Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Core Driver of Aging and How Exercise Reverses It

Discover the science of mitochondrial aging, from ROS and mtDNA damage to NAD+ depletion. Learn how combining resistance and aerobic exercise is the proven therapeutic breakthrough to restore cellular energy and fight age-related disease.

AGING

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

12/14/202513 min read

Your cells contain tiny powerhouses called mitochondria that generate the energy your body needs to function. But here's the concerning reality: as you age, these vital organelles gradually deteriorate, triggering a cascade of age-related diseases from heart conditions to cognitive decline. Recent research published in 2024-2025 reveals that mitochondrial dysfunction isn't just a side effect of aging—it's a fundamental driver of the aging process itself.

This comprehensive guide explores the latest scientific evidence on mitochondrial aging, synthesizing breakthrough research to help you understand what's happening at the cellular level and what can actually be done about it.

Clinical Pearls

1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction is a Driver, Not Just a Consequence, of Aging ("The Central Role"):

Pearl: Mitochondrial dysfunction is a fundamental mechanism of aging ("The Vicious Cycle"), directly linking to the onset and progression of multiple age-related disorders (cardiovascular, diabetes, neurodegeneration) through increased Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations. Addressing mitochondrial health is therefore a primary strategy for increasing healthspan, not just treating symptoms. (Somasundaram et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2025)

2. Exercise is the Master Regulator for Mitochondrial Quality Control ("The Gold Standard Intervention"):

Pearl: Regular physical activity is the most powerful intervention, working better than single-target pharmaceuticals because it simultaneously activates PGC-1 alpha (driving mitochondrial biogenesis—making new mitochondria) and enhances mitophagy (quality control—removing damaged ones). This dual action reverses age-related decline in muscle and heart tissue more comprehensively than any single drug. (Bishop et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2025)

3. The Optimal Exercise Prescription is Combination Therapy ("Dual Modality Benefit"):

Pearl: For maximal mitochondrial benefit, neither aerobic nor resistance exercise is sufficient alone. Resistance training primarily stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis (creation and capacity), while aerobic exercise enhances mitochondrial oxidative efficiency. The optimal prescription is a combination: 2-3 weekly resistance sessions + 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity. (Zhang et al., 2025)

4. NAD+ Depletion is a Major Therapeutic Target ("The Energy Coenzyme"):

Pearl: The age-related decline in NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) impairs essential protective pathways, including DNA repair via sirtuins. Restoring NAD+ levels (e.g., through compounds like NMN or NR) shows clinical promise by reactivating these ancient cellular defense mechanisms, thereby improving muscle strength and reducing oxidative stress markers. (Jia et al., 2025)

5. Inflammation (Inflammaging) is Mitochondrial-Derived ("The NLRP3 Connection"):

Pearl: Dysfunctional mitochondria trigger chronic, low-grade, systemic inflammation (termed "inflammaging"). Damaged mitochondria release molecular debris (like mtDNA fragments and cardiolipin) that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, an alarm system. This continuous inflammatory signal is a major accelerator of aging and age-related disease, linking mitochondrial health directly to immune and inflammatory status.

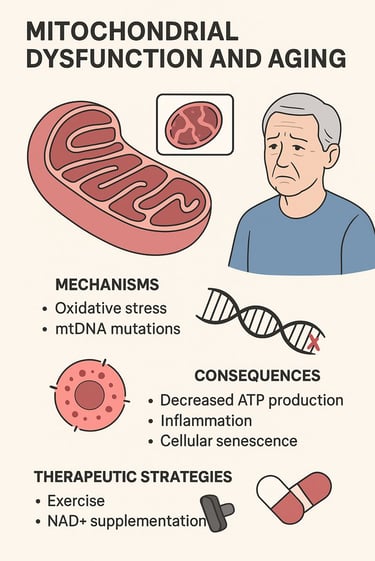

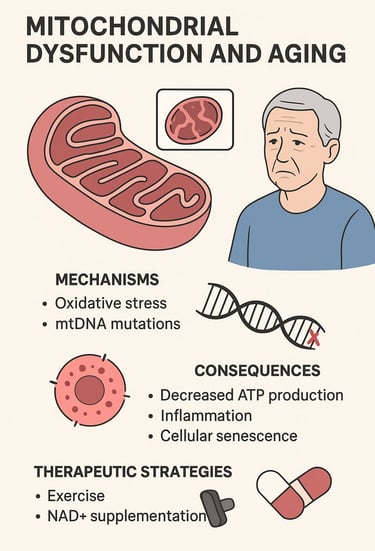

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Aging: Mechanisms, Consequences, and Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Section 1: Understanding Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Aging

What Exactly Is Mitochondrial Dysfunction?

Mitochondrial dysfunction refers to the progressive deterioration of mitochondrial structure and function that occurs naturally with advancing age. These energy-producing organelles, often called the "powerhouses of the cell," become increasingly inefficient at generating ATP (adenosine triphosphate)—the molecular currency of cellular energy.

According to recent research, mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with age-related disorders represents one of the most significant areas of gerontological research (Somasundaram et al., 2024). Their comprehensive analysis demonstrates that mitochondrial impairment correlates directly with the development of multiple age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndrome.

The Molecular Mechanisms Behind Mitochondrial Aging

The deterioration of mitochondria occurs through several interconnected mechanisms:

Oxidative Stress and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Accumulation

The primary culprit in mitochondrial aging is the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). During normal oxidative phosphorylation—the process by which mitochondria generate ATP—electrons occasionally leak from the electron transport chain, creating highly reactive molecules that damage cellular components. As detailed in recent research, this ROS-induced damage initiates a vicious cycle (Xu et al., 2025). The more damage accumulates, the more ROS is generated, accelerating the aging process itself.

This research emphasizes that oxidative stress doesn't just damage mitochondrial proteins and lipids—it also mutates mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA lacks the protective histone proteins and possesses less efficient repair mechanisms, making it particularly vulnerable to damage.

Mitochondrial DNA Mutations and Accumulation

The accumulation of mtDNA mutations represents a critical mechanism of aging. As these mutations build up, particularly in post-mitotic tissues like muscle and brain, they impair the synthesis of essential respiratory chain components. This creates a downward spiral: dysfunctional mitochondria produce more ROS, which cause more mutations, leading to further dysfunction.

Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics

Healthy mitochondria constantly undergo fusion and fission—processes that allow them to repair themselves and eliminate damaged sections. With age, this delicate balance deteriorates. The machinery responsible for these processes becomes less efficient, and more importantly, the autophagy system—the cellular cleanup crew—fails to remove damaged mitochondria promptly. This accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria significantly contributes to cellular aging.

Calcium Dysregulation and Mitochondrial Permeability Transition

Mitochondria play a crucial role in regulating cellular calcium, which is essential for proper cell signaling. In aging, this regulation becomes dysregulated, causing excessive calcium to accumulate inside mitochondria. This triggers opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, leading to loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, energy depletion, and ultimately cell death (Somasundaram et al., 2024).

NAD+ Depletion

One of the most significant discoveries in aging research is the progressive decline of NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) with age. This critical coenzyme powers numerous essential processes, including DNA repair through sirtuins and PARP (poly-ADP-ribose polymerase). NAD+ depletion literally weakens your cells' ability to defend themselves against damage (Jia et al., 2025).

Section 2: The Real-World Consequences of Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Understanding the mechanisms is important, but the consequences are what matter for your health.

Cellular-Level Consequences

When mitochondrial function declines, the most immediate consequence is reduced ATP production. This is particularly devastating for tissues with high metabolic demands: your brain uses approximately 20% of your body's energy despite comprising only 2% of body mass, your heart beats continuously throughout life, and your skeletal muscles require enormous energy during contraction and protein synthesis.

Impaired ATP generation means these tissues receive insufficient energy to maintain their normal functions, leading to weakness, cognitive decline, and cardiac dysfunction.

Inflammation and Inflammaging

Beyond simple energy depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction triggers chronic inflammation—what researchers call "inflammaging". Damaged mitochondria release molecules like cardiolipin and mtDNA fragments that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, a cellular alarm system. This constant low-grade inflammation accelerates aging throughout the body, contributing to multiple age-related diseases simultaneously.

Tissue-Level Manifestations

Sarcopenia and Muscle Weakness

One of the most visible consequences of mitochondrial dysfunction is sarcopenia—the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength. Declining mitochondrial biogenesis (the creation of new mitochondria) combined with impaired mitochondrial quality control drives progressive muscle deterioration (Zhang et al., 2025). This doesn't just mean weakness; it increases fall risk, reduces independence, and accelerates overall decline.

Neurodegeneration

The brain's enormous energy demands make it particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction. Impaired mitochondrial calcium handling, excessive ROS production, and reduced ATP availability all contribute to neurodegeneration. This manifests as cognitive decline, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions.

Metabolic Dysregulation

Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs your ability to regulate blood sugar and fat metabolism. This contributes directly to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome—conditions increasingly common with age.

Cellular Senescence

Perhaps most significantly, dysfunctional mitochondria trigger senescence—cells enter a state where they stop dividing but remain metabolically active. These senescent cells secrete pro-inflammatory molecules that damage neighboring healthy cells, accelerating tissue aging. This represents a vicious cycle where mitochondrial dysfunction causes cellular senescence, which further increases inflammation and ROS production.

Section 3: Therapeutic Strategies Emerging from Recent Research

The encouraging news is that mitochondrial dysfunction isn't inevitably irreversible. Multiple therapeutic approaches show promise in reversing or slowing mitochondrial aging.

Pharmacological Interventions

NAD+ Boosting Compounds

Perhaps the most studied therapeutic approach involves restoring NAD+ levels. Compounds like nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) can dramatically improve mitochondrial function. These molecules work by restoring NAD+ pools, which reactivates sirtuins (cellular aging clocks) and enhances NAD+-dependent repair mechanisms (Jia et al., 2025).

Clinical trials have demonstrated that NAD+ boosters improve muscle strength, enhance mitochondrial ATP production, and reduce markers of oxidative stress in aging individuals.

Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidants

Traditional antioxidants often fail because they can't effectively penetrate mitochondrial membranes where ROS damage occurs. Innovative mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants like MitoQ and SkQ1 solve this problem by attaching a positively charged molecule that concentrates them inside mitochondria. Early evidence suggests these compounds significantly reduce ROS-induced mitochondrial damage and improve energy production.

Polyphenols and Sirtuin Activators

Natural compounds like resveratrol activate sirtuins and AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase), triggering mitochondrial biogenesis—the creation of new, healthy mitochondria. These compounds essentially tell your cells: "Make more functional mitochondria." This approach addresses the problem at its root rather than just treating symptoms.

Enhancing Cellular Cleanup: Mitophagy

Mitophagy—the selective removal of damaged mitochondria through autophagy—becomes increasingly impaired with age. Therapeutic strategies to enhance mitochondrial quality control show tremendous promise. Compounds that activate PINK1/Parkin pathway signaling can identify and remove dysfunctional mitochondria more efficiently, preventing accumulation of damaged organelles.

Mitochondrial Dynamics Modulation

Rather than simply removing damaged mitochondria, researchers are developing strategies to optimize mitochondrial fusion and fission dynamics. Promoting fusion preserves functional capacity by mixing components from multiple mitochondria, while selective fission isolates and removes damaged sections. This "quality control through dynamics" approach represents an elegant therapeutic strategy under active development.

Section 4: Exercise as Mitochondrial Medicine—A Game-Changer

Recent research reveals that exercise may be the single most powerful therapeutic intervention for mitochondrial dysfunction—and it works through multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

How Exercise Restores Mitochondrial Function

Recent research presents groundbreaking work demonstrating that properly designed exercise programs trigger profound mitochondrial adaptations that essentially reverse many age-related changes (Bishop et al., 2025).

Stimulating Mitochondrial Biogenesis

The most powerful effect of exercise is activation of PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha)—a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. During exercise, muscle cells detect energy depletion, which activates AMPK and signaling cascades that induce PGC-1α expression. This transcription factor essentially commands your cells: "Build new mitochondria." Over weeks and months, individuals who exercise regularly develop substantially more mitochondria in their muscle cells, restoring energy production capacity (Zhang et al., 2025).

Improving Mitochondrial Quality Control

Exercise doesn't just create new mitochondria—it simultaneously improves the systems that remove damaged ones. Exercise activates autophagy and specifically mitochondrial quality control mechanisms, allowing cells to eliminate dysfunctional organelles efficiently while preserving healthy ones. This dual action—simultaneously creating new mitochondria while removing damaged ones—explains exercise's remarkable anti-aging effects.

Reducing ROS-Induced Damage

While exercise initially increases ROS production during the activity itself, this stimulates adaptive responses that increase antioxidant enzyme expression, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. These endogenous antioxidants provide superior protection compared to taking antioxidant supplements because they're produced exactly where needed and in appropriate quantities.

Enhancing NAD+ Metabolism

Resistance exercise and endurance training both activate NAD+-dependent pathways, increasing NAD+ availability and activating sirtuins. This creates a synergistic effect where exercise benefits are amplified by restoration of these crucial aging-clock regulators.

The Optimal Exercise Prescription for Mitochondrial Health

Zhang and colleagues (2025) emphasize in "Exercise-mediated regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in aging muscle" that both resistance training and endurance exercise drive mitochondrial adaptations, but through somewhat different mechanisms. Resistance training primarily stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and improves muscle protein synthesis, while endurance exercise enhances mitochondrial oxidative capacity and efficiency (Zhang et al., 2025).

The evidence suggests an optimal approach combines both modalities: resistance training 2-3 times weekly to build mitochondrial capacity and muscle mass, plus 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise weekly to enhance mitochondrial oxidative efficiency.

Why Exercise Works Better Than Pills

Research shows why exercise produces more comprehensive improvements than any single pharmacological intervention. Exercise simultaneously triggers multiple beneficial pathways: mitochondrial biogenesis, improved mitochondrial dynamics, enhanced quality control, reduced inflammation, improved insulin sensitivity, and activation of NAD+-dependent pathways (Memme et al., 2021).

Perhaps most importantly, exercise appears to work across all tissues. While pharmaceutical interventions might improve mitochondrial function in one organ, exercise benefits your brain, heart, muscles, and metabolic tissues simultaneously. This systems-level approach explains why regular physical activity remains the single most powerful anti-aging intervention available.

Exercise and Metabolic Disease Prevention

Regular physical activity specifically addresses the metabolic consequences of aging. Research shows that individuals who maintain regular exercise preserve insulin sensitivity, maintain healthy body weight, and avoid the metabolic dysfunction that typically develops with age—all through restoration of mitochondrial function (Jia et al., 2023).

Section 5: Precision Medicine and Personalized Approaches

The future of treating mitochondrial dysfunction lies in precision medicine. Research recognizes that individuals vary tremendously in their mitochondrial function, genetic susceptibility to mitochondrial disease, and response to interventions (Jia et al., 2025).

Assessing Individual Mitochondrial Function

Advanced diagnostics can now measure mitochondrial function through biomarkers including lactate levels, NAD+/NADH ratios, circulating mitochondrial DNA fragments, and specialized imaging of mitochondrial structure. These assessments allow personalized determination of which therapeutic approaches would be most beneficial for each individual.

Genetic and Epigenetic Considerations

Genetic variations affecting mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative stress response, and sirtuin function influence how individuals respond to interventions. Future therapeutic approaches will account for these individual differences, recommending specific exercise protocols, pharmaceutical combinations, and lifestyle modifications based on genetic profiles.

Combination Therapeutic Approaches

Rather than relying on single interventions, precision medicine combines multiple approaches synergistically. For example, someone with severe mitochondrial dysfunction might receive NAD+ boosters to restore sirtuin function, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants to reduce ROS damage, while simultaneously implementing a structured exercise program to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis.

Section 6: Emerging Therapies and Future Directions

Gene and Stem Cell Therapies

Although earlier in development than pharmacological approaches, gene therapy targeting mtDNA mutations and stem cell approaches to replace dysfunctional mitochondria represent exciting future possibilities. Researchers are developing techniques to selectively eliminate mutant mtDNA (a process called heteroplasmy shifting) while preserving normal mtDNA.

Senolytic Medications

Senolytic drugs—medications that selectively eliminate senescent cells—represent another emerging approach. By removing senescent cells that accumulate with age and secrete pro-inflammatory molecules, senolytic compounds may reduce the inflammatory burden driven by dysfunctional mitochondria.

Mitochondrial Transplantation

In specialized circumstances, researchers have successfully transplanted healthy mitochondria into cells with dysfunctional mitochondria, restoring function. While not yet clinically applicable, this concept demonstrates the principle that mitochondrial dysfunction isn't inevitably permanent.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know About Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Aging

Mitochondrial dysfunction is fundamental to aging: Rather than merely a consequence of aging, mitochondrial deterioration drives multiple age-related diseases simultaneously. This understanding has shifted how researchers approach age-related disease treatment.

Multiple, interconnected mechanisms drive mitochondrial aging: The process isn't simple—it involves ROS accumulation, mtDNA mutations, impaired mitochondrial dynamics, calcium dysregulation, and NAD+ depletion. Effective interventions must address multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

Exercise is the gold standard intervention: While pharmaceuticals show promise, regular physical activity remains the single most powerful intervention for restoring mitochondrial function. Combining resistance training and aerobic exercise produces comprehensive benefits.

Pharmacological interventions are rapidly advancing: NAD+ boosters, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants, and compounds enhancing mitochondrial quality control show exciting promise in clinical trials. These interventions often work synergistically with exercise.

Precision medicine is the future: Individual variation in mitochondrial function and therapeutic response suggests customized approaches will outperform one-size-fits-all strategies. Genetic profiling and functional testing should guide therapeutic selection.

Combination approaches are superior: No single intervention optimally addresses all aspects of mitochondrial dysfunction. Combining exercise with targeted pharmaceutical interventions produces superior results.

Prevention is vastly superior to treatment: Maintaining mitochondrial health through regular exercise throughout life prevents the cascade of dysfunction that requires intensive intervention in advanced age.

FAQs: Common Questions About Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Aging

Q: At what age does mitochondrial dysfunction typically begin?

A: Mitochondrial dysfunction begins subtly in middle age (40s-50s) but accelerates significantly after age 60-65. However, even younger individuals can experience mitochondrial decline if sedentary or exposed to chronic stress. The good news: mitochondrial biogenesis can be stimulated at any age through exercise.

Q: Can I reverse mitochondrial dysfunction, or can I only slow it down?

A: Recent research, particularly Bishop et al. (2025), demonstrates that mitochondrial dysfunction can be substantially reversed through regular exercise and lifestyle interventions. While you cannot restore mitochondria to youthful states if severely compromised, comprehensive interventions can restore function to healthy levels in most cases.

Q: Which is better for mitochondrial health: resistance training or aerobic exercise?

A: Research by Zhang and colleagues (2025) indicates both are essential. Resistance training optimally stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and rebuilds muscle, while aerobic exercise enhances mitochondrial oxidative capacity. The ideal approach combines both: 2-3 weekly resistance sessions plus 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity.

Q: Are antioxidant supplements helpful for mitochondrial health?

A: Surprisingly, evidence suggests excessive antioxidant supplementation may actually impair mitochondrial adaptation to exercise. Exercise-induced ROS triggers beneficial adaptive responses; excessive antioxidants blunt these responses. Natural antioxidants in food (polyphenols) are preferable. However, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants like MitoQ show promise because they work differently from standard supplements.

Q: Should I take NAD+ boosters like NMN or NR?

A: This depends on individual circumstances and is best determined through consultation with a healthcare provider. NAD+ boosters show promise in research, particularly combined with exercise. However, they're expensive and not yet standard clinical practice. Some evidence suggests exercise alone produces NAD+ improvements, though supplementation may provide additional benefit, particularly in advanced age or severe mitochondrial dysfunction.

Q: Can I develop mitochondrial disease from lifestyle factors, or is it purely genetic?

A: Both factors matter. While some mitochondrial diseases are genetic, acquired mitochondrial dysfunction develops through lifestyle factors: sedentary behavior, poor diet, chronic stress, sleep deprivation, and exposure to toxins all damage mitochondrial function over time. The encouraging news: most acquired mitochondrial dysfunction responds well to lifestyle intervention (Somasundaram et al., 2024).

Q: How quickly do mitochondrial adaptations occur with exercise?

A: Initial molecular changes occur within days (activation of PGC-1α and NAD+ pathways), but measurable improvements in mitochondrial biogenesis and ATP production typically require 4-8 weeks of consistent exercise. Significant functional improvements often require 3-6 months of dedicated training.

Q: Are there foods that specifically support mitochondrial health?

A: Polyphenol-rich foods (berries, dark chocolate, green tea, red wine) provide compounds that activate sirtuins and promote mitochondrial biogenesis. Complex carbohydrates support mitochondrial oxidative capacity, while adequate protein supports both mitochondrial protein synthesis and muscle maintenance. Mediterranean and Nordic diets emphasize mitochondrial-supportive foods.

Call to Action: Take Control of Your Mitochondrial Health Today

The research is clear: mitochondrial dysfunction drives aging and age-related disease, but you have tremendous power to prevent, slow, and even partially reverse this process. The scientific evidence, synthesized from 2024-2025 cutting-edge research, shows three priorities:

1. Make Exercise Your Medicine

Don't wait for pharmaceutical breakthroughs. Start today with a sustainable exercise program. If you're currently sedentary, begin with walking 20-30 minutes daily. Add resistance training as you build fitness. The evidence from cutting-edge research unequivocally demonstrates that consistent exercise is the single most powerful anti-aging intervention available (Bishop et al., 2025). Your 40-year-old self will thank your 60-year-old self for starting now.

2. Optimize Foundational Lifestyle Factors

Support your mitochondrial function through quality sleep (7-9 hours nightly), stress management, and a whole-food diet rich in polyphenols and antioxidants. These foundational approaches cost nothing and provide comprehensive benefits.

3. Consider Strategic Supplementation or Medical Consultation

If you're experiencing age-related symptoms (persistent fatigue, muscle weakness, cognitive changes), discuss with your healthcare provider whether NAD+ boosters, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants, or other emerging interventions might benefit your individual situation. The research supporting these approaches is rapidly advancing, but they work best alongside, not instead of, exercise and lifestyle optimization.

The Bottom Line: Your mitochondria aren't inevitably destined to decline with age. Armed with understanding of the mechanisms driving mitochondrial dysfunction and the proven interventions that restore function, you can proactively protect your healthspan and independence as you age. Start today—your cellular powerhouses will thank you.

Last Updated: December 2025 | This article synthesizes peer-reviewed research from leading scientific journals and is optimized for readers seeking evidence-based information about mitochondrial dysfunction, aging, and therapeutic interventions.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

.Related Articles

The Science of Healthy Brain Aging: Microglia, Metabolism & Cognitive Fitness | DR T S DIDWAL

The Aging Muscle Paradox: How Senescent Cells Cause Insulin Resistance and The Strategies to Reverse It | DR T S DIDWAL

VO2 Max & Longevity: The Ultimate Guide to Living Longer | DR T S DIDWAL

Blue Zones Secrets: The 4 Pillars of Longevity for a Longer, Healthier Lifepost | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Bishop, D. J., Lee, M. J., & Picard, M. (2025). Exercise as mitochondrial medicine: How does the exercise prescription affect mitochondrial adaptations to training? Annual Review of Physiology, 87(1), 107–129. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-022724-104836

Jia, D., Tian, Z., & Wang, R. (2023). Exercise mitigates age-related metabolic diseases by improving mitochondrial dysfunction. Ageing Research Reviews, 91, 102087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102087

Jia, L., Wei, Z., Luoqian, J., Wang, X., & Huang, C. (2025). Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging: Future therapies and precision medicine approaches. MedComm – Future Medicine, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/mef2.70026

Memme, J. M., Erlich, A. T., Phukan, G., & Hood, D. A. (2021). Exercise and mitochondrial health. The Journal of Physiology, 599(3), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278853

Somasundaram, I., Jain, S. M., Blot-Chabaud, M., Pathak, S., Banerjee, A., Rawat, S., Sharma, N. R., & Duttaroy, A. K. (2024). Mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with age-related disorders. Frontiers in Physiology, 15, 1384966. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1384966

Xu, X., Pang, Y., & Fan, X. (2025). Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: From mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 10, 190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-025-02253-4

Zhang, C., Zheng, X., Xiang, L., et al. (2025). Exercise-mediated regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in aging muscle: Implications for mitochondrial diseases. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-025-05441-6