Weight Loss as Immunotherapy: The Science Behind Reversing Chronic Inflammation

Obesity fuels chronic inflammation and autoimmune risk. Learn how weight loss may function as immunotherapy to restore immune health

OBESITY

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.(Internal Medicine)

2/22/202616 min read

How Obesity Fuels Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disease

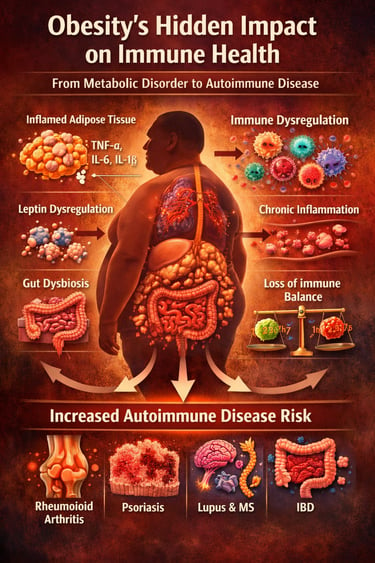

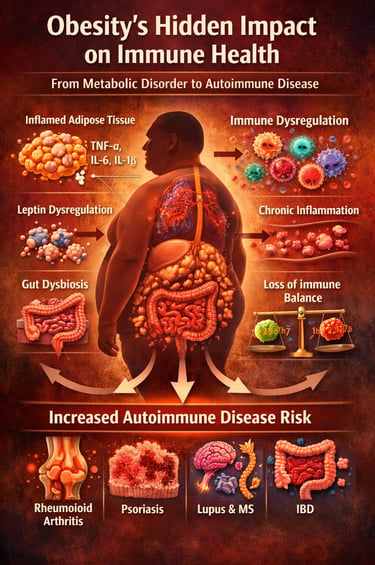

Obesity is no longer just a metabolic disorder—it is emerging as a powerful driver of immune dysregulation, chronic inflammation, and autoimmune disease risk. While the public conversation continues to focus on diabetes and heart disease, a quieter and potentially more devastating consequence is unfolding within the immune system itself. New large-scale cohort studies and mechanistic reviews published in 2025–2026 reveal that excess adipose tissue actively reprograms immune function, creating a persistent state of low-grade systemic inflammation that lowers the threshold for autoimmune activation (Jiang et al., 2025; Spatocco et al., 2026).

Far from being metabolically inert, adipose tissue acts as an endocrine and immune organ, releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, while the adipokine leptin amplifies autoreactive T-cell responses and suppresses regulatory immune pathways (Jiang et al., 2025). Prospective data from the UK Biobank demonstrate that clinically defined obesity significantly increases long-term incidence of rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (Xu et al., 2025). Real-world electronic health record analyses confirm this association across diverse populations using robust propensity score–matched cohort designs (Lin et al., 2026).

Meta-analytic evidence now quantifies what clinicians are observing: obesity confers a statistically significant elevation in autoimmune disease risk across multiple organ systems (Spatocco et al., 2026). In other words, the global obesity epidemic may be silently fueling an equally significant epidemic of immune-mediated inflammatory disease—with profound implications for prevention, screening, and long-term health strategy.

Clinical pearls

Scientific Perspective: Adipose tissue is not just a storage site for triglycerides; it is a bioactive endocrine organ. In obesity, adipocytes undergo hypertrophy and stress, triggering a "phenotypic switch" from anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages to pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. This creates a systemic "cytokine storm" at a low, chronic simmer.

Think of your body fat as a giant gland that talks to your immune system. When fat cells get too crowded, they start sending out "SOS" signals. These signals confuse your immune system, making it over-reactive and more likely to accidentally attack your own healthy tissues.

2. The "Lowered Threshold" Effect

Scientific Perspective: Elevated leptin levels in obesity act as a potent pro-inflammatory stimulus. Leptin directly activates Th1 cells while suppressing the T-regulatory (Treg) cells that normally prevent autoimmunity. This effectively lowers the biological threshold required to trigger an autoimmune flare.

Obesity acts like a volume knob for inflammation. It turns the "background noise" up so high that your body's natural "brakes"—the cells meant to keep you calm and healthy—can't do their job. This makes it much easier for a disease like Arthritis or Lupus to get started.

3. "Clinical Obesity" vs. The Scale

Scientific Perspective: According to Xu et al. (2025), the functional severity of obesity (metabolic health and physical mobility) is a stronger predictor of autoimmune risk than BMI alone. "Metabolically unhealthy" obesity carries a significantly higher immunological load than simple weight.

The number on the scale only tells part of the story. How your weight affects your movement, your energy, and your blood sugar matters more for your immune health than the size of your clothes. Being "fit-fat" is immunologically safer than being "unfit" at the same weight.

4. The Gut-Barrier Breach (Leaky Gut)

Scientific Perspective: Obesity-induced dysbiosis weakens the tight junctions of the intestinal epithelium. This "leaky gut" allows lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from bacteria to enter the bloodstream, a process called metabolic endotoxemia, which is a primary driver of systemic autoimmune activation.

Obesity can make the lining of your gut a bit "leaky." When tiny fragments of bacteria slip through that lining into your blood, your immune system goes on high alert. This constant state of "stranger danger" in your blood is a major reason why obesity leads to inflammatory diseases.

5. Weight Loss as "Immunotherapy"

Scientific Perspective: Recent data from Wang et al. (2025) suggests that significant weight loss via GLP-1 agonists or bariatric surgery doesn't just improve metabolism—it can lead to "immune remission." Reducing fat mass rapidly lowers TNF-α and IL-6 levels, potentially slowing the progression of autoimmune damage.

Losing weight isn't just about heart health or looking better; it's a form of medicine for your immune system. Shrinking fat cells is like taking an anti-inflammatory pill that works 24/7, helping to "cool down" the fire of an autoimmune disease.

6. The "Silent" Risk for Skin and Joints

Scientific Perspective: Mousavi et al. (2025) showed that obesity-linked inflammation is uniquely aggressive toward the skin (Psoriasis, Pemphigoid) and connective tissues. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-17 are particularly elevated in patients with high visceral adiposity.

We used to think obesity only affected your heart or liver, but the new science shows it’s a major trigger for skin conditions and joint pain. If you have itchy skin patches or stiff joints, your body might be reacting to the hidden inflammation coming from deep "belly fat."

The Mechanistic Foundation: How Obesity Hijacks the Immune System

Before examining population-level data, it is essential to understand why obesity promotes immune dysfunction. The most comprehensive mechanistic account comes from Jiang et al. (2025), whose annual review in the Annual Review of Pathology provides a granular molecular framework for immune dysregulation in obesity.

Adipose tissue—once considered metabolically inert—is now recognized as a dynamic endocrine and immune organ. In states of excess adiposity, adipose tissue undergoes profound remodeling. Adipocytes hypertrophy and become stressed, triggering a cascade of inflammatory signaling. Crucially, adipose tissue in obese individuals becomes infiltrated by pro-inflammatory immune cells, including M1-polarised macrophages, Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes, and natural killer cells, while simultaneously losing its regulatory immune populations such as Treg cells and M2 macrophages. This shift in immune balance creates a state of chronic, low-grade systemic inflammation.

The consequences are far-reaching. Elevated circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines—particularly tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and leptin—not only sustain local adipose inflammation but spill over into systemic circulation, priming immune cells throughout the body toward heightened reactivity. Leptin, the adipokine produced in proportion to fat mass, is particularly noteworthy: it acts on T cells and dendritic cells to promote pro-inflammatory responses while suppressing regulatory immune activity—essentially lowering the threshold for autoimmune activation.

Concurrently, obesity disrupts the gut microbiome (dysbiosis), compromises intestinal barrier integrity (contributing to "leaky gut"), and alters the composition and trafficking of lymphoid tissue. These changes collectively create an immunological milieu primed for the breakdown of self-tolerance—the very mechanism underlying autoimmune disease.

Key Takeaway — Jiang et al. (2025): Obesity induces a multisystem immune dysregulation through adipose tissue remodeling, cytokine imbalance, gut dysbiosis, and leptin-driven immune skewing, providing a mechanistic basis for increased autoimmune disease susceptibility across multiple organ systems.

Population-Level Evidence: The UK Biobank Perspective

Mechanistic insights gain their clinical weight when confirmed in large human populations. Xu et al. (2025), publishing in the International Journal of Obesity, leveraged the UK Biobank—one of the world's richest prospective biomedical databases—to examine whether newly proposed definitions of "clinical obesity" predict autoimmune disease incidence over the long term.

The concept of "clinical obesity" moves beyond simple BMI thresholds, incorporating functional impairment, metabolic dysregulation, and organ-specific consequences of excess adiposity. This more nuanced classification is gaining traction in clinical guidelines, and Xu et al.'s study is among the first to test its epidemiological validity in relation to autoimmune outcomes. Their findings indicate that individuals meeting clinical obesity criteria face a significantly elevated risk of developing a range of autoimmune conditions compared to those with BMI-defined obesity alone. This suggests that the functional severity of obesity, not merely excess weight, is what drives immune risk—a finding with important implications for risk stratification and intervention timing.

The long-term prospective design of the UK Biobank study minimizes recall bias and reverse causality concerns that can undermine cross-sectional or retrospective studies. The breadth of autoimmune outcomes examined also strengthens confidence that this is a broad immunological phenomenon rather than a disease-specific signal.

Key Takeaway — Xu et al. (2025): Clinically defined obesity—beyond BMI alone—is a robust long-term predictor of autoimmune disease incidence in a large prospective UK cohort, underscoring the value of functional obesity assessment in clinical practice.

Real-World Evidence: Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Analysis

Complementing the UK Biobank data, Lin et al. (2026) applied rigorous epidemiological methodology to electronic health records in a real-world Taiwanese clinical population, publishing their results in Scientific Reports. Using propensity score matching—a statistical approach that creates comparable groups of obese and non-obese individuals by balancing confounding variables—their study evaluated the risk of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) across a broad diagnostic spectrum.

Propensity score matching is a critical methodological advantage: it approximates the conditions of a randomized controlled trial using observational data, substantially reducing the risk that observed associations simply reflect underlying differences in demographics, comorbidities, or healthcare utilization between groups. The study confirmed a statistically significant and clinically meaningful elevation in IMID risk among individuals with obesity, with the association holding across multiple disease categories.

Importantly, the use of real-world electronic health records provides ecological validity—these are not carefully selected research participants but everyday patients receiving routine care. This bolsters the generalizability of findings to clinical populations globally, including diverse ethnic groups underrepresented in some European biobank studies.

Key Takeaway — Lin et al. (2026): In a real-world, propensity score-matched cohort using electronic health records, obesity independently and significantly increases the risk of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, with findings applicable to diverse clinical populations.

Large-Scale Cross-Disease Analysis: Breadth of the Inflammatory Burden

Mousavi et al. (2025), publishing in Frontiers in Endocrinology, took a distinctively broad epidemiological lens, conducting a large-scale analysis to assess obesity as a risk factor across the full spectrum of chronic, non-communicable inflammatory diseases. This study moved beyond a single disease category to map the comprehensive inflammatory disease burden attributable to obesity.

Their analysis highlighted that the relationship between obesity and inflammatory disease is not confined to classically "metabolic" conditions. Skin diseases (such as bullous pemphigoid and psoriasis), connective tissue diseases, and vasculitides all showed elevated risk in individuals with obesity. The multicenter, multi-country scope of the analysis—incorporating data from Germany and other European centers with internationally recognized expertise in autoimmune diseases—adds considerable credibility. The authorship includes leading researchers from institutions with specialty programs in autoimmune blistering diseases, scleroderma, and vasculitis, ensuring domain expertise in disease classification and outcome ascertainment.

The breadth of the findings is both striking and clinically important: it implies that any clinician caring for a patient with obesity should be attentive to immune-mediated disease across virtually every organ system, not just metabolic and cardiovascular complications.

Key Takeaway — Mousavi et al. (2025): Obesity is a consistent, large-scale risk factor not just for metabolic diseases but for a wide array of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases spanning multiple organ systems, from skin to connective tissue to vasculature.

The Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Quantifying the Risk

For the highest level of evidence synthesis, Spatocco et al. (2026), publishing in Obesity (Silver Spring), conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis specifically examining obesity as a risk factor for autoimmune diseases. This study pooled quantitative data from multiple primary studies, enabling the derivation of summary effect estimates—the most statistically powerful form of evidence available in observational epidemiology.

Meta-analyses are valuable precisely because they synthesize heterogeneous studies into a unified estimate, accounting for variation across populations, methodologies, and disease definitions. Spatocco et al.'s findings confirmed a statistically significant increase in autoimmune disease risk among individuals with obesity, with pooled effect sizes suggesting a meaningful—and not trivial—elevation in risk across multiple autoimmune conditions. The systematic methodology, including predefined inclusion criteria, quality assessment of primary studies, and assessment of publication bias, lends this analysis the rigor required to inform clinical and public health guidelines.

This study is particularly valuable for translating the field's evidence into a single, actionable number that clinicians and guideline bodies can reference when communicating risk to patients or designing prevention protocols.

Key Takeaway — Spatocco et al. (2026): A systematic review and meta-analysis confirms a statistically significant, pooled elevation in autoimmune disease risk attributable to obesity, providing the strongest quantitative synthesis of the evidence to date.

Comorbidities, Mechanisms, and Treatment Horizons

Wang et al. (2025), writing in Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, provided a comprehensive overview of obesity's comorbidities alongside emerging biological mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. While their review spans the full comorbidity landscape, the immune dimension receives substantial attention—situating autoimmune and inflammatory disease risk within the broader ecosystem of obesity-related pathology.

The authors emphasize that inflammation is the common biological thread linking obesity's diverse complications: it connects insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes to cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, certain cancers, and now, increasingly recognized, autoimmune diseases. This integrative framing is therapeutically consequential. Interventions that target adipose inflammation—whether through lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy (including emerging GLP-1 receptor agonists with pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects), or bariatric surgery—may simultaneously reduce risk across multiple comorbidity domains, including immune-mediated disease.

Wang et al. also highlight future challenges: the heterogeneity of obesity phenotypes means that population-level risk estimates may obscure important variation. Not all individuals with a given BMI face equal immune risk, and precision medicine approaches that better characterize immunological phenotype alongside adiposity metrics may be needed to optimize individual-level prevention and treatment.

Key Takeaway — Wang et al. (2025): Inflammation is the shared mechanistic thread connecting obesity to its full comorbidity spectrum, and emerging therapies targeting adipose inflammation—including GLP-1 receptor agonists and bariatric surgery—offer promising multi-disease risk reduction, including for autoimmune conditions.

What This Means for Clinical Practice and Public Health

1. We Are Framing Obesity Too Narrowly

For decades, obesity has been defined through a metabolic lens—hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk. While this framing is accurate, it is incomplete. Emerging evidence now positions obesity as a condition of chronic immune activation and systemic inflammatory remodeling. Adipose tissue is not inert storage; it is an active endocrine and immune organ capable of reshaping immune tolerance and inflammatory tone across multiple organ systems.

2. Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation Is Not Benign

The persistent elevation of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and leptin in obesity creates a biological environment that lowers the threshold for autoimmunity. Regulatory T-cell suppression, macrophage polarization toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes, and gut barrier disruption are not theoretical constructs—they are measurable immunologic shifts. When sustained over years, this inflammatory burden becomes a fertile substrate for autoimmune disease development.

3. Epidemiology Now Matches Mechanism

Large-scale cohort studies, real-world electronic health record analyses, and systematic meta-analyses converge on a consistent conclusion: obesity significantly elevates the risk of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. The signal is broad, reproducible, and biologically plausible. This is no longer associative noise—it is a coherent pattern.

4. Clinical Practice Must Adapt

Obesity should be treated as an immunological risk state, not merely a cardiometabolic comorbidity. Risk stratification in patients with obesity should include awareness of autoimmune vulnerability. Conversely, patients presenting with new-onset autoimmune disease should undergo careful assessment of adiposity and metabolic health. Interdisciplinary collaboration between endocrinology, rheumatology, gastroenterology, dermatology, and obesity medicine is now clinically justified.

5. Weight Loss Is an Immunologic Intervention

Lifestyle intervention, pharmacotherapy—including GLP-1 receptor agonists—and bariatric surgery do more than reduce body weight. They reduce systemic inflammation, modulate cytokine profiles, and partially restore immune balance. Framing weight reduction as an immune-modifying strategy may transform patient motivation and therapeutic prioritization.

6. Public Health Implications Are Profound

If obesity fuels autoimmune disease incidence, then rising global obesity prevalence predicts escalating inflammatory disease burden. Prevention strategies—food policy reform, physical activity infrastructure, early-life intervention—must be viewed not only as metabolic investments but as immune health strategies.

7. The Time for Conceptual Expansion Is Now

Medicine evolves when paradigms shift. The accumulating evidence demands that we expand our understanding of obesity—from a metabolic condition to a systemic, immune-modifying disorder. The implications for prevention, screening, and therapeutic innovation are too significant to ignore.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Does obesity directly cause autoimmune disease, or is the relationship merely associational?

The evidence increasingly supports a causal relationship, though definitive proof from randomized controlled trials is inherently difficult to obtain for long-term disease outcomes. Mechanistic studies (Jiang et al., 2025) show that obesity-induced immune dysregulation—through cytokine imbalance, adipokine signaling, gut dysbiosis, and Treg depletion—directly disrupts the immune pathways that maintain self-tolerance. Propensity score-matched cohort designs (Lin et al., 2026) and prospective longitudinal data (Xu et al., 2025) substantially reduce confounding, and meta-analytic pooling (Spatocco et al., 2026) confirms consistent risk elevation across heterogeneous populations. The biological plausibility combined with epidemiological consistency across multiple study designs strongly supports causality.

2. Which autoimmune or inflammatory diseases are most strongly associated with obesity?

Across the reviewed studies, elevated risk was observed for a broad range of conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis), systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, bullous pemphigoid, and various vasculitides. Mousavi et al. (2025) demonstrated that this risk extends across virtually the entire spectrum of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, suggesting a systemic rather than disease-specific effect.

3. Is BMI a sufficient measure of obesity-related immune risk?

Xu et al. (2025) found that "clinical obesity"—a more nuanced classification incorporating functional impairment and metabolic markers—predicted autoimmune disease risk more robustly than BMI alone. This suggests that not all individuals with an elevated BMI carry equal immunological risk, and that assessment of adiposity-related functional and metabolic severity adds important prognostic information. Future clinical guidelines may need to incorporate these multidimensional obesity assessments.

4. Can weight loss reverse obesity-related immune dysfunction?

Evidence suggests yes, at least partially. Reductions in adipose tissue mass—particularly visceral fat—are associated with decreased circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, improved Treg function, and restoration of more balanced immune responses. Wang et al. (2025) note that bariatric surgery and GLP-1 receptor agonists show particular promise in reducing systemic inflammation. Some patients with obesity-associated autoimmune disease have shown clinical improvement following significant weight loss, though this varies by disease type, chronicity, and individual factors.

5. Do children and adolescents with obesity face similar autoimmune risks?

While the studies reviewed focused on adult populations, the mechanistic pathways described by Jiang et al. (2025) are not age-specific. Childhood obesity induces similar adipose tissue inflammation, cytokine dysregulation, and gut microbiome disruption. Epidemiological data in pediatric populations are less mature, but early-life obesity is increasingly associated with the development of autoimmune conditions in adolescence and young adulthood. Pediatric obesity prevention may therefore carry immune health benefits extending well beyond metabolic outcomes.

6. How does the gut microbiome connect obesity and autoimmune disease?

The gut microbiome plays a central regulatory role in immune education and tolerance. Obesity-associated gut dysbiosis—characterized by reduced microbial diversity and shifts toward pro-inflammatory bacterial taxa—disrupts intestinal barrier integrity and promotes translocation of bacterial products into systemic circulation, a phenomenon that chronically stimulates immune activation. Jiang et al. (2025) emphasize this gut-immune axis as a critical mechanistic link. Interventions targeting gut microbiome composition (through dietary change, prebiotics, probiotics, or fecal microbiota transplantation) represent an emerging therapeutic frontier.

7. Should patients with existing autoimmune disease be specifically counseled about weight management?

Yes, and urgently so. Not only does obesity increase the risk of developing autoimmune diseases, it also worsens outcomes in patients with established disease. Systemic inflammation driven by adipose tissue can reduce treatment responsiveness, promote disease flares, and compound organ damage. Rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, and other specialists managing autoimmune conditions should integrate obesity assessment and management into routine care plans, ideally in collaboration with obesity medicine specialists. Weight loss should be considered a therapeutic adjunct, not an afterthought.

Clinical Risk Assessment Flowchart

Evaluating autoimmune vulnerability in patients with obesity based on the 2025 AACE consensus algorithm and the risk stratification models from the Xu et al. (2025) and Spatocco et al. (2026) studies

Step 1: Baseline Adiposity & Metabolic Phenotyping

Calculate BMI & Waist Circumference: Identify if the patient meets "Clinical Obesity" criteria. A BMI ≥30 kg/m² accompanied by elevated visceral adiposity

Assess Metabolic Health: Evaluate for the "Metabolically Unhealthy Obesity" (MUO) phenotype:

Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).

Dyslipidemia (Elevated triglycerides, low HDL).

Hypertension.

Identify "Inflammatory Hotspots": Check for the presence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD/MASLD), which acts as a secondary site of systemic cytokine spillover.

Step 2: Systemic Inflammatory Screening (The "Silent" Phase)

Order High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP): Use this as a proxy for the systemic inflammatory load generated by adipose tissue.

Evaluate Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR): Monitor for persistent elevations that cannot be explained by acute infection.

Check Vitamin D Levels: Low 25(OH)D is common in obesity due to sequestration and is a known co-factor in the loss of immune tolerance.

Step 3: Targeted Autoimmune Symptom Review

Dermatological Scan: Look for plaque psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, or unexplained blistering (potential Bullous Pemphigoid).

Musculoskeletal Assessment: Screen for morning stiffness >30 minutes, joint swelling, or chronic enthesitis (inflammation where tendons meet bone).

Gastrointestinal History: Inquire about persistent change in bowel habits, hematochezia, or nocturnal diarrhoea (screening for IBD).

Step 4: Stratification of "Lowered Threshold" Risk

Family History: Document first-degree relatives with autoimmune conditions.

Leptin Check (Optional/Clinical Trial): In research settings, evaluate for hyperleptinemia, which significantly suppresses Treg (regulatory) cell function.

Genetic Context: If available, note HLA-DRB1 or other high-risk alleles that, when combined with obesity, create a "perfect storm" for disease onse

Step 5: Intervention & "Immune Cooling"

Initiate Metabolic Stewardship: Use GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors for their pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects.

Gut Microbiome Modulation: Prescribe a high-fibre, Mediterranean-style diet to repair the "Leaky Gut" and reduce metabolic endotoxemia

Physical Activity: Emphasize resistance training to improve myokine production (e.g., IL-6 from muscle can actually have anti-inflammatory counter-effects on adipose tissue).

Step 6: Longitudinal Monitoring

Bi-Annual Re-evaluation: If hs-CRP remains elevated despite weight loss, consider referral to a Rheumatologist or Immunologist for subclinical screening (e.g., ANA, RF, or CCP titers).

Monitor "Immune Remission": Track the reduction of inflammatory markers alongside fat mass loss to validate the "Weight Loss as Immunotherapy" approach.

Author’s Note

The intersection between obesity and immune-mediated disease represents one of the most important—and underrecognized—shifts in modern medicine. For decades, obesity was framed primarily as a disorder of glucose metabolism and cardiovascular risk. However, emerging evidence from mechanistic immunology, large-scale biobank analyses, real-world cohort studies, and meta-analyses now compels us to reconsider that narrative.

As a physician trained in internal medicine and committed to evidence-based scholarship, my goal in writing this article was to synthesize the most rigorous 2025–2026 research into a clinically meaningful framework. The studies discussed herein were selected not for sensational appeal, but for methodological strength—prospective design, propensity score matching, systematic review standards, and mechanistic plausibility.

Obesity is not merely excess weight; it is a state of chronic, systemic immune activation. Understanding this reframes weight management from an aesthetic or lifestyle issue into a genuine immunological and preventive health priority.

This article is intended for clinicians, researchers, and informed readers who seek a deeper scientific understanding of how metabolic and immune systems intersect. It is not meant to induce alarm, but rather to encourage earlier intervention, more comprehensive risk assessment, and interdisciplinary collaboration in managing patients with obesity and inflammatory disease.

As the science continues to evolve, so too must our clinical mindset. The evidence is increasingly clear: metabolic health and immune health are inseparable.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual circumstances vary, and treatment decisions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Related Articles

Managing Diabesity: A Complete Guide to Weight Loss and Blood Sugar Control | DR T S DIDWAL

The BMI Paradox: Why "Normal Weight" People Still Get High Blood Pressure | DR T S DIDWAL

Breakthrough Research: Leptin Reduction is Required for Sustained Weight Loss | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Jiang, Z., Tabuchi, C., Gayer, S. G., & Bapat, S. P. (2025). Immune dysregulation in obesity. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, 20(1), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-051222-015350

Lin, Y.-J., Hsu, W.-H., Lai, C.-C., et al. (2026). Obesity and risk of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A real-world propensity score-matched cohort study using electronic health records. Scientific Reports, 16, 5332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36400-w

Mousavi, S. M., Bieber, K. B., Zirpel, H., Vorobyev, A., Olbrich, H., Papara, C., De Luca, D. A., Thaci, D., Schmidt, E., Riemekasten, G., Lamprecht, P., Laudes, M., Kridin, K., & Ludwig, R. J. (2025). Large-scale analysis highlights obesity as a risk factor for chronic, non-communicable inflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 16, 1516433. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1516433

Spatocco, I., Mele, G., De Rosa, G., Fusco, C., Ruggiero, K., Pellegrini, V., Carreras, F., La Grotta, R., Ceriello, A., Procaccini, C., Matarese, G., Prattichizzo, F., & de Candia, P. (2026). Obesity as a risk factor for autoimmune diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity, 34(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.70044

Wang, L., Wang, Q., Xiong, Y., Shi, W., & Qi, X. (2025). Obesity and its comorbidities: Current treatment options, emerging biological mechanisms, future perspectives and challenges. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 18, 3427–3445. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S540103

Xu, M., Li, M., Zhang, Y., et al. (2025). Long-term impact of newly-proposed clinical obesity on autoimmune disease incidence: Insights from the UK Biobank. International Journal of Obesity. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-025-01970-8