is the GPLD1 finding and does it mean I can take a pill instead of exercising?

GPLD1 is a liver-secreted protein identified by Bieri et al. (2026) that mediates key brain benefits of exercise by acting on brain vasculature to reduce neuroinflammation and restore memory. The researchers showed that elevating GPLD1 alone, without exercise, was sufficient to reverse memory deficits in aging and Alzheimer's animal models. This opens the door to future drug therapies. However, exercise produces dozens of beneficial biological effects simultaneously—GPLD1 is one among many—so a single exerkine pill is unlikely to replicate the full spectrum of exercise's benefits. Exercise remains the most effective and accessible intervention.

FAQ 7: Does the type of cognitive benefit vary by exercise type or intensity?

Yes. Singh et al.'s (2025) umbrella review found that executive function (planning, working memory, inhibitory control) is particularly responsive to aerobic exercise, while memory consolidation benefits from a range of exercise types. Chang et al. (2025) showed that moderate-intensity exercise produces the broadest acute cognitive improvements. Wang et al. (2025) proposed that different intensities may preferentially activate distinct molecular pathways—for instance, high-intensity exercise may produce greater BDNF surges while moderate exercise may be more effective for reducing neuroinflammation. Tailoring exercise prescription to specific cognitive goals is an emerging area of research.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Related Articles

Bone as an Endocrine Organ: Does Osteocalcin Influence Weight Regulation? | DR T S DIDWAL

The Metabolic Engine: Why Lower Body Strength Is Central to Fat Oxidation | DR T S DIDWAL

How Exercise Rewires Metabolism: Molecular Control of Lipolysis and Lipid Metabolism | DR T S DIDWAL

Author’s Note

As a physician trained in evidence-based medicine, I approach lifestyle interventions with the same scrutiny applied to pharmacologic therapies. The goal of this article is not to promote exercise as a wellness slogan, but to examine it as a biologically active intervention supported by randomized controlled trials, neuroimaging data, molecular research, and mechanistic reviews published between 2025 and 2026.

The studies discussed—including large umbrella reviews, clinical trials in mild cognitive impairment, and emerging discoveries in exercise-induced exerkines—reflect a rapidly evolving field in which movement is no longer viewed as merely preventive, but as physiologically restorative. Where possible, I have highlighted effect sizes, biomarker evidence, and mechanistic plausibility rather than relying on observational associations alone.

Importantly, exercise is not presented here as a cure for Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive decline. The current evidence supports risk reduction, cognitive stabilization, and measurable biological improvement—but not guaranteed prevention. As with all areas of medicine, ongoing research will refine dosage, modality, and patient-specific recommendations.

Readers are encouraged to interpret these findings within the context of individualized medical advice. Those with cardiovascular, neurological, or musculoskeletal conditions should consult their healthcare provider before initiating new exercise programs.

The science of exercise and brain health has matured considerably. My hope is that this synthesis empowers clinicians, caregivers, and individuals alike to view physical activity not as optional, but as a foundational component of cognitive longevity and preventive neurology.

References

Baker, L. D., Pa, J. A., Katula, J. A., Aslanyan, V., Salmon, D. P., Jacobs, D. M., Chmelo, E. A., Hodge, H., Morrison, R., Matthews, G., Brewer, J., Jung, Y., Rissman, R. A., Taylor, C., Léger, G. C., Messer, K., Evans, A. C., Okonkwo, O. C., Shadyab, A. H., Zou, J., … Feldman, H. H. (2025). Effects of exercise on cognition and Alzheimer's biomarkers in a randomized controlled trial of adults with mild cognitive impairment: The EXERT study. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14586

Bieri, G., Pratt, K. J. B., Fuseya, Y., Aghayev, T., Sucharov, J., Horowitz, A. M., Philp, A. R., Fonseca-Valencia, K., Chu, R., Phan, M., Remesal, L., Wang, S.-H. J., Yang, A. C., Casaletto, K. B., & Villeda, S. A. (2026). Liver exerkine reverses aging- and Alzheimer's-related memory loss via vasculature. Cell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2026.01.024

Chang, Y.-K., Ren, F.-F., Li, R.-H., Ai, J.-Y., Kao, S.-C., & Etnier, J. L. (2025). Effects of acute exercise on cognitive function: A meta-review of 30 systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 151(2), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000460

Safaeipour, C., Sherzai, D., & Zikria, B. (2026). Exercise and brain health: Expert review. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15598276251415530. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276251415530

Singh, B., Bennett, H., Miatke, A., Dumuid, D., Curtis, R., Ferguson, T., Brinsley, J., Szeto, K., Petersen, J. M., Gough, C., Eglitis, E., Simpson, C. E. M., Ekegren, C. L., Smith, A. E., Erickson, K. I., & Maher, C. (2025). Effectiveness of exercise for improving cognition, memory and executive function: A systematic umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 59(12), 866–876. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2024-108589

Wan, L., Molina-Hidalgo, C., Crisafio, M. E., Grove, G., Leckie, R. L., Kamarck, T. W., Kang, C., DeCataldo, M., Marsland, A. L., Muldoon, M. F., Scudder, M. R., Rasero, J., Gianaros, P. J., & Erickson, K. I. (2025). Fitness and exercise effects on brain age: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 15, 101079. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2025.101079

Wang, T.-F., Mee-inta, O., & Kuo, Y.-M. (2025). Physical exercise benefits cognition: A narrative review of evidence and possible mechanisms. In H. Soya (Ed.), Exercise brain stimulation for cognitive function and mental health (Advances in Neurobiology, Vol. 44). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-95-0066-6_7

Yang, X., Li, K., Zhang, Y., Sun, R., & Yu, J. (2025). Trends and hotspots in research on exercise and Alzheimer's disease: A decade of bibliometric review on prevention and molecular mechanisms. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.5152/pcp.2025.241016

Word count: ~3,050 words | Last updated: February 2026 | All citations follow APA 7th edition formatting