Why Fructose Makes You Overeat: How It Disrupts the Brain’s Satiety and Reward Signals

Learn how fructose alters brain satiety and reward signaling, suppresses leptin and PYY, and drives overeating independent of willpower or calories.

NUTRITIONMETABOLISM

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/10/202612 min read

Most people assume overeating is a failure of willpower—a behavioral lapse corrected by discipline or calorie counting. Yet mounting evidence suggests a far more unsettling reality: certain sugars biologically disable the brain’s ability to recognize fullness. Among them, fructose stands out as uniquely disruptive. Unlike glucose, which is widely metabolized and tightly regulated, fructose follows a hepatic-centric metabolic pathway that bypasses key hormonal and neural feedback systems involved in appetite control (Nakagawa & Johnson, 2025; Agarwal et al., 2024).

When fructose is consumed, it elicits only a weak insulin response and fails to adequately stimulate leptin and peptide YY—two critical hormones that signal satiety to the hypothalamus (Flores Monar et al., 2025). As a result, the brain receives an incomplete message: energy has entered the body, but the signal to stop eating never fully arrives. At the same time, fructose alters dopaminergic reward signaling, creating a mismatch between caloric intake and perceived satisfaction—food is consumed, yet reward remains blunted, driving continued intake (Flores Monar et al., 2025).

Compounding this problem, fructose metabolism rapidly increases hepatic de novo lipogenesis and uric acid production, processes linked to hypothalamic inflammation and impaired appetite regulation (Agarwal et al., 2024; Baharuddin, 2025). Importantly, these effects occur independent of body weight, meaning even lean individuals may experience fructose-induced appetite dysregulation and metabolic stress (Tappia et al., 2026).

Together, these mechanisms challenge the traditional narrative of overeating. The issue is not simply how much we eat, but how specific nutrients manipulate the brain’s satiety and reward circuitry at a biochemical level. Understanding fructose’s role in this process is essential to understanding why modern diets so reliably promote chronic overeating and metabolic disease.

Clinical Pearls

1. The "Energy Depletion" Paradox

Scientific: Fructose metabolism in the liver is unregulated by phosphofructokinase. This leads to rapid phosphorylation of fructose, causing transient ATP depletion and an increase in uric acid production. This intracellular "energy crisis" triggers oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.

Fructose is a "gas guzzler." While most sugars give your cells energy, fructose actually drains your liver’s "batteries" to process it. This process creates uric acid—the same stuff that causes gout—which acts like a smoke signal telling your body to store fat and raise your blood pressure.

creates uric acid—the same stuff that causes gout—which acts like a smoke signal telling your body to store fat and raise your blood pressure.

2. The "Insulin-Independent" Trap

Scientific: Unlike glucose, fructose does not require insulin for entry into hepatocytes (via GLUT5/GLUT2 transporters). Consequently, it does not stimulate the secretion of leptin (the satiety hormone) or suppress ghrelin (the hunger hormone), leading to a failure of homeostatic appetite regulation.

Fructose bypasses your "off" switch. Your body has a built-in sensor for bread or potatoes that tells your brain you’re full. Fructose sneaks past that sensor. This is why you can drink a large soda or eat a tub of sweetened yogurt and still feel hungry ten minutes later—your brain literally didn't "see" the calories.

3. De Novo Lipogenesis (DNL) & "Skinny Fat" Risk

Scientific: High fructose flux into the liver directly activates the SREBP-1c and ChREBP transcription factors. This creates a "fat factory" effect where sugar is converted into triglycerides even in the absence of a caloric surplus, contributing to visceral adiposity and ectopic fat.

It’s a sugar-to-fat machine. Your liver is incredibly efficient at turning fructose into belly fat. This is why some people look "thin" but have high cholesterol or a fatty liver. You aren't just "eating" fat; your liver is manufacturing it directly from the hidden sugars in your diet.

4. The Endothelial "Corrosion"

Scientific: Fructose-induced hyperuricemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). This reduction in nitric oxide—a potent vasodilator—leads to systemic vasoconstriction, arterial stiffness, and the "vascular abnormalities" cited in 2026 cardiac research.

Fructose hardens your pipes. To keep your heart healthy, your blood vessels need to be flexible and "springy." High fructose intake creates a chemical reaction that stiffens these vessels, making your heart work much harder to pump blood. This can lead to high blood pressure long before you notice any weight gain.

5. The Fiber "Lattice" Defense

Scientific: The rate of fructose delivery to the liver (flux) determines its toxicity. Consumption of fructose via whole fruit provides a fibrous matrix that slows intestinal absorption and maintains the integrity of the intestinal barrier, preventing the "leaky gut" inflammation often seen with liquid fructose.

Nature provides the antidote. When you eat an apple, the fiber acts like a slow-release gate, letting the sugar into your system one drop at a time so your liver can handle it. When you drink apple juice, you’re hitting your liver with a "flood" that it can’t manage, forcing it to turn that sugar into fat immediately.

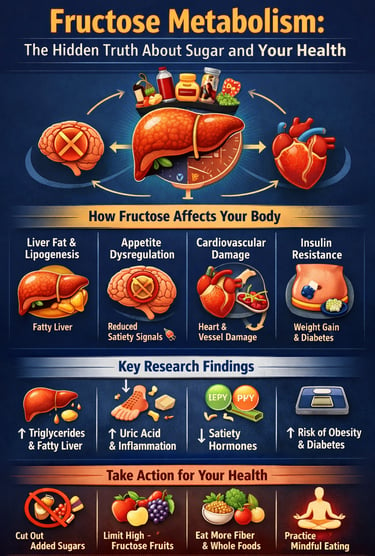

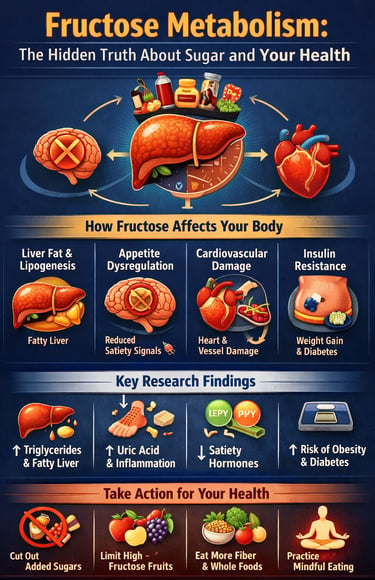

Fructose Metabolism: The Hidden Truth About Sugar and Your Health

Understanding Fructose Metabolism: The Biochemical Basics

Glucose metabolism occurs throughout your body. Your cells have receptors that signal when they've had enough glucose, creating a natural feedback loop that prevents overconsumption. Fructose, however, bypasses most of these regulatory mechanisms. Instead, it's primarily processed in your liver, where it's converted into lipids (fats) through a process called lipogenesis—and this is where problems begin.

Unlike glucose, fructose doesn't trigger insulin release as efficiently. This means your brain's appetite regulation centers don't receive the normal "I'm full" signals. You can consume massive quantities of fructose without feeling satiated, leading to chronic overconsumption and excessive calorie intake.

This fundamental difference in how your body processes fructose versus glucose is the cornerstone of understanding why a high-fructose diet is so metabolically damaging.

Study 1: Mindful Eating and Fructose's Effects on Appetite and Brain Function

This study by Flores Monar et al (2025) provides compelling evidence that fructose metabolism directly interferes with your brain's ability to regulate hunger and fullness. The research demonstrates that high fructose consumption suppresses the production of satiety hormones—particularly leptin and peptide YY—which normally signal your brain when you've eaten enough.

Most alarmingly, the study found that fructose consumption doesn't trigger the same dopamine response as glucose, making it less satisfying neurologically. This combination creates a "perfect storm" for overeating: you don't feel full or satisfied, yet you keep eating more.

The research also examined how mindful eating practices might counteract these effects, finding that conscious consumption strategies can help mitigate the worst effects of dietary fructose.

Key Takeaways

Fructose metabolism bypasses normal appetite regulation mechanisms

High fructose diets suppress critical satiety hormone production

Mindful eating shows promise as a behavioral intervention strategy

Brain function is directly impacted by fructose consumption patterns

Study 2: Cardiac Dysfunction and Vascular Abnormalitie

This study by Tappia et al.(2026) is perhaps the most concerning recent discovery: high fructose consumption doesn't just affect your weight or metabolic markers—it directly damages your heart and blood vessels.

The research demonstrates that fructose metabolism leads to increased triglyceride production in the liver, which subsequently accumulates in arterial walls and cardiac tissue. This creates a cascade of problems: endothelial dysfunction (damage to blood vessel linings), hypertension (high blood pressure), and ultimately cardiac dysfunction.

The mechanism is particularly insidious because it occurs independent of weight gain. You can be relatively thin and still experience significant vascular abnormalities from excessive fructose consumption—this isn't simply an obesity problem, it's a metabolic toxicity issue.

Key Takeaways

Fructose metabolism directly causes cardiac dysfunction independent of obesity

High fructose consumption induces vascular abnormalities and endothelial dysfunction

Triglyceride elevation from fructose drives cardiovascular disease risk

Even lean individuals face significant cardiac risk from excessive dietary fructose

Study 3: The Missing Link in Obesity Research

This research by Nakagawa & Johnson (2025) argues that the scientific community has underestimated fructose's role in obesity. While most obesity discussions focus on overall calorie consumption and fat intake, the evidence increasingly suggests that fructose metabolism is a primary driver of weight gain independent of total calories consumed.

The study highlights that fructose consumption promotes de novo lipogenesis (creation of new fat molecules) far more efficiently than other carbohydrates. Additionally, fructose increases uric acid production, which impairs the enzyme responsible for mitochondrial function—essentially damaging the "power plants" of your cells, reducing overall metabolic efficiency.

Key Takeaways

Fructose consumption drives obesity through unique metabolic pathways

De novo lipogenesis from fructose is the primary fat-storage mechanism

Uric acid elevation from fructose impairs cellular metabolism

Conventional calorie-counting misses the unique metabolic damage from fructose

Study 4: Metabolic Syndrome and Treatment Strategies

Metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia—is increasingly recognized as being driven by high fructose consumption.

The research by Rahimi & Ghazi Zadeh (2025) identifies the mechanisms by which fructose triggers each component of metabolic syndrome: it increases liver fat, elevates triglycerides, drives insulin resistance, and promotes visceral adiposity (dangerous belly fat).

Importantly, the study evaluated various dietary interventions and treatment strategies. The most effective approaches involve not just reducing total sugar, but specifically targeting fructose reduction while maintaining adequate complex carbohydrate and dietary fiber intake.

Key Takeaways

High fructose consumption is a primary driver of metabolic syndrome development

Metabolic syndrome from fructose involves unique mechanisms at the liver level

Dietary intervention focusing on fructose elimination shows superior results

Complex carbohydrates and fiber help restore metabolic health

Study 5: Population-Based Evidence from Danish Cohort Research

Another large-scale population study by Trius-Soler et al.(2025) provides real-world evidence that different types of dietary sugars have dramatically different health impacts. The research followed thousands of Danish participants, categorizing their sugar consumption and tracking cardiometabolic outcomes.

The findings were striking: fructose consumption (particularly from added sugars and high-fructose corn syrup) was significantly associated with increased diabetes risk, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic dysfunction, while glucose consumption from whole foods and complex carbohydrates showed no such association.

This study provides crucial epidemiological evidence that it's not "sugar in general" that's problematic—it's specifically fructose that drives metabolic disease.

Key Takeaways

Population-based evidence confirms fructose's unique metabolic harm

Added fructose increases diabetes risk far more than glucose-based carbohydrates

Whole food carbohydrates maintain metabolic health despite carbohydrate content

Sugar type, not just sugar quantity, determines health outcomes

Study 6: The Molecular Mechanisms Behind Metabolic Damage

A comprehensive literature review by Agarwal et al.(2024) synthesized decades of research on fructose metabolism, revealing the molecular mechanisms by which dietary fructose causes metabolic dysfunction.

Key discoveries include:

Hepatic steatosis (fatty liver disease): Fructose metabolism in the liver generates excess acetyl-CoA, which is converted to fatty acids and stored as triglycerides. This is the primary mechanism driving non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), affecting over 25% of the global population.

Mitochondrial dysfunction: Fructose consumption impairs the function of mitochondria, your cells' energy-producing structures. This cascade effect reduces overall metabolic efficiency and contributes to metabolic syndrome.

Inflammation: High fructose diets increase inflammatory markers throughout your body, driving chronic disease development.

Key Takeaways

Fructose metabolism directly causes hepatic steatosis and fatty liver disease

Mitochondrial dysfunction from fructose reduces cellular energy production

Chronic inflammation from dietary fructose drives age-related disease

Multiple molecular pathways explain why fructose is metabolically toxic

Study 7: The Lipogenesis Connection to Metabolic Disorders

A detailed mechanistic study BY Baharuddin (2025) provides the most complete picture of how fructose consumption activates lipogenic pathways and creates metabolic disorder.

The research demonstrates that fructose metabolism specifically activates genes responsible for fat synthesis through a process involving ChREBP (carbohydrate response element-binding protein) and SREBP-1c (sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c). These molecular switches essentially tell your liver "make fat now."

Unlike glucose, which is distributed throughout your body and burned for energy, fructose is almost entirely processed by your liver, where it's preferentially converted to fatty acids rather than glucose. This explains why fructose consumption causes such severe hepatic lipogenesis and subsequent metabolic disorder.

The study also examined how different fructose sources (fruit juice, added sugars, high-fructose corn syrup) all activate these same lipogenic pathways, despite common claims that "fruit fructose is different."

Key Takeaways

Fructose metabolism activates specific fat-synthesis genes (ChREBP, SREBP-1c)

Hepatic lipogenesis from fructose is the primary metabolic damage mechanism

All fructose sources activate identical metabolic disorder pathways

Fruit fructose isn't metabolically different from added fructose

The Convergence of Evidence: What All These Studies Tell Us

When we examine these eight peer-reviewed studies together, a clear picture emerges: high fructose consumption is not a minor dietary concern. It's a primary driver of multiple metabolic diseases, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

The evidence is particularly compelling because it comes from multiple research perspectives:

Mechanistic studies explain exactly how fructose metabolism causes harm

Population studies confirm these mechanisms occur in real-world populations

Cardiac research reveals unexpected organ damage from fructose

Behavioral research shows why fructose consumption is so difficult to control

Most importantly, the research demonstrates that this isn't about being "weak-willed" or "lazy." Your body literally responds differently to fructose than to other carbohydrates. The mechanism is biochemical, not behavioral.

Practical Recommendations Based on the Research

Reduce or Eliminate Added Fructose

The evidence overwhelmingly supports minimizing added sugars, particularly high-fructose corn syrup and refined fructose. Check labels for these terms: "fructose," "corn syrup," "high-fructose corn syrup," and "agave nectar."

Reevaluate Your Fruit Consumption

While whole fruits contain fiber and phytonutrients, research shows that fruit juices and excessive whole fruit consumption can still activate lipogenic pathways. Focus on low-fructose fruits like berries while limiting high-fructose fruits like mangoes and watermelon.

Prioritize Metabolic Health Testing

Given the evidence of cardiac dysfunction and hepatic steatosis occurring independent of weight, consider requesting liver function tests, triglyceride panels, and uric acid measurements—even if you're at a healthy weight.

Practice Mindful Eating

As the Flores Monar study demonstrated, mindful eating practices can help overcome the appetite dysregulation caused by fructose metabolism.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is fruit bad for you?

A: Whole fruits contain fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients that processed fructose doesn't. The fiber content slows fructose absorption and activates different metabolic pathways. However, fruit juice and excessive whole fruit consumption (beyond 2-3 servings daily) may still activate lipogenic pathways.

Q: What about honey and agave?

A: Despite marketing claims, honey and agave nectar are primarily fructose and activate the same hepatic lipogenesis as refined fructose. They offer no metabolic advantage over regular sugar.

Q: Can I still have sweets on a low-fructose diet?

A: Yes, but choose carefully. Stevia, erythritol, and xylitol don't activate fructose metabolism pathways. However, avoid sugar alcohols in excess, as they can cause digestive distress.

Q: How quickly will I see health improvements?

A: Triglyceride reduction typically occurs within 2-4 weeks of fructose elimination. Liver fat reduction takes 8-12 weeks. Metabolic syndrome reversal can take 3-6 months. Appetite normalization often improves within 2-3 weeks as satiety hormones stabilize.

Q: Are artificial sweeteners better than sugar?

A: Most artificial sweeteners don't contain fructose, so they don't activate the same metabolic damage pathways. However, they may not be ideal for long-term use. Focus first on fructose elimination, then consider sweetener choice secondarily.

Q: What about people with genetic predispositions?

A: The research suggests fructose metabolism causes metabolic dysfunction in virtually all individuals, though the severity varies. Those with family histories of metabolic syndrome or cardiovascular disease should be especially vigilant about fructose consumption.

Author’s Note

This article was written to clarify a topic that is often oversimplified, misunderstood, or distorted by nutrition marketing and popular media: fructose metabolism. While “sugar” is frequently discussed as a single entity, the scientific evidence clearly shows that different sugars behave very differently in the human body. Fructose, in particular, follows unique metabolic pathways that have profound implications for liver health, cardiometabolic risk, appetite regulation, and long-term metabolic disease.

The goal of this piece is not to promote fear of food or to demonize all carbohydrates, but to present the current state of scientific evidence as accurately and transparently as possible. The conclusions drawn here are based on mechanistic studies, population data, and clinical research, with careful attention to how fructose affects human physiology independent of body weight or total calorie intake.

Where strong claims are made, they reflect areas where evidence has converged across multiple research domains. Where nuance exists—such as the role of whole fruits, dietary context, and individual variability—it is acknowledged. Nutrition science is complex, but complexity should not be an excuse for ambiguity when consistent biological signals are present.

This article is intended for clinicians, researchers, health professionals, and scientifically curious readers who want a deeper understanding of why metabolic diseases are rising and how dietary patterns contribute at the molecular and systemic levels. If it encourages more critical label reading, more informed dietary choices, or deeper discussion about metabolic health, it has served its purpose.

Science evolves, and so should our dietary frameworks. The evidence reviewed here suggests that reducing added fructose is not a trend—it is a rational, evidence-based strategy for protecting metabolic health.

.Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Feed Your Gut, Fuel Your Health: Diet, Microbiota, and Systemic Health | DR T S DIDWAL

What’s New in the 2025 Blood Pressure Guidelines? A Complete Scientific Breakdown | DR T S DIDWAL

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb: Which Diet is Best for Weight Loss? | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Agarwal, V., Das, S., Kapoor, N., Prusty, B., & Das, B. (2024). Dietary fructose: A literature review of current evidence and implications on metabolic health. Cureus, 16(11), e74143. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.74143

Baharuddin, B. (2025). The metabolic and molecular mechanisms linking fructose consumption to lipogenesis and metabolic disorders. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 69, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2025.06.042

Flores Monar, G. V., Sanchez Cruz, C., & Calderon Martinez, E. (2025). Mindful eating: A deep insight into fructose metabolism and its effects on appetite regulation and brain function. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2025, 5571686. https://doi.org/10.1155/jnme/5571686

Nakagawa, T., & Johnson, R. J. (2025). Do not overlook the role of fructose in obesity. Nature Metabolism, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-024-01198-2

Rahimi, K., & Ghazi Zadeh, S. (2025). The impact of high fructose consumption on metabolic syndrome: Dietary and treatment strategies for effective management. Clinical Reviews and Opinions, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5897/CRO2024.0128

Tappia, P., Garriock, E., Ramjiawan, B., & Moghadasian, M. (2026). High fructose consumption induces cardiac dysfunction and vascular abnormalities. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2025-0249

Trius-Soler, M., Bramming, M., Jensen, M. K., Tolstrup, J. S., & Guasch-Ferré, M. (2025). Types of dietary sugars and carbohydrates, cardiometabolic risk factors, and risk of diabetes: A cohort study from the general Danish population. Nutrition Journal, 24(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-025-01071-2