The Metabolic Triad: Why Diabetes, Obesity & CVD Are One Epidemic

Explore 2025 research uncovering the complex link between diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Learn about the surprising 'Obesity Paradox' and why metabolic quality beats weight on the scale.

METABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

12/1/202517 min read

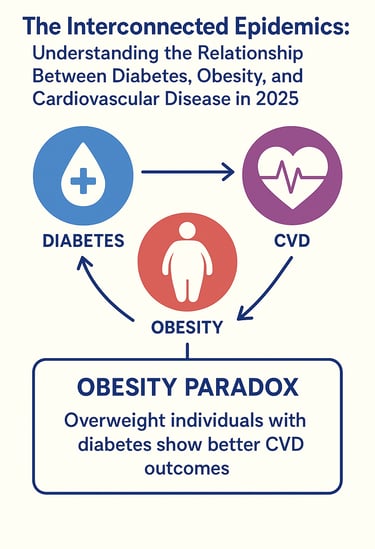

The global health landscape faces an unprecedented challenge: three interconnected epidemics that feed into one another like a cascade of dominoes. Diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are no longer isolated health conditions affecting separate populations—they're deeply intertwined metabolic disorders that amplify each other's impact. Recent 2025 research has begun to illuminate just how complex and intricate these relationships truly are, offering crucial insights into prevention and treatment strategies that could transform how we approach public health.

If you've ever wondered why your doctor seems concerned about your weight when discussing heart health, or why controlling blood sugar feels connected to managing cholesterol, you're tapping into something real. The latest evidence from groundbreaking cohort studies and genetic research reveals that these three conditions share common pathways, triggering mechanisms, and risk factors that demand a more integrated understanding of metabolic health.

Clinical Pearls

1. Metabolic Quality Trumps Weight in Cardiovascular Risk.

The Pearl: The Obesity Paradox reveals that once diabetes is established, high metabolic quality (preserved insulin sensitivity, low inflammation, high cardiovascular fitness) offers greater cardiac protection than low body weight alone.

Clinical Application: Prioritize interventions that improve fitness and metabolic markers over weight loss alone, especially in elderly or frail diabetic patients, as metabolic health is the primary determinant of long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

2. Insulin Resistance is the Shared Root Cause.

The Pearl: Diabetes, obesity, and CVD are not independent; they are manifestations of a common core dysfunction: Insulin Resistance. This mechanism drives excess fat storage, hyperglycemia, and the release of inflammatory molecules that directly damage blood vessels.

Clinical Application: All management plans must be integrated to target insulin sensitivity simultaneously, using strategies like consistent physical activity and specific medications that improve cellular insulin response.

3. Lifestyle Modification Produces Simultaneous, Independent Triumphs.

The Pearl: Comprehensive lifestyle interventions (dietary improvement, increased activity, better sleep) produce simultaneous and profound metabolic improvements across all three conditions, often independent of significant weight loss.

Clinical Application: Emphasize to patients that metabolic gains happen first. Encourage them to track non-weight markers (HbA1c, triglycerides, fitness level) as motivation, validating that their efforts are working even if the scale is slow to move.

4. Fitness is a Non-Negotiable Vascular Medicine.

The Pearl: Cardiovascular fitness provides critical physiological reserve and improves vascular function, making it a primary defense against adverse cardiac events in the context of diabetes and obesity.

Clinical Application: Prescribe regular, consistent movement—both aerobic and resistance training—as a core, foundational therapy, knowing that its vascular protective effects are essential regardless of the patient's BMI.

5. Central Adiposity Remains the Most Urgent Risk Marker.

The Pearl: While the overall BMI-risk relationship is complex (the paradox), central (visceral) adiposity is consistently implicated in the release of pathological inflammatory cytokines and remains the most reliable indicator of increased underlying cardiovascular risk.

Clinical Application: Always measure and monitor waist circumference and prioritize therapies (pharmacological or lifestyle) proven to reduce visceral fat stores, as this reduction directly addresses the most dangerous pro-inflammatory component of obesity.

The Growing Epidemic: By the Numbers

Before diving into the science, let's establish the scale of this global health crisis. Obesity affects approximately 2.6 billion people worldwide, making it one of the most prevalent health conditions of our time. Type 2 diabetes impacts over 400 million adults globally, with rates climbing annually. Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for approximately 17.9 million deaths annually.

But here's what makes this more alarming: these aren't three separate epidemics—they're interconnected manifestations of a common underlying metabolic dysfunction. When you have one, your risk of developing the others multiplies exponentially.

Understanding the Trinity: The Metabolic Triad

What Is This Connection?

The relationship between diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease operates through several shared biological mechanisms. At the heart of this interconnection lies insulin resistance—a condition where your body's cells don't respond properly to insulin, the hormone responsible for regulating blood sugar and fat metabolism.

Insulin resistance creates a perfect storm: blood sugar levels rise, eventually leading to type 2 diabetes; the body stores excess energy as fat, contributing to obesity; and excess fat tissue releases inflammatory molecules and impairs the function of blood vessels, directly promoting cardiovascular disease. This is why researchers increasingly refer to these conditions as components of metabolic syndrome or the cardiometabolic disease spectrum—they share common origins and pathways.

Key Breakthrough: The UK Biobank Cohort Study (2023)

One of the most comprehensive examinations of this relationship comes from a landmark study examining how diabetes phenotypes, obesity patterns, and cardiovascular disease presentations cluster together in real populations. The research analyzed data from over 400,000 individuals, providing unprecedented clarity on these interconnections (Brown et al., 2023).

What the study revealed: distinct patterns in how these conditions co-occur. Some individuals developed metabolically healthy obesity (where obesity existed without metabolic dysfunction), while others showed severe cardiometabolic complications despite relatively lower body weights. This finding is revolutionary because it challenges the one-size-fits-all approach to metabolic health.

The study's most significant takeaway? The combination of type 2 diabetes with central obesity (fat accumulation around the abdomen) created the highest risk for cardiovascular disease complications. Individuals with this specific phenotype showed a four-fold increase in adverse cardiovascular events compared to those without metabolic dysfunction.

Key Takeaway: The phenotype matters more than any single condition. Your specific pattern of obesity, glucose metabolism, and cardiovascular risk factors determines your health trajectory more than any isolated measurement.

The Interconnected Epidemics: 2025 Research Insights

Breaking Down the Causal Pathways

A significant 2025 study examined the epidemic nature of obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, emphasizing how these conditions represent interconnected epidemics rather than isolated health problems (Gupta et al., 2025). The epidemic concept is illuminating: just as infectious diseases spread through populations via transmission pathways, these metabolic diseases spread through shared mechanisms. One person's metabolic dysfunction doesn't cause another's directly, but the underlying drivers—sedentary lifestyles, ultra-processed food environments, chronic stress, and sleep disruption—create population-level epidemics.

This research identified several critical interconnection points:

Inflammation as a common pathway: Excess adipose tissue (fat tissue) doesn't just store energy—it actively produces inflammatory molecules called adipokines and cytokines. These inflammatory markers damage blood vessel linings, promote plaque formation in arteries, and impair insulin signaling. In essence, obesity creates chronic inflammation that drives both diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Lipid metabolism disruption: The research highlighted how dyslipidemia (abnormal blood fat levels) represents a common thread. Obesity leads to increased triglyceride production and reduced HDL cholesterol, which simultaneously worsens insulin resistance and accelerates atherosclerosis. This creates a vicious cycle: each condition amplifies the metabolic damage caused by the others.

Endothelial dysfunction: The cells lining blood vessels (the endothelium) depend on healthy metabolic signaling to function properly. Hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and insulin resistance directly damage these cells, while excess adiposity impairs the production of protective molecules like nitric oxide. The result? Blood vessels become stiffer, narrower, and more prone to clotting—the hallmark of cardiovascular disease.

Key Takeaway: These aren't diseases developing in isolation. They share inflammatory pathways, metabolic dysfunction, and vascular damage mechanisms that create a unified disease process affecting multiple organ systems.

Genetic Insights: The Mendelian Randomization Study

Perhaps the most sophisticated 2025 research comes from a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study examining causal relationships among seven cardiovascular-associated metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and various lipid disorders (Lai et al., 2025). Why this matters: Mendelian randomization uses genetic variations as natural experiments to determine whether observed associations between diseases reflect true causal relationships or are merely correlated. This approach sidesteps the confounding problems that plague traditional observational studies.

The causal cascade revealed: a directional flow of causation among these conditions. Obesity demonstrates causal effects on type 2 diabetes, which in turn causally influences cardiovascular disease risk. However, the relationships aren't purely unidirectional. Diabetes and dyslipidemia show bidirectional causal relationships, meaning each worsens the other in a feedback loop.

Perhaps most importantly, the research revealed that central obesity (measured by waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio) carries substantially higher causal impact on cardiovascular outcomes than general obesity alone. This distinction has profound implications for how clinicians assess risk and prioritize interventions.

Genetic predisposition landscape: The study identified shared genetic architecture among these conditions, suggesting that individuals inherit predispositions toward the entire metabolic disease spectrum rather than individual diseases. However—and this is crucial—genetic risk represents only one component. Environmental and behavioral factors remain paramount in determining disease manifestation.

Key Takeaway: The causal chain flows from obesity → diabetes → cardiovascular disease, with each condition amplifying subsequent risks. However, waist circumference and central fat distribution matter more than total body weight in determining cardiovascular outcomes.

The Obesity Paradox: Complexity in Clinical Practice

Recent 2025 research has brought renewed attention to the "obesity paradox"—a counterintuitive observation that some overweight or moderately obese individuals with cardiovascular disease may exhibit better outcomes than those with normal weight (Thakker et al., 2025). This paradox is particularly intriguing in patients with type 2 diabetes, where obesity is a well-established risk factor for cardiometabolic complications.

However, emerging evidence suggests this paradox requires careful interpretation. Multiple confounding factors influence these observations, including reverse causality, differences in risk factor profiles, and adipose tissue distribution. Critically, recent mechanistic research indicates that what appears protective may reflect differences in metabolic health status rather than true protective effects of obesity itself. Advanced body composition analysis reveals that the distinction between visceral and subcutaneous fat distribution, muscle mass, and metabolic phenotype matters far more than BMI alone in determining cardiovascular outcomes.

The implications are significant: the apparent protective effect of higher BMI in some populations likely reflects bias in how obesity is measured and classified. When more sophisticated assessments account for metabolic health status and fat distribution, the protective effect diminishes substantially. This underscores why integrated metabolic assessment—not just weight measurement—is essential for accurate risk stratification.

The Biological Mechanisms Connecting These Epidemics

Insulin Resistance: The Central Hub

Insulin resistance functions as the central switching point where obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease converge. When cells don't respond appropriately to insulin signals, the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin (hyperinsulinemia). This excess insulin triggers a cascade of metabolic consequences: excessive insulin stimulates fat storage, particularly in visceral (abdominal) locations, driving central obesity; increases sodium reabsorption in kidneys, raising blood pressure; promotes the liver's production of triglycerides and VLDL cholesterol particles, creating dyslipidemia; and impairs vascular function, reducing nitric oxide availability and increasing arterial stiffness.

This is why managing insulin resistance has become the cornerstone of integrated cardiometabolic disease prevention. Unlike treating diabetes with medication or obesity with diet alone, addressing insulin resistance simultaneously improves all three conditions.

Adipose Tissue Dysfunction

Not all fat is created equal. The 2025 research emphasizes that adipose tissue functions as an endocrine organ—it produces hormones and signaling molecules that regulate metabolic health throughout the body. In obesity, adipose tissue becomes dysfunctional: it produces excessive inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1), which increase systemic inflammation; reduces secretion of adiponectin, a protective hormone that normally improves insulin sensitivity and vascular function; develops hypoxia (low oxygen levels) due to limited blood supply, further triggering inflammatory responses; and becomes infiltrated with immune cells that amplify the inflammatory state.

This dysfunctional adipose tissue simultaneously worsens insulin resistance, accelerates pancreatic beta-cell failure (driving diabetes), and promotes atherosclerosis through inflammatory mechanisms.

The Vascular Connection

Recent research has illuminated how obesity and diabetes directly damage blood vessels through multiple mechanisms. Endothelial dysfunction represents the earliest detectable vascular injury. High blood sugar levels impair the production of nitric oxide, a crucial molecule that keeps blood vessels relaxed and prevents clotting. High insulin levels paradoxically reduce this protective effect. Excess circulating lipids promote oxidative stress in the endothelium, triggering inflammation and cell death.

These changes create the perfect environment for atherosclerosis—the gradual buildup of plaque in arteries. The combination of dyslipidemia, endothelial dysfunction, and systemic inflammation seen in individuals with obesity and diabetes accelerates this process dramatically.

Key Takeaway: The vascular damage in cardiovascular disease doesn't begin at the time of heart attack or stroke—it starts years earlier when insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction begin injuring blood vessel linings.

Why Current Single-Disease Approaches Fall Short

The Limitations of Siloed Treatment

Traditionally, healthcare has treated type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease as separate medical problems managed by different specialists. This fragmented approach misses the fundamental truth revealed by 2025 research: these are expressions of a common underlying metabolic disease process. A patient might see an endocrinologist for diabetes, a cardiologist for hypertension, and a gastroenterologist for weight management—each prescribing medications and lifestyle changes in isolation. However, without addressing the common mechanism of insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction, each intervention has limited effectiveness.

The Evidence for Integration

Recent research demonstrates that individuals addressing the entire metabolic phenotype—not just individual conditions—show superior outcomes across all three disease areas. Those who improved insulin sensitivity, reduced central obesity, and normalized lipid profiles simultaneously saw improvements in blood sugar control, blood pressure, and cardiovascular function. This integrated approach isn't just theoretically sound—it's pragmatically necessary. Many medications used to treat one condition worsen others. Traditional diabetes medications, for instance, often promote weight gain and worsen cardiovascular risk. Conversely, interventions that address metabolic dysfunction holistically tend to improve all three conditions simultaneously.

Prevention and Management Strategies: An Integrated Approach

Dietary Interventions for Metabolic Health

The foundation of managing the obesity-diabetes-cardiovascular disease continuum remains dietary modification. However, not all diets are equally effective for addressing underlying metabolic dysfunction. The Mediterranean diet and low-glycemic-index diets have shown consistent benefits for improving insulin sensitivity, reducing central obesity, and lowering cardiovascular risk markers. These diets emphasize whole foods, fiber-rich carbohydrates, healthy fats, and lean proteins—addressing all three components of the metabolic triad simultaneously.

Limiting ultra-processed foods deserves special emphasis. The 2025 research highlighted how highly processed foods trigger rapid blood sugar spikes, promote excessive calorie intake, and contain additives that increase systemic inflammation. Replacing these with whole, minimally processed alternatives represents one of the most impactful modifications.

Physical Activity: The Metabolic Transformer

Exercise represents perhaps the most powerful intervention for addressing insulin resistance and the interconnected epidemics. Exercise improves insulin sensitivity through multiple mechanisms independent of weight loss. It increases glucose uptake by muscles, reduces visceral fat more efficiently than other interventions, and reduces systemic inflammation. The 2025 research emphasizes resistance training alongside aerobic activity. While aerobic exercise improves cardiovascular function and burns calories, resistance training builds muscle mass, which actively contributes to improved metabolic health by increasing glucose uptake and reducing insulin resistance.

Practical recommendation: 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly combined with 2-3 days of resistance training provides optimal benefits for the metabolic disease spectrum.

Weight Management: Beyond the Scale and Lifestyle Modification Impact

While weight loss remains important, the 2025 research clarifies that weight loss itself isn't the primary goal—metabolic improvement is. Some individuals achieve substantial metabolic benefits with modest weight reductions (5-10%), while others show minimal improvement despite significant weight loss. This distinction matters profoundly.

Recent research emphasizes that lifestyle modification substantially impacts multiple cardiometabolic markers independent of weight change alone. Improvements in insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and lipid profiles can precede visible weight changes, and more importantly, structured interventions addressing metabolic dysfunction show superior outcomes compared to traditional calorie-restriction approaches. Emerging pharmacological interventions targeting insulin resistance and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) signaling have demonstrated remarkable effects on weight, blood sugar, and cardiovascular outcomes when combined with lifestyle modifications.

Sleep and Stress Management

Often overlooked, sleep deprivation and chronic stress directly impair metabolic function. Poor sleep worsens insulin resistance, promotes weight gain (particularly in the abdomen), increases inflammatory markers, and raises cardiovascular disease risk. The 2025 research underscores that integrated metabolic health management must address these factors. Seven to nine hours of consistent, quality sleep should be considered as important as diet and exercise for managing the obesity-diabetes-cardiovascular disease continuum.

Real-World Impact: What This Means for You

Your Individual Risk Assessment

Understanding your position within the metabolic disease spectrum requires looking beyond single measurements. Your healthcare team should evaluate insulin levels and glucose tolerance (fasting glucose, HbA1c, insulin resistance indices); body composition and fat distribution (not just BMI, but particularly waist circumference); lipid profiles (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides—especially triglyceride-to-HDL ratios); blood pressure and vascular markers (arterial stiffness, endothelial function if available); inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, IL-6); and lifestyle factors (diet quality, physical activity, sleep quality, stress levels).

This comprehensive assessment reveals your specific cardiometabolic phenotype—which conditions pose greatest risk for you individually and which interventions merit priority.

The Timeline of Metabolic Disease

Understanding disease progression matters because it emphasizes the critical window for intervention. Metabolic disease typically develops through recognizable stages:

Stage 1: Metabolic dysfunction occurs silently, with impaired fasting glucose, elevated triglycerides, and emerging insulin resistance present, yet the individual often feels fine.

Stage 2: Clinical disease emergence. Type 2 diabetes develops, or blood pressure creeps into hypertensive range, or LDL cholesterol rises despite weight stability.

Stage 3: Complications manifest. Cardiovascular events occur, diabetic complications emerge, or significant metabolic decompensation requires intensive intervention.

The 2025 research emphasizes that intervention at Stage 1—when only metabolic dysfunction exists without clinical disease—offers tremendous opportunity. Aggressive lifestyle modification or pharmacological intervention at this stage can prevent progression.

Key Takeaways: Essential Points to Remember

Diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease aren't separate epidemics—they represent interconnected expressions of common metabolic dysfunction. Understanding their shared mechanisms enables more effective prevention and management.

Insulin resistance serves as the central mechanism linking all three conditions. Addressing insulin resistance improves all three simultaneously, making it the logical priority for intervention.

The phenotype matters more than any single measurement. Your specific pattern of central obesity, metabolic dysfunction, and cardiovascular risk determines your health trajectory more than isolated values.

Central obesity carries disproportionate metabolic impact. Fat accumulation around the abdomen drives metabolic disease more severely than general body weight, making measurement of waist circumference critical for risk assessment.

Genetic predisposition isn't destiny. While genetic factors influence metabolic disease risk, environmental and behavioral factors remain paramount in determining disease manifestation.

Integrated approaches addressing the entire metabolic phenotype outperform single-disease interventions. Simultaneously addressing insulin resistance, adipose tissue dysfunction, and vascular damage yields superior outcomes.

The obesity paradox requires careful interpretation. What appears protective often reflects differences in metabolic phenotype rather than true protective effects of obesity itself.

The timeline for intervention matters critically. Metabolic dysfunction provides a window where aggressive intervention can prevent disease progression.

Traditional single-disease approaches miss the fundamental biology. Fragmented care by different specialists managing individual conditions independently reduces intervention effectiveness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: If I'm overweight but "metabolically healthy," should I still try to lose weight?

A: The concept of "metabolically healthy obesity" exists but remains relatively uncommon. More importantly, maintaining metabolic health typically requires sustained attention to the factors that keep you metabolically healthy—diet quality, physical activity, and weight stability. While modest weight gain might not immediately trigger metabolic dysfunction in some individuals, it often accelerates the underlying metabolic decline that precedes overt disease. Rather than focusing solely on weight loss, prioritize maintaining the insulin sensitivity and metabolic function that keeps you healthy.

Q: Can I have diabetes without obesity? Can I have obesity without metabolic dysfunction?

A: Both scenarios occur, but understanding why matters. Some individuals develop type 2 diabetes through severe beta-cell failure with relatively modest weight gain, while others achieve relatively normal body weights despite significant metabolic dysfunction. More commonly, type 2 diabetes co-occurs with central obesity. Research has identified individuals with metabolically healthy obesity, though they remain a minority. However, the 2025 research suggests that metabolically healthy obesity represents a transient state rather than a stable phenotype—most individuals eventually transition to metabolically unhealthy obesity over time.

Q: How quickly can I improve my metabolic health with lifestyle changes?

A: Changes occur faster than many realize. Insulin sensitivity improves within days to weeks of dietary modification and increased physical activity, often before measurable weight loss. Blood glucose control can improve within weeks. Inflammatory markers decline within months. Vascular function improvements may require 3-6 months to fully develop. This means you'll experience health improvements even before the scale shows significant changes—a powerful motivator for continuing lifestyle modifications.

Q: Are medications necessary for managing metabolic disease, or can lifestyle changes suffice?

A: This depends on individual circumstances. Some individuals achieve excellent metabolic control through lifestyle modifications alone, while others require pharmacological support to achieve adequate control. Recent evidence suggests that combining lifestyle interventions with targeted medications addressing insulin resistance or metabolic dysfunction yields superior outcomes compared to either approach in isolation. Your healthcare provider should assess your individual situation and recommend the approach most likely to achieve your metabolic goals.

Q: Does the order matter? Should I address diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular risk simultaneously or sequentially?

A: The integrated approach addressing all three simultaneously outperforms sequential intervention. Many patients attempt to lose weight first, then address blood sugar, then tackle cardiovascular risk—a fragmented timeline that extends disease duration and increases complication risk. Instead, interventions addressing insulin resistance simultaneously improve weight, blood glucose, and cardiovascular markers. This integrated approach proves more effective and sustainable.

Q: What role does genetics play? If my parents have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or obesity, am I destined to develop them too?

A: Genetics influences risk but doesn't determine destiny. The 2025 Mendelian randomization research identified shared genetic architecture among these conditions, indicating inherited predisposition toward the entire metabolic disease spectrum. However, genetic risk represents only one component—environmental factors, lifestyle choices, diet quality, and stress management remain paramount. Individuals with strong family histories benefit most from aggressive prevention strategies but absolutely can maintain metabolic health through conscious effort.

Q: How do I know if I have metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance?

A: Metabolic dysfunction exists on a spectrum rather than a binary yes/no state. Indicators include central obesity (waist circumference > 35 inches for women, > 40 inches for men), elevated fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dL), elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL), reduced HDL cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and elevated inflammatory markers. If you have three or more of these criteria, consult your healthcare provider about insulin resistance screening and metabolic assessment. However, don't wait for obvious abnormalities—subtle metabolic dysfunction exists on a spectrum, and early intervention prevents progression.

What to Do Next: Your Action Plan

The 2025 research on the interconnection between diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease provides unprecedented clarity—but clarity matters only when translated into action.

Immediate Steps (This Week)

Schedule a comprehensive metabolic assessment with your healthcare provider. Rather than accepting single measurements, request evaluation of your complete metabolic phenotype: glucose metabolism, lipid profiles, blood pressure, inflammatory markers, and body composition. Ask specifically about your insulin resistance status and whether your current healthcare approach addresses the interconnected nature of these conditions.

Assess your current lifestyle. Honestly evaluate your diet quality, physical activity level, sleep duration, and stress management. Identify one area where meaningful change would be most feasible—perhaps replacing ultra-processed foods, adding 30 minutes of walking daily, or improving sleep consistency.

Short-Term Changes (Next Month)

Implement one significant dietary modification. Rather than overhauling everything simultaneously, choose one meaningful change: reducing sugar-sweetened beverages, adding more whole foods, or eliminating the most processed items in your diet. Small, sustainable changes outperform dramatic overhauls that prove unsustainable.

Establish a movement practice. This needn't be intense exercise—consistent walking, swimming, or activities you enjoy work effectively. Aim for daily movement, combining aerobic activity with resistance training if possible.

Optimize sleep. Consistent sleep schedules, reduced screen time before bed, and creating a sleep-conducive environment address a critical but often-neglected metabolic factor.

Medium-Term Strategy (3-6 Months)

Track metabolic improvements beyond the scale. Request repeat testing of fasting glucose, HbA1c, triglycerides, blood pressure, and inflammatory markers to demonstrate metabolic improvements independent of weight changes. This reinforces progress and maintains motivation.

Deepen lifestyle changes. After establishing foundational habits, build gradually: increase physical activity duration or intensity, expand dietary improvements, or address stress management more systematically.

Consider working with integrated healthcare providers who address the entire metabolic disease spectrum rather than isolated conditions. Specialists in preventive cardiology, metabolic medicine, or lifestyle medicine increasingly understand these interconnections better than traditionally trained specialists.

Conclusion: A New Understanding, a New Approach

The 2025 research on diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease reveals what increasingly seems obvious: these aren't three separate epidemics but interconnected manifestations of common metabolic dysfunction. From the large-scale insights of the UK Biobank cohort study to the genetic clarity provided by Mendelian randomization research, the evidence converges on a simple yet profound truth: these conditions share origins, mechanisms, and—most importantly—solutions.

The metabolic triad develops through recognizable stages, driven by insulin resistance, adipose tissue dysfunction, and vascular damage—mechanisms susceptible to intervention at every level. The individuals who achieve optimal health aren't those who address diabetes alone, lose weight in isolation, or focus exclusively on cardiovascular protection. Instead, they're those who understand these conditions as connected expressions of metabolic disease and pursue integrated approaches addressing the underlying dysfunction.

Your genetics influence your starting point but don't determine your destination. Environmental factors, lifestyle choices, dietary patterns, and behavioral modifications remain powerful determinants of your metabolic future. The research validates what many have intuited: treating yourself as a whole person with integrated metabolic health needs yields better results than fragmenting yourself among specialists addressing isolated conditions.

The critical period is now. Whether you're experiencing early metabolic dysfunction, managing one or more of these conditions, or seeking to prevent their development, the science shows that integrated approaches addressing insulin resistance and the entire cardiometabolic phenotype work. The question isn't whether intervention helps—it clearly does. The only question remaining is whether you'll take action.

Your metabolic health represents one of the most valuable investments you can make. Begin today.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

The BMI Paradox: Why "Normal Weight" People Still Get High Blood Pressure | DR T S DIDWAL

How Insulin Resistance Accelerates Cardiovascular Aging | DR T S DIDWAL

The Metabolic Triad: Why Diabetes, Obesity & CVD Are One Epidemic | DR T S DIDWAL

What’s New in the 2025 Blood Pressure Guidelines? A Complete Scientific Breakdown | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Brown, O. I., Drozd, M., McGowan, H., Giannoudi, M., Conning-Rowland, M., Gierula, J., Straw, S., Wheatcroft, S. B., Bridge, K., Roberts, L. D., Levelt, E., Ajjan, R., Griffin, K. J., Bailey, M. A., Kearney, M. T., & Cubbon, R. M. (2023). Relationship among diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease phenotypes: A UK Biobank cohort study. Diabetes Care, 46(8), 1531–1540. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-0294

Gupta, A., Shah, K., & Gupta, V. (2025). Interconnected epidemics: Obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases—Insights from research and prevention strategies. Discovery in Public Health, 22, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-025-00496-8

Lai, Z., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Jiang, X., Yang, Y., Fan, X., Shi, Y., & Li, X. (2025). Causal relationships among seven cardiovascular-associated metabolic diseases: Insights from a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Metabolic Target Organ Damage, 5, 30. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/mtod.2025.20

Seth, C., Schmid, V., Mueller, S., Haykowsky, M., Foulkes, S. J., Halle, M., & Wernhart, S. (2025). Diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease—What is the impact of lifestyle modification? Herz, 50(4), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-025-05309-x

Thakker, J., Khaliq, I., Ardeshna, N. S., Lavie, C. J., & Oktay, A. A. (2025). The obesity paradox of cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus. Current Diabetes Reports, 25(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-025-01592-4