Frailty Syndrome: How Sarcopenia Fits Into the Frailty Cycle

Discover how sarcopenia drives frailty syndrome and accelerates functional decline in older adults. Explore the Fried Frailty Criteria, the muscle-mitochondria link, and evidence-based strategies—exercise, nutrition, and emerging therapies—to prevent and reverse frailty, improve independence, and enhance quality of life.

SARCOPENIA

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

11/28/202514 min read

If you've ever watched a loved one struggle with everyday tasks that once seemed effortless—climbing stairs, carrying groceries, or simply getting out of a chair—you've witnessed the visible face of frailty syndrome. But what's happening beneath the surface? The answer lies in a complex interplay between muscle loss, mitochondrial dysfunction, and a cascade of biological changes that define the frailty cycle. Understanding how sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) drives this cycle isn't just academic—it's essential for protecting our health as we age.

Recent research has revolutionized our understanding of frailty, revealing that it's not an inevitable consequence of aging but a preventable and potentially reversible condition. This comprehensive guide explores the intricate relationship between sarcopenia and frailty, examines the Fried Frailty Criteria, distinguishes between physical and cognitive frailty, and uncovers the critical muscle-mitochondria link. We'll also dive deep into the concerning connection between sarcopenia and heart failure, providing you with actionable insights backed by cutting-edge science.

Clinical Pearls

Sarcopenia Accelerates Frailty Transitions and Impedes Recovery: Sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss, is the key physiological driver that significantly accelerates the transition from a robust to a pre-frail or frail state (Álvarez-Bustos et al., 2022). Crucially, its presence also impedes recovery, making it harder for frail individuals to transition back to healthier states. Therefore, early, objective screening for sarcopenia (via grip strength, gait speed, and muscle mass assessment) in all older adults, especially those classified as pre-frail, is essential for implementing timely interventions that break the downward spiral before severe decline.

The Muscle-Mitochondria Link is the Core Therapeutic Target: At the cellular level, sarcopenia and frailty are driven by mitochondrial dysfunction, characterized by accumulated mitochondrial DNA mutations, impaired dynamics, and inefficient mitophagy (Sato et al., 2024; Viña & Gomez-Cabrera, 2025). This results in energy-starved, damaged muscle fibers. Clinically, this makes exercise—particularly progressive resistance training—the single most effective therapy, as it uniquely stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control, thereby rejuvenating aging muscle and improving overall energy capacity.

Frailty Screening is Mandatory in Chronic Illness, Especially Heart Failure: Frailty syndrome is not an inevitable consequence of aging but a state of reduced physiological reserve, strongly linked to chronic conditions (Sato et al., 2024). In Heart Failure (HF) patients, sarcopenia is particularly prevalent and creates a dangerous vicious cycle, significantly increasing mortality, hospitalization rates, and reducing exercise tolerance (Dodds & Sayer, 2016). Routine, objective frailty and sarcopenia screening should be integrated into HF and geriatric clinics to facilitate multidisciplinary care combining cardiac rehabilitation, optimized nutrition, and tailored resistance training.

Optimal Protein Intake is Higher and Needs Distribution: To counteract the catabolic state of sarcopenia and chronic inflammation, older adults require significantly higher protein intake than younger individuals. The clinical goal should be 1.0–1.2 g protein/kg body weight/day for maintenance, increasing to 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day for those with active sarcopenia or illness (Viña & Gomez-Cabrera, 2025). Furthermore, promoting the distribution of protein to ensure 25–30g of high-quality, leucine-rich protein at each major meal is necessary to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis (Viña & Gomez-Cabrera, 2025).

Frailty is a Multidimensional Syndrome that Requires Holistic Intervention: Frailty is defined by the loss of resilience across multiple domains (physical, cognitive, social), not just muscle mass (Blumer & Le, 2025). Therefore, reversing frailty requires a holistic, multidisciplinary approach that goes beyond exercise and nutrition. Effective management must also address chronic inflammation (inflammaging), optimize Vitamin D status, review medications that promote muscle loss, and combat social isolation and cognitive decline to successfully transition patients from a frail or pre-frail state back toward robustness.

.

Understanding Frailty Syndrome: More Than Just Getting Old

Frailty syndrome represents a state of increased vulnerability to stressors, characterized by reduced physiological reserves across multiple organ systems. Think of frailty as your body's decreasing ability to bounce back from challenges—whether that's recovering from a fall, fighting off an infection, or adapting to medication changes.

According to Sato et al. (2024), frailty is fundamentally a multidimensional syndrome involving physical, cognitive, and social components that dramatically increase the risk of adverse health outcomes, including disability, hospitalization, and mortality. The research emphasizes that frailty isn't simply about chronological age—it's about biological age and the accumulated deficits that erode our resilience

The Fried Frailty Criteria: The Gold Standard

The Fried Frailty Phenotype, also known as the Fried Frailty Criteria, remains the most widely used tool for identifying frailty in clinical practice. This validated assessment identifies five key components:

Unintentional weight loss (≥10 pounds in the past year)

Self-reported exhaustion (feeling tired most of the time)

Weak grip strength (measured objectively)

Slow walking speed (decreased gait velocity)

Low physical activity levels (reduced energy expenditure)

Individuals meeting three or more criteria are classified as frail, while those meeting one or two are considered pre-frail. This phenotypic approach has proven remarkably effective at predicting adverse outcomes, but it's just one piece of the puzzle (Dodds & Sayer, 2016).

Dodds and Sayer (2016) highlight that the Fried criteria provide a practical framework for clinicians to identify vulnerable older adults who would benefit from targeted interventions. Their research underscores that early identification using these criteria enables proactive management before irreversible decline occurs.

Physical vs Cognitive Frailty: Two Sides of the Same Coin

While the Fried criteria focus primarily on physical frailty, emerging evidence reveals that cognitive frailty represents an equally important dimension of this syndrome. Physical frailty manifests through the five criteria mentioned above, directly impacting mobility, strength, and physical function.

Cognitive frailty, conversely, involves the presence of physical frailty alongside cognitive impairment (excluding dementia), creating a particularly vulnerable state. Blumer and Le (2025) emphasize the importance of distinguishing between these two dimensions, noting that they often coexist and synergistically accelerate functional decline. Their research advocates for a more nuanced approach that recognizes sarcopenia and frailty as distinct yet interrelated conditions requiring different assessment strategies.

The researchers argue that current clinical practice often conflates these conditions, leading to suboptimal treatment approaches. By recognizing that sarcopenia (muscle loss) and frailty (multidimensional vulnerability) represent overlapping but non-identical constructs, clinicians can develop more targeted interventions addressing both muscle health and overall resilience (Blumer & Le, 2025).

Sarcopenia: The Muscle Loss Driving Frailty

Sarcopenia, derived from Greek words meaning "poverty of flesh," describes the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function that occurs with aging. It's not just about looking less muscular—sarcopenia fundamentally impairs your ability to perform daily activities and maintain independence.

The Biological Basis of Sarcopenia

Viña and Gomez-Cabrera (2025) provide groundbreaking insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying sarcopenia and frailty. Their research identifies several key pathways:

Oxidative stress plays a central role, with age-related increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelming cellular antioxidant defenses. This oxidative damage affects both muscle fibers and the mitochondria that power them, creating a vicious cycle of declining function. Chronic inflammation, often termed "inflammaging," creates a hostile environment for muscle maintenance. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α actively promote muscle protein breakdown while inhibiting protein synthesis—a double hit that accelerates sarcopenia.

Hormonal changes compound these effects. Declining levels of anabolic hormones including testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1, reduce the body's capacity to build and maintain muscle tissue. Simultaneously, increased cortisol levels from chronic stress states further promote muscle catabolism .

The researchers also highlight mitochondrial dysfunction as a critical driver, noting that age-related declines in mitochondrial quality and quantity directly impair muscle energy production, contributing to both sarcopenia and frailty (Viña & Gomez-Cabrera, 2025).

The Muscle-Mitochondria Link: Your Cellular Powerhouses

The connection between muscle health and mitochondrial function deserves special attention because it represents one of the most promising therapeutic targets. Mitochondria are the cellular powerhouses that generate ATP, the energy currency your muscles need to contract and function.

Sato et al. (2024) explain that mitochondrial dysfunction in aging muscle manifests through multiple mechanisms. Mitochondrial DNA mutations accumulate over time, impairing the production of critical respiratory chain proteins. Mitochondrial dynamics—the processes of fusion and fission that maintain mitochondrial health—become dysregulated, leading to fragmented, dysfunctional mitochondria .

Perhaps most importantly, mitophagy—the cellular process that removes damaged mitochondria—becomes less efficient with age. This allows dysfunctional mitochondria to accumulate, producing excessive ROS while failing to generate adequate energy. The result? Muscle fibers become energy-starved and increasingly damaged, accelerating sarcopenic decline .

The muscle-mitochondria link also explains why exercise remains the most effective intervention for sarcopenia. Physical activity stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis (the creation of new mitochondria), improves mitochondrial quality control, and enhances overall energy production capacity—essentially rejuvenating aging muscle at the cellular level .

How Sarcopenia Drives the Frailty Cycle

Understanding the frailty cycle is crucial because it reveals how sarcopenia creates a self-perpetuating spiral of decline. Álvarez-Bustos et al. (2022) conducted a landmark population-based cohort study examining how sarcopenia influences transitions between frailty states over time.

Key Findings from the Population Study

This Spanish cohort study followed 1,740 community-dwelling older adults, providing unprecedented insights into the dynamic relationship between sarcopenia and frailty. The researchers found that:

Sarcopenia significantly accelerates frailty progression. Individuals with sarcopenia were substantially more likely to transition from robust to pre-frail states, or from pre-frail to frail states, compared to those without sarcopenia .

The presence of sarcopenia reduces the likelihood of improvement. Perhaps most concerning, participants with sarcopenia showed significantly lower rates of transitioning from frail to pre-frail states, or from pre-frail to robust states. In other words, sarcopenia doesn't just accelerate decline—it also impedes recovery .

Sarcopenia's impact varies by initial frailty state. The researchers discovered that sarcopenia's effect was particularly pronounced in individuals starting from robust or pre-frail states, suggesting that early intervention might be most effective before severe frailty develops (Álvarez-Bustos et al., 2022).

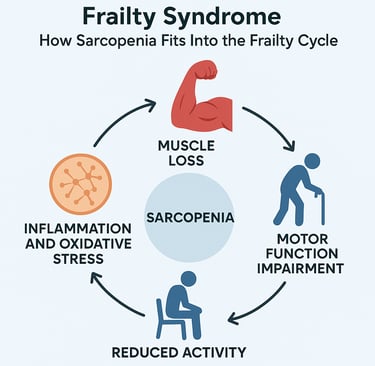

The Vicious Cycle Explained

The frailty cycle works like this: Muscle loss from sarcopenia reduces physical capability, leading to decreased activity. Reduced activity accelerates further muscle loss and mitochondrial dysfunction. Weaker muscles increase fall risk and reduce mobility, promoting social isolation and inadequate nutrition. Poor nutrition fails to provide the protein and nutrients needed to maintain muscle, accelerating sarcopenic decline. Meanwhile, chronic inflammation and oxidative stress continue damaging remaining muscle tissue and impairing recovery capacity.

This cycle explains why frailty can progress so rapidly once it begins, and why breaking the cycle requires multifaceted interventions addressing muscle health, nutrition, inflammation, and physical activity simultaneously.

Sarcopenia and Heart Failure: A Dangerous Combination

The intersection of sarcopenia and heart failure represents one of the most challenging clinical scenarios in geriatric medicine. Heart failure itself promotes muscle wasting through multiple mechanisms, while sarcopenia worsens heart failure outcomes—creating another vicious cycle.

Why Heart Failure Causes Sarcopenia

Sato et al. (2024) detail the complex pathophysiology linking heart failure to sarcopenia:

Reduced cardiac output limits oxygen and nutrient delivery to skeletal muscles, impairing their metabolic function and promoting atrophy. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure increases circulating levels of catecholamines, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, all of which promote muscle protein breakdown.

Chronic inflammation is particularly severe in heart failure patients, with markedly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines directly inducing muscle wasting. This cardiac cachexia represents an extreme form of sarcopenia associated with particularly poor outcomes (Sato et al., 2024).

Reduced physical activity due to fatigue and dyspnea creates deconditioning, accelerating sarcopenic decline. Many heart failure patients become trapped in a cycle where weakness prevents exercise, and lack of exercise worsens weakness.

How Sarcopenia Worsens Heart Failure

The relationship works both ways. Sarcopenia in heart failure patients predicts:

Increased mortality risk: Studies show that sarcopenic heart failure patients have significantly higher death rates than non-sarcopenic patients with similar cardiac function

Higher hospitalization rates: Weakness and reduced functional capacity increase vulnerability to decompensation

Impaired exercise capacity: Sarcopenia limits rehabilitation potential and exercise tolerance

Poor quality of life: Muscle weakness directly impacts the ability to perform daily activities, reducing independence

Dodds and Sayer (2016) emphasize that sarcopenia screening should be routine in heart failure clinics, as identifying muscle loss early enables targeted interventions that can improve both cardiac and functional outcomes.

Diagnosis and Assessment: Identifying the Problem

Accurate diagnosis of both sarcopenia and frailty requires systematic assessment using validated tools. Viña and Gomez-Cabrera (2025) outline comprehensive diagnostic approaches:

Assessing Sarcopenia

Muscle mass can be measured using:

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA): The gold standard for body composition

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA): More accessible but less precise

CT or MRI: Most accurate but expensive and not practical for routine screening

Muscle strength assessment includes:

Grip strength: Simple, validated, and highly predictive of outcomes

Chair stand test: Measures lower extremity strength

Knee extension strength: Specific assessment of quadriceps function

Physical performance evaluation involves:

Gait speed: Walking 4 meters at usual pace (speeds <0.8 m/s indicate sarcopenia)

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): Comprehensive functional assessment

Timed Up and Go test: Evaluates mobility and fall risk

Assessing Frailty

Beyond the Fried criteria, several additional tools assess frailty:

Clinical Frailty Scale: A 9-point scale based on clinical description and functional status. Frailty Index: Calculates the proportion of accumulated deficits across multiple domains. FRAIL Scale: A simple 5-item questionnaire (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, Loss of weight)

Blumer and Le (2025) advocate for routine frailty screening in all older adults, particularly those with chronic conditions like heart failure, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease, where sarcopenia and frailty are highly prevalent .

Treatment and Prevention: Breaking the Cycle

The encouraging news? Both sarcopenia and frailty are treatable and preventable conditions. Multiple interventions have proven effective, especially when implemented early.

Exercise: The Most Powerful Intervention

Resistance training stands out as the single most effective intervention for sarcopenia. Sato et al. (2024) review extensive evidence showing that progressive resistance exercise:

Increases muscle mass and strength even in very old adults

Improves mitochondrial function and biogenesis

Reduces chronic inflammation and oxidative stress

Enhances insulin sensitivity and metabolic health

Improves balance and reduces fall risk

Optimal programs typically involve 2-3 sessions weekly, targeting major muscle groups with exercises progressed to maintain challenge

Aerobic exercise complements resistance training by:

Improving cardiovascular fitness

Enhancing mitochondrial capacity

Supporting weight management

Reducing inflammation

Improving mood and cognitive function

Combined exercise programs addressing both resistance and aerobic fitness provide the greatest benefits for combating sarcopenia and frailty

Nutrition: Fueling Recovery

Protein intake requires special attention. Viña and Gomez-Cabrera (2025) recommend older adults consume 1.0-1.2 g protein per kg body weight daily, with even higher intakes (1.2-1.5 g/kg) for those with sarcopenia or during illness. Distributing protein across meals (25-30g per meal) optimizes muscle protein synthesis (Viña & Gomez-Cabrera, 2025).

Essential amino acids, particularly leucine, play crucial roles in stimulating muscle protein synthesis. Supplementation may benefit those unable to meet needs through diet alone

Vitamin D deficiency is common in older adults and associated with both sarcopenia and frailty. Supplementation (800-2000 IU daily) may improve muscle strength and function, particularly in deficient individuals .

Omega-3 fatty acids show promise for reducing inflammation and supporting muscle health, though more research is needed to establish optimal dosing .

Pharmacological Approaches

While exercise and nutrition remain foundational, several medications show promise:

Testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men can increase muscle mass and strength, though cardiovascular risks require careful consideration (Sato et al., 2024).

Selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) are being investigated as potentially safer alternatives to testosterone, though none are currently approved for sarcopenia (Sato et al., 2024).

Myostatin inhibitors block this negative regulator of muscle growth and are under active investigation in clinical trials (Sato et al., 2024).

Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants like MitoQ show early promise for improving mitochondrial function and reducing oxidative stress in aging muscle (Sato et al., 2024).

Managing Sarcopenia in Heart Failure

For sarcopenic heart failure patients, Dodds and Sayer (2016) recommend tailored approaches:

Cardiac rehabilitation programs should be adapted for patients with sarcopenia, incorporating progressive resistance training alongside traditional aerobic exercise (Dodds & Sayer, 2016).

Nutritional optimization is critical, as heart failure patients often have poor appetite and increased metabolic demands. Protein supplementation and addressing micronutrient deficiencies can support muscle maintenance (Dodds & Sayer, 2016).

Medication review should identify drugs that may contribute to muscle loss, including some beta-blockers and diuretics that may need adjustment (Dodds & Sayer, 2016).

Multidisciplinary care involving cardiologists, geriatricians, physiotherapists, and dietitians provides comprehensive management addressing both cardiac and musculoskeletal health (Dodds & Sayer, 2016).

The Future of Frailty and Sarcopenia Management

Research continues to advance our understanding and treatment options. Álvarez-Bustos et al. (2022) emphasize that their population study demonstrates the preventable nature of frailty transitions, suggesting that targeting sarcopenia could dramatically reduce frailty prevalence at the population level.

Emerging areas of investigation include:

Senolytic therapies that selectively eliminate senescent cells contributing to inflammation and muscle aging Gene therapy approaches targeting specific pathways in muscle metabolism and mitochondrial function Personalized medicine using genetic and biomarker profiles to tailor interventions Artificial intelligence for early detection and monitoring of sarcopenia and frailty progression Novel exercise modalities including blood flow restriction training and neuromuscular electrical stimulation for those unable to perform traditional resistance training

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can you reverse sarcopenia once it develops?

A: Yes! While sarcopenia becomes more challenging to reverse with advanced age, research consistently shows that resistance training combined with adequate protein intake can increase muscle mass and strength even in very old adults. The key is starting intervention as early as possible and maintaining consistency.

Q: How much protein do older adults really need?

A: Current evidence suggests older adults need 1.0-1.2 g of protein per kg body weight daily for maintenance, with higher intakes (1.2-1.5 g/kg) recommended for those with sarcopenia or during illness. Distributing protein across meals (25-30g per meal) optimizes muscle protein synthesis.

Q: Is frailty the same as sarcopenia?

A: No, though they're closely related. Sarcopenia specifically refers to muscle loss, while frailty is a broader syndrome encompassing physical, cognitive, and social vulnerability. Sarcopenia is a major contributor to physical frailty, but you can have one without the other.

Q: How is sarcopenia diagnosed?

A: Diagnosis requires assessing three components: muscle mass (via DXA, BIA, or imaging), muscle strength (grip strength or chair stand test), and physical performance (gait speed or SPPB). Meeting criteria in all three domains confirms sarcopenia.

Q: What's the best exercise for preventing sarcopenia?

A: Resistance training targeting major muscle groups 2-3 times weekly is most effective for maintaining muscle mass and strength. Combined with aerobic exercise, this provides optimal benefits for preventing both sarcopenia and frailty.

Q: Why do heart failure patients develop sarcopenia?

A: Heart failure promotes muscle wasting through reduced cardiac output limiting nutrient delivery, chronic inflammation, neurohormonal activation promoting muscle breakdown, and reduced physical activity due to symptoms like fatigue and shortness of breath.

Q: Can supplements help with sarcopenia?

A: Some supplements show promise, particularly protein and essential amino acids, vitamin D in deficient individuals, and omega-3 fatty acids. However, supplements should complement rather than replace exercise and whole-food nutrition.

Q: At what age should I worry about sarcopenia?

A: Muscle loss typically begins around age 40, accelerating after 60. However, prevention should start earlier—maintaining muscle through regular resistance training and adequate protein throughout adulthood provides the best protection.

Q: How does mitochondrial dysfunction contribute to sarcopenia?

A: Mitochondria produce the energy muscles need to function. Age-related mitochondrial dysfunction reduces energy production, increases oxidative stress, and impairs muscle repair—all contributing to sarcopenic decline. Exercise improves mitochondrial function, partially explaining its effectiveness.

Q: Is frailty reversible?

A: Yes, particularly in earlier stages. Research shows that comprehensive interventions addressing exercise, nutrition, medication review, and social engagement can help individuals transition from frail to pre-frail or even robust states. Early identification and intervention offer the best outcomes.

Take Action: Protect Your Future Independence

Understanding sarcopenia and frailty is the first step—but knowledge without action won't preserve your independence and quality of life. Whether you're concerned about your own health or that of a loved one, the time to act is now.

Start today with these evidence-based steps:

Schedule a frailty assessment with your healthcare provider, especially if you've noticed declining strength or endurance

Begin resistance training—even simple bodyweight exercises or light weights can make a significant difference

Evaluate your protein intake and aim for 25-30g of protein at each meal

Get your vitamin D levels checked and supplement if deficient

If you have heart failure, ask your cardiologist about screening for sarcopenia and cardiac rehabilitation programs

Stay physically active—both resistance and aerobic exercise protect against sarcopenia and frailty

Prioritize quality sleep, as this is when muscle repair and recovery occur

Remember, the frailty cycle can be broken. Sarcopenia is preventable and treatable. The research is clear: early intervention works. Don't wait until severe decline occurs—protect your independence by taking action today.

Share this article with friends and family who might benefit from understanding these crucial health concepts. Consider joining our community for regular updates on aging, muscle health, and evidence-based strategies for maintaining independence and vitality throughout life.

Your future self will thank you for the steps you take today to preserve muscle, maintain mitochondrial health, and break the frailty cycle before it begins.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

.Related Articles

Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia: The Critical Connection | DR T S DIDWAL

Hormone Therapy and Sarcopenia: Testosterone, HGH, and Muscle Mass | DR T S DIDWAL

Sarcopenia Treatment Options: Medical and Lifestyle Interventions That Actually Work | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Prevent Sarcopenia: Fight Age-Related Muscle Loss and Stay Strong | DR T S DIDWAL

Who Gets Sarcopenia? Key Risk Factors & High-Risk Groups Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Exercises for Sarcopenia: Strength Training Guide for Older Adults | DR T S DIDWAL

Best Supplements for Sarcopenia: Vitamin D, Creatine, and HMB Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Álvarez-Bustos, A., Carnicero-Carreño, J. A., Davies, B., Garcia-Garcia, F. J., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F., Rodríguez-Mañas, L., & Alonso-Bouzón, C. (2022). Role of sarcopenia in the frailty transitions in older adults: a population-based cohort study. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 13(5), 2352–2360. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13055

Blumer, J., & Le, B. (2025). Rethinking sarcopenia and frailty of the elderly. Post Reproductive Health, 31(3), 184–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/20533691251337173

Dodds, R., & Sayer, A. A. (2015). Sarcopenia and frailty: new challenges for clinical practice. Clinical medicine (London, England), 15 Suppl 6, s88–s91. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.15-6-s88

.Sato, R., Vatic, M., Da Fonseca, G. W. P., Anker, S. D., & Von Haehling, S. (2024). Biological basis and treatment of frailty and sarcopenia. Cardiovascular Research, 120(9), 982–998. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvae073

Viña, J., & Gomez-Cabrera, M. C. (2025). Molecular mechanism involved in sarcopenia and frailty, diagnosis and therapy. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 105, 101387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2025.101387