Cardiovascular Aging and Heart Failure: Can We Slow the Biological Clock of the Heart?

Discover how cardiovascular aging—driven by chronic inflammation, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction—leads to heart failure. Learn the science and prevention strategies.

AGINGHEART

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/11/202614 min read

The human heart beats nearly 100,000 times a day—over 35 million times a year—without rest. By the age of 70, it has contracted more than 2.5 billion times. Yet despite this remarkable endurance, the heart is not immune to time. Cardiovascular aging is not merely the passage of years; it is a progressive biological transformation that reshapes the structure, metabolism, and function of both the heart and blood vessels. Emerging evidence suggests that aging itself—independent of hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease—can directly drive the development of heart failure (Goyal et al., 2024).

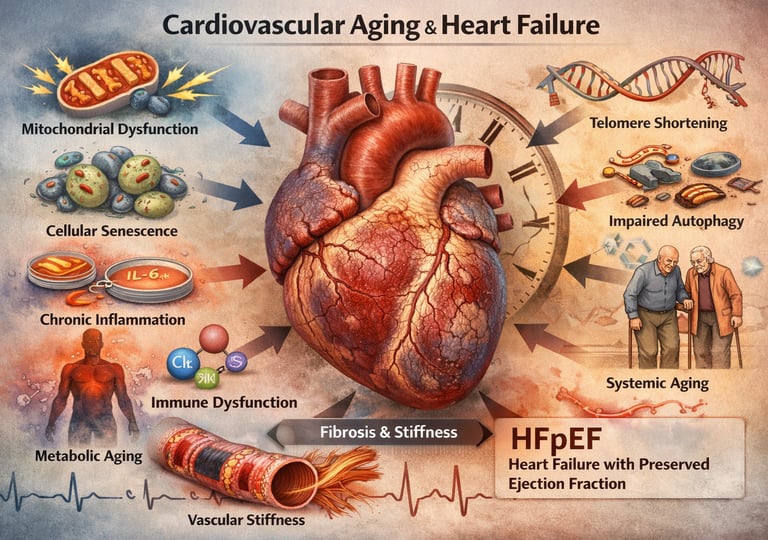

At the center of this transformation lies a convergence of molecular stressors: mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic low-grade inflammation (“inflammaging”), oxidative injury, cellular senescence, and impaired autophagy (Zhao et al., 2025). These processes gradually stiffen the myocardium, promote interstitial fibrosis, and impair diastolic relaxation—key features of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), now the dominant form of heart failure in older adults (Triposkiadis et al., 2019). Importantly, cardiovascular aging does not occur in isolation. Systemic aging—affecting immune, metabolic, endocrine, and vascular systems—creates a pro-inflammatory milieu that accelerates myocardial remodeling and vulnerability to decompensation (Fang et al., 2025).

Understanding cardiovascular aging reframes heart failure not simply as a disease of blocked arteries or weakened pumps, but as a manifestation of accumulated biological stress across decades. As global populations age, deciphering this connection is no longer theoretical—it is central to preventing the next epidemic of age-related heart failure.

Clinical Pearls

1. HFpEF is the Face of Cardiovascular Aging

The primary manifestation of pure, age-related cardiac remodeling is Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF).

Pearl: When evaluating an older adult for heart failure, recognize that diastolic dysfunction (impaired relaxation due to stiffness/fibrosis) is the hallmark, driven by cellular senescence and chronic inflammation, rather than just systolic dysfunction (weakened pump). The normal ejection fraction (>50%) does not rule out severe, age-related heart failure.

Prioritize assessment of left ventricular filling pressures and diastolic function (e.g., using echocardiography parameters like E/e' ratio) in patients with unexplained shortness of breath or fatigue, even with preserved EF.

2. Systemic Senescence Drives Cardiac Fibrosis

Cardiovascular aging is a systemic disease; the heart doesn't age in isolation.

Pearl: The accumulation of senescent cells (the "cellular zombies") throughout the body—not just in the heart—releases the harmful Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). This cocktail of inflammatory cytokines (like IL-6 and TNF-alpha) acts remotely to stimulate cardiac fibroblasts to become scar-forming myofibroblasts, leading directly to the stiffening and fibrosis characteristic of HFpEF.

Future therapies may involve senolytics (drugs that clear senescent cells). For now, interventions that globally reduce systemic inflammation (e.g., healthy diet, exercise) are critical anti-aging strategies.

3. Mitochondrial Dysfunction is the Energy Crisis of the Aging Heart

The aging heart suffers from a progressive energy crisis that severely limits its ability to cope with stress.

Pearl: Age-related mitochondrial dysfunction reduces the heart's energy (ATP) supply and simultaneously generates excessive Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), creating a vicious cycle of oxidative stress and damage in highly metabolic cardiomyocytes. This lack of energetic reserve is why older hearts are disproportionately susceptible to decompensation from minor stressors like infection or mild hypertension.

Encourage regular aerobic exercise, which is one of the most powerful non-pharmacological methods to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis and improve mitochondrial quality control (autophagy) in the heart.

4. Vascular Stiffness Dictates Cardiac Workload

Aging of the blood vessels is as critical as aging of the heart muscle itself.

Pearl: Progressive loss of elasticity (stiffening) in large arteries (e.g., the aorta) increases pulsatile load and afterload, forcing the already stiffening left ventricle to pump against greater resistance. This sustained pressure overload accelerates the age-related left ventricular hypertrophy and stiffening, compounding the risk for heart failure.

Aggressive but careful management of hypertension is essential. Reducing vascular stiffness by targeting blood pressure and endothelial dysfunction offers dual protection for both the vessels and the heart muscle.

5. Targeting Aging Mechanisms Offers Novel Therapeutic Avenues

Traditional heart failure drugs manage symptoms; emerging science targets the fundamental aging processes themselves.

Pearl: The mechanisms of cardiovascular aging (senescence, inflammaging, mitochondrial failure) are becoming viable drug targets. Established drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors, increasingly used for heart failure, may exert some of their profound benefits through "pleiotropic" effects, potentially improving mitochondrial function and reducing inflammation independent of their initial glycemic actions.

Stay informed about clinical trials for agents like senolytics, autophagy enhancers, and targeted anti-inflammatory drugs. These represent the next generation of therapies focused on modifying the underlying biological clock of the heart.

What Is Cardiovascular Aging?

Before we dive into how aging contributes to heart failure, let's clarify what we mean by cardiovascular aging. This isn't simply about the passage of time. Rather, it's a distinct biological process involving progressive deterioration of heart and blood vessel function at the cellular and molecular levels.

Cardiovascular aging encompasses several interconnected changes:

The heart muscle itself undergoes alterations in both structure and function. The walls of the left ventricle—the chamber responsible for pumping blood to your entire body—can become thicker and stiffer, a condition called left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction (Triposkiadis et al., 2019). Meanwhile, blood vessels lose elasticity, becoming stiffer and less responsive to the body's needs. The inner lining of blood vessels, called the endothelium, becomes dysfunctional, compromising its role in regulating blood flow and pressure.

Perhaps most critically, the cells of the heart and blood vessels accumulate damage at the molecular level. Mitochondria, the energy-producing structures within cells, become less efficient. Oxidative stress increases, meaning the body produces more harmful free radicals that damage cellular components. Inflammation becomes chronic, with inflammatory molecules continuously circulating throughout the cardiovascular system (Zhao et al., 2025). Additionally, cellular senescence—the process where cells stop dividing but don't die and continue to release harmful substances—contributes to this inflammatory state.

These changes happen gradually and can be difficult to detect until they've progressed significantly. But understanding them is crucial because they create the perfect environment for heart failure to develop.

Understanding Heart Failure in the Context of Aging

Heart failure occurs when the heart can't pump enough blood to meet the body's needs or can't relax properly to fill with blood. There are several types, but two are particularly relevant to cardiovascular aging: systolic heart failure, where the heart's pumping function is weakened, and diastolic heart failure (also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction), where the heart becomes stiff and doesn't relax properly.

Interestingly, the aging process seems to preferentially lead to diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)—a type of heart failure that's increasingly common in older adults. This occurs because age-related stiffening of the heart muscle impairs the organ's ability to relax and fill with blood between heartbeats.

What makes this particularly important is that age-related heart failure presents unique challenges. Older patients may have other medical conditions complicating the picture. They may be on multiple medications that interact with heart failure treatments. And the symptoms of heart failure can overlap with other age-related conditions, making diagnosis trickier. Additionally, aging of the heart isn't simply about the organ itself—systemic changes throughout the body, including in the immune system, metabolic function, and other systems, all contribute to heart disease progression.

The Molecular Mechanisms: How Aging Damages the Heart at the Cellular Level

The bridge between normal aging and heart failure exists at the molecular level. Let's explore the key mechanisms that researchers have identified:

One of the hallmark features of cardiovascular aging is increased oxidative stress. As we age, mitochondria become less efficient at producing energy while simultaneously generating more reactive oxygen species (ROS)—harmful free radicals that damage DNA, proteins, and lipids. This creates a vicious cycle: damaged mitochondria produce even more free radicals, leading to further damage.

In the heart, this matters tremendously because cardiac muscle cells require enormous amounts of energy to function. When mitochondrial dysfunction reduces energy production and increases oxidative stress, cardiac cell deterioration accelerates. The heart's ability to respond to stress diminishes, making it vulnerable to conditions that would be manageable in younger individuals.

Chronic Inflammation and Inflammaging

Another crucial mechanism is inflammaging—chronic, low-grade inflammation that develops with age. While acute inflammation is a healthy immune response to injury or infection, chronic inflammation is different. It's a persistent state where inflammatory molecules like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) continuously circulate throughout the body.

In the cardiovascular system, chronic inflammation accelerates vascular aging and cardiac remodeling. It promotes endothelial dysfunction, reducing the body's ability to regulate blood flow and maintain healthy blood pressure. Additionally, inflammation stimulates the transformation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, leading to excessive fibrosis (scar tissue formation) in the heart (Fang et al., 2025). This fibrosis directly contributes to left ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction, two hallmarks of age-related heart failure.

Cellular Senescence and Senescent Cells

Cellular senescence is a state where cells lose their ability to divide but don't die. Instead, they enter a kind of cellular zombie state, where they remain metabolically active but release harmful substances called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

As people age, senescent cells accumulate throughout the body, including in the heart and blood vessels. These cells secrete inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases that damage surrounding tissues and promote vascular dysfunction, fibrosis, and myocardial stiffness. Interestingly, removing these senescent cells in animal models has shown promise in reversing some age-related cardiovascular dysfunction, suggesting they're a promising therapeutic target.

Telomere Shortening and Genomic Instability

Telomeres are protective caps on the ends of chromosomes that shorten with each cell division. As telomeres shorten, cells eventually enter senescence or apoptosis (programmed death). Telomere shortening is considered a fundamental aging mechanism, and it's accelerated by oxidative stress and inflammation.

In the cardiovascular system, telomere shortening correlates with vascular dysfunction and increased cardiovascular disease risk. Cells with critically short telomeres can't divide to replace damaged cells, leading to progressive tissue deterioration.

Impaired Autophagy and Protein Quality Control

Autophagy is the cell's housekeeping system—it digests and recycles damaged organelles and proteins. With age, autophagy becomes less efficient, leading to accumulation of damaged mitochondria and misfolded proteins. This impairment is particularly problematic in cardiac cells, which have limited capacity for cell division and thus depend on efficient protein quality control.

When protein quality control fails, misfolded proteins aggregate, forming toxic deposits that interfere with normal cellular function and promote cardiomyocyte death and dysfunction.

Key Research Findings: What Recent Studies Tell Us

Study 1: Aging in Heart Failure (Goyal, Maurer, & Roh, 2024)

Recent comprehensive research has provided crucial insights into how aging mechanisms specifically contribute to heart failure development. This study emphasizes that cardiovascular aging represents a distinct biological process that operates independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The research highlights that even without hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease, the aging process alone can lead to structural remodeling of the heart, particularly involving left ventricular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction.

A key takeaway is the recognition that age-related heart failure often manifests as HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction), which is increasingly prevalent in older adults. The study identifies cellular senescence, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation as central drivers of this age-associated cardiac remodeling. Understanding these mechanisms opens new avenues for intervention targeting the aging process itself rather than just treating heart failure symptoms.

Study 2: Cardiovascular Aging and Heart Failure (Triposkiadis, Xanthopoulos, & Butler, 2019)

This review provided foundational understanding of how vascular aging and cardiac aging interact to promote heart failure development. The research demonstrates that endothelial dysfunction, progressive arterial stiffness, and impaired vasodilation are characteristic features of cardiovascular aging that precede and predispose to heart failure.

The study emphasizes that myocardial aging involves both structural changes (like increased collagen deposition and fibrosis) and functional changes (reduced contractile reserve and diastolic relaxation impairment). A critical insight is that systemic vascular aging contributes to increased afterload (the resistance the heart must pump against), which places additional stress on an aging heart. The interaction between aging blood vessels and an aging heart creates a compound problem: stiffer vessels force the heart to work harder while the heart becomes less capable of meeting this demand.

Study 3: Mechanisms of Aging in the Cardiovascular System (Zhao et al., 2025)

This recent comprehensive review provides detailed examination of molecular mechanisms underlying cardiovascular aging, with particular emphasis on the role of immune system dysregulation. The research highlights how aging alters immune function, promoting chronic inflammation while simultaneously reducing the immune system's capacity to clear damaged cells and pathogens.

Key mechanisms identified include inflammaging, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, and autophagy impairment. The study emphasizes that these mechanisms are interconnected—damage in one pathway exacerbates damage in others. For instance, mitochondrial dysfunction increases oxidative stress, which accelerates cellular senescence. Senescent cells then secrete inflammatory molecules that promote further mitochondrial dysfunction. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle of damage.

The research identifies several promising therapeutic targets: senolytic drugs (which specifically kill senescent cells), antioxidants, anti-inflammatory agents, and therapies that enhance autophagy. The challenge ahead is translating these laboratory findings into effective clinical treatments for age-related heart failure.

Study 4: Systemic Aging Fuels Heart Failure (Fang et al., 2025)

Perhaps most intriguingly, recent research emphasizes that cardiovascular aging and heart failure development aren't solely consequences of aging within the heart itself—instead, systemic aging throughout the body contributes significantly. This study provides a systems-level perspective on aging-related heart disease.

The research details how immune system aging, changes in metabolic function, hormonal dysregulation, and alterations in the autonomic nervous system all contribute to cardiac aging and heart failure susceptibility. For example, immune senescence (aging of immune cells) promotes a shift toward pro-inflammatory immune responses while reducing the capacity to fight infection and clear damaged cells. Metabolic aging reduces insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function throughout the body, affecting the heart's energy metabolism. Hormonal changes with age alter how the cardiovascular system responds to stress.

This systemic perspective is important because it suggests that interventions extending beyond the heart—such as exercises promoting overall health, metabolic optimization, and management of systemic inflammation—might all contribute to preserving cardiac function with age. The study identifies molecular pathways connecting systemic aging to cardiac disease, suggesting that therapies targeting fundamental aging processes could simultaneously reduce heart failure risk.

Why Older Adults Are Particularly Vulnerable: The Perfect Storm

Understanding cardiovascular aging explains why heart failure becomes increasingly common with age. It's not just that older people have more time to develop disease—it's that aging of the cardiovascular system creates a unique vulnerability.

Consider the interplay of factors: Myocardial stiffness develops due to fibrosis and cellular senescence (Goyal et al., 2024). Meanwhile, vascular stiffness increases, raising the resistance the heart must work against. Mitochondrial dysfunction reduces the heart's energy supply right when it needs more energy. Chronic inflammation promotes further damage while the immune system becomes less capable of managing the situation. Oxidative stress accumulates, damaging proteins and DNA in cardiac cells. The result is a heart that's structurally compromised, functionally impaired, and increasingly susceptible to decompensation when stressed by other conditions like infection, new medications, or increased physical demands.

This explains why older adults with heart failure often have worse outcomes, require more hospitalizations, and struggle more with recovery. Their hearts aren't just dealing with disease—they're dealing with disease layered on top of age-related dysfunction.

The Missing Link: How Systemic Aging Contributes to Cardiac Aging

Recent research highlights an often-overlooked aspect of heart failure in older adults: it's not just about heart aging. Systemic aging drives cardiac aging. This represents a paradigm shift in how we understand age-related heart disease.

The gut microbiome changes with age, shifting toward a pro-inflammatory composition that promotes intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation. The gut-heart axis means these changes directly impact cardiac health. Immunosenescence (aging of the immune system) shifts immune responses from adaptive (targeted) responses to innate (generalized) responses, promoting chronic inflammation. Metabolic syndrome becomes more prevalent with age, with insulin resistance and altered lipid metabolism accelerating cardiovascular disease. Neurohormonal dysregulation affects how the autonomic nervous system controls heart rate and blood pressure. Hormonal changes, including declining estrogen in women and altered testosterone signaling in men, affect cardiovascular function.

Each of these systemic changes independently stresses the cardiovascular system. Combined, they create an environment where heart failure development becomes nearly inevitable without intervention.

Practical Implications: What This Means for Prevention and Management

Understanding the mechanisms of cardiovascular aging and heart failure development has real-world implications for prevention and treatment.

Prevention strategies should target the fundamental aging processes. Regular aerobic exercise improves mitochondrial function, reduces oxidative stress, and promotes metabolic health. Resistance training helps preserve muscle mass and function. Mediterranean-style diets are anti-inflammatory and reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Cognitive and social engagement supports brain health, which influences cardiovascular function through the autonomic nervous system. Stress management through meditation or similar practices reduces inflammation. Quality sleep is essential for cellular repair and metabolic health.

For those already developing heart failure, understanding these mechanisms informs treatment approaches. ACE inhibitors and ARBs don't just lower blood pressure—they reduce inflammation and may slow cardiac remodeling. Beta-blockers reduce oxidative stress and improve mitochondrial function. SGLT2 inhibitors, increasingly used in heart failure, may have anti-aging properties. Emerging therapies like senolytics (drugs that eliminate senescent cells) show promise in animal models of age-related heart disease and may eventually offer new treatment options.

FAQ: Common Questions About Cardiovascular Aging and Heart Failure

Q: Can you prevent cardiovascular aging? A: While you can't stop aging entirely, you can significantly slow cardiovascular aging. Lifestyle interventions—particularly regular exercise, healthy diet, stress management, and quality sleep—meaningfully reduce the rate of cardiovascular deterioration. Some medications may also slow aging-related cardiac changes.

Q: Is heart failure in older adults always related to aging? A: Not entirely. Other factors like hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease remain important. However, even after accounting for these factors, cardiovascular aging contributes substantially to heart failure risk in older adults. The combination of aging plus other risk factors creates particularly high risk.

Q: Are there new treatments targeting the aging process itself? A: Yes, research is exploring treatments targeting mechanisms of aging. Senolytics (senescent cell-eliminating drugs) are in clinical trials. Other approaches under investigation include enhanced autophagy, mitochondrial function improvement, and anti-inflammatory interventions.

Q: Why does heart failure with preserved ejection fraction become more common with age? A: HFpEF develops when the heart becomes stiff and can't relax properly—exactly what happens with cardiovascular aging. Age-related fibrosis, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction all promote this stiffening, making HFpEF the predominant form of age-related heart failure.

Q: Can weight loss or exercise help if you already have age-related heart failure? A: Absolutely. Even modest weight loss and gentle exercise programs tailored to individual capacity improve outcomes in age-related heart failure. Exercise stimulates beneficial adaptations in the heart and improves mitochondrial function.

Key Takeaways

Understanding cardiovascular aging and its role in heart failure development provides actionable insights:

Cardiovascular aging is a distinct biological process involving molecular damage at the cellular level, not simply the passage of time

Oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, cellular senescence, and mitochondrial dysfunction drive age-related cardiac changes

Systemic aging throughout the body contributes to cardiac aging, suggesting that overall health interventions support heart health

Age-related heart failure predominantly manifests as HFpEF, with increasing prevalence in older populations

Prevention strategies targeting aging mechanisms—including exercise, diet, stress management, and sleep—can meaningfully slow cardiovascular aging

Emerging therapies targeting aging mechanisms offer promise for future heart failure treatment

Early recognition and management of age-related cardiovascular changes can prevent or delay heart failure development

Author’s Note

The science of cardiovascular aging represents one of the most rapidly evolving frontiers in modern cardiology. For decades, heart failure was viewed primarily through the lens of traditional risk factors—hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and valvular disorders. While these remain critical contributors, emerging evidence increasingly demonstrates that aging itself is an independent and biologically active driver of myocardial remodeling and heart failure development. This article was written to synthesize current mechanistic insights into oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, inflammaging, and systemic metabolic decline—processes that collectively reshape the aging heart.

Importantly, the goal is not to portray aging as pathology, but to distinguish between chronological aging and modifiable biological aging. Many of the molecular pathways described—impaired autophagy, vascular stiffening, low-grade inflammation—are influenced by lifestyle, environmental exposures, and emerging therapeutics. As such, cardiovascular aging is neither inevitable nor entirely irreversible. Preventive cardiology must increasingly integrate geroscience principles into clinical practice.

The references cited reflect contemporary reviews and translational research shaping our current understanding of age-related heart failure, particularly HFpEF. While ongoing trials are exploring senolytics, mitochondrial-targeted therapies, and anti-inflammatory interventions, many findings remain investigational. Readers are encouraged to interpret emerging therapies with scientific caution while embracing well-established interventions such as exercise, metabolic optimization, and blood pressure control.

As global populations age, bridging gerontology and cardiology will be essential. Understanding the biology of aging is no longer academic—it is central to preventing the next wave of heart failure.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Can Modest Weight Loss Prevent Heart Disease? What the Latest Research Reveals | DR T S DIDWAL

Statins, Side Effects, and the Placebo Problem: What Recent Research Really Shows | DR T S DIDWAL

The Cholesterol Paradox: When Lower Numbers Don’t Mean Lower Heart Risk | DR T S DIDWAL

hsCRP in Cardiovascular Disease: Should It Be Measured for Risk Assessment in 2026? | DR T S DIDWAL

Your Body Fat Is an Endocrine Organ—And Its Hormones Shape Your Heart Health | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Fang, Z., Raza, U., Song, J., Lu, J., Yao, S., Liu, X., Zhang, W., & Li, S. (2025). Systemic aging fuels heart failure: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic avenues. ESC Heart Failure, 12(2), 1059–1080. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14947

Goyal, P., Maurer, M. S., & Roh, J. (2024). Aging in heart failure. JACC Heart Failure, 12(5), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2024.02.021

Triposkiadis, F., Xanthopoulos, A., & Butler, J. (2019). Cardiovascular aging and heart failure: JACC review topic of the week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 74(6), 804–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.053

Zhao, X., Yang, X., Lin, Y., Lei, R., Ding, W., He, X., Cao, Y., Zhang, D., Liu, P., Liang, M., Han, Z., & Jiang, Y. (2025). Mechanisms of aging in the cardiovascular system: Challenges and opportunities. Frontiers in Immunology, 16, 1635736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1635736