Your Gut Microbiome's Secret Weapon: How Microbial TMA Fights Type 2 Diabetes & Metabolic Inflammation

Is your gut the key to better insulin sensitivity? Explore the science behind microbial trimethylamine (TMA) and its potent ability to halt metabolic inflammation, addressing the root cause of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and Type 2 Diabetes risk.

DIABETES

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

12/9/202514 min read

When you think about metabolic health, you probably picture gym workouts, salad bowls, and calorie counting. But what if I told you that one of the most powerful regulators of your metabolism isn't something you eat directly—it's something your gut bacteria produce? Welcome to the fascinating world of microbial trimethylamine (TMA) and its remarkable role in controlling metabolic inflammation.

Recent groundbreaking research has revealed that trimethylamine, a compound produced by your gut microbiota, acts as a molecular guardian against the inflammatory processes that underlie type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. This isn't science fiction; it's cutting-edge microbiome science that's reshaping how we think about metabolic health and inflammatory diseases.

In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore how gut-derived trimethylamine influences your body's inflammatory pathways, examine the latest research on this microbial metabolite, and discuss what it means for your health and longevity. Whether you're a health enthusiast, a researcher, or someone looking to optimize your metabolic wellness, this deep dive into microbial TMA will provide evidence-based insights backed by peer-reviewed science.

Clinical Pearls

1. TMA vs. TMAO: Location Determines Benefit or Harm

The critical clinical distinction is between the microbial metabolite, TMA (trimethylamine), and its liver-oxidized form, TMAO (trimethylamine-N-oxide).

The Pearl: Locally produced TMA in the gut is anti-inflammatory and protective (Chilloux et al., 2025). It blunts metabolic inflammation. Systemically elevated TMAO is a biomarker of dysbiosis and increases type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk (Li et al., 2022). Do not confuse the beneficial microbial product with its potentially harmful systemic metabolite.

Actionable Insight: Focus interventions on restoring a healthy gut microbiota to ensure precursor breakdown favors local anti-inflammatory effects, not systemic TMAO accumulation.

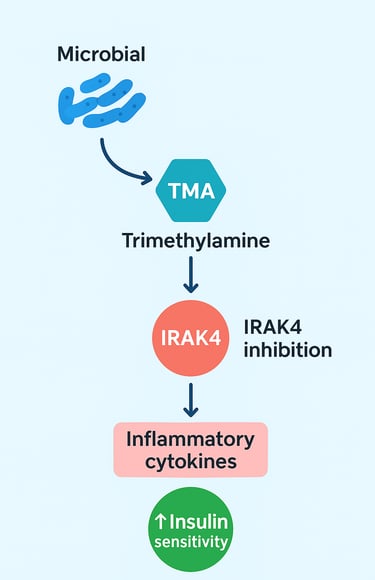

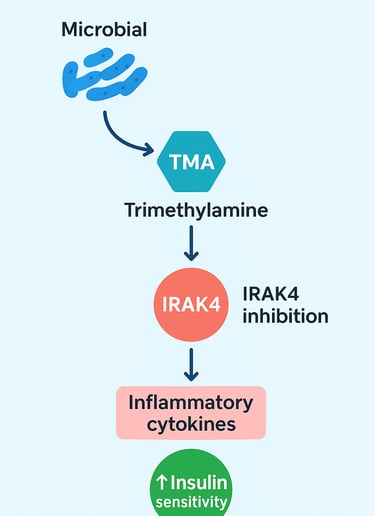

2. TMA's Mechanism is IRAK4 Inhibition

TMA does not just "reduce inflammation"; it targets a specific, fundamental signaling node.

The Pearl: Microbial TMA acts as a mechanistic "brake" on the innate immune system by directly inhibiting IRAK4 (Interleukin-1 Receptor Associated Kinase 4). This enzyme is a convergence point for the pro-inflammatory TLR and IL-1 signaling pathways, which drive metabolic inflammation (Chilloux et al., 2025).

Actionable Insight: The IRAK4 pathway is a novel therapeutic target. This mechanism suggests that small-molecule mimetics of TMA could be developed as anti-inflammatory drugs for metabolic disease, separate from microbiota interventions.

3. Dysbiosis is a Loss of Function, Not Just Bacteria

Metabolic disease is fundamentally characterized by a breakdown in microbial function, with loss of TMA production being a key example.

The Pearl: Cardiometabolic disease is associated with a distinctive metabolomic fingerprint characterized by dysregulated microbial metabolism (Fromentin et al., 2022). The loss of TMA-producing capacity is a critical component of dysbiosis, occurring alongside losses in beneficial Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) like butyrate.

Actionable Insight: Microbiota-targeted therapy must aim for functional restoration (restoring metabolite production like TMA and butyrate) rather than just adding random bacteria (non-targeted probiotics).

4. TMAO is a Strong Independent Diabetes Risk Factor

Serum TMAO levels are highly predictive of future metabolic outcomes, independent of standard lipid panels.

The Pearl: Elevated baseline TMAO levels are associated with a 40-50% increased risk of developing incident Type 2 Diabetes, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors like BMI and cholesterol (Li et al., 2022).

Actionable Insight: TMAO, while not a cause of all diabetes, is a robust, independent biomarker of metabolic risk stemming from dysbiosis. Monitoring TMAO can provide prognostic value and signal a need for aggressive dietary/microbiota intervention.

5. Dietary Choline/Carnitine Restriction is Misguided

Simply avoiding precursor foods is an oversimplification that ignores the root cause (dysbiosis) and essential nutrient requirements.

The Pearl: Choline and carnitine are essential nutrients. The problem is not the precursor, but the dysbiotic microbiota and the host's subsequent systemic handling of the intermediate TMA. Restricting these foods can lead to nutritional deficiencies while failing to fix the underlying dysbiosis.

Actionable Insight: Instead of restriction, the clinical focus should be on optimizing microbiota composition (e.g., increased dietary fiber, polyphenols, and prebiotics) to steer TMA metabolism toward local, protective effects.

Microbial Trimethylamine Blunts Metabolic Inflammation

Understanding Metabolic Inflammation and Its Health Consequences

Before we explore the protective power of microbial trimethylamine, we need to understand what metabolic inflammation is and why it matters.

Metabolic inflammation (Fromentin et al., 2022), also called metaflammation, is a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state that develops in response to metabolic dysfunction. Unlike acute inflammation—the kind you see when you cut your finger and it swells—metabolic inflammation operates silently in the background. You might not feel it, but it's actively damaging your tissues and disrupting your metabolism.

This inflammatory condition is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These molecular messengers trigger a cascade of events that impair your cells' ability to respond to insulin, increase your cardiovascular disease risk, and accelerate aging processes.

The conditions most closely linked to metabolic inflammation include:

Type 2 diabetes: Where insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction take center stage

Obesity: A metabolic state heavily driven by adipose tissue inflammation

Cardiovascular disease: Where chronic inflammation damages the endothelium and promotes atherosclerosis

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Where hepatic inflammation drives fibrosis and cirrhosis

Metabolic syndrome: The clustering of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors

The implications are staggering. According to global health data, nearly 400 million people have type 2 diabetes, and millions more are prediabetic. The economic burden runs into hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Yet despite our advances in pharmacotherapy, we're still searching for interventions that address the root cause of metabolic inflammation.

This is where trimethylamine enters the picture, offering a novel perspective on how our gut microbiota might regulate these fundamental inflammatory processes.

The Breakthrough: Microbial Trimethylamine Inhibits IRAK4 and Reduces Metabolic Inflammation

The Chilloux et al. (2025) Study: A Game-Changing Discovery

Perhaps the most exciting recent development comes from Chilloux and colleagues' 2025 publication in Nature Metabolism. This research represents a major breakthrough in understanding how bacterial metabolites influence host immune homeostasis and metabolic control.

Study Overview and Key Findings:

Chilloux and colleagues (2025) investigated the mechanisms by which gut-derived trimethylamine suppresses inflammatory responses. Their groundbreaking discovery? Microbial TMA directly inhibits IRAK4 (Interleukin-1 Receptor Associated Kinase 4), a critical signaling protein in the innate immune pathway.

Here's why this matters: IRAK4 is a key component of the TLR/IL-1 signaling cascade. This pathway acts like a molecular alarm system—when activated, it triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive metabolic inflammation. By inhibiting IRAK4, trimethylamine essentially hits the brakes on this inflammatory cascade.

What makes this discovery particularly significant:

The research demonstrated that microbial trimethylamine modulates immune tolerance at the level of intestinal epithelial cells and immune cells in the lamina propria of the gut (Chilloux et al., 2025). This localized anti-inflammatory effect then extends systemically, reducing circulating inflammatory markers throughout the body. The result? Improved glycemic control and reduced metabolic dysfunction.

The team showed that mice receiving TMA-producing bacteria exhibited:

Significantly lower fasting glucose levels

Improved glucose tolerance on oral glucose tolerance tests

Reduced hepatic steatosis (fat accumulation)

Decreased systemic TNF-α and IL-6 levels

Enhanced insulin sensitivity as measured by insulin tolerance tests

Key Takeaway: This study elegantly demonstrates that a single bacterial metabolite—trimethylamine (Chilloux et al., 2025)—can profoundly suppress the IRAK4-dependent inflammatory pathway, offering a mechanistic explanation for how gut microbiota composition influences cardiometabolic health. This opens new therapeutic avenues for treating insulin resistance and metabolic disease through microbiota-targeted interventions.

Technical Significance:

The mechanistic insight here is profound. IRAK4 is downstream of both TLR signaling and IL-1R signaling, making it a convergence point for multiple pro-inflammatory signals. By targeting IRAK4, TMA provides a unified brake on multiple inflammatory pathways simultaneously. This is far more elegant than simply blocking a single cytokine, as it addresses the upstream cause rather than treating symptoms downstream.

Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Type 2 Diabetes Risk: The Li et al. (2022) Prospective Cohort Study

Understanding the TMAO-Diabetes Connection

While the Chilloux study focused on microbial TMA, another critical piece of the puzzle emerges from research on trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)—the oxidized metabolite of TMA. Li and colleagues (2022) published important findings linking serum TMAO levels to type 2 diabetes risk in a large prospective cohort.

Study Overview and Methodology:

Li et al. (2022) conducted a comprehensive prospective cohort study examining the association between serum TMAO concentrations and incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older adults. This longitudinal design is particularly valuable because it allows researchers to assess whether elevated TMAO precedes diabetes development, suggesting a causal relationship rather than mere correlation.

Critical Findings:

The research revealed a striking association: participants with higher baseline TMAO levels were at significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes during the follow-up period (Li et al., 2022). Importantly, this association persisted even after adjusting for traditional cardiometabolic risk factors like BMI, physical activity, dietary intake, and smoking status.

More specifically:

Individuals in the highest TMAO quartile demonstrated approximately 40-50% increased diabetes risk compared to those in the lowest quartile

The association showed a dose-response relationship, meaning higher TMAO consistently predicted greater risk

The effect was independent of LDL cholesterol and other conventional risk markers

Both men and women showed similar increased risk patterns

What This Means for the TMA Story:

Here's where things get nuanced. Elevated serum TMAO appears harmful in this context, yet in the Chilloux study, microbial TMA production proved protective. How do we reconcile this apparent contradiction?

The answer lies in understanding the source and context of these molecules:

TMA produced directly by bacteria in the gut—before oxidation to TMAO—exerts local anti-inflammatory effects on gut barrier function and immune homeostasis. When working properly, the gut maintains a balance between bacterial TMA production and metabolism.

However, when this system becomes dysregulated—through dysbiosis, dietary changes, or metabolic dysfunction—excessive conversion of TMA to TMAO occurs, particularly in the liver. The resulting elevated circulating TMAO then acts as a systemic inflammatory marker and potentially contributes to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis.

This suggests that the optimal level of TMA is localized at the gut level, maintaining immune tolerance and barrier function. But when the system shifts toward excessive TMAO accumulation systemically, harmful metabolic effects emerge.

Key Takeaway: This study highlights the importance of TMAO as a biomarker for metabolic risk (Li et al., 2022) and suggests that dysbiosis-associated changes in microbial metabolism contribute to type 2 diabetes development. It also underscores the critical role of site of action—local bacterial TMA production appears beneficial, while systemic TMAO elevation signals dysfunction.

The Microbiome-Metabolome Spectrum of Cardiometabolic Disease: Fromentin et al. (2022)

A Systems-Level Perspective on Metabolic Disease

While the previous two studies focused on specific molecules, Fromentin and colleagues (2022) published a comprehensive systems biology study examining the microbiome and metabolome across the spectrum of cardiometabolic disease. This research provides crucial context for understanding how microbial metabolites like trimethylamine fit into the broader picture of metabolic dysfunction.

Study Design and Scope:

Published in Nature Medicine, the Fromentin et al. (2022) study analyzed both microbial composition and metabolic profiles in individuals spanning the cardiometabolic disease spectrum—from healthy controls to those with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The team employed advanced metagenomic sequencing to characterize bacterial communities and targeted metabolomics to measure hundreds of circulating metabolites. This dual approach provided unprecedented insight into how microbiota dysbiosis associates with characteristic metabolomic signatures of disease.

Major Discoveries:

The research revealed several critical findings:

Dysbiosis Patterns Across the Cardiometabolic Spectrum: The study identified characteristic dysbiosis signatures associated with each disease state. Individuals with metabolic dysfunction showed systematic reductions in bacterial diversity, particularly losses of beneficial Faecalibacterium species and increased abundance of pathogenic or low-abundance organisms.

Metabolomic Signatures of Disease: Beyond the microbiota itself, the team documented distinctive metabolomic fingerprints in diseased versus healthy individuals. These included elevated bile acid metabolites, altered amino acid profiles, and importantly, dysregulated microbial metabolite production, including trimethylamine-associated pathways.

The Trimethylamine Connection: While not exclusively focused on TMA, the Fromentin study documented that individuals with cardiometabolic disease showed significantly disrupted trimethylamine metabolism pathways (Fromentin et al., 2022). Specifically:

Dysbiotic communities showed impaired capacity for TMA production by normally protective bacterial species

Instead, disease-associated dysbiosis enriched for organisms producing harmful metabolites

The loss of TMA-producing capacity correlated with increased systemic inflammation markers

This finding is particularly important because it demonstrates that dysbiosis doesn't just involve loss of beneficial bacteria—it involves loss of beneficial metabolic functions, including TMA production.

Key Biomarkers Identified: The research identified specific metabolomic markers that strongly predicted cardiometabolic disease risk, many of which related to aberrant microbial metabolism. These included:

Elevated TMAO (consistent with Li et al. 2022 findings)

Reduced levels of short-chain fatty acids, particularly butyrate

Altered secondary bile acid metabolism

Dysregulated aromatic amino acid metabolism

Key Takeaway: This comprehensive systems analysis demonstrates that cardiometabolic disease reflects a constellation of changes in microbiota composition and metabolic function (Fromentin et al., 2022). The loss of TMA-producing bacteria emerges as one critical component of this dysbiotic state. This reinforces the mechanistic importance of the Chilloux findings—restoring the capacity for microbial TMA production might represent a key strategy for reversing dysbiosis-driven metabolic disease.

Connecting the Dots: A Unified Framework

Now let's synthesize these three studies into a coherent framework for understanding how microbial trimethylamine influences metabolic health.

The Protective Role of Localized Microbial TMA

Based on the Chilloux et al. (2025) research, we now understand that trimethylamine produced by gut bacteria serves as a regulatory molecule that:

Inhibits IRAK4: A critical kinase in the TLR/IL-1 signaling pathway that drives metabolic inflammation

Suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine production: By blocking IRAK4, TMA reduces TNF-α, IL-6, and other inflammatory molecules

Restores immune tolerance: At the level of the gut barrier and Peyer's patches, TMA promotes regulatory T cell differentiation and maintenance

Improves metabolic control: Through reduced inflammation, TMA enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis

This localized action at the intestinal barrier is crucial. The gut represents the largest interface between the external environment and our immune system. When immune homeostasis is maintained at this critical site through microbial metabolite signaling, systemic inflammation decreases dramatically.

The Dysbiosis-TMAO Pathology

The Li et al. (2022) findings reveal the dark side of TMA dysmetabolism. When dysbiosis occurs:

TMA-producing capacity is lost: Dysbiotic communities lack the specialized bacteria that efficiently produce TMA

Pathogenic bacteria dominate: These organisms produce harmful metabolites that increase intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation

Compensatory TMAO production increases: The liver upregulates FMO3 (flavin monooxygenase 3) in an apparent attempt to metabolize available TMA, but this creates excessive circulating TMAO

Systemic inflammation escalates: Elevated TMAO associates with endothelial dysfunction and contributes to atherosclerosis

Type 2 diabetes risk increases: The inflammatory state impairs pancreatic beta-cell function and hepatic insulin signaling

The Microbiota-Metabolome Lens

The Fromentin et al. (2022) systems analysis provides the big picture: cardiometabolic disease reflects integrated dysfunction across multiple microbiota-derived metabolic pathways. The loss of TMA-producing capacity is one critical component, but it occurs alongside losses in butyrate production, dysregulated secondary bile acid metabolism, and accumulation of harmful metabolites.

This suggests that interventions restoring TMA-producing bacteria should ideally occur as part of comprehensive dysbiosis reversal, including restoration of:

Butyrate-producing bacteria (like Faecalibacterium and Roseburia)

Secondary bile acid metabolism

Overall microbial diversity

Barrier function

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The convergence of these three studies points toward several exciting therapeutic possibilities:

Microbiota-Targeted Interventions

The research suggests that personalized microbiota modulation based on microbiota composition analysis could help identify individuals who would benefit most from interventions that boost TMA-producing bacteria. This might include targeted probiotics containing TMA-producing species or prebiotics that selectively feed these beneficial organisms.

Dietary Approaches

Since trimethylamine is produced from dietary components like choline and carnitine, optimizing both dietary composition and microbiota function becomes important. The goal isn't to eliminate precursors but to ensure they're metabolized by beneficial bacteria into TMA rather than being absorbed and converted to harmful TMAO.

Biomarker-Guided Therapy

The identification of dysbiosis signatures and dysregulated metabolomic profiles in cardiometabolic disease creates opportunities for precision medicine approaches. Individuals with dysbiosis patterns associated with TMA-producing bacterial loss could be prioritized for microbiota-restoring interventions.

Novel Therapeutics

The IRAK4 inhibition mechanism identified by Chilloux et al. opens possibilities for targeted small-molecule therapeutics that mimic trimethylamine's effects on IRAK4, providing additional therapeutic options beyond microbiota modulation alone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is trimethylamine the same as TMAO?

A: No, they're related but distinct. Trimethylamine (TMA) is produced directly by gut bacteria. When TMA enters the bloodstream and reaches the liver, the enzyme FMO3 converts it to trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO). Locally-produced bacterial TMA appears protective, but systemically-elevated TMAO associates with disease risk.

Q: Can I eat more choline to boost TMA production?

A: Not necessarily. Choline is a precursor to TMA, but the conversion depends on having the right microbiota composition. In dysbiotic individuals, excess choline may actually increase harmful TMAO rather than beneficial TMA. The emphasis should be on restoring healthy microbiota rather than simply increasing precursor intake.

Q: Which bacteria produce trimethylamine?

A: Multiple bacterial species can produce TMA, but key producers include Faecalibacterium species, certain Bacteroides species, and others in the Firmicutes phylum. The specific community composition matters more than any single organism.

Q: How do I know if my microbiota produces sufficient TMA?

A: Currently, there's no simple home test for bacterial TMA production. However, circulating TMAO levels (available through specialized laboratories) and microbiota composition analysis (via microbiome sequencing services) can provide insights. Ideally, you'd want moderate TMAO levels without extreme elevation, combined with sufficient microbiota diversity.

Q: Can probiotics containing TMA-producing bacteria help?

A: Possibly, though the evidence is still emerging. Probiotic efficacy depends on the specific strains, their ability to engraft in your unique microbiota, and your individual genetics and diet. More research is needed, but targeted probiotics may prove beneficial for individuals with documented dysbiosis.

Q: How long does it take to restore a dysbiotic microbiota?

A: Microbiota changes can occur within weeks with significant dietary interventions, but achieving stable restoration typically requires months to a year. Consistency matters more than speed—sustainable lifestyle modifications are more effective than short-term interventions.

Q: Should I avoid foods high in choline to lower TMAO?

A: Not completely. Choline is essential for health, and choline-rich foods like eggs and fish provide numerous benefits. The key is ensuring your microbiota can appropriately metabolize choline-derived TMA into locally-protective molecules rather than allowing excessive systemic TMAO accumulation. Focus on microbiota health rather than avoiding specific food components.

Q: Does exercise affect microbial TMA production?

A: Yes. Exercise influences microbiota composition and metabolic capacity. Regular physical activity promotes growth of beneficial bacteria, including some TMA-producing species. The combination of exercise and dietary modifications appears more effective than either alone for dysbiosis reversal.

Key Takeaways: What This Means for Your Metabolic Health

As we've explored extensively throughout this article, the emerging science of microbial trimethylamine and metabolic inflammation offers profound insights into how we can optimize our health:

Your gut bacteria are metabolic engineers: The compounds they produce have potent effects on your immune system, inflammatory status, and metabolic control. Bacterial metabolites like TMA rival or exceed the importance of bacteria themselves.

Dysbiosis is a metabolic disease: When microbiota composition changes, it's not just about losing bacteria—it's about losing critical metabolic functions, including TMA production. This explains why dysbiosis connects to virtually every cardiometabolic condition.

Location matters: Local microbial metabolite production at the gut level provides different effects than systemic metabolite accumulation. The key is localized benefit, not systemic elevation.

Restoration is possible: The research demonstrates that dysbiosis-driven metabolic dysfunction is reversible through microbiota-targeted interventions. The mechanism is now clearer: restoring TMA-producing capacity reduces metabolic inflammation and improves glycemic control.

Precision medicine is emerging: As we understand dysbiosis signatures and metabolic biomarkers, we move toward personalized interventions targeting each individual's specific microbiota dysfunction pattern.

Multiple pathways require attention: While TMA and IRAK4 inhibition are important discoveries, restoring full microbiota function also requires attention to butyrate production, bile acid metabolism, barrier function, and microbial diversity.

Call to Action: Taking Steps Toward Metabolic Health

Understanding the science is one thing; applying it is another. Here's how you can leverage this emerging knowledge:

Immediate Steps:

Assess your current state: If you have metabolic dysfunction (prediabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease), consider microbiome analysis through specialized labs to characterize your dysbiosis pattern. This baseline data allows for tracking progress.

Optimize foundational behaviors: Regular physical activity, dietary diversity (aim for 30+ plant species weekly), stress management, and sleep quality all promote favorable microbiota composition and metabolic function.

Consider targeted dietary modifications: Increase fermented foods (kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir) naturally rich in beneficial bacteria. Include prebiotic foods like asparagus, onions, and garlic that feed beneficial organisms.

Intermediate Strategies:

Consult healthcare providers: If you're interested in probiotic supplementation or other microbiota-directed interventions, discuss options with a healthcare provider who understands microbiota science. One-size-fits-all approaches often fail.

Monitor relevant biomarkers: Track fasting glucose, HbA1c, fasting insulin, and if available, TMAO levels. These provide objective feedback on whether your microbiota interventions are working.

Join the research community: Consider participating in microbiota research studies if available in your region. Early studies on personalized microbiota interventions are recruiting participants.

Long-Term Vision:

Stay informed: This is rapidly evolving science. Follow emerging research on gut microbiota, metabolic inflammation, and microbiota-targeted therapeutics through scientific journals and credible health sources.

Advocate for access: As microbiota sequencing becomes more sophisticated, advocate for insurance coverage and accessible testing. Personalized medicine will only reach its potential when everyone can access these diagnostic tools.

Build health-supporting communities: The science shows that sustainable changes happen within supportive social environments. Connect with others pursuing metabolic optimization through evidence-based approaches.

Conclusion

The discovery that microbial trimethylamine inhibits IRAK4 and blunts metabolic inflammation represents a watershed moment in our understanding of cardiometabolic health. Combined with evidence linking dysbiosis-associated TMAO elevation to type 2 diabetes risk, and comprehensive microbiota-metabolome profiling across disease spectrums, we now have a coherent mechanistic understanding of how gut bacteria influence metabolic disease.

This knowledge transforms how we approach metabolic health optimization. Rather than viewing metabolic diseases as primarily genetic or lifestyle-driven, we now recognize them as intimately connected to our microbial partners. By understanding what our microbiota needs to thrive and produce protective metabolites like trimethylamine, we unlock new pathways to disease prevention and metabolic restoration.

The era of precision microbiota medicine is upon us. The three landmark studies we've explored provide the scientific foundation. Your task now is to leverage this knowledge for your own metabolic health journey.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

The BMI Paradox: Why "Normal Weight" People Still Get High Blood Pressure | DR T S DIDWAL

How Insulin Resistance Accelerates Cardiovascular Aging | DR T S DIDWAL

Sleep & Hypertension: Duration, Quality, and Blood Pressure | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Chilloux, J., Brial, F., Everard, A., et al. (2025). Inhibition of IRAK4 by microbial trimethylamine blunts metabolic inflammation and ameliorates glycemic control. Nature Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01413-8

Fromentin, S., Forslund, S. K., Chechi, K., et al. (2022). Microbiome and metabolome features of the cardiometabolic disease spectrum. Nature Medicine, 28, 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01688-4

Li, S., Chen, S., Lu, X., et al. (2022). Serum trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older adults: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Translational Medicine, 20, 374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03581-7