Why Thigh Muscle Thickness May Be the Missing Biomarker of Metabolic and Cardiorespiratory Health

Is thigh muscle thickness the missing link in metabolic and aerobic health? Emerging research connects muscle mass to VO₂ max and liver health.

EXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/21/202614 min read

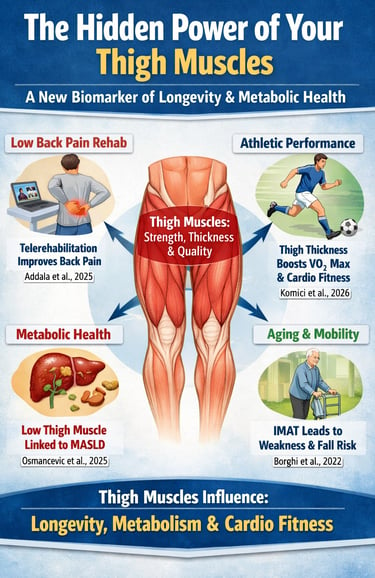

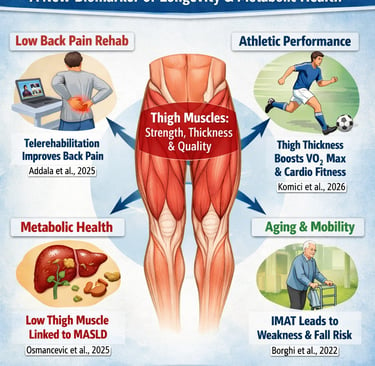

When we think about muscle health, most conversations revolve around aesthetics or athletic performance. But emerging research suggests your thigh muscle strength, muscle thickness, and even muscle quality may be among the most powerful predictors of long-term health outcomes. From low back pain rehabilitation to cardiorespiratory fitness, from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) to age-related decline in functional mobility, the science is converging on one striking conclusion: your thighs are not just locomotor muscles — they are metabolic and physiological regulators.

A 2025 randomized clinical trial demonstrated that targeted quadriceps and hamstring strengthening via telerehabilitation significantly improved outcomes in individuals with chronic low back pain (Abdala et al., 2025). Meanwhile, performance physiology research shows that greater thigh muscle thickness is independently associated with higher VO₂ max and superior ventilatory efficiency, linking peripheral muscle mass to central cardiovascular performance (Komici et al., 2026).

The metabolic implications are equally compelling. Large population imaging data reveal that lower thigh muscle mass is independently associated with increased risk of MASLD, even after adjusting for obesity and visceral fat (Osmancevic et al., 2025). In older adults, elevated intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) within the thigh predicts reduced strength and impaired mobility — critical determinants of fall risk and mortality (Borghi et al., 2022).

Taken together, these findings redefine the thigh as a critical organ of metabolic health, cardiorespiratory resilience, and healthy aging — not merely a muscle group for movement.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Second Spine" Effect

Scientific Perspective: The quadriceps and hamstrings act as distal stabilizers for the pelvic girdle. Weakness here increases the $lumbosacral$ shear force and forces the $erector$ $spinae$ to overwork to maintain postural integrity.

Patient Perspective: "Your back pain might actually be a leg strength problem. Think of your thighs as the 'shocks' on a car; if the shocks are worn out, every bump in the road hits the frame (your spine) much harder."

2. Quality Over Occupancy (The Marble vs. Lean Steak)

Scientific Perspective: Functional decline in aging is more highly correlated with Intermuscular Adipose Tissue (IMAT) than simple cross-sectional area. Fat infiltration disrupts lateral force transmission between muscle fibers.

Patient Perspective: "Two legs can look the same size on the outside, but one can be 'marbled' with fat like a ribeye steak. We aren't just training to keep your legs big; we are training to clear out the 'clutter' so your muscles can actually fire."

3. The Thigh as a "Metabolic Sponge"

Scientific Perspective: Skeletal muscle is responsible for approximately 80% of postprandial glucose uptake. Large muscle groups like the glutes and quads are the primary systemic buffers against hyperinsulinemia and subsequent hepatic lipogenesis (MASLD).

Patient Perspective: "Every time you strengthen your thighs, you are building a bigger 'sponge' to soak up the sugar in your blood. This takes the pressure off your liver and helps prevent metabolic 'flooding' that leads to fatty liver disease."

4. The Peripheral "Turbocharger"

Scientific Perspective: Thigh muscle thickness is a determinant of ventilatory efficiency ($VE/VCO_2$ slope). Higher local muscular density improves oxygen extraction ($a-vO_2$ difference), which reduces the central demand on the heart and lungs during exertion.

Patient Perspective: "Stronger legs make your heart’s job easier. If your legs are efficient at using oxygen, you won't feel 'out of breath' as quickly because your lungs don't have to work as hard to keep the muscles fueled."

5. Digital Accessibility is a Clinical "Green Flag"

Scientific Perspective: Telerehabilitation for strength training shows non-inferiority to in-person clinical supervision for LBP outcomes, provided the protocol is progressive and targets the $quadriceps/hamstring$ ratio.

Patient Perspective: "You don't need a high-tech clinic to fix chronic pain. Modern science shows that doing the right leg exercises in your living room via a tablet is just as effective for your back as driving to an appointment twice a week."

The Hidden Power of Your Thigh Muscles: A New Biomarker of Longevity and Metabolic Health

Study 1: Thigh Strength in Low Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions globally, affecting hundreds of millions of people and representing a leading cause of disability. A 2025 randomized controlled trial by Abdala et al. published in the Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies investigated whether telerehabilitation — the delivery of physical therapy through digital platforms — could be an effective method for strengthening thigh muscles in individuals suffering from LBP.

The study enrolled volunteers with low back pain and divided them into groups receiving either telerehabilitation-based thigh muscle strengthening or a control condition. The intervention specifically targeted the quadriceps and hamstrings, muscle groups that, when weak, are implicated in destabilizing pelvic and lumbar mechanics.

Key Findings

The results were encouraging. Participants who underwent the telerehabilitation strength training protocol demonstrated meaningful improvements in thigh muscle strength compared to controls. Importantly, these gains were achievable without in-person clinical supervision, suggesting that digital health platforms can extend the reach of musculoskeletal care to populations with limited access to traditional therapy.

The study adds to a rapidly expanding evidence base suggesting that the quadriceps and hamstrings serve as critical stabilizers of the lumbar spine. Weakness in the anterior and posterior thigh musculature creates compensatory stress on the lower back, perpetuating the pain cycle. Strengthening these muscles, even remotely, appears to interrupt this cycle in clinically meaningful ways.

Thigh muscle strengthening via telerehabilitation is an effective and accessible intervention for reducing the burden of low back pain, validating digital health tools as legitimate clinical delivery methods.

This finding has far-reaching implications for healthcare systems straining under the weight of musculoskeletal chronic conditions, particularly in post-pandemic contexts where remote care has become normalized.

Study 2: Thigh Muscle Thickness, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Ventilatory Efficiency in Soccer Athletes

In elite sport, the quest to optimize performance metrics is relentless. A 2026 study by Komici et al., published in Scientific Reports, examined the associations between thigh muscle thickness — measured using ultrasound — and two critical markers of aerobic performance: cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO₂ slope) in male soccer athletes.

Soccer is a sport that demands repeated high-intensity efforts interspersed with lower-intensity recovery, placing extraordinary demands on both the cardiovascular system and the skeletal musculature. The researchers hypothesized that greater thigh muscle mass, as indicated by muscle thickness, would correlate with superior aerobic capacity and more efficient gas exchange during exercise.

Key Findings

The study found significant associations between thigh muscle thickness and both cardiorespiratory fitness and ventilatory efficiency. Athletes with greater thigh muscle thickness demonstrated higher VO₂ max values and more favorable VE/VCO₂ slopes, suggesting that the sheer volume of thigh musculature plays a role not only in force production but also in the body's capacity to deliver and utilize oxygen during sustained physical effort.

The ventilatory efficiency finding is particularly noteworthy. VE/VCO₂ slope is a sensitive marker of cardiopulmonary reserve, typically evaluated in heart failure research. Its correlation with thigh muscle thickness in healthy athletes suggests that peripheral muscle mass may influence central cardiorespiratory dynamics — a physiologically fascinating link that challenges the traditional view of muscle as merely mechanical tissue.

From a practical standpoint, coaches and sports scientists may find that monitoring thigh muscle thickness via portable ultrasound offers a valuable, non-invasive window into an athlete's aerobic potential and readiness.

In male soccer athletes, greater thigh muscle thickness is associated with superior cardiorespiratory fitness and ventilatory efficiency, suggesting that peripheral muscle mass meaningfully influences aerobic performance capacity.

This underscores the importance of muscle hypertrophy programs not just for strength sports, but for endurance-based team sports where aerobic engine size is a performance limiter.

Study 3: Thigh Muscles and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

Overview

One of the most intriguing and clinically urgent findings comes from a 2025 investigation by Osmancevic et al., published in Liver International. Drawing on data from the large-scale SCAPIS/IGT-Microbiota study, this research explored the relationship between thigh muscle composition and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) — a condition formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that is rapidly becoming a global public health crisis.

MASLD is characterized by excessive fat deposition in the liver in the absence of heavy alcohol use and is closely tied to insulin resistance, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. The researchers used MRI-derived measurements to assess thigh muscle volume and quality, examining whether lean muscle mass in the thigh region was associated with the presence or severity of hepatic steatosis.

Key Findings

The findings revealed a meaningful inverse association: individuals with lower thigh muscle mass were more likely to exhibit markers of MASLD. This relationship held even after adjusting for traditional metabolic risk factors such as body mass index and visceral fat, suggesting that thigh muscle quantity and quality may independently influence liver metabolic health.

This is biologically plausible. Skeletal muscle is the primary site of insulin-mediated glucose uptake in the body. When thigh muscle mass is reduced — as occurs in sarcopenia or sedentary lifestyle — glucose disposal is impaired, promoting hyperinsulinemia and the hepatic lipogenesis that drives fatty liver disease. Put simply, more thigh muscle means better metabolic housekeeping for your liver.

The study also adds important nuance to how we conceptualize metabolic disease risk. Rather than focusing exclusively on fat mass or visceral adiposity, clinicians may benefit from assessing regional muscle mass — and particularly the thigh — as an early indicator of metabolic vulnerability.

Lower thigh muscle mass is independently associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, reinforcing skeletal muscle as a critical metabolic organ whose decline accelerates liver disease pathology.

This finding should prompt clinicians managing metabolic disease to incorporate muscle preservation strategies — including resistance training and nutritional optimization — into their standard care frameworks.

Study 4: Thigh Intermuscular Adipose Tissue, Muscle Strength, and Functional Mobility in Older Adults

Overview

The fourth study pivots to the aging population, where the interplay between muscle quality and functional independence is of paramount importance. Borghi et al. (2022), publishing in Medicine, investigated the interrelationships among thigh intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), cross-sectional area (CSA), muscle strength, and functional mobility in older subjects.

Intermuscular adipose tissue refers to fat that infiltrates between muscle fibers and within muscle compartments — distinct from subcutaneous fat and widely recognized as a marker of poor muscle quality. As we age, muscle undergoes a degenerative process characterized not just by fiber loss (sarcopenia) but by fatty infiltration, which functionally impairs contractile performance even when gross muscle size remains relatively preserved.

Key Findings

The study found that higher levels of thigh IMAT were associated with reduced muscle strength and diminished functional mobility, even when controlling for total muscle cross-sectional area. This dissociation is critical: an older adult might retain relatively large thigh muscles on a scan, yet perform poorly in strength and mobility tasks if those muscles are heavily infiltrated with fat.

Functional mobility — measured through tools such as the Timed Up and Go test or gait speed assessments — is a robust predictor of fall risk, hospitalization, and mortality in older populations. The finding that IMAT independently degrades these outcomes argues strongly for interventions targeting not just muscle volume but muscle quality.

Resistance training, particularly high-velocity power training, has shown promise in reducing IMAT and improving the ratio of contractile to non-contractile tissue within aging muscles. Nutritional strategies supporting muscle protein synthesis may further help preserve the architectural integrity of thigh musculature across the lifespan.

In older adults, thigh intermuscular adipose tissue independently predicts reduced muscle strength and functional mobility, highlighting that muscle quality — not just quantity — is essential for maintaining independence and preventing fall-related injury.

Connecting the Dots: A Unified Framework for Thigh Muscle Health

1. The Thigh Is Not Cosmetic — It Is Clinical

For decades, skeletal muscle was treated as a biomechanical structure — important for movement, secondary to “real” organs like the heart or liver. That hierarchy is no longer scientifically defensible. The quadriceps and hamstrings represent one of the largest reservoirs of metabolically active tissue in the human body. Their size and quality influence insulin sensitivity, inflammatory signaling, venous return, mitochondrial density, and functional biomechanics.

To ignore thigh muscle status in clinical practice is to overlook a central regulator of systemic physiology.

2. Rehabilitation Science Confirms a Mechanical–Neuromuscular Axis

Low back pain remains a leading cause of disability worldwide. Evidence now shows that targeted thigh muscle strengthening — even delivered through structured telerehabilitation — meaningfully improves outcomes in chronic low back pain populations.

This reinforces a key principle: proximal stability is not confined to the lumbar spine. Weakness in the anterior and posterior thigh musculature alters pelvic tilt, increases lumbar shear stress, and perpetuates pain cycles.

Strengthening the thigh is therefore not auxiliary therapy — it is foundational therapy.

3. Peripheral Muscle Influences Central Cardiovascular Capacity

In performance physiology, thigh muscle thickness correlates with VO₂ max and ventilatory efficiency in trained athletes. This is a powerful reminder that aerobic capacity is not solely a cardiac phenomenon.

Peripheral muscle mass enhances:

Capillary density

Mitochondrial content

Oxygen extraction capacity

Metabolic buffering during high-intensity efforts

The implication is profound: building thigh muscle may expand aerobic ceiling — not merely strength output.

4. The Thigh as a Metabolic Shield

Skeletal muscle accounts for the majority of insulin-mediated glucose uptake. Reduced thigh muscle mass compromises glucose disposal, amplifies hyperinsulinemia, and accelerates hepatic lipogenesis.

Population imaging data now demonstrate that lower thigh muscle mass independently associates with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) — even after adjusting for obesity.

This reframes resistance training as:

A liver-protective strategy

A metabolic disease intervention

A frontline therapy for insulin resistance

Muscle preservation is metabolic prevention.

5. Quality Matters More Than Size in Aging

In older adults, the infiltration of intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) predicts reduced strength and impaired mobility independent of cross-sectional area.

This distinction is critical. A muscle can appear large yet function poorly if infiltrated by fat. Muscle quality — contractile density, neuromuscular integrity, and power output — determines independence.

Functional mobility predicts:

Fall risk

Hospitalization

Mortality

Thus, preserving thigh muscle quality is synonymous with preserving autonomy.

6. A Lifespan Strategy, Not an Athletic Luxury

Thigh muscle health should not be relegated to athletes or rehabilitation clinics. It should be integrated into:

Preventive medicine

Metabolic disease management

Geriatric care

Performance optimization

Resistance training targeting the lower body, adequate protein intake, and periodic functional assessments represent low-cost, high-impact interventions with cross-system benefits.

7. The Paradigm Shift

We routinely screen blood pressure, lipids, and glucose. Perhaps it is time to screen muscle strength, muscle thickness, and muscle quality with similar seriousness.

The thigh is not merely a locomotor structure. It is:

A metabolic organ

A cardiovascular partner

A biomechanical stabilizer

A determinant of independence

The emerging evidence compels a reframing: muscle is medicine — and the thigh is one of its most powerful formulations.

Practical Implications: What You Can Do

Drawing on this evidence base, here are evidence-informed strategies for maintaining and improving thigh muscle health across different life stages and contexts:

For individuals with low back pain: Consider telerehabilitation programs specifically designed to strengthen the quadriceps and hamstrings. Research supports their efficacy and accessibility. Seek guidance from a licensed physiotherapist who can deliver a tailored remote program (Abdala et al., 2025).

For athletes and coaches: Incorporate regular ultrasound-based monitoring of thigh muscle thickness as part of performance assessment. Combined with cardiopulmonary exercise testing, this can provide a comprehensive picture of aerobic readiness (Komici et al., 2026).

For individuals managing metabolic health: Resistance training targeting large lower-body muscle groups — including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and adductors — may improve insulin sensitivity and reduce liver fat, serving as a valuable complement to dietary and pharmacological interventions (Osmancevic et al., 2025).

For older adults and their caregivers: Prioritize muscle quality alongside muscle quantity. Incorporate power training, adequate protein intake (especially leucine-rich sources), and regular functional mobility assessments. Identifying early IMAT accumulation through imaging may flag those at highest fall risk (Borghi et al., 2022).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does thigh muscle weakness contribute to low back pain?

Thigh muscles — particularly the quadriceps and hamstrings — play a critical role in stabilizing the pelvis and lumbar spine during movement. When these muscles are weak, the body compensates by overloading the lumbar erector spinae and facet joints, increasing compressive and shear forces on the lower spine. This compensation is a well-established mechanical pathway for the development and perpetuation of low back pain. Targeted strengthening of the thigh musculature can redistribute these forces and significantly reduce pain intensity and disability (Abdala et al., 2025).

Q2: Can telerehabilitation be as effective as in-person physical therapy for thigh muscle strengthening?

Based on the evidence from Abdala et al. (2025), telerehabilitation-based thigh muscle strengthening programs demonstrated meaningful effectiveness in volunteers with low back pain. While in-person therapy still offers advantages — particularly for hands-on manual therapy and real-time biomechanical correction — digital platforms provide an effective and accessible alternative for progressive resistance exercise delivery, particularly for populations with mobility limitations, geographic barriers, or time constraints.

Q3: Why would thigh muscle thickness relate to cardiorespiratory fitness in soccer players?

The relationship is likely multifactorial. Larger thigh muscle cross-sections have greater mitochondrial density and capillary supply, enhancing oxygen extraction from the blood. Additionally, greater peripheral muscle mass increases cardiac stroke volume demand during exercise, potentially driving beneficial cardiac adaptations over time. Komici et al. (2026) found that thigh muscle thickness correlated with both VO₂ max and ventilatory efficiency, suggesting that peripheral and central cardiovascular adaptations are closely coupled in trained athletes.

Q4: What is MASLD, and why is skeletal muscle important for liver health?

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the new nomenclature for what was previously called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. It involves excessive fat accumulation in liver cells and is driven largely by insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction. Skeletal muscle — especially in large, metabolically active regions like the thigh — is the body's principal site for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. When thigh muscle mass declines, glucose disposal efficiency drops, triggering compensatory hyperinsulinemia that drives hepatic de novo lipogenesis and fat deposition. Osmancevic et al. (2025) demonstrated this association directly, highlighting the thigh as a muscle group of particular metabolic relevance.

Q5: What is intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) and how does it differ from regular body fat?

Intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) is fat deposited between and within skeletal muscle fascicles, distinct from subcutaneous fat (beneath the skin) and visceral fat (surrounding internal organs). Unlike these depots, IMAT directly disrupts the force transmission within muscle and impairs contractile function by physically displacing contractile proteins and altering neuromuscular signaling. Borghi et al. (2022) demonstrated that elevated thigh IMAT was independently associated with lower muscle strength and reduced functional mobility in older adults, even when total muscle cross-sectional area was accounted for.

Q6: Is it possible to reduce thigh IMAT through exercise?

Yes. Research indicates that resistance training — particularly programs emphasizing higher velocities and functional movement patterns — can reduce intramuscular and intermuscular fat while simultaneously increasing lean muscle fiber volume. High-load resistance training stimulates muscle protein synthesis, promoting the replacement of non-contractile tissue with contractile elements. Aerobic exercise may further assist by improving overall metabolic flux and fat oxidation. Combined with adequate dietary protein intake, these strategies represent the most evidence-supported approaches to improving muscle quality in older adults (Borghi et al., 2022).

Q7: At what age should people start paying attention to thigh muscle quality?

While the dramatic consequences of muscle decline are most visible in older adults, the process of muscle fiber quality deterioration can begin as early as the fourth decade of life, particularly in sedentary individuals. Preventive attention to thigh musculature — through consistent resistance training, adequate protein consumption, and regular functional movement — is advisable from early adulthood. The earlier individuals establish these habits, the greater their muscle reserve heading into later life when age-related loss becomes more pronounced and the margin for functional decline is narrower

Author’s Note

As a physician trained in internal medicine and deeply engaged in reviewing emerging metabolic and exercise physiology research, I have long believed that skeletal muscle is one of the most underappreciated organs in clinical medicine. We routinely measure blood glucose, lipid profiles, liver enzymes, and cardiac biomarkers — yet we rarely assess muscle mass, muscle quality, or functional strength with the same seriousness, despite their profound systemic influence.

The studies discussed in this article reinforce a theme that has been consistently emerging in the scientific literature: thigh musculature is not merely mechanical tissue. It is a central regulator of metabolic health, a contributor to cardiorespiratory efficiency, a stabilizer in musculoskeletal pain syndromes, and a determinant of functional independence with aging. In many ways, the thigh serves as a clinical intersection point where rehabilitation medicine, hepatology, sports physiology, and gerontology converge.

My intention in synthesizing these findings is not to oversimplify complex pathophysiology, but to highlight an actionable and empowering truth: muscle is modifiable medicine. Unlike many risk factors that require pharmacologic intervention, skeletal muscle mass and quality respond robustly to targeted training, nutritional optimization, and structured rehabilitation strategies.

As research continues to evolve, I anticipate that routine assessment of muscle composition — particularly in the lower body — will become an integral part of preventive and therapeutic healthcare frameworks.

Until then, the evidence already speaks clearly: investing in your thigh muscles is an investment in systemic health, resilience, and longevity.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Before starting an exercise program, you must consult with a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions (such as cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or advanced metabolic disease). Exercise carries inherent risks, and you assume full responsibility for your actions. This article does not establish a doctor-patient relationship.

Related Articles

References

Abdala, D. W., Castro, T., Costa, W. D. S. D., Alves Silveira, B., Silva, G. J. A., Fonseca, N. D. S. M., Simão, A. P., & Carvalho, L. C. (2025). Effect of thigh muscle strength training through telerehabilitation in volunteers with low back pain: A controlled and randomized clinical trial. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 43, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2025.04.016

Borghi, S., Bonato, M., La Torre, A., Banfi, G., & Vitale, J. A. (2022). Interrelationship among thigh intermuscular adipose tissue, cross-sectional area, muscle strength, and functional mobility in older subjects. Medicine, 101(26), e29744. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029744

Komici, K., Parente, A., Di Trolio, R., et al. (2026). Associations of thigh muscle thickness with cardiorespiratory fitness and ventilatory efficiency in male soccer athletes. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-38770-7

Osmancevic, A., Gummesson, A., Allison, M., Kullberg, J., Li, Y., Bergström, G., & Daka, B. (2025). Thigh muscles and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Findings from the SCAPIS/IGT-Microbiota study. Liver International, 45(8), e70239. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.70239