Can Modest Weight Loss Prevent Heart Disease? What the Latest Research Reveals

Lose just 5–10% of your weight and significantly lower heart disease risk—discover the science behind small, powerful changes.

HEARTOBESITY

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/18/202615 min read

Cardiovascular disease remains the world’s leading cause of death — but one of its most powerful drivers is both measurable and treatable: excess body weight. The relationship between obesity and heart disease is no longer observational or speculative; it is mechanistic, outcome-driven, and supported by modern cardiovascular trials. What has changed dramatically between 2023 and 2026 is not the recognition of risk, but the availability of therapies that meaningfully reduce that risk.

Recent evidence confirms that weight loss is not merely cosmetic or metabolic — it is cardioprotective. An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found that structured weight management interventions significantly reduce major adverse cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality (Chen et al., 2025). The 2025 ACC expert consensus statement further formalized obesity treatment as a core component of cardiovascular care, particularly emphasizing GLP-1 receptor agonists with proven cardiovascular event reduction (Gilbert et al., 2025). Meanwhile, tailored global recommendations now highlight that patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes require condition-specific weight strategies rather than generic advice (Huang et al., 2025).

Yet the field faces a crucial reality: obesity is a chronic disease requiring sustained therapy. Discontinuation of pharmacologic treatment is associated with substantial weight regain within 12 months (West et al., 2026), reinforcing long-term management principles long advocated in preventive cardiology (Hritani et al., 2023).

The science is clear: effective weight management is now one of the most evidence-based strategies to reduce heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death in high-risk populations.

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death globally, and the connection between excess body weight and heart disease is no longer a matter of debate — it is one of the most well-documented relationships in modern medicine. Yet for many patients and clinicians alike, the question is no longer whether weight management matters for heart health, but how to do it effectively, safely, and sustainably.

A wave of landmark research published between 2023 and 2026 has dramatically reshaped how cardiologists, obesity specialists, and primary care physicians think about weight-related cardiovascular risk. From a fresh ACC expert consensus statement to a sweeping umbrella review of cardiovascular outcomes, and from tailored global recommendations to sobering data on weight regain after stopping medication — the landscape is evolving fast.

This post unpacks the most important insights from five key studies and guidelines, translating the science into actionable understanding for patients, healthcare providers, and anyone invested in the future of preventive cardiology.

Clinical pearls.

1. The "Dose-Response" of Weight Loss

There is a linear correlation between the percentage of total body weight loss (TBWL) and the reduction of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE). While 5% TBWL improves metabolic markers, 10–15% is often required to significantly alter the trajectory of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and atherosclerotic progression.

Every bit counts, but "more is better" for your heart. Losing the first 5% of your weight is like clearing the fog; losing 15% is like paving the road for a much smoother journey for your heart.

2. Obesity as a Primary Cardiometabolic Disease

Obesity is not merely a comorbid condition but a primary driver of systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Chronic adipose tissue expansion leads to "lipotoxicity," which directly damages cardiac myocytes.

Obesity isn’t just about the scale or how your clothes fit; it’s a chronic illness, much like high blood pressure. Your body’s fat cells are chemically active, and when there are too many, they send out "stress signals" that irritate your heart and blood vessels.

3. The "Legacy Effect" of Lifestyle Foundations

While GLP-1 receptor agonists provide potent weight reduction, the "weight-loss maintenance" phase is statistically more successful in patients who established intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) before and during pharmacotherapy.

Think of weight-loss medications like a high-performance engine and lifestyle habits (diet and exercise) like the steering wheel. The engine gets you moving fast, but without a solid steering wheel, you’ll likely lose control of your progress once the engine is turned off.

4. Precision Pharmacology: Not All Meds Fit All Hearts

Clinical selection of anti-obesity medications (AOMs) must be tailored to the specific cardiac phenotype. For instance, GLP-1s are preferred for atherosclerotic disease, while certain older sympathomimetic agents may be contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled arrhythmias or severe hypertension.

Weight loss medicine isn't "one size fits all." What worked for your neighbor might not be safe for your specific heart condition. Your cardiologist needs to pick the tool that protects your heart while shrinking your waistline.

5. The Reality of the "Relapse" (Weight Regain)

Scientific Tone: Weight regain following the cessation of incretin-based therapies is a physiological expectation, not a behavioral failure. The "set-point" theory suggests that the body aggressively defends its highest weight through hormonal adaptations (ghrelin/leptin shifts) once exogenous suppression by the medication is removed.

Patient Tone: If you stop your medication and the weight starts to come back, you didn't "fail." Your body is programmed to try to get back to its old weight. This is why we treat obesity as a long-term journey—just like we wouldn't stop taking asthma medicine just because we can breathe better today.

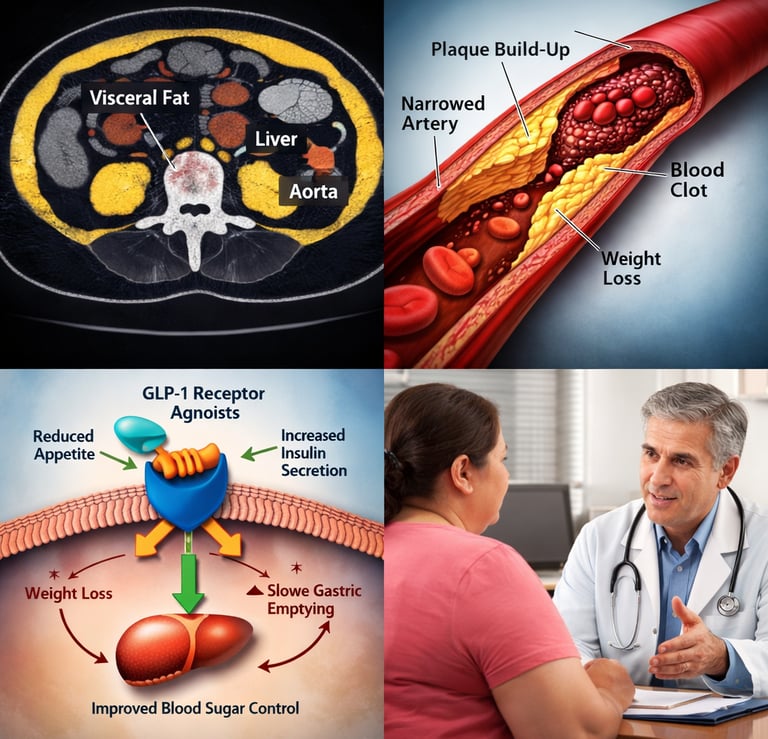

6. Focus on "Quality" over "Quantity" of Weight

The reduction of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and ectopic fat (fat stored in the liver or around the heart) is more cardioprotective than the reduction of subcutaneous fat. Sarcopenia (muscle loss) during rapid weight loss must be mitigated through resistance training to maintain basal metabolic rate.

Where you lose the fat matters more than how much the scale moves. We want to lose the "hidden fat" around your organs and heart, not the muscle in your legs. Keeping your muscles strong while losing weight is the secret to keeping your heart healthy and your metabolism running.

Next Steps: If you are currently on a weight management plan, you might want to ask your doctor: "How is my current plan specifically protecting my heart muscle and preventing muscle loss?"

Why Weight and Heart Disease Are Inseparable

The biology connecting obesity to cardiovascular disease is complex but well-mapped. Excess adipose tissue — especially visceral fat — drives chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and endothelial dysfunction. Together, these mechanisms form a perfect storm for atherosclerosis, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death.

Hritani et al. (2023) provided a foundational clinical overview of this relationship, emphasizing that obesity management is not merely a lifestyle preference but a core pillar of cardiovascular disease prevention. Their work highlights that even modest weight loss — in the range of 5–10% of body weight — can produce clinically meaningful improvements in blood pressure, glycemic control, lipid panels, and systemic inflammation. Importantly, they frame obesity not as a behavioral failure but as a chronic, multifactorial disease requiring structured, evidence-based medical management (Hritani et al., 2023).

This reframing matters enormously. When cardiovascular teams treat obesity as a disease rather than a personal shortcoming, patients receive earlier, more aggressive, and more compassionate care — which, as subsequent research confirms, translates directly into better cardiac outcomes.

The 2025 ACC Expert Consensus: A New Clinical Standard

Perhaps the most consequential development for practicing cardiologists and their patients in 2025 was the release of the American College of Cardiology's expert consensus statement on medical weight management for cardiovascular health optimization.

Gilbert et al. (2025) authored this comprehensive guidance through the ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, synthesizing current evidence across lifestyle, pharmacological, and procedural weight loss approaches specifically through the lens of cardiovascular risk reduction. The document provides practical, stepwise guidance for clinicians — particularly cardiologists — who may not have traditionally considered obesity management within their scope of practice but who are now squarely confronted with it given the explosion in effective pharmacotherapy options.

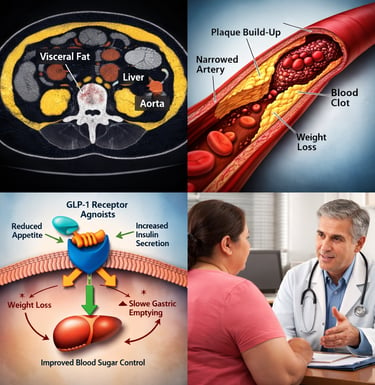

Several themes emerge from this document as particularly significant. First, the statement reinforces that cardiometabolic risk reduction — not a specific number on a scale — should be the primary treatment goal. Weight loss is valuable as a mechanism for improving blood pressure, lipids, blood glucose, and inflammatory markers, not as an end in itself. Second, the guidance addresses the growing class of GLP-1 receptor agonists, including semaglutide and tirzepatide, acknowledging that these agents have demonstrated cardiovascular event reduction in landmark trials independent of glycemic effects. Third, the document advocates for a multidisciplinary approach, encouraging cardiologists to partner with obesity medicine specialists, dietitians, and behavioral health professionals rather than managing these patients in isolation (Gilbert et al., 2025).

For patients, this statement signals something important: if your cardiologist has not yet discussed your weight as a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor — or if you have not been offered modern pharmacological options — it may be time to revisit that conversation. The standard of care has meaningfully advanced.

Do Weight Loss Interventions Actually Improve Cardiovascular Outcomes? The Evidence Is Strong

One of the persistent debates in medicine has been whether losing weight merely improves surrogate markers — like blood pressure and cholesterol — or whether it actually reduces hard cardiovascular events like heart attacks and strokes. Chen et al. (2025) tackled this question head-on in an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, covering a broad spectrum of weight control interventions.

The findings are compelling. Across the literature, weight loss interventions — spanning lifestyle programs, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery — were consistently associated with significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. Bariatric surgery showed some of the strongest and most durable effects, but pharmacological approaches (particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists) also demonstrated meaningful outcome reductions in high-risk populations. Lifestyle interventions, while generally producing more modest weight loss, showed consistent benefits for blood pressure, glycemic control, and metabolic markers — and when maintained, contributed to long-term cardiovascular risk reduction (Chen et al., 2025).

Importantly, the umbrella review also identified a dose-response relationship: greater and more sustained weight loss was generally associated with greater cardiovascular benefit. This finding has significant implications for treatment targets. It argues against accepting minimal or plateaued weight loss as "good enough" when more aggressive and sustained treatment is achievable and safe.

The review also acknowledged heterogeneity across interventions and patient populations, cautioning that not all weight loss strategies are equal across different cardiovascular risk profiles. This sets the stage for the increasingly important concept of individualized, tailored care — which the next body of research addresses directly.

Tailored Recommendations for Patients With Cardiovascular-Metabolic Disease

Not all patients with obesity are the same. A person with obesity and stable coronary artery disease has different needs, risks, and treatment priorities than someone with obesity and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction — or someone managing atrial fibrillation, hypertension, or type 2 diabetes alongside their cardiac condition. The failure to account for this complexity has historically led to suboptimal care.

Huang et al. (2025), representing the International Obesity Society Working Group on Cardiometabolic Diseases, addressed this gap directly by publishing tailored weight management recommendations specifically designed for obesity patients with cardiovascular-metabolic comorbidities. Their work, published in The Innovation, draws on a global expert consensus and provides condition-specific guidance across a range of cardiometabolic presentations.

For patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, the emphasis falls on pharmacological interventions that have demonstrated direct event reduction — namely GLP-1 receptor agonists and, in selected patients, bariatric metabolic surgery. For heart failure patients, particularly those with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), weight loss is identified as a pivotal therapeutic target, as excess adiposity is now understood to be a central driver of the HFpEF phenotype. For patients with hypertension and metabolic syndrome, intensive lifestyle intervention combined with pharmacotherapy is recommended as a first-line strategy.

Critically, Huang et al. (2025) also flag that certain weight loss approaches carry specific risks in cardiovascular populations. Very low-calorie diets, for example, may precipitate arrhythmias or electrolyte disturbances in vulnerable patients. Some weight loss medications carry contraindications in the presence of certain cardiac conditions. The paper argues persuasively that blanket recommendations are insufficient — and that the intersection of obesity medicine and cardiology demands specialists who understand both fields deeply.

For clinicians reading this: this paper is a useful clinical reference. For patients: it reinforces the importance of ensuring that your weight management plan has been specifically reviewed in the context of your heart condition — and not just handed down as generic advice.

The Weight Regain Problem: What Happens When You Stop Medication?

Here is an inconvenient truth that the field has been grappling with openly: for most patients, weight loss achieved through pharmacotherapy is not maintained after the medication is discontinued. The biology of body weight regulation is powerful, and the mechanisms that drive weight regain — including increased appetite, reduced satiety hormone signaling, and metabolic adaptation — are well-established.

West et al. (2026) published the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on this specific question in the BMJ, analyzing the magnitude and trajectory of weight regain after cessation of anti-obesity medications. The findings are striking and sobering. Across multiple drug classes, patients who stopped weight loss medication regained a substantial proportion of their lost weight — with the majority of regain occurring within the first 12 months of discontinuation. For GLP-1 receptor agonists specifically, which have become the dominant pharmacological option, the weight regain pattern was particularly pronounced, with patients regaining much of the weight lost during treatment within one to two years of stopping the drug (West et al., 2026).

This evidence carries several important clinical and policy implications. First, it reinforces the disease model of obesity — just as a patient does not expect to stop their antihypertensive medication and maintain normalized blood pressure indefinitely, we should not expect cessation of anti-obesity medication to maintain weight loss. Obesity is a chronic condition requiring chronic treatment in many patients. Second, it raises difficult questions about access, cost, and long-term prescribing. GLP-1 receptor agonists remain expensive, and insurance coverage is inconsistent — meaning many patients face forced discontinuation due to financial rather than clinical reasons. Third, it underscores the importance of behavioral and dietary foundations: patients who had more robust lifestyle changes in place during pharmacotherapy showed somewhat better retention of weight loss after stopping, though still experienced meaningful regain.

For cardiologists, this data means that the cardiovascular benefits of sustained weight loss — described above — cannot be assumed to persist after medication is stopped. Clinical management plans should account for long-term treatment sustainability from the outset.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How much weight do I need to lose to see cardiovascular benefits?

You do not need to reach an "ideal" body weight to protect your heart. Research consistently shows that losing as little as 5–10% of your total body weight produces clinically meaningful improvements in blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, and inflammation — all of which directly reduce cardiovascular risk. Greater and more sustained weight loss generally yields greater benefit, but even modest, maintained reductions matter significantly for long-term heart health (Chen et al., 2025; Hritani et al., 2023).

FAQ 2: Are GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide safe for people with heart disease?

For many patients with established cardiovascular disease, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not just safe — they have demonstrated direct cardiovascular event reduction in major clinical trials, independent of their effects on blood sugar or weight alone. The 2025 ACC expert consensus statement specifically acknowledges this class of medications as a key tool in cardiac risk management. That said, every patient's situation is different, and your cardiologist or obesity medicine specialist should review your full clinical picture before prescribing (Gilbert et al., 2025).

FAQ 3: Will I regain weight if I stop taking weight loss medication?

The evidence strongly suggests yes — for most people. A 2026 systematic review and meta-analysis published in the BMJ found that patients who discontinued anti-obesity medications, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, regained a substantial proportion of their lost weight, often within the first year after stopping. This reflects the chronic nature of obesity as a disease. Just as stopping blood pressure medication typically causes blood pressure to rise again, stopping weight management medication often triggers weight regain. Long-term treatment planning is essential (West et al., 2026).

FAQ 4: Does my type of heart condition affect which weight loss approach is right for me?

Absolutely, and this is one of the most important points in recent clinical literature. A patient with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has very different treatment priorities than someone with stable coronary artery disease or atrial fibrillation. Some weight loss strategies — including very low-calorie diets — carry specific risks in certain cardiac populations. The International Obesity Society's 2025 working group report emphasizes that weight management plans should be individually tailored to your cardiovascular-metabolic profile, not applied as one-size-fits-all advice (Huang et al., 2025).

FAQ 5: Should my cardiologist be involved in my weight management, or is that my primary care doctor's responsibility?

Increasingly, the answer is both — and the expectation that cardiologists should actively engage in obesity management is now embedded in formal clinical guidance. The 2025 ACC expert consensus statement was written specifically to equip cardiovascular specialists with the tools to address weight as a modifiable cardiac risk factor within their own practice, rather than simply referring patients away. If your cardiologist has not discussed your weight or offered evidence-based treatment options, it is entirely appropriate to raise the topic yourself (Gilbert et al., 2025).

FAQ 6: Is bariatric surgery a valid option for reducing cardiovascular risk?

Yes — for appropriately selected patients, bariatric metabolic surgery produces some of the most durable and substantial reductions in cardiovascular risk of any weight loss intervention currently available. The umbrella review by Chen et al. (2025) found that surgical approaches were consistently associated with significant reductions in major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality. Bariatric surgery is not appropriate for everyone, and eligibility criteria, surgical risk, and long-term follow-up requirements must be carefully considered in consultation with a multidisciplinary team that includes cardiology input (Chen et al., 2025; Huang et al., 2025).

Heart Disease Prevention and Weight Loss: Summary

1. Cardiovascular Disease Remains the Leading Global Killer

Heart disease continues to be the number one cause of death worldwide. Atherosclerosis, heart failure, stroke, and cardiometabolic disease are driven not only by cholesterol and blood pressure — but significantly by excess adiposity and metabolic dysfunction.

2. Obesity Is a Primary Cardiovascular Risk Factor

Excess body weight — particularly visceral fat — promotes:

Chronic systemic inflammation

Insulin resistance

Dyslipidemia (high triglycerides, low HDL)

Hypertension

Endothelial dysfunction

These mechanisms accelerate plaque formation, arterial stiffness, and cardiac remodeling.

3. Modest Weight Loss (5–10%) Produces Major Cardiovascular Benefits

Research consistently shows that losing just 5–10% of body weight leads to:

Meaningful reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure

Improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity

Lower triglycerides and improved lipid profiles

Reduced inflammatory markers

Importantly, benefits occur even before reaching “ideal” BMI targets.

4. Weight Loss Reduces Hard Cardiovascular Outcomes

Modern evidence demonstrates that structured weight management strategies reduce:

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE)

Myocardial infarction

Stroke

Cardiovascular mortality

All-cause mortality

This confirms that weight loss is not merely cosmetic — it is cardioprotective.

5. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Have Changed Preventive Cardiology

New-generation pharmacotherapies, particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists, have:

Demonstrated significant weight reduction

Shown direct cardiovascular event reduction in high-risk populations

Improved metabolic and inflammatory parameters

These agents have redefined obesity treatment as a core cardiovascular intervention.

6. Lifestyle Intervention Remains Foundational

Despite pharmacologic advances, sustainable cardiovascular protection requires:

Nutritionally structured dietary patterns

Resistance and aerobic exercise

Sleep optimization

Stress regulation

Behavioral reinforcement

Medication without lifestyle change increases risk of weight regain.

7. Obesity Is a Chronic Disease Requiring Long-Term Strategy

Data show that discontinuing anti-obesity medications often leads to substantial weight regain within 12–24 months.

This reinforces:

The chronic disease model of obesity

The need for sustained therapeutic planning

Early discussion of long-term management expectations

8. Cardiologists Must Integrate Weight Management Into Practice

Modern cardiovascular prevention demands:

Active discussion of weight as a modifiable risk factor

Personalized risk assessment

Integration of obesity pharmacotherapy when indicated

Multidisciplinary collaboration

Weight management is no longer optional — it is standard of care.

9. Personalized Treatment Is Essential

Patients with:

Coronary artery disease

Heart failure (especially HFpEF)

Atrial fibrillation

Type 2 diabetes

Require tailored weight strategies aligned with cardiac risk profiles.

10. The Implementation Gap Is the Next Frontier

The evidence base is strong. The challenge now lies in:

Access and affordability of treatment

Reducing stigma in clinical settings

Addressing health inequities

Scaling preventive cardiometabolic care globally

Modest weight loss is one of the highest-yield interventions in modern preventive cardiology. The shift from viewing obesity as a lifestyle issue to recognizing it as a chronic, treatable cardiovascular risk condition represents one of the most important paradigm changes of the decade.

The science is clear: even small reductions in body weight can meaningfully lower heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality risk. The future of heart disease prevention is inseparable from structured, sustained weight management.

Author’s Note

Obesity and cardiovascular disease are deeply interconnected conditions that continue to shape the global burden of morbidity and mortality. This article was written to bridge the gap between rapidly evolving scientific evidence and practical clinical understanding. Over the past three years, landmark consensus statements, large-scale umbrella reviews, and cardiovascular outcome trials have transformed how we approach weight management in cardiology. What was once considered adjunctive lifestyle advice is now recognized as a central, evidence-based pillar of cardiovascular risk reduction.

The goal of this piece is not to promote any single intervention, but to synthesize current high-quality data into a clinically meaningful framework. Modern pharmacotherapies, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, bariatric metabolic surgery, and structured lifestyle interventions, each have a role — but their application must be individualized, evidence-driven, and sustained. The emerging data on weight regain after medication discontinuation further reinforce the chronic disease model of obesity and the necessity for long-term strategies.

As an internist engaged in cardiometabolic medicine, my intent is to encourage clinicians to integrate structured weight management into routine cardiovascular care, and to empower patients to view obesity treatment as legitimate, medical, and preventative — not cosmetic.

The science has matured. Implementation must now follow with the same rigor, compassion, and commitment to long-term outcomes that define modern preventive cardiology.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Managing Diabesity: A Complete Guide to Weight Loss and Blood Sugar Control | DR T S DIDWAL

The BMI Paradox: Why "Normal Weight" People Still Get High Blood Pressure | DR T S DIDWAL

Breakthrough Research: Leptin Reduction is Required for Sustained Weight Loss | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Chen, X., Zhang, X., Xiang, X., et al. (2025). Effects of weight control interventions on cardiovascular outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. International Journal of Obesity, 49, 1911–1920. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01860-z

Gilbert, O., Gulati, M., Gluckman, T. J., Kittleson, M. M., Rikhi, R., Saseen, J. J., & Tchang, B. G. (2025). 2025 Concise clinical guidance: An ACC expert consensus statement on medical weight management for optimization of cardiovascular health: A report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 86(7), 536–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2025.05.024

Hritani, R., Al Rifai, M., Mehta, A., & German, C. (2023). Obesity management for cardiovascular disease prevention. Obesity Pillars, 7, Article 100069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100069

Huang, Y., Au, K., Mahawar, K., Pan, A., Shabbir, A., Zheng, M.-H., Ghanem, O., Yang, W., & International Obesity Society Working Group on Cardiometabolic Diseases. (2025). Tailored weight-management recommendations for obesity patients with cardiovascular-metabolic diseases. The Innovation, 7(1), Article 101085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2025.101085

West, S., Scragg, J., Aveyard, P., Oke, J. L., Willis, L., Haffner, S. J. P., Knight, H., Wang, D., Morrow, S., Heath, L., Jebb, S. A., & Koutoukidis, D. A. (2026). Weight regain after cessation of medication for weight management: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 392, Article e085304. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2025-085304