Endothelial Dysfunction: The Central Role of Nitric Oxide in Cardiovascular and Cardiometabolic Disease

Think heart disease starts with a clog? Think again. Discover how endothelial dysfunction and the loss of nitric oxide trigger the silent decline of vascular health

HEART

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/17/202615 min read

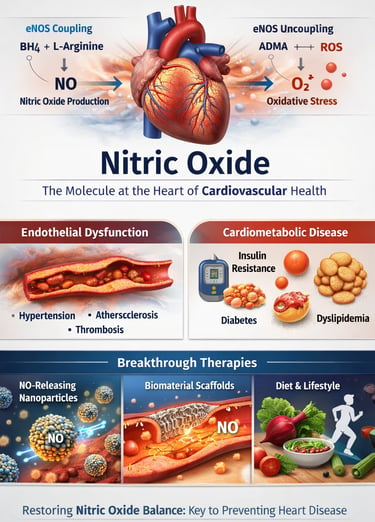

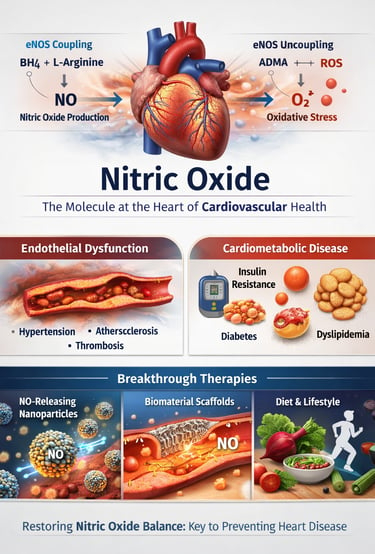

Cardiovascular disease does not begin with a blocked artery—it begins with a failing signal. Long before plaque rupture, thrombosis, or heart failure develop, a subtle biochemical imbalance emerges within the vascular endothelium: diminished nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability. This single molecular disruption links hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and heart failure through a shared pathway of endothelial dysfunction. As outlined in Pharmacological Reviews (Carlström et al., 2024), nitric oxide signaling regulates vascular tone, platelet aggregation, mitochondrial respiration, and inflammatory cascades—making it one of the most critical modulators of cardiovascular homeostasis.

Yet nitric oxide biology is more complex than simple deficiency. Emerging evidence from the International Journal of Molecular Sciences (Venkatesan et al., 2026) demonstrates that oxidative stress, tetrahydrobiopterin depletion, and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) accumulation can “uncouple” endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), transforming a protective enzyme into a source of superoxide. This biochemical shift not only reduces NO production but accelerates vascular injury.

Simultaneously, translational advances described in Nitric Oxide (Nunes et al., 2025) and Biomaterials Research (Sun et al., 2025) are redefining therapeutic possibilities through targeted NO-delivery nanomaterials and regenerative biomaterial scaffolds.

The implication is profound: cardiovascular disease may be less a structural disorder and more a signaling failure. Restoring nitric oxide balance—biochemically, pharmacologically, and metabolically—could represent one of the most powerful preventive strategies in modern cardiometabolic medicine.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Kitchen Pharmacy" Strategy

Scientific Insight: Dietary inorganic nitrate is reduced to nitrite by oral bacteria and subsequently to nitric oxide (NO) in the acidic environment of the stomach and through systemic reductases. This "enterosalivary pathway" provides a critical alternative to the traditional L-arginine-NO synthase (eNOS) pathway, which often fails in diseased states.

You can "feed" your blood vessels. Vegetables like beets, arugula, and spinach are loaded with natural nitrates. When you eat them, your body converts them into nitric oxide, helping your arteries relax and lowering your blood pressure almost like a natural, mild medication.

2. Don't "Rinse Away" Your Heart Health

Scientific Insight: The commensal anaerobic bacteria on the posterior tongue are essential for the bioactivation of dietary nitrate. The use of strong antibacterial mouthwashes can eradicate these colonies, effectively "breaking" the pathway and potentially leading to increased systemic blood pressure.

Your mouth is the gateway to your heart. Using antiseptic mouthwash too often can kill the "good" bacteria that help produce nitric oxide. If you kill those bacteria, you might actually see your blood pressure creep up because your body can't process heart-healthy nitrates from your food.

3. Exercise as a "Mechanical" Drug

Scientific Insight: Physical activity increases laminar shear stress—the frictional force of blood flowing over the vessel wall. This mechanical stimulus activates the enzyme endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), boosting the production of NO and maintaining the "non-stick" surface of the arteries.

Think of exercise as a workout for the inside of your pipes, not just your muscles. As your heart pumps faster during a walk, the blood rubbing against the vessel walls acts as a signal to release nitric oxide. This keeps your vessels flexible and prevents "plaque" from sticking to the walls.

4. The "Rusty Pipe" Problem (Oxidative Stress)

Scientific Insight: In a state of high oxidative stress, nitric oxide quickly reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite. This not only depletes the "good" NO but creates a highly reactive "bad" molecule that further damages proteins and DNA within the vessel wall.

Nitric oxide is fragile. If your body has too much "inflammation" (like a rusty pipe), the nitric oxide gets destroyed before it can do its job. This is why managing stress and eating antioxidants (like colorful berries) is so important—it protects the nitric oxide so it can actually help your heart.

5. Nasal Breathing is a Cardiovascular Act

Scientific Insight: Nitric oxide is continuously produced in the paranasal sinuses. During nasal inhalation, this NO is transported to the lungs, where it improves ventilation-perfusion matching and acts as a potent vasodilator, lowering pulmonary vascular resistance.

Breathe through your nose, not your mouth. Your sinuses actually produce nitric oxide gas. When you inhale through your nose, you carry that gas directly into your lungs, which helps your blood pick up oxygen more efficiently and keeps your pulmonary circulation relaxed.

The Molecule That Decides Vascular Fate

Understanding Nitric Oxide: The Heart's Most Important Messenger

Nitric oxide is a gas molecule produced naturally in your body, primarily within the endothelium—the thin layer of cells lining your blood vessels. When functioning properly, NO performs critical tasks:

Vasodilation: Relaxes blood vessel walls, reducing blood pressure and improving blood flow

Anti-inflammation: Reduces inflammatory markers that damage blood vessels

Anti-thrombosis: Prevents blood clots from forming

Endothelial protection: Maintains the structural integrity of blood vessel linings

However, when nitric oxide production declines or becomes dysregulated—a condition called endothelial dysfunction—cardiovascular disease develops. This is why recent research into nitric oxide dysregulation and restoration strategies is generating such excitement in the medical community.

Study 1: Comprehensive Mechanisms and Therapeutic Frontiers

Key Takeaways:

Nitric oxide dysfunction is central to multiple cardiovascular pathologies, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure

Understanding NO signaling dysregulation at the molecular level is essential for developing targeted interventions

The paper identifies multiple therapeutic frontiers where NO-based interventions could transform cardiovascular disease treatment

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) function and regulation emerge as critical control points

This foundational study provides the mechanistic framework that other researchers build upon when developing new cardiovascular therapies.

Study 2: Revolutionary Nanomaterial-Based NO Delivery Systems

If conventional pharmacology treats the body like filling a glass of water, nanomaterial-based drug delivery is like precisely placing water exactly where it's needed. Nunes et al. (2025) explored this revolutionary approach in their paper on nitric oxide-releasing nanomaterials published in Nitric Oxide.

Key Takeaways:

Nitric oxide-releasing nanomaterials offer superior targeting compared to conventional medications, delivering NO directly to damaged tissue

These innovative nanomaterials can sustain NO release over extended periods, improving therapeutic efficacy

Nanoparticle formulations reduce systemic side effects by concentrating therapeutic agents at disease sites

The field faces challenges in scaling production, ensuring stability, and optimizing biodegradability—but progress is accelerating

Nanomaterial-based therapies represent a bridge between basic science and clinical practice

This research is particularly exciting because it addresses one of medicine's greatest challenges: drug delivery specificity. Instead of flooding the entire body with medication, NO-releasing nanoparticles can target precisely where cardiovascular damage occurs.

Study 3: Biomaterial Therapies for Coronary Heart Disease

Coronary artery disease remains the leading cause of death worldwide, claiming approximately 17.9 million lives annually. Sun et al. (2025 )took a focused approach in Biomaterials Research, examining how nitric oxide integrated into biomaterial scaffolds could revolutionize coronary heart disease treatment.

Key Takeaways:

Biomaterial-based therapies incorporating nitric oxide can promote endothelial regeneration and restore vascular function

NO-releasing scaffolds reduce restenosis (re-narrowing of treated arteries), a major limitation of conventional interventions

These biomaterial systems provide dual benefits: mechanical support and active therapeutic delivery

Translational pathways are advancing rapidly, with several systems moving toward clinical trials

Coronary heart disease treatment paradigms may shift from passive stent placement to active regenerative therapy

What makes this research particularly compelling is its focus on regeneration rather than merely preventing further damage. By combining biomaterial engineering with nitric oxide signaling, researchers are creating therapeutic systems that actually restore normal vessel function.

Study 4: Recent Advances in NO Signaling and Regulation

Sometimes the most important research comes from comprehensive reviews that synthesize decades of work. Carlström et al. (2024), provided an authoritative summary of recent advances in nitric oxide signaling and regulation.

Key Takeaways:

Nitric oxide signaling operates through multiple interconnected pathways, each with distinct physiological roles

Regulation of NO production involves complex interactions between enzymatic, genetic, and environmental factors

Endothelial dysfunction characterized by reduced NO bioavailability, is reversible through targeted interventions

Pharmacological tools for manipulating NO signaling have advanced significantly, enabling more precise therapeutic strategies

Understanding NO regulation mechanisms is essential for developing next-generation cardiovascular medicines

This comprehensive review serves as an essential reference, clarifying the sometimes-confusing landscape of nitric oxide physiology and guiding researchers toward the most promising therapeutic targets.

Study 5: Regulating NO Generation and Consumption

Abu-Soud et al. (2025) tackled a fundamental challenge in NO biology: how the body generates and subsequently consumes nitric oxide. Published in the International Journal of Biological Sciences, this work illuminates the dynamic balance maintaining cardiovascular health.

Key Takeaways:

Nitric oxide generation requires tight regulation to prevent excessive production that could paradoxically damage tissues

NO consumption through reactions with reactive oxygen species is a critical control mechanism

Oxidative stress (excess ROS) disrupts this delicate balance, reducing NO bioavailability

Therapeutic approaches should target both increasing NO production and reducing its consumption through oxidative pathways

The generation-consumption balance is a key therapeutic control point often overlooked in simpler treatment approaches

This research explains why simply "increasing" nitric oxide isn't always the answer—the body's natural NO regulation systems exist for good reasons. Effective cardiovascular therapies must respect this balance.

Study 6: Mechanisms and Strategies for Promoting NO Production

While some research focuses on measuring NO, Gonzalez et al. (2025) took a more practical approach: how can we actually promote nitric oxide production in diseased tissues? Published in Frontiers in Physiology, this work translates mechanistic understanding into actionable strategies.

Key Takeaways:

Dietary approaches (nitrate-rich foods, specific amino acids) can meaningfully increase plasma nitric oxide levels

Exercise and shear stress on blood vessels naturally stimulate endothelial NO synthesis

Pharmaceutical interventions (statins, ACE inhibitors) enhance NO availability as secondary beneficial effects

Combined strategies targeting multiple mechanisms often produce superior results compared to single interventions

Personalized approaches considering individual biochemistry may optimize NO production promotion

This practical focus bridges the gap between laboratory discoveries and lifestyle recommendations patients can actually implement.

Study 7: Redox Signaling in Heart and Brain

Finally, Naderian et al. (2026) broadened the perspective in Metabolic Brain Diseases, examining how nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species interact in redox signaling—the chemical language controlling cellular responses.

Key Takeaways:

Redox signaling balance between NO and ROS is critical for both cardiovascular and neurological health

Oxidative stress (excessive ROS) and reduced NO bioavailability often occur together, creating a vicious cycle

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases share redox signaling abnormalities as common mechanisms

Antioxidant therapies work partially by preserving NO bioavailability through ROS reduction

Integrated therapeutic approaches addressing both NO restoration and oxidative stress reduction show promise

This research reveals connections between cardiovascular disease and neurological complications, suggesting unified therapeutic approaches.

Key Therapeutic Strategies Emerging from Current Research

Based on these seven studies, several compelling therapeutic strategies are emerging:

1. Nanomaterial-Based NO Delivery

Nitric oxide-releasing nanoparticles offer superior targeting and sustained delivery, potentially revolutionizing treatment for acute coronary syndromes and restenosis prevention.

2. Biomaterial Scaffolding

NO-releasing biomaterials provide both structural support and active therapy, addressing multiple aspects of vascular damage simultaneously.

3. Lifestyle and Dietary Interventions

Practical approaches—nitrate-rich foods, regular exercise, stress reduction—enhance endogenous NO production and restore endothelial function.

4. Pharmaceutical Optimization

Leveraging drugs' NO-enhancing properties (statins, ACE inhibitors) while minimizing side effects through combination therapies.

5. Redox Balancing

Addressing both NO bioavailability and oxidative stress simultaneously creates superior outcomes compared to single-target approaches.

Critical Limitations of NO-Based Therapies

Despite promise, NO therapies have limitations:

Short Half-Life: NO is extremely labile; free NO persists only seconds, requiring delivery strategies to be precise.

Off-Target Effects: Excessive vasodilation may cause hypotension, headaches, flushing, especially with systemic NO donors.

Reactive Interactions: In settings of high oxidative stress, added NO can react with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, potentially worsening oxidative damage.

Clinical Translation Lag: Most nanomaterial and biomaterial NO systems are pre-clinical; FDA approval timelines remain long (5–10+ years).

Patient Heterogeneity: Genetic differences (e.g., eNOS polymorphisms) and comorbid conditions (diabetes) alter responsiveness.

NO role in Cardiometabolic Disease

Insulin Resistance: NO modulates capillary recruitment and glucose uptake; reduced NO bioavailability is associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance.

Adipose NO Signaling: NO influences adipose tissue blood flow and lipolysis, contributing to metabolic homeostasis.

Diabetes & Endothelial Dysfunction: Chronic hyperglycemia accelerates eNOS uncoupling, increases ADMA, and amplifies oxidative stress — a central pathway in diabetic vascular disease.

Dyslipidemia Interaction: LDL oxidation reduces NO availability and promotes atherosclerosis; statins improve NO by upregulating eNOS.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is Nitric Oxide the Same as Laughing Gas?

No. Nitric oxide (NO) is a simple two-atom molecule produced naturally in your body. Nitrous oxide (N₂O), called "laughing gas," is an entirely different compound used as an anesthetic. The similarity in names causes confusion, but they're chemically distinct and have completely different effects.

Q2: Can I Take Supplements to Increase Nitric Oxide?

Yes, several approaches work:

L-arginine and L-citrulline amino acids support NO synthesis

Nitrate-rich vegetables (beets, spinach, arugula) provide dietary sources

Antioxidants preserve NO by reducing reactive oxygen species

Always consult healthcare providers before supplementing, especially if taking cardiovascular medications

Q3: How Long Does It Take to Restore Endothelial Function?

Endothelial function improvement typically requires:

Lifestyle changes: 2-4 weeks for noticeable improvements

Pharmaceutical interventions: 4-8 weeks for significant restoration

Combined approaches: Often achieve optimal results within 8-12 weeks

Individual variation is substantial; genetic factors, disease severity, and adherence all matter.

Q4: Are NO-Releasing Nanomaterials Available Now?

Most NO-releasing nanomaterials remain in research or early clinical trials. Several systems show promise, but FDA approval timelines typically span 5-10 years. Some biomaterial products incorporating NO-enhancing properties are emerging in specialized cardiovascular clinics.

Q5: Can Nitric Oxide Dysfunction Be Completely Reversed?

In many cases, yes—especially with early intervention. Endothelial dysfunction from lifestyle factors (smoking, poor diet, sedentary behavior) often reverses completely with comprehensive lifestyle change. Disease-related dysfunction may improve substantially but sometimes requires ongoing management.

Q6: How Do These Treatments Work in Heart Failure?

Nitric oxide restoration helps heart failure through multiple mechanisms:

Improves vascular dilation, reducing cardiac workload

Reduces inflammation that damages heart muscle

Enhances contractility in some cases

Improves oxygen delivery to cardiac tissue

This multi-pathway benefit explains why NO-based approaches show promise across different cardiovascular conditions.

Q7: What About Side Effects of NO-Based Therapies?

Nitric oxide therapies are generally well-tolerated because NO is endogenous (naturally produced). Potential concerns include:

Excessive vasodilation (headaches, dizziness)—rare with modern formulations

Interactions with certain medications (particularly phosphodiesterase inhibitors)

Individual variability in response

Safety profiles continue improving as delivery systems become more sophisticated.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know

Cardiovascular disease does not begin with a blocked artery—it begins with a failing signal.

Long before plaque ruptures or luminal narrowing appear on angiography, endothelial cells lose the ability to generate and regulate nitric oxide (NO), the master signaling molecule of vascular health. This loss is subtle, biochemical, and reversible—yet it is the molecular pivot upon which hypertension, atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and vascular aging turn.

In the modern cardiometabolic landscape, nitric oxide is not merely a vasodilator. It is a redox-sensitive, metabolically integrated signaling hub that governs vascular tone, mitochondrial efficiency, platelet reactivity, inflammation, and endothelial repair. Understanding its biology reframes prevention—not as lipid management alone—but as preservation of endothelial signaling integrity.

Nitric oxide is synthesized from L-arginine by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), a calcium- and shear stress–dependent enzyme requiring tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) as a critical cofactor. In healthy vasculature, eNOS-derived NO diffuses to smooth muscle cells, activates soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), increases cyclic GMP (cGMP), and promotes vasodilation.

But NO does more than relax vessels. It:

Suppresses platelet aggregation

Inhibits leukocyte adhesion

Reduces smooth muscle proliferation

Preserves mitochondrial respiration efficiency

Maintains arterial compliance

This integrated signaling network explains why endothelial dysfunction precedes structural disease. When NO bioavailability falls, inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular remodeling accelerate.

The decline in nitric oxide signaling is rarely due to the absence of eNOS. Instead, it reflects eNOS uncoupling—a state in which the enzyme produces superoxide (O₂⁻) instead of nitric oxide. This occurs when BH4 becomes oxidized or when asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous NOS inhibitor, accumulates.

The consequences are self-amplifying:

Superoxide reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻)

Peroxynitrite oxidises BH4

Further eNOS uncoupling ensues

This redox spiral reduces NO bioavailability while amplifying oxidative injury—a mechanistic bridge linking metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease.

Insulin resistance further compounds this dysfunction. Impaired PI3K-Akt signaling reduces eNOS phosphorylation, while hyperglycemia increases reactive oxygen species via mitochondrial overload and NADPH oxidase activation. Thus, metabolic disease and endothelial failure are biologically inseparable.

Beyond enzymatic synthesis lies a second, evolutionarily conserved pathway: the dietary nitrate–nitrite–NO axis.

Dietary nitrates (abundant in leafy greens and beetroot) are absorbed, concentrated in saliva, reduced by oral bacteria into nitrite, and further converted to nitric oxide—particularly under hypoxic and acidic conditions.

This pathway is clinically relevant for three reasons:

It bypasses dysfunctional eNOS.

It becomes more active in ischemic tissues.

It explains why antiseptic mouthwash can blunt blood pressure–lowering effects of nitrate-rich diets.

Clinical trials demonstrate modest but consistent reductions in systolic blood pressure (often 4–8 mmHg) with sustained dietary nitrate intake. While not a replacement for pharmacotherapy, this pathway reinforces the concept that endothelial signaling can be nutritionally supported.

Aging reduces nitric oxide bioavailability through cumulative oxidative burden, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased ADMA levels. Telomere shortening and endothelial senescence further diminish regenerative capacity.

Importantly, oxidative stress is not merely a byproduct of disease—it is often a driver. NADPH oxidase upregulation, uncoupled eNOS, and mitochondrial leakage amplify superoxide generation. The result is a chronic shift from a nitric oxide–dominant state to a superoxide-dominant vascular phenotype.

Clinically, this manifests as:

Increased arterial stiffness

Isolated systolic hypertension

Reduced exercise tolerance

Endothelial-dependent vasodilation impairment

Interventions targeting redox balance—exercise, Mediterranean dietary patterns, smoking cessation—improve endothelial function more reliably than antioxidant supplementation alone, underscoring the complexity of redox signaling.

Nitric Oxide and the Metabolic Axis

Nitric oxide is deeply intertwined with metabolic regulation.

In skeletal muscle, NO enhances glucose uptake and mitochondrial efficiency. In adipose tissue, it modulates lipolysis and inflammation. In pancreatic islets, dysregulated NO contributes to β-cell stress. In the liver, impaired endothelial signaling worsens insulin resistance and dyslipidemia.

The vascular endothelium is therefore not merely a conduit—it is a metabolic organ. When NO signaling fails, metabolic flexibility declines. This insight helps explain why cardiometabolic disease clusters rather than occurring in isolation.

Therapeutic Modulation: Beyond Symptom Relief

Pharmacologic agents often restore NO signaling indirectly:

ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce oxidative stress and improve endothelial function.

Statins enhance eNOS expression and reduce NADPH oxidase activity.

SGLT2 inhibitors may improve vascular redox balance and reduce inflammation.

PDE-5 inhibitors amplify cGMP signaling downstream of NO.

Emerging research explores:

NO-releasing nanoparticles

BH4 stabilization strategies

ADMA-lowering interventions

Targeted sGC stimulators

Yet translational enthusiasm must be balanced with realism. Many experimental NO-delivery systems demonstrate promising preclinical results but face regulatory, dosing, and safety hurdles before widespread clinical application.

The Clinical Signal Before the Structural Lesion

Flow-mediated dilation (FMD) testing consistently demonstrates that endothelial dysfunction precedes detectable atherosclerosis. Coronary microvascular dysfunction may exist even when angiography appears normal.

This reframes early cardiovascular prevention. Rather than focusing solely on plaque burden, clinicians may increasingly consider endothelial health as an actionable biomarker of risk.

Practical interventions that improve NO signaling include:

Regular aerobic and resistance exercise

Dietary nitrate intake from natural sources

Weight reduction in insulin-resistant individuals

Blood pressure control

Smoking cessation

Sleep optimization

Periodontal health (preserving oral nitrate-reducing bacteria)

These measures converge on one biological goal: restoring nitric oxide availability.

Inflammation, Immunity, and Vascular Crosstalk

Chronic low-grade inflammation—driven by adipokines, cytokines, and gut-derived endotoxins—impairs endothelial NO production. Interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and CRP correlate with reduced endothelial function.

Conversely, nitric oxide suppresses adhesion molecule expression and leukocyte recruitment. Thus, endothelial dysfunction and inflammation are bidirectional amplifiers.

Cardiovascular disease may therefore be conceptualized as an inflammatory redox disorder with impaired signaling at its core.

Translational Frontiers: Promise and Prudence

Advanced biomaterials capable of sustained NO release are under development for vascular grafts and stents to prevent thrombosis and restenosis. Nanoparticle-based NO donors aim to deliver localized therapy while minimizing systemic hypotension.

However, nitric oxide biology is context-dependent. Excess NO in inflammatory states can combine with superoxide to generate peroxynitrite, contributing to oxidative injury. Therapeutic precision—rather than indiscriminate augmentation—is essential.

The future likely lies not in simply “boosting NO,” but in restoring physiological balance within redox signaling networks.

If cardiovascular disease begins with a failing signal, then prevention must begin with signal preservation.

Lipid management remains essential. Blood pressure control is critical. Glycemic regulation is indispensable. Yet beneath these risk factors lies a shared pathway: oxidative stress–mediated nitric oxide depletion.

The endothelium does not fail abruptly. It gradually shifts from a vasoprotective, anti-inflammatory phenotype to a pro-oxidant, pro-thrombotic state. Detecting and reversing that shift may represent one of the most powerful leverage points in modern cardiometabolic medicine.

Nitric oxide is more than a molecule—it is the language of vascular intelligence. When that language is disrupted, disease accelerates silently.

Reframing cardiovascular disease through the lens of nitric oxide biology integrates metabolism, inflammation, aging, and hemodynamics into a coherent molecular narrative. It highlights why lifestyle medicine works. It explains why metabolic disease and vascular disease are inseparable. And it clarifies why early intervention matters.

The blocked artery is the late manifestation.

The failing signal is the origin.

Protect the signal—and the structure may follow.

Author’s Note

As a physician trained in internal medicine I have long been fascinated by the central role of nitric oxide in vascular biology. Over the past three decades, nitric oxide has evolved from a biochemical curiosity to one of the most important signaling molecules in cardiovascular medicine. Yet despite the volume of research, its clinical implications are often underappreciated outside specialized circles.

This article was written to bridge that gap — to connect molecular mechanisms such as eNOS coupling, oxidative stress, and redox signaling with practical cardiovascular prevention strategies. The goal is not merely to describe nitric oxide biology, but to place it within the broader framework of endothelial function, cardiometabolic disease, and translational therapeutics.

The discussion integrates findings from contemporary peer-reviewed literature, including mechanistic reviews and emerging work on nanomaterial and biomaterial-based delivery systems. While the therapeutic potential of nitric oxide modulation is promising, it is equally important to recognize the complexity of its regulation and the limitations of current interventions.

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of global mortality. Understanding nitric oxide is not an academic exercise — it is central to how we conceptualize prevention, vascular repair, and metabolic health in the 21st century.

I hope this synthesis encourages clinicians, researchers, and informed readers alike to view cardiovascular disease not only as structural pathology, but as a modifiable signaling imbalance — one increasingly within our capacity to correct.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Statin Therapy and Dementia Risk: A Critical Review of Current Evidence | DR T S DIDWAL

Your Body Fat Is an Endocrine Organ—And Its Hormones Shape Your Heart Health | DR T S DIDWAL

hsCRP Explained: What Inflammation Means for Your Heart | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Abu-Soud, H. M., Camp, O. G., Ramadoss, J., Chatzicharalampous, C., Kofinas, G., & Kofinas, J. D. (2025). Regulation of nitric oxide generation and consumption. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 21(3), 1097–1109. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.105016

Carlström, M., Weitzberg, E., & Lundberg, J. O. (2024). Nitric oxide signaling and regulation in the cardiovascular system: Recent advances. Pharmacological Reviews, 76(6), 1038–1062. https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.124.001060

Gonzalez, M., Clayton, S., Wauson, E., Christian, D., & Tran, Q.-K. (2025). Promotion of nitric oxide production: Mechanisms, strategies, and possibilities. Frontiers in Physiology, 16, 1545044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2025.1545044

Naderian, R., Nazari, M. A., Meybodi, T. E., & et al. (2026). Redox signaling in the heart and brain: The roles of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in disease and therapy. Metabolic Brain Diseases, 41, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-025-01775-8

Nunes, R. S., Mariano, K. C. F., Pieretti, J. C., dos Reis, R. A., & Seabra, A. B. (2025). Innovative nitric oxide-releasing nanomaterials: Current progress, trends, challenges, and perspectives in cardiovascular therapies. Nitric Oxide, 156, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2025.03.004

Sun, J., Wang, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, F., Tong, J., Gao, R., Guo, X., Sun, D., & Wei, Y. (2025). Nitric oxide in biomaterial-based therapies for coronary heart disease: Mechanistic insights, current advances, and translational prospects. Biomaterials Research, 29, 0267. https://doi.org/10.34133/bmr.0267

Venkatesan, S., Smirne, C., Aquino, C. I., Surico, D., Remorgida, V., Ola Pour, M. M., Pirisi, M., & Grossini, E. (2026). Nitric oxide signaling in cardiovascular physiology and pathology: Mechanisms, dysregulation, and therapeutic frontiers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020629