Beyond Glucose: Lipotoxicity as the Central Mechanism of Metabolic Disease

Beyond glucose control, discover how toxic lipids damage the pancreas, heart, kidneys, and muscle—reshaping our understanding of metabolic disease.

METABOLISMDIABETES

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/16/202613 min read

For decades, metabolic disease was framed primarily as a disorder of glucose. Elevated blood sugar, defined type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), glycated haemoglobin-guided therapy, and treatment success were measured in milligrams per deciliter. Yet a deeper metabolic disturbance has been unfolding beneath the surface—one not visible on a glucometer. Increasing evidence suggests that long before hyperglycemia becomes clinically apparent, cells in the liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, kidney, and heart are already accumulating toxic lipid intermediates that silently disrupt cellular signaling and energy homeostasis (Chen et al., 2025; Cheng et al., 2025).

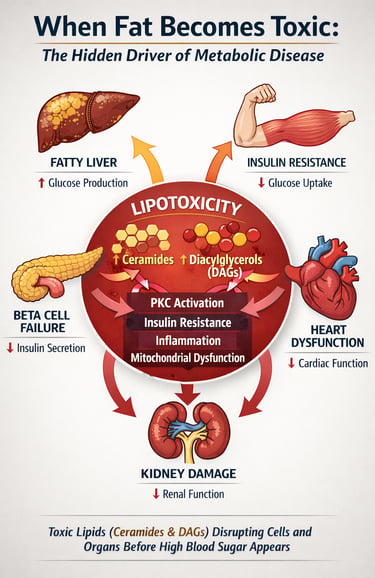

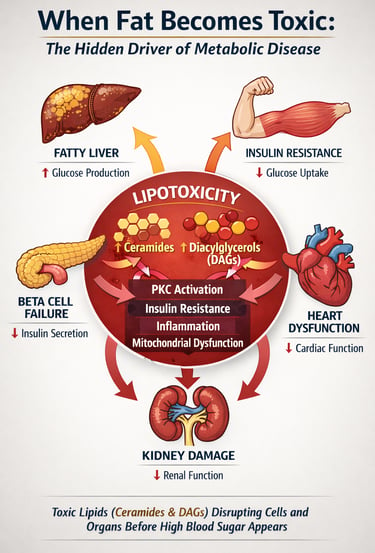

This process, known as lipotoxicity, occurs when fatty acid influx exceeds a cell’s capacity for safe oxidation or storage. Rather than remaining inert, excess lipids are converted into bioactive species such as diacylglycerols (DAGs) and ceramides, which directly impair insulin signaling, activate inflammatory pathways, and trigger mitochondrial dysfunction (Cheng et al., 2025). In pancreatic β-cells, chronic lipid exposure accelerates apoptosis and loss of insulin secretory capacity; in skeletal muscle and liver, it promotes insulin resistance; in the kidney and heart, it drives progressive structural damage (Anumas & Inagi, 2025; Luong et al., 2025).

Emerging data now suggest that metabolic disease is not merely glucotoxic but fundamentally gluco-lipotoxic, reflecting the synergistic injury imposed by nutrient excess (Chen et al., 2025). Understanding lipotoxicity, therefore, represents more than a mechanistic curiosity—it may redefine how we diagnose, stratify, and treat chronic cardiometabolic disease in the modern era.

Clinical pearls

1. The "Storage Locker" Principle (Adipose vs. Ectopic Fat)

Scientific Tone: Lipotoxicity is primarily a failure of adipose tissue expandability. When subcutaneous fat reaches its storage limit or becomes dysfunctional, lipids spill over into "ectopic" sites (liver, heart, pancreas, kidneys), where they act as cellular toxins rather than energy reserves.

Patient Tone: Think of your fat cells like a storage locker. As long as the "junk" stays in the locker, your house stays clean. Lipotoxicity happens when the locker is full and the fat starts piling up in your kitchen (liver) or your fuse box (heart), where it starts breaking things.

2. Lipotoxicity as a "Pro-Drug" for Diabetes

Scientific Tone: In the pathogenesis of T2DM, chronic exposure to elevated non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) triggers a "double hit": it induces peripheral insulin resistance while simultaneously causing pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis via ER stress and ROS production.

Patient Tone: Diabetes isn't just about eating too much sugar; it’s about "drowning" your insulin-producing cells in fat. Over time, this fat overload doesn't just make your body ignore insulin; it actually starts killing the cells that make insulin in the first place.

3. The Kidney’s Hidden Burden

Scientific Tone: Renal lipotoxicity is a major driver of podocyte effacement and glomerular filtration barrier breakdown. Lipid droplets in the proximal tubules disrupt mitochondrial bioenergetics, leading to the tubulointerstitial fibrosis seen in chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Patient Tone: Your kidneys are highly sensitive filters that require massive amounts of energy to clean your blood. When fat builds up in these filters, it’s like pouring grease down a delicate drain—it clogs the system and damages the "machinery" (mitochondria) the kidney needs to stay powered up.

4. Why SGLT2 Inhibitors are "Cellular Housekeepers"

Scientific Tone: Beyond their glucosuric effect, SGLT2 inhibitors mitigate lipotoxicity by promoting lipophagy (the degradation of lipid droplets) and shifting myocardial metabolism toward ketone body utilization, which is a more oxygen-efficient fuel source for the lipotoxic heart.

Patient Tone: Modern medications like SGLT2 inhibitors do more than just lower blood sugar. They act like a "cleaning crew" for your cells, helping your body burn off the toxic fat trapped inside your heart and kidneys and switching your "engine" to a cleaner-burning fuel.

5. The "TOFI" Risk (Thin Outside, Fat Inside)

Scientific Tone: BMI is a poor surrogate for lipotoxic risk. Normal-weight obesity (low BMI but high visceral/ectopic fat) can lead to severe metabolic dysfunction because the lack of healthy subcutaneous storage space forces lipids into vital organs even at low total body weights.

Patient Tone: You can’t always judge metabolic health by the scale. Some people look thin on the outside but are "marbled" with fat on the inside. Because they don't have much room to store fat under their skin, even a small amount of weight gain goes straight to their organs, making them just as at-risk as someone who is visibly overweight.

Lipotoxicity: When Fat Becomes Toxic

Lipotoxicity refers to the cellular dysfunction and damage caused by excessive lipid accumulation in tissues that aren't specialized for fat storage. While adipose tissue is designed to handle large amounts of triglycerides and fatty acids, organs like the pancreas, kidneys, and heart are not.

When free fatty acids exceed the cell's capacity for oxidation and storage, they accumulate in the form of lipid droplets and trigger several harmful pathways:

Mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired energy production

Endoplasmic reticulum stress and protein misfolding

Inflammation and oxidative stress

Apoptosis (programmed cell death)

Insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction

The concept of lipotoxicity has evolved significantly. It's no longer viewed as a simple matter of "too much fat in cells." Instead, modern research recognizes pan-lipotoxicity—a complex, organ-specific phenomenon where different types of lipids cause different types of damage in different tissues.

Study 1: Lipotoxicity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—A New Perspective

Chen et al. (2025) present a comprehensive review highlighting lipotoxicity as a central mechanism in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They argue that traditional glucose-centric models overlook the toxic impact of chronic lipid accumulation in metabolic tissues. Excess circulating free fatty acids infiltrate organs not specialized for fat storage, leading to cellular dysfunction and progressive metabolic failure.

Pancreatic β cells are identified as particularly susceptible to lipid-induced injury. Prolonged exposure to elevated fatty acids impairs glucose sensing and reduces glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Over time, lipotoxic stress promotes β-cell apoptosis, resulting in irreversible loss of insulin-producing capacity. This decline in functional β-cell mass accelerates the transition from insulin resistance to overt diabetes.

Beyond the pancreas, lipid deposition in skeletal muscle and liver further exacerbates metabolic dysfunction. Intramyocellular and intrahepatic lipids disrupt insulin signaling pathways, contributing to systemic insulin resistance. As tissues become less responsive to insulin, compensatory hyperinsulinemia develops. Elevated insulin levels, in turn, stimulate further lipid synthesis and storage, reinforcing a self-perpetuating cycle of lipotoxicity and β-cell deterioration.

Overall, the review positions lipotoxicity not merely as a secondary phenomenon but as a fundamental driver of T2DM progression. Targeting lipid metabolism and mitochondrial health may therefore be essential for developing more effective, disease-modifying diabetes therapies.

Study 2: Pan-Lipotoxicity—A Paradigm Shift in Cellular Pathology

Cheng et al. (2025) introduced the concept of pan-lipotoxicity, redefining lipotoxicity as a heterogeneous, system-wide process rather than a single uniform mechanism. Their work emphasizes that different lipid species—including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), cholesterol, lysophospholipids, and oxidized lipids—induce distinct forms of cellular injury through unique molecular pathways. Importantly, lipotoxic effects are highly tissue-specific; the same lipid species may trigger different pathological responses in pancreatic β cells, renal cells, hepatocytes, cardiomyocytes, or neurons.

Pan-lipotoxicity exerts multi-organ consequences. In the nervous system, it contributes to neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction. In the vasculature, it promotes endothelial dysfunction and accelerates atherosclerosis. In the liver, lipid overload drives steatosis and progression toward fibrosis. In the kidneys, ectopic lipid deposition damages glomerular structures, while in the heart, it contributes to myocardial dysfunction and heart failure.

Mechanistically, the study highlights the role of lipid sensing through toll-like receptors (TLRs), CD36, and other pattern recognition receptors that activate innate immune signaling pathways. Concurrently, lipid peroxidation generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), amplifying oxidative stress and cellular injury.

Overall, pan-lipotoxicity underscores the need for integrated, multi-organ therapeutic strategies, as targeting lipid metabolism via toll-like receptors (TLRs), CD36, and other pattern recognition receptors, which activate innate immune signalling in one tissue, may have systemic implications.c Kidney Disease—Mechanisms and Mitigation

Study 3 Lipotoxicity as a Driver of Kidney Disease

Anumas & Inagi (2025 ) highlight lipotoxicity as a critically underrecognized contributor to chronic kidney disease (CKD). Although diabetes and hypertension are traditionally viewed as the primary drivers of CKD, accumulating evidence shows that ectopic lipid deposition within renal tissue significantly accelerates disease progression. Lipid overload affects multiple renal compartments, including glomerular podocytes and endothelial cells, where lipid accumulation disrupts filtration barrier integrity. In the proximal tubules, lipotoxicity impairs nutrient reabsorption and cellular energy balance. Lipid-induced inflammation promotes interstitial fibrosis, while mitochondrial dysfunction reduces the energy supply required for effective filtration and cellular repair.

The authors also review current pharmacological strategies that may mitigate renal lipotoxicity. Statins lower cholesterol synthesis and exert anti-inflammatory effects beyond lipid reduction. GLP-1 receptor agonists improve insulin sensitivity and reduce hepatic lipid output, indirectly decreasing circulating free fatty acids that accumulate in the kidneys. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce renal lipid peroxidation and enhance mitochondrial autophagy, helping clear damaged mitochondria. Thiazolidinediones improve systemic lipid handling by enhancing insulin sensitivity and promoting healthier adipose tissue expansion.

Importantly, the study emphasizes that kidney protection extends beyond glycemic control. Effective CKD management requires integrated strategies targeting lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial health to slow disease progression and preserve renal function.

Study 4: Biomarker Identification—Unlocking Diagnostic Precision

A major obstacle in advancing lipotoxicity research has been the inability to directly measure toxic lipid injury in living patients. While circulating lipid levels and hepatic steatosis can be assessed clinically, lipotoxic damage within pancreatic β cells, renal podocytes, or cardiac myocytes remains largely invisible. This diagnostic gap has limited early detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic targeting of lipotoxicity-driven organ disease.

To address this challenge, Nie et al.(2024) applied advanced bioinformatic approaches to identify gene and protein biomarkers specifically associated with lipotoxicity-related diabetic nephropathy. Their integrative analyses revealed biomarker signatures linked to key biological pathways, including lipid metabolism and fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress responses, mitochondrial function and autophagy, inflammatory signaling, and apoptosis regulation. Collectively, these pathways reflect the core cellular processes disrupted by chronic lipid overload.

Clinically, such biomarkers hold significant promise. They could help identify patients at the highest risk for lipotoxicity-driven chronic kidney disease, enable monitoring of responses to therapies targeting lipid toxicity, and improve the prediction of disease progression. Importantly, biomarker-based stratification may also enhance clinical trial design by selecting patients most likely to benefit from anti-lipotoxic interventions.

Overall, this work represents an important step toward precision medicine in diabetes and kidney disease, shifting management from generic algorithms to individualized care based on underlying lipotoxicity burden.

Study 5: Cardiac Lipotoxicity—An Emerging Therapeutic Target

The Diabetic Heart and Lipotoxicity

According to Luong et al. (2025), individuals with diabetes have a 2–4-fold higher risk of developing heart failure, even when coronary artery disease and hypertension are accounted for. This observation has led to growing recognition of cardiac lipotoxicity as a central mechanism in diabetic heart disease. In the setting of chronic metabolic overload, excess circulating fatty acids are taken up by cardiomyocytes beyond their oxidative capacity. When mitochondrial β-oxidation becomes saturated, surplus fatty acids are diverted into triglyceride synthesis and stored as intracellular lipid droplets.

Over time, this adaptive storage mechanism becomes maladaptive. Lipid droplet–associated proteins may become dysfunctional, and toxic lipid intermediates accumulate. Saturated fatty acids promote lipid peroxidation and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to mitochondrial damage and reduced ATP production. Energy deficiency impairs excitation–contraction coupling, while altered calcium handling disrupts myocardial relaxation and contractility. Early manifestations typically include diastolic dysfunction, reflecting impaired relaxation, which may later progress to systolic dysfunction as contractile tissue is lost.

In parallel, oxidative stress and toxic lipid species trigger cardiomyocyte apoptosis, structural remodeling, and electrical instability, increasing arrhythmia risk.

Overall, cardiac lipotoxicity represents a mechanistically distinct contributor to diabetic cardiomyopathy. Targeting myocardial lipid metabolism and improving metabolic flexibility may offer promising strategies to prevent heart failure in patients with diabetes.

Integrating the Research: A Unified Understanding of Lipotoxicity

These five studies paint a coherent picture: lipotoxicity is a systemic phenomenon affecting virtually every organ, driven by excessive lipid accumulation and impaired lipid metabolism, manifesting as pancreatic dysfunction, insulin resistance, kidney disease, and cardiac failure.

The research trajectory is clear: we're moving from treating lipotoxicity as a secondary consequence of diabetes to recognizing it as a primary mechanism that drives disease across multiple organ systems.

Mechanistic points:

1️⃣ Ceramides and DAGs Are the Real Toxic Lipids

Not all intracellular fat is harmful. Diacylglycerols (DAGs) activate PKC isoforms, causing inhibitory serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, while ceramides block Akt signaling and promote apoptosis. These bioactive lipid intermediates—not triglycerides—drive insulin resistance and cellular dysfunction.

2️⃣ Lipotoxicity Impairs Insulin Signaling at the Molecular Level

PKC activation and ceramide accumulation disrupt the PI3K–Akt pathway, reducing glucose uptake in muscle and increasing hepatic glucose output. This converts lipid overload directly into metabolic dysfunction.

3️⃣ T2DM Is Better Described as “Gluco-Lipotoxic”

While lipotoxicity is a major driver, type 2 diabetes results from the interaction of lipid excess, chronic hyperglycemia, inflammation, and genetic susceptibility. Calling it purely a lipotoxic disease oversimplifies a multifactorial process.

4️⃣ The Liver–Muscle–Beta Cell Axis Forms a Vicious Cycle

Hepatic lipid overproduction → muscle DAG/ceramide accumulation → insulin resistance → compensatory hyperinsulinemia → beta cell lipotoxic stress → progressive beta cell failure. This self-amplifying loop sustains disease progression.

5️⃣ Lipotoxicity Is a Systemic, Multi-Organ Mechanism

Beyond glucose control, ectopic lipid deposition drives dysfunction in the pancreas, kidney, and heart. Effective therapy must target lipid metabolism, mitochondrial health, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signaling simultaneously.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lipotoxicity

Q1: Is lipotoxicity the same as being overweight or obese?

A: No. While obesity increases lipotoxicity risk, they're not synonymous. Lean individuals can develop lipotoxicity if they have impaired lipid metabolism, poor mitochondrial function, or a genetic predisposition to lipid accumulation in specific tissues. Conversely, some obese individuals have preserved insulin sensitivity and minimal lipotoxicity.

Q2: Can lipotoxicity be reversed?

A: Yes, in many cases. Studies show that improving insulin sensitivity, enhancing mitochondrial function, and reducing circulating free fatty acids can reverse lipid accumulation in pancreatic, renal, and cardiac tissues. The degree of reversal depends on how much permanent damage has occurred.

Q3: How does lipotoxicity relate to inflammation?

A: Lipotoxicity and inflammation are intimately connected. Accumulated lipids activate pattern recognition receptors like TLRs and CD36, triggering NF-κB signaling and inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β). This lipid-induced inflammation amplifies cellular damage.

Q4: Can I reduce lipotoxicity through diet alone?

A: Diet is crucial. Reducing saturated fat intake, increasing fiber, and improving insulin sensitivity through weight loss all reduce lipotoxicity. However, some people benefit from medications that enhance lipid oxidation or reduce lipid accumulation in specific tissues.

Q5: Are there blood tests for lipotoxicity?

A: Traditional lipid panels don't directly measure lipotoxicity. However, emerging biomarkers identified in research—including specific lipid species (diacylglycerols, ceramides), mitochondrial dysfunction markers, and inflammatory mediators—may soon enable clinical lipotoxicity assessment.

Q6: How do SGLT2 inhibitors help with lipotoxicity?

A: SGLT2 inhibitors reduce circulating glucose and increase glucose excretion, improving insulin sensitivity. More importantly, they promote mitochondrial health, reduce oxidative stress, and enhance autophagy, all of which reduce cellular lipid accumulation and mitigate lipotoxicity.

Q7: What's the difference between healthy and pathological fat accumulation?

A: Healthy lipid accumulation supplies energy during fasting and supports cell membrane integrity. Pathological lipotoxicity occurs when lipid accumulation exceeds the cell's capacity to use, store, or clear the lipids, triggering cellular dysfunction and death.

Key Takeaways: What You Need to Know

Lipotoxicity Is a Primary Disease Driver: Rather than just a consequence of metabolic dysfunction, excessive lipid accumulation actively drives disease progression in diabetes, kidney disease, and heart disease.

Pan-Lipotoxicity Affects Multiple Organs: Different lipid species damage different tissues through distinct mechanisms. A comprehensive approach must target lipotoxicity across multiple organ systems.

Type 2 Diabetes as a Lipotoxicity Disease: Pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance both stem from lipid-induced cellular damage. Effective diabetes treatment must address lipotoxicity, not just glucose control.

Kidneys Are Vulnerable to Lipotoxicity: Renal lipid accumulation is a major, modifiable driver of CKD progression. Current medications (statins, GLP-1 agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors) provide renoprotection partly through anti-lipotoxicity mechanisms.

Biomarkers Enable Precision Medicine: Emerging lipotoxicity biomarkers will enable early diagnosis, risk stratification, and personalized treatment planning.

The Diabetic Heart Is Particularly Vulnerable: Cardiac lipotoxicity is a major—and often overlooked—driver of heart failure in diabetic patients. Myocardial lipid metabolism represents a critical therapeutic target.

Multiple Intervention Points Exist: From enhancing fatty acid oxidation to promoting lipophagy to reducing lipid uptake, multiple pharmacological strategies can mitigate lipotoxicity.

Current Medications Partly Work Through Anti-Lipotoxicity Mechanisms: Drugs like GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors provide benefits beyond glucose lowering—they actively reduce cellular lipid accumulation and restore mitochondrial function.

Practical Implications: What This Means for Patients

If you have type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease, understanding lipotoxicity has important implications:

Dietary Modifications: Reduce saturated fat intake, increase dietary fiber, and focus on whole grains, vegetables, and lean proteins. These changes reduce circulating free fatty acids and decrease lipid accumulation in vulnerable tissues.

Physical Activity: Exercise enhances mitochondrial function, improves insulin sensitivity, and increases fatty acid oxidation, all of which reduce lipotoxicity.

Weight Management: Even modest weight loss (5-10%) significantly reduces hepatic lipid content and pancreatic lipotoxicity.

Medication Optimization: If you're on medications like statins, metformin, GLP-1 agonists, or SGLT2 inhibitors, recognize that they're protecting you from lipotoxicity in ways beyond their primary mechanism. Adherence is crucial.

Regular Monitoring: Work with your healthcare provider to monitor not just glucose and blood pressure, but also lipid levels, kidney function, and cardiac health. These measures reflect the lipotoxicity burden.

Author’s Note

Metabolic disease is often reduced to numbers—glucose levels, HbA1c percentages, LDL concentrations. Yet beneath these measurable parameters lies a deeper biological narrative: the silent accumulation of toxic lipid intermediates within cells not designed to store them. This chapter was written to shift the lens from surface biomarkers to underlying cellular mechanisms—specifically, the role of lipotoxicity as a unifying driver of multi-organ dysfunction.

The concept of lipotoxicity is not new, but its clinical implications are rapidly evolving. Recent research suggests that bioactive lipid species such as ceramides and diacylglycerols are not passive byproducts of overnutrition; they actively disrupt insulin signaling, impair mitochondrial function, trigger inflammation, and accelerate organ damage. These processes begin long before overt hyperglycemia is detected, challenging the traditional glucose-centric model of metabolic disease.

At the same time, it is important to maintain scientific balance. Type 2 diabetes and related cardiometabolic disorders are multifactorial. Genetics, inflammation, glucotoxicity, environmental exposures, and lifestyle patterns intersect in complex ways. Lipotoxicity represents a powerful and often underappreciated mechanism within this network—not the sole cause, but a central contributor.

My goal in this chapter is not to oversimplify, but to integrate emerging mechanistic insights with clinical relevance. By understanding how excess lipid flux reshapes cellular biology across the liver, muscle, pancreas, kidney, and heart, we move closer to therapies that address root causes rather than downstream consequences.

Ultimately, preventing metabolic disease requires more than glucose control—it requires restoring metabolic flexibility, mitochondrial health, and cellular resilience.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with qualified healthcare professionals before making changes to your health regimen or treatment plan. The information presented reflects current research as of February 2026 and may be subject to change as new evidence emerges.

Related Articles

References

Anumas, S., & Inagi, R. (2025). Mitigating lipotoxicity: A potential mechanism to delay chronic kidney disease progression using current pharmacological therapies. Nephrology, 30(7), e70098. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.70098

Chen, B., Li, T., Wu, Y., Song, L., Wang, Y., Bian, Y., Qiu, Y., & Yang, Z. (2025). Lipotoxicity: A new perspective in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 18, 1223–1237. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S511436

Cheng, Y., Shao, S., Wang, Z., et al. (2025). From lipotoxicity to pan-lipotoxicity. Cell Discovery, 11, 27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-025-00787-z

Luong, T. V. T., Yang, S., & Kim, J. (2025). Lipotoxicity as a therapeutic target in the type 2 diabetic heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 201, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2025.02.010

Nie, H., Yang, H., Cheng, L., & Yu, J. (2024). Identification of lipotoxicity-related biomarkers in diabetic nephropathy based on bioinformatic analysis. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2024, Article 5550812. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5550812