How Exercise Lowers LDL and Raises HDL: A Science-Backed Plan for Heart Health

Lower LDL and raise HDL in 12 weeks? Discover the 2025 science behind aerobic exercise, strength training, and HIIT for heart health

EXERCISEMETABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/19/20269 min read

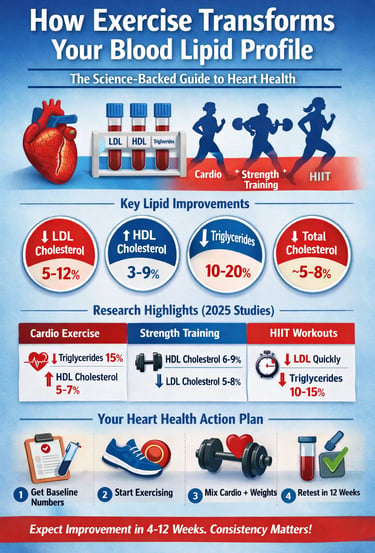

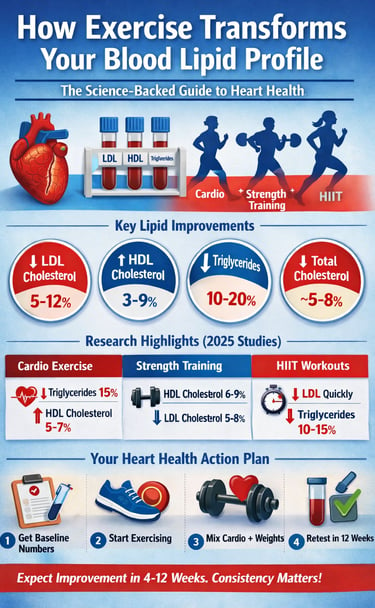

For decades, cholesterol management has been framed almost exclusively around diet and medication. Patients are told to cut saturated fat, take a statin, and monitor stubbornly resistant numbers. Yet a growing body of high-quality evidence now makes one point unmistakably clear: exercise is not merely supportive therapy—it is a direct modifier of blood lipid metabolism. In many cases, its effects rival those of pharmacologic interventions. Large systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in the last few years demonstrate that structured exercise training consistently lowers low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, raises high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and reduces triglycerides across diverse populations (Smart et al., 2025; Buzdagli et al., 2022). Importantly, these changes are not cosmetic. Even modest LDL reductions of 5–10% are associated with meaningful reductions in atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk, while small HDL increases are associated with improved reverse cholesterol transport and plaque stability. What is often overlooked is that different types of exercise act through different biological pathways. Aerobic training enhances lipoprotein lipase activity and triglyceride clearance; resistance training improves HDL synthesis and insulin sensitivity; and high-intensity interval training (HIIT) accelerates hepatic lipid turnover and metabolic flexibility (De Oude et al., 2025; Ko et al., 2025). The result is a complementary, additive effect when these modalities are combined. Crucially, recent evidence suggests that individuals with overweight, obesity, or metabolic dysfunction may experience even greater lipid improvements than lean counterparts, challenging the notion that “it’s too late to benefit” (Chen et al., 2025). Within as little as 8–12 weeks, laboratory-measurable improvements in LDL, HDL, and triglycerides are commonly observed. This emerging science reframes exercise as a precision tool for lipid optimization, not a generic lifestyle recommendation—and it demands a more deliberate, evidence-based approach to training for heart health. For expert readers, the transformation of the lipid profile is driven by a sophisticated "triad" of molecular adaptations that optimize how the body transports and clears fats.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Clean-Up Crew" Effect (HDL & LPL)

Scientific Tone: Exercise increases the activity of Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL) in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, which accelerates the breakdown of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.

Think of exercise as "hiring more workers" for your blood's cleaning crew. It boosts enzymes that sweep fat out of your bloodstream and into your muscles to be burned as fuel, preventing it from sticking to your artery walls.

2. Intensity is the "HDL Dial"

Scientific Tone: Meta-analyses indicate a dose-response relationship between resistance training intensity and High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) increases; higher loads (70-85% 1RM) elicit more significant proteomic changes.

Patient-Professional: If you want to raise your "good" cholesterol, lifting heavier weights is better than lifting light ones. While any movement helps, pushing your strength limits acts like a volume knob for your HDL levels.

3. The Synergy of "Concurrent Training"

Scientific Tone: Combined aerobic and resistance protocols (Concurrent Training) produce additive effects, targeting both Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) reduction and metabolic flexibility simultaneously.

Don't just pick one! Combining a brisk walk (cardio) with some weightlifting (strength) is the "gold standard." It’s like using both soap and a scrub brush to clean a surface—each works differently, but they are most effective when used together.

4. The 12-Week "Cellular Lag"

Scientific Tone: While acute metabolic shifts occur post-exercise, significant changes in the lipid profile (especially LDL and Total Cholesterol) typically require a minimum of 8 to 12 weeks of consistent stimulus to manifest in serum samples.

Your blood chemistry is like a large ship; it takes time to turn around. Don’t be discouraged if your labs don't look perfect after two weeks of jogging. Your body needs about three months of consistency to "reprogram" its fat-processing system.

5. Body Composition vs. Lipid Health

Scientific Tone: In overweight and obese populations, exercise-induced lipid improvements can occur independently of significant weight loss, suggesting intrinsic metabolic adaptations within the liver and muscle tissue.

The scale can be a liar. Even if your weight isn't dropping as fast as you’d like, your blood is getting healthier. Exercise "tunes" your internal organs to handle fat better, even before you see a change in your clothing size.

6. Triglycerides: The "Quickest Win"

Scientific Tone: Post-prandial (after-meal) triglyceride levels are acutely sensitive to aerobic activity, which enhances the clearance of chylomicrons and VLDL from the plasma.

Triglycerides are the most "reactive" of your blood fats. A single 30-minute walk after a meal can immediately help your body clear out the fats you just ate, making it one of the fastest ways to protect your heart on a daily basis.

What Are Blood Lipids? A Quick Primer

Blood lipids are fatty substances in your bloodstream. Your lipid panel measures:

• Total Cholesterol: The sum of all cholesterol in your blood

• LDL Cholesterol: Often called 'bad cholesterol' because it deposits in artery walls

• HDL Cholesterol: Often called 'good cholesterol' because it removes excess cholesterol from arteries

• Triglycerides: Another fat that can contribute to artery hardening when elevated

The Molecular Mechanism of Lipid Remodeling

LPL Up-regulation: Physical activity stimulates the skeletal muscles to increase the production of Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL). This enzyme sits on the capillary walls; as blood flows by, LPL "unpacks" triglycerides from circulating chylomicrons and VLDL, converting them into free fatty acids for energy use. This is why aerobic exercise is particularly potent at clearing post-meal fat from the blood.

Hepatic LDL Receptor Sensitivity: Exercise appears to enhance the expression and recycling of LDL receptors in the liver. By increasing the number of active receptors, the liver can more efficiently "capture" and remove LDL particles from the bloodstream, effectively lowering the circulating "bad" cholesterol.

Insulin-Lipid Crosstalk: Exercise-induced improvements in insulin sensitivity (primarily via increased GLUT4 translocation) have a secondary effect on the liver. When insulin works efficiently, it inhibits the overproduction of Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein (VLDL), which is the precursor to LDL. Consequently, better blood sugar management directly leads to a less "atherogenic" (plaque-forming) lipid profile.

The Meta-Analysis Evidence: What 2025 Research Reveals

Smart et al. (2025): The Gold Standard for Exercise and Lipids

One of the most authoritative recent studies comes from Smart and colleagues, published in Sports Medicine in 2025. This systematic review and meta-analysis examined evidence from numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the definitive effects of exercise training on blood lipids.

Key Findings:

• LDL cholesterol decreased by approximately 5-10% in pooled analyses

• HDL cholesterol increased by 3-7% with consistent training

• Triglycerides reduced by 5-15% depending on exercise type

• Total cholesterol declined by roughly 5% on average

Chen et al. (2025): Exercise in Overweight and Obese Populations

A particularly relevant recent study from Chen and colleagues, published in Life (2025), examined aerobic exercise effects on blood lipids in people with overweight or obesity.

Key Findings:

• LDL cholesterol reductions of 7-12% in overweight/obese groups

• HDL cholesterol increases of 5-9%

• Triglyceride reductions of 10-20% (more dramatic than normal-weight populations)

• Total cholesterol decreases averaging 6-8%

Resistance Exercise: Reshaping Your Lipid Profile with Strength

De Oude et al. (2025): Resistance Training Intensity Matters

A groundbreaking 2025 systematic review by Kirsten de Oude and colleagues in the European Heart Journal Open examined whether resistance exercise intensity affects lipid improvements.

Key Findings:

• Higher-intensity resistance training produced superior HDL cholesterol improvements

• LDL cholesterol reductions of 5-8% with consistent resistance training

• Triglyceride reductions of 3-6% (less dramatic than aerobic)

• Combined aerobic-resistance protocols produced additive effects

High-Intensity Interval Training: The Time-Efficient Lipid Transformer

Ko et al. (2025): HIIT's Cardiovascular Benefits

A 2025 narrative review by Ko, So, and Park synthesized evidence on HIIT effects on cardiovascular health and disease prevention.

Key Findings:

• HIIT produces rapid LDL cholesterol reductions in 4-6 weeks

• HDL cholesterol improvements rival aerobic training with shorter duration

• Triglyceride reductions of 10-15% commonly observed

• Metabolic improvements occur more rapidly than steady-state aerobic

Key Takeaways: Your Action Plan

1. Exercise is not “adjunct therapy”—it is metabolic pharmacology.

For decades, lipid management has centered on dietary restriction and statin titration. Yet contemporary meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that structured exercise produces reproducible reductions in LDL-C (≈5–10%), triglycerides (≈5–20%), and modest but meaningful rises in HDL-C. These are not cosmetic shifts; they translate into measurable reductions in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk. Framing exercise as optional lifestyle advice underestimates its biologic potency.

2. Distinct modalities, distinct molecular signatures.

Aerobic training amplifies skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity, accelerating chylomicron and VLDL clearance. Resistance training appears to modulate HDL metabolism and improve insulin sensitivity, indirectly attenuating hepatic VLDL overproduction. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) enhances metabolic flexibility and may accelerate hepatic lipid turnover. The implication is clear: exercise prescription should be deliberate, not generic.

3. The additive power of concurrent training.

When aerobic and resistance modalities are combined, lipid improvements are complementary rather than redundant. LDL reduction, triglyceride clearance, and HDL enhancement are targeted through parallel pathways. In cardiometabolic medicine, this is analogous to combination pharmacotherapy—multiple mechanisms converging on a single outcome: lower residual vascular risk.

4. Weight loss is not the sole mediator.

Compelling data indicate that lipid improvements occur independent of major changes in body weight. Hepatic LDL receptor sensitivity, improved insulin signaling, and intramyocellular lipid oxidation are intrinsic adaptations. Clinicians must therefore shift the narrative away from the scale and toward metabolic remodeling.

5. Time course matters—biology is not instantaneous.

Acute triglyceride reductions can occur within hours of aerobic activity, yet durable LDL and total cholesterol changes generally require 8–12 weeks of consistent stimulus. This temporal distinction is essential for setting realistic expectations and preventing premature therapeutic nihilism.

6. Precision over platitude.

Exercise prescription should include intensity, frequency, progression, and modality—much like a drug regimen. A recommendation of “be more active” is clinically insufficient. Dosing matters.

7. The emerging frontier: beyond LDL-C.

Future discussions must incorporate ApoB, non-HDL cholesterol, particle size, and post-prandial lipemia. Exercise likely exerts effects beyond conventional lipid panels, influencing lipoprotein quality as well as quantity.

8. The clinical mandate.

In an era of escalating cardiometabolic disease, exercise should be positioned as foundational therapy. Not as an alternative to medication, but as a biologically synergistic intervention capable of reducing pharmacologic burden, improving vascular function, and restoring metabolic resilience.

Exercise is not merely movement. It is molecular reprogramming of lipid transport—arguably the most under-prescribed therapy in preventive cardiology.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How quickly will I see changes in my blood lipids?

A: Initial changes often appear within 4-6 weeks of consistent exercise. The most meaningful improvements typically require 8-12 weeks. Retest your lipid panel after 12 weeks to confirm improvements.

Q: Is one type of exercise better than others?

A: No single type dominates. Aerobic exercise best targets triglycerides, resistance training best raises HDL, and HIIT achieves rapid improvements with time efficiency. For comprehensive benefits, combine modalities.

Q: Can exercise replace my cholesterol medication?

A: Don't abandon medications without medical guidance. Exercise produces improvements comparable to some medications. Many individuals can reduce medication doses under physician supervision. Always work with your doctor.

Q: I have severe obesity—will exercise still help?

A: Absolutely, and possibly more dramatically. The Chen et al. (2025) study showed overweight/obese individuals experienced 12% LDL reductions and 20% triglyceride reductions—greater improvements than normal-weight individuals.

Author’s Note

This article was written to bridge the gap between exercise science and everyday cardiovascular care. While cholesterol numbers are often discussed in isolation, blood lipids are dynamic biomarkers that respond powerfully to lifestyle—especially structured physical activity. The evidence summarized here is drawn primarily from recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses (2022–2025), representing the highest level of clinical research available.

My goal was not to promote a single “best” exercise method, but to show how different forms of exercise exert complementary effects on LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and overall atherosclerotic risk. When properly prescribed and consistently performed, exercise functions as a true metabolic therapy—often enhancing, and sometimes reducing the need for, pharmacological interventions under medical supervision.

This article is intended for clinicians, health professionals, and scientifically curious readers who value evidence over trends. It should not replace individualized medical advice. Patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or those taking lipid-lowering medications should always consult their physician before modifying treatment plans.

Medical Disclaimer

The information in this article, including the research findings, is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Related Articles

Metabolic Plasticity: Epigenetic Adaptations to Calorie Restriction | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Buzdagli, Y., Tekin, A., Eyipinar, C. D., Öget, F., & Siktar, E. (2022). The effect of different types of exercise on blood lipid profiles: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Science & Sports, 37(8), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2022.07.005

Chen, Z., Zhou, R., Liu, X., Wang, J., Wang, L., Lv, Y., & Yu, L. (2025). Effects of aerobic exercise on blood lipids in people with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Life (Basel, Switzerland), 15(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15020166

De Oude, K. I., Elbers, R. G., Gerger, H., Maes-Festen, D. A. M., & Oppewal, A. (2025). The effect of different resistance exercise training intensities on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Heart Journal Open, 5(5), oeaf093. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjopen/oeaf093

Ko, J.-M., So, W.-Y., & Park, S.-E. (2025). Narrative review of high-intensity interval training: Positive impacts on cardiovascular health and disease prevention. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 12(4), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12040158

Ouda, L. K. (2025). The impact of exercise on blood lipoprotein cholesterol profiles (LDL-HDL): Protecting against atherosclerosis. Journal of Applied Hematology, 16(3), 239–246. https://doi.org/10.4103/joah.joah_77_25

Smart, N. A., Downes, D., van der Touw, T., Hada, S., Dieberg, G., Pearson, M. J., Wolden, M., King, N., & Goodman, S. P. J. (2025). The effect of exercise training on blood lipids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 55(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02115-z