How Sarcopenia Is Diagnosed: Tests, Criteria, and Early Warning Signs Explained

Diagnose sarcopenia using strength, muscle mass, and performance tests such as grip dynamometry, DXA, and gait speed. Learn early warning signs, diagnostic criteria, and how early detection can help reverse age-related muscle loss

SARCOPENIA

11/6/20258 min read

How Is Sarcopenia Diagnosed?

Have you ever felt weaker climbing stairs, noticed your grip strength fading, or found daily activities a bit harder than before? These subtle signs could be more than just “getting older.” They might be early indicators of sarcopenia—the age-related loss of muscle mass, strength, and function that silently affects millions worldwide.

The good news? Detecting it early can help prevent frailty, falls, and loss of independence—and even reverse much of the muscle decline with the right interventions.

Clinical Pearls

1. Strength loss often precedes muscle loss.

Research shows that a decline in muscle strength (dynapenia) typically occurs before a measurable loss in muscle mass. Hence, a simple grip strength test can identify sarcopenia early—before major physical decline sets in.

2. Questionnaires like SARC-F are valuable but not diagnostic alone.

Tools such as SARC-F or SARC-CalF provide quick screening for risk, but diagnosis requires objective strength, mass, and performance assessments for confirmation.

3. The DXA scan remains the gold standard for measuring muscle mass.

Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) offers a precise and reproducible assessment of muscle quantity, though newer tools like ultrasound and D3-creatine dilution are emerging as convenient and accurate alternatives.

4. Population-specific cutoff values matter.

Ethnic and regional variations affect baseline muscle mass, so diagnostic cutoffs differ between populations. For example, Asian adults, especially women, often have lower absolute muscle mass despite similar strength levels.

5. Sarcopenia is a diagnosable and billable condition.

With the ICD-10-CM code M62.84, sarcopenia is now officially recognized as a distinct disease entity—encouraging earlier detection, insurance coverage, and appropriate clinical management.

Why Proper Diagnosis Is Crucial

Sarcopenia is associated with a lower quality of life, an increased risk of falls and fractures, and a 29% to 51% higher mortality risk [Dent et al., 2021]. Early detection allows for interventions—like exercise and nutritional support—to preserve muscle function, maintain independence, and improve overall health outcomes [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019]..Projections show its worldwide prevalence is expected to soar from 50 million individuals in 2010 to roughly 200 million by 2050 [Fielding et al., 2011].

The Two Main Diagnostic Approaches

Medical professionals utilise standardised criteria and population-specific data for diagnosis:

International Consensus Guidelines: These are standardized criteria developed by expert bodies, including:

EWGSOP2 (European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People) [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019]

AWGS (Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia) [Chen et al., 2014]

FNIH (Foundation for the National Institutes of Health) [Studenski et al., 2014]

The Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS), which introduced a globally endorsed definition in 2024, incorporates muscle mass, strength, and physical performance [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

Population-Specific Cutoff Points: These criteria are tailored to specific groups based on ethnicity, geography, and demographics, often calculated using the standard deviation from the mean of a younger reference population [Boshnjaku & Krasniqi, 2024]. This is vital since studies show distinct patterns of muscle mass decline in Asian adults, challenging the universal application of global criteria [Chen et al., 2014].

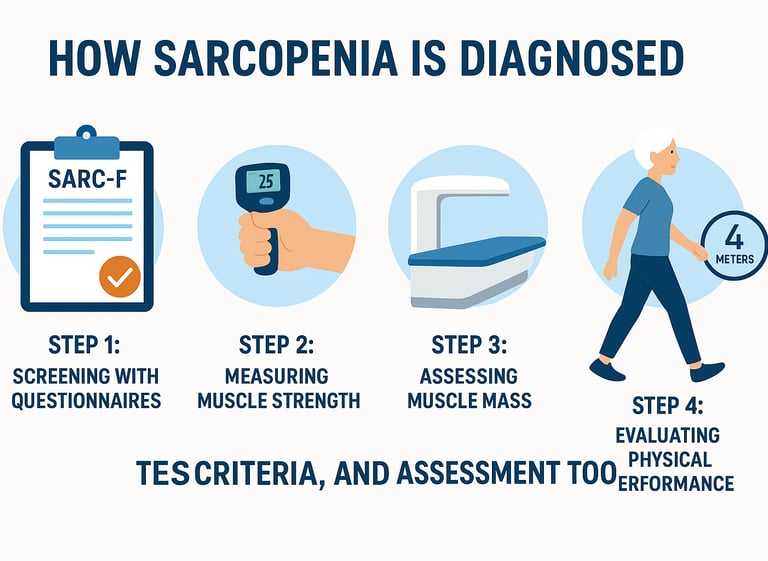

Step-by-Step: Diagnosing Sarcopenia (EWGSOP2 Pathway)

The diagnostic process typically follows a structured pathway:

Step 1: Screening with Questionnaires

The initial step is a simple questionnaire to identify potential cases:

SARC-F Questionnaire: This five-item tool assesses strength, assistance for walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and falls. A score of 4 or higher suggests probable sarcopenia [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

SARC-CalF: An enhanced version that includes a calf circumference measurement, offering higher sensitivity and accuracy [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

Step 2: Measuring Muscle Strength

If screening is positive, muscle strength is assessed:

Grip Strength Test: You squeeze a dynamometer. Low grip strength indicates probable sarcopenia. Typical cutoffs are less than 27 kg for men and less than 16 kg for women, though values may vary [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

Chair Stand Test: Measures lower body strength. Standing up from a chair five times in longer than 15 seconds suggests muscle weakness [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

Step 3: Assessing Muscle Mass

If muscle weakness is confirmed, muscle mass is measured:

DXA Scan (Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry): Considered the gold standard, this quick, low-radiation scan measures appendicular skeletal muscle mass (arms and legs) [Dent et al., 2021].

BIA (Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis): A non-invasive, portable, and less expensive technique that estimates body composition, though hydration status can influence results [Dent et al., 2021].

Ultrasound: Offers portability and real-time imaging without radiation, assessing both muscle quantity and quality [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

CT or MRI Scans: Provide the most detailed images, but are usually reserved for research or complex cases [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

D3-Creatine Dilution Method: An emerging, promising technique for accurate muscle mass evaluation [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

Step 4: Evaluating Physical Performance (Severity Assessment)

The final step assesses the impact on daily function:

Gait Speed Test: Walking speed is measured over a short distance (usually 4 meters). A speed slower than 0.8 meters per second indicates severe sarcopenia [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): A validated assessment combining balance, gait speed, and chair stands to provide a comprehensive functional score [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

Who Should Be Tested?

Consider discussing sarcopenia screening with your doctor if you:

Are 60 years or older

Have experienced unintentional weight loss

Feel weaker than you used to

Have difficulty climbing stairs or getting up from a chair

Have fallen multiple times

Have chronic conditions like heart disease, kidney disease, or diabetes

Are less physically active than before

The Importance of Early Detection

Projections indicate a substantial increase in sarcopenia's worldwide prevalence, expected to rise from 50 million individuals in 2010 to approximately 200 million by 2050. This makes early detection increasingly crucial.

What Do the Results Mean?

Based on the tests, the diagnosis is categorised:

No Sarcopenia: Normal muscle mass, strength, and function.

Probable Sarcopenia: Low muscle strength.

Confirmed Sarcopenia: Low muscle strength AND low muscle mass.

Severe Sarcopenia: Low muscle strength, low muscle mass, AND poor physical performance [Cruz-Jentoft et al., 2019].

Interventions After Diagnosis

If diagnosed, evidence-based interventions can significantly improve outcomes:

Exercise Interventions: Resistance training and progressive strength exercises are highly effective for building and maintaining muscle [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

Nutritional Support: A recommended daily protein intake of at least 1.2 g/kg is a cornerstone of management [Voulgaridou et al., 2024].

Medical Management: Optimizing underlying chronic conditions (like heart disease or diabetes) and discussing emerging treatment options [Fielding et al., 2011].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How do I know if I should get tested for sarcopenia?

If you’re over 60 years old, notice a weaker grip, slower walking, or trouble rising from a chair, or have had unintentional weight loss or repeated falls, you should discuss screening with your doctor.

2. What is the first step in diagnosis?

Your doctor will likely start with a SARC-F or SARC-CalF questionnaire, followed by grip strength or chair stand tests. If these suggest weakness, further evaluation of muscle mass and performance follows.

3. Are the tests painful or invasive?

No. All standard tests—grip dynamometry, DXA, BIA, gait speed, or ultrasound—are painless, non-invasive, and can often be done within one or two clinic visits.

4. Can I have sarcopenia even if I’m not elderly?

Yes. Sarcopenia can start in your 40s or 50s, particularly in those who are sedentary, have chronic diseases (like diabetes or kidney disease), or experience hormonal and nutritional deficiencies.

5. What does a “confirmed sarcopenia” diagnosis mean?

It means both low muscle strength and low muscle mass are present. If your physical performance (like gait speed) is also impaired, it’s classified as severe sarcopenia.

6. How accurate are these diagnostic methods?

When combined—screening questionnaires, grip strength, and DXA/BIA—diagnostic accuracy is excellent. The Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS) and EWGSOP2 guidelines ensure consistent, validated results.

7. Can sarcopenia be reversed once diagnosed?

Yes—resistance training, adequate protein intake (≥1.2 g/kg/day), and targeted medical management can restore muscle function and strength, even in older adults.

Key Takeaway

Sarcopenia isn't just an inevitable part of getting older—it's a diagnosable and treatable medical condition.

If you or your doctor notice signs like muscle weakness or slower walking, simple, painless tests (like checking your grip strength or walking speed) can confirm the diagnosis. The good news is that once sarcopenia is detected, the condition can often be managed and even reversed!

By focusing on two key interventions—resistance exercises (like lifting weights) and ensuring enough protein in your diet—you can actively rebuild muscle, maintain your strength, and protect your independence for years to come. Don't ignore the signs; talk to your doctor today!

Sarcopenia isn’t just an inevitable part of aging—it’s a diagnosable, treatable condition. With simple tests, early recognition, and scientifically backed interventions, muscle decline can be slowed or even reversed.

If you notice weakness, slower walking, or fatigue, don’t ignore it—talk to your healthcare provider about screening for sarcopenia today.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with your healthcare provider for personalized medical guidance.

Related Articles

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Who Gets Sarcopenia? Key Risk Factors & High-Risk Groups Explained | DR T S DIDWAL

How to Prevent Sarcopenia: Evidence-Based Strategies That Work | DR T S DIDWAL

Citations

Dent, E., Woo, J., Scott, D., & Hoogendijk, E. O. (2021). Sarcopenia measurement in research and clinical practice. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 90, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.003

Voulgaridou, G., Tyrovolas, S., Detopoulou, P., Tsoumana, D., Drakaki, M., Apostolou, T., Chatziprodromidou, I. P., Papandreou, D., Giaginis, C., & Papadopoulou, S. K. (2024). Diagnostic Criteria and Measurement Techniques of Sarcopenia: A Critical Evaluation of the Up-to-Date Evidence. Nutrients, 16(3), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030436

Boshnjaku, A., & Krasniqi, E. (2024). Diagnosing sarcopenia in clinical practice: international guidelines vs. population-specific cutoff criteria. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1405438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1405438

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Bahat, G., Bauer, J., Boirie, Y., Bruyère, O., Cederholm, T., Cooper, C., Landi, F., Rolland, Y., Sayer, A. A., Schneider, S. M., Sieber, C. C., Topinkova, E., Vandewoude, M., Visser, M., Zamboni, M., & Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2 (2019). Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and ageing, 48(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

Fielding, R. A., Vellas, B., Evans, W. J., Bhasin, S., Morley, J. E., Newman, A. B., Abellan van Kan, G., Andrieu, S., Bauer, J., Breuille, D., Cederholm, T., Chandler, J., De Meynard, C., Donini, L., Harris, T., Kannt, A., Keime Guibert, F., Onder, G., Papanicolaou, D., Rolland, Y., … Zamboni, M. (2011). Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 12(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003

Chen, L. K., Liu, L. K., Woo, J., Assantachai, P., Auyeung, T. W., Bahyah, K. S., Chou, M. Y., Chen, L. Y., Hsu, P. S., Krairit, O., Lee, J. S., Lee, W. J., Lee, Y., Liang, C. K., Limpawattana, P., Lin, C. S., Peng, L. N., Satake, S., Suzuki, T., Won, C. W., … Arai, H. (2014). Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025

Studenski, S. A., Peters, K. W., Alley, D. E., Cawthon, P. M., McLean, R. R., Harris, T. B., Ferrucci, L., Guralnik, J. M., Fragala, M. S., Kenny, A. M., Kiel, D. P., Kritchevsky, S. B., Shardell, M. D., Dam, T. T., & Vassileva, M. T. (2014). The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 69(5), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu010

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Baeyens, J. P., Bauer, J. M., Boirie, Y., Cederholm, T., Landi, F., Martin, F. C., Michel, J. P., Rolland, Y., Schneider, S. M., Topinková, E., Vandewoude, M., Zamboni, M., & European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (2010). Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age and ageing, 39(4), 412–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq034