Isometric vs. Dynamic Resistance Training: What the Science Says About Building Strength

Explore the latest 2025 research comparing isometric and dynamic resistance training. Learn about neuromuscular adaptations, task specificity, and how to combine both for optimal strength gains and injury rehab

EXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

1/30/202612 min read

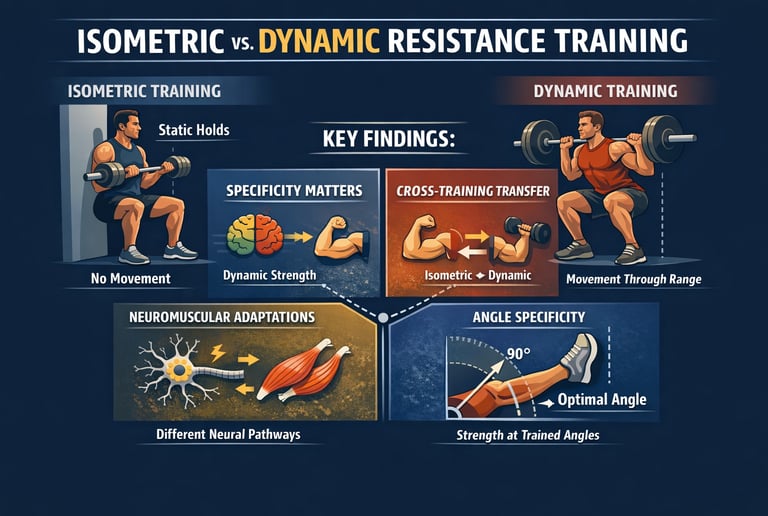

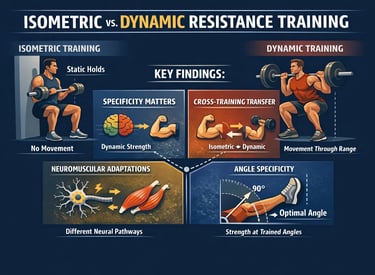

Strength is often treated as a single, unified quality—something you either have or don’t. Yet beneath every display of force lies a more complex reality: strength is task-specific, angle-dependent, and neurologically mediated. Whether a muscle produces force while moving through space or while holding a fixed position fundamentally alters how the nervous system is recruited, how muscle fibers are engaged, and how adaptations are expressed. This distinction sits at the heart of an ongoing scientific debate: is strength best developed through dynamic movement or static force production?

Dynamic resistance training—characterized by concentric and eccentric muscle actions across a range of motion—has long been considered the cornerstone of strength development. However, a growing body of evidence shows that isometric training, once viewed as supplementary or rehabilitative, can induce substantial neuromuscular adaptations when performed with sufficient intensity and intent (Oranchuk et al., 2019). Acute studies demonstrate that even a single session of isometric loading can meaningfully alter neuromuscular function, highlighting that static contractions are far from physiologically inert (Lum & Howatson, 2025).

More importantly, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses reveal that the relationship between isometric and dynamic strength is neither interchangeable nor isolated. Strength gains demonstrate partial but incomplete transfer between modalities, shaped by joint angle, muscle length, velocity, and testing conditions (James et al., 2023; Ghayomzadeh et al., 2025). Dynamic training tends to favor movement-based strength outcomes, while isometric training excels at improving force production at specific joint angles—yet both share overlapping neural mechanisms (Saeterbakken et al., 2025).

Understanding these distinctions is not academic hair-splitting; it has direct implications for performance optimization, injury management, and efficient program design. This chapter examines the science comparing isometric and dynamic resistance training, synthesizing recent evidence to clarify how—and when—each method should be applied to build real-world strength.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Stuck Point" Solution (Overcoming Isometrics)

Utilise Overcoming Isometrics to address specific "sticking points" in a dynamic strength curve. Because strength gains are angle-specific, maximal voluntary contractions against an immovable resistance can increase neural drive at the exact joint angle where a patient or athlete is weakest.

If you find a certain part of a movement—like the very bottom of a squat—is where you always fail, try pushing as hard as you can against a bar that won't move at that exact height. It "teaches" your nervous system how to recruit more muscle exactly where you need it most.

2. The "Safety Valve" for Painful Joints

Isometric training provides a potent analgesic effect and allows for high mechanical tension without the shear stress of joint movement. This makes it an ideal "entry point" for loading tissues during the early phases of tendon or joint rehabilitation.

If moving your arm or leg through a full range hurts, don't stop training. Holding a heavy weight still (Isometrics) lets you keep your muscles strong and can actually help numb the pain without irritating the joint.

3. The Efficiency of "Micro-Loading"

Acute neuromuscular responses to isometrics are comparable to heavy resistance training but with significantly lower metabolic and systemic fatigue. This allows for higher frequency "micro-dosing" of strength stimuli without compromising recovery for other athletic tasks.

Short on time? You don't always need an hour at the gym. A few sets of 10-second maximum-effort holds can give your nervous system a "strength spark" similar to lifting heavy weights, but without leaving you feeling exhausted for the rest of the day.

4. The Transferability Gap

While Dynamic-to-Isometric transfer is robust, Isometric-to-Dynamic transfer is less efficient. Clinicians should view isometrics as a supplement to, rather than a total replacement for, dynamic movement to ensure functional movement patterns and coordination are maintained.

Training "still" will make you better at moving, but training "moving" is even better at making you strong when you're still. To be truly capable in the real world, you need a mix of both, but keep the moving exercises as your main foundation.

5. The Blood Pressure "Brake"

High-intensity isometrics can induce a significant pressor response (rapid spike in blood pressure). Patients with cardiovascular risk factors should utilize "Yielding" isometrics with lower intensities and ensure they maintain continuous breathing (avoiding the Valsalva manoeuvre) to mitigate risk.

When holding a heavy position, your blood pressure can spike quickly. To stay safe, never hold your breath like you’re underwater; keep your air moving in and out. If you have heart or blood pressure concerns, focus on lighter holds for longer periods rather than maximum-effort pushes.

What Are Isometric and Dynamic Resistance Training?

Before diving into the research, let's establish clear definitions.

Dynamic resistance training involves moving a load through a full range of motion against resistance. Think of traditional weightlifting: squats, bench presses, deadlifts, and rowing movements where the muscle lengthens and shortens through multiple joint angles. This is the most common form of strength training found in gyms worldwide.

Isometric strength training, by contrast, involves generating force against immovable resistance without changing the joint angle. Picture holding a heavy weight in a fixed position, performing a plank, or pressing against a wall. The muscle contracts but doesn't move through space—the length remains constant while tension builds.

Overcoming vs. Yielding Isometrics

Overcoming (Intense Functional) Isometrics: You are trying to move an immovable object (e.g., pushing a barbell against the pins of a power rack).

The "Feel": High neural drive and maximal voluntary contraction. It is "proactive" and excellent for breaking through dynamic sticking points.

Yielding Isometrics: You are trying to prevent an object from moving you (e.g., holding a goblet squat at the bottom).

The "Feel": High metabolic stress and eccentric-like strain. It is "reactive" and often more effective for hypertrophy because it’s easier to maintain high mechanical tension for longer durations.

Both methods activate muscle fibers and create adaptation signals, but they do so through fundamentally different mechanical pathways. This distinction becomes crucial when examining neuromuscular function, strength transfer, and training specificity.

Study 1: Lum & Howatson (2025) on Acute Neuromuscular Effects

The first study by Lum and Howatson (2025) directly compared acute neuromuscular responses between a single session of isometric strength training and heavy resistance training. Published in the Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise, this research examined how the nervous system and muscles respond immediately following these distinct training modalities.

The researchers measured neuromuscular function immediately after training, capturing real-time changes in how effectively muscles can generate force. This "acute effects" framework is critical because it reveals the immediate physiological stress and adaptation signals triggered by each training style.

Key Takeaways:

Both isometric training and heavy dynamic training produce measurable acute effects on neuromuscular function

The nature of these acute changes differs between training types, suggesting different neurological pathways are activated

Single sessions of isometric work can meaningfully stress the neuromuscular system without requiring movement through range

The acute stress response—however different—indicates both methods create potent stimuli for adaptation

If you're short on time or working around joint limitations, isometric training delivers genuine neuromuscular stress in a compressed timeframe. The fact that acute responses differ doesn't diminish their effectiveness; it merely indicates that different neural recruitment patterns are being engaged.

Study 2: Ghayomzadeh et al. (2025) - The Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Ghayomzadeh and colleagues (2025) conducted an ambitious systematic review with meta-analysis, examining multiple studies to answer a critical question: How do isometric and dynamic resistance training compare in building both isometric and isokinetic strength?

This meta-analytic approach is particularly powerful because it synthesizes findings across numerous studies, revealing patterns that individual experiments might miss. The researchers evaluated isometric muscular strength (force in fixed positions) and isokinetic muscular strength (force measured across ranges of motion at controlled velocities).

Key Findings:

Isometric training produces robust improvements in isometric strength measurements (force in static holds)

Dynamic resistance training generates superior gains in isokinetic strength (movement-based strength assessments)

However, there is meaningful cross-over effect: isometric training does transfer to dynamic strength, and vice versa, though not with perfect equivalence

The degree of transfer depends on the specificity of training, the angle at which isometric work is performed, and the duration of the training intervention

This finding challenges the notion that training must perfectly match the testing method. If your goal is overall strength development, you can train using isometric methods and still see improvements in dynamic strength, though the gains might be somewhat diminished compared to if you trained dynamically. This principle—known as cross-training transfer—expands the toolkit available to athletes and fitness enthusiasts.

Study 3: Saeterbakken et al. (2025) - Task Specificity and Transferability

Saeterbakken and colleagues (2025) addressed a fundamental principle in exercise science: task specificity. Their systematic review examined whether dynamic resistance training transfers to non-trained isometric strength, and more broadly, how the principle of specificity shapes strength gains.

The principle of specificity suggests that muscles adapt specifically to the demands placed upon them. If you train dynamically, your body becomes particularly good at dynamic tasks. If you train isometrically, you excel at static strength. But the research team investigated how clean this distinction actually is.

Critical Research Findings:

Dynamic training does transfer to isometric strength, but the magnitude of transfer varies considerably

The angle of measurement matters significantly: gains are greatest at or near the training angle

Muscle activation patterns during dynamic training are richer and more varied than those of isometric training, providing broader neural adaptations

However, the specificity principle isn't absolute: training in one modality provides measurable benefits to the other, suggesting overlapping neuromuscular adaptations

The velocity of movement and range of motion engaged during dynamic training influence how well gains transfer to static strength

For athletes or individuals seeking comprehensive strength development, this research validates a mixed-training approach. Rather than choosing one modality exclusively, a strategic combination of dynamic and isometric work exploits the strengths of each while compensating for their limitations. A program emphasizing dynamic compound lifts with supplemental isometric holds at key joint angles may optimize strength development across multiple contexts.

Study 4: James et al. (2023) - Relationship Between Isometric and Dynamic Strength

While the previous studies were published in 2025, James and colleagues' 2023 research remains highly relevant, providing a foundational analysis of the relationship between isometric and dynamic strength following resistance training interventions.

This systematic review with meta-analysis specifically examined the level of agreement between isometric and dynamic strength measures. In other words: if someone becomes very strong in dynamic lifts, how strong are they likely to be in isometric measures, and vice versa?

Key Findings:

Positive correlation exists between isometric and dynamic strength, indicating they share common neuromuscular mechanisms

The correlation is moderate to strong, not perfect, suggesting they're related but distinct qualities

Training adaptations don't transfer with 100% efficiency from one modality to another

Athletes who train primarily in one modality show measurable but diminished capacity in the other

Muscle fiber recruitment, neural drive, and mechanical advantage differ between modalities, explaining the incomplete transfer

The relationship between isometric and dynamic strength is like the relationship between two overlapping circles. There's substantial overlap—shared mechanisms, common muscle groups, integrated neural pathways—but also distinct territories unique to each. This explains why elite powerlifters (who train dynamically) might not dominate at isometric grip strength tests, and vice versa.

Synthesizing the Evidence: What the Research Tells Us

Principle 1: Specificity Rules, But Isn't Absolute

All four studies converge on a fundamental principle: training specificity matters. The mode of training you emphasize will produce the most pronounced adaptations in that same mode. However, this specificity principle operates on a spectrum rather than as an absolute rule.

When you engage in dynamic resistance training, you'll develop superior capacity for dynamic strength tasks, particularly at the velocities and ranges of motion you train. When you emphasize isometric strength training, you'll excel at generating force in static positions, especially at trained angles. But substantial carryover exists between them.

Principle 2: Neuromuscular Adaptations Differ

The research makes clear that isometric and dynamic training trigger different neuromuscular adaptations. Lum & Howatson's work on acute neuromuscular function reveals these differences emerge immediately, suggesting they're not trivial variations but fundamental differences in how the nervous system responds.

Dynamic training engages muscles through varied ranges, recruiting different fiber types at different positions, creating complex neural coordination patterns. Isometric training creates intense force production at specific angles with simplified biomechanics. Each approach has consequences for how the nervous system adapts.

Principle 3: Cross-Training Transfer is Real but Imperfect

Perhaps most practically relevant: the meta-analyses from both Ghayomzadeh and Saeterbakken demonstrate that cross-modality transfer is genuine. You don't need to train exclusively in one modality to develop strength in another. However, this transfer isn't 100% efficient.

If your primary goal is building dynamic strength, the most efficient path is dynamic training. If isometric strength is your target, isometric training is optimal. But if you're pursuing general strength development, combining both modalities is valid and beneficial.

Principle 4: The Angle-Specificity Window

Multiple studies emphasize the importance of angle specificity: isometric strength gains are greatest at the trained angle and diminish as you move away from that angle. This suggests that strategic choice of isometric hold positions—selecting angles that align with your sport-specific or functional goals—enhances the practical value of isometric training.

Practical Applications: Designing Your Training Program

For General Strength Development

Primary focus (60-70% of volume): Dynamic compound movements (squats, deadlifts, presses, rows, pulls) through full ranges of motion

Supplemental work (30-40% of volume): Isometric holds at key positions (bottom of squat, top of deadlift lockout, pressing position), particularly at angles where you feel weaker or more unstable

This combination exploits the neural adaptations and varied muscle recruitment of dynamic work while strategically addressing weak positions through isometric training.

For Athletes with Limited Time

If you have minimal training time available, isometric work delivers substantial neuromuscular stimulus in abbreviated timeframes. A 15-minute session of heavy isometric holds can create meaningful acute effects on neuromuscular function, making it a viable option when full dynamic sessions aren't possible.

For Injury Management or Rehabilitation

Isometric training's primary advantage in rehabilitation contexts is providing neuromuscular stimulus without moving through ranges of motion that might irritate healing tissues. As research confirms meaningful adaptation occurs through isometric stimulus alone, this modality becomes particularly valuable during recovery from injuries.

For Sport-Specific Preparation

Understanding the principle of specificity, athletes should emphasize training modalities that match their sport's demands. A sprinter benefits from dynamic leg training emphasizing explosive power. A grappler benefits from isometric work at positions matching common holds and pressure points. A general strength athlete benefits from both, weighted toward their competition requirements.

FAQs: Answering Your Questions

Q: Will isometric training make me slower or less coordinated?

A: No. While isometric training produces its most pronounced gains in static strength, substantial transfer to dynamic strength occurs (as demonstrated by Ghayomzadeh and colleagues). Additionally, isometric training doesn't interfere with dynamic skill development; it simply doesn't develop it as efficiently as dynamic training does. Combined with dynamic work, isometric training is complementary, not competitive.

Q: Can I build significant muscle size (hypertrophy) using only isometric training?

A: Yes, though perhaps not as efficiently as dynamic training. Isometric contractions do create mechanical tension and muscle damage—two primary drivers of hypertrophy. However, dynamic training's varied joint angles may provide broader stimulation of muscle fibers across different regions. For optimal hypertrophy, combining both modalities is ideal.

Q: How long should I hold an isometric position to see strength gains?

A: Research suggests that hold durations of 6-30 seconds can produce strength adaptations, with longer durations creating greater metabolic stress. For pure strength development, shorter, heavier holds (6-10 seconds) are often sufficient. Increasing duration increases metabolic demands and endurance-strength hybrid qualities.

Q: If I train dynamically, do I need any isometric work?

A: Not necessarily, but it's beneficial. Pure dynamic training will build strength effectively. Isometric supplementation targets weak points, reduces injury risk by building stability at end ranges, and provides variation that supports long-term adaptation. For serious athletes, adding 10-20% of training volume as isometric work is a smart strategy.

Q: Is one method better for older adults or people with joint problems?

A: Isometric training can be advantageous in these populations because it avoids end-range positions and doesn't require dynamic control through space. However, many older adults and people with mild joint concerns can tolerate well-designed dynamic training. The ideal approach is usually a carefully scaled combination of both, with exercise selection and load management tailored to individual capacity.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Remember

Both isometric and dynamic resistance training produce genuine strength adaptations, but through different neuromuscular mechanisms.

The principle of specificity is real: training will produce its greatest gains in the specific modality emphasized. However, substantial cross-modality transfer occurs.

Neuromuscular function changes differently between modalities, suggesting distinct neural adaptations that complement one another.

For comprehensive strength development, a mixed approach combining dynamic work (primary) with isometric supplementation (secondary) optimizes results across multiple strength contexts.

Isometric training excels in time-efficient scenarios, injury management, and addressing weak points; dynamic training excels in building multi-angle strength and sport-specific power.

The transfer from dynamic to isometric strength is more robust than from isometric to dynamic, suggesting dynamic training is the foundation with isometric work as valuable supplementation.

Angle specificity matters: isometric gains are greatest at trained angles, making position selection strategically important.

Author’s Note

This chapter was written to bridge the gap between exercise science research and real-world strength training practice. Rather than treating isometric and dynamic resistance training as competing methods, the goal is to clarify how each modality contributes to strength development through distinct—yet overlapping—neuromuscular mechanisms. The evidence synthesized here draws primarily from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, ensuring that conclusions reflect the highest level of available scientific rigor.

Where possible, emphasis has been placed on principles that consistently emerge across studies—specificity, angle dependence, neural adaptation, and partial transfer of strength—rather than on isolated findings. Practical recommendations are intentionally framed as flexible guidelines, not rigid prescriptions, recognizing that individual goals, injury history, training experience, and sport demands ultimately determine optimal program design.

This chapter is intended for clinicians, strength and conditioning professionals, students of exercise science, and scientifically curious trainees who seek an evidence-based understanding of how strength is built, expressed, and transferred. Any remaining limitations reflect those of the existing literature, and readers are encouraged to view strength training as an evolving discipline where intelligent integration, not methodological exclusivity, produces the most robust outcomes

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new exercise regimen, especially if you have existing health conditions or take medications.

Related Articles

Muscular Endurance Training: Evidence-Based Strategies for Strength and Performanc | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Build a Disease-Proof Body: Master Calories, Exercise & Longevity | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Maximize Muscle Growth: Evidence-Based Strength Training Strategies | DR T S DIDWAL

Lower Blood Pressure Naturally: Evidence-Based Exercise Guide for Metabolic Syndrome | DR T S DIDWAL

Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia: The Critical Connection | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Ghayomzadeh, M., Li, J., Eidy, F., Keshavarz, M., Sabag, A., Fornusek, C., & Hackett, D. A. (2025). Effects of isometric vs. dynamic resistance training on isometric and isokinetic muscular strength: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 28(12), 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2025.07.011

James, L. P., Weakley, J., Comfort, P., & Huynh, M. (2023). The relationship between isometric and dynamic strength following resistance training: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and level of agreement. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 19(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2023-0066

Lum, D., & Howatson, G. (2025). Comparing the acute effects of a session of isometric strength training with heavy resistance training on neuromuscular function. Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise, 7, 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-023-00241-0

Saeterbakken, A. H., Stien, N., Paulsen, G., et al. (2025). Task specificity of dynamic resistance training and its transferability to non-trained isometric muscle strength: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 55, 1651–1676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02225-2