Sarcopenia vs. Osteoporosis: Key Differences for Bone & Muscle Health

Don't let aging steal your strength. Get the facts on preventing sarcopenia and osteoporosis with optimal nutrition, resistance training, and early diagnosis (DXA, SARC-F).

SARCOPENIA

DR T S DIDWAL MD

11/3/20259 min read

Sarcopenia vs. Osteoporosis: Understanding the Key Differences for Better Health

As our global population ages, two silent conditions are emerging as major health concerns: sarcopenia and osteoporosis. While both affect older adults and can significantly impact quality of life, they target different body systems and require distinct approaches to prevention and treatment. Understanding the key differences between these conditions is essential for maintaining health and independence in later years.

Clinical Pearls

Muscle and Bone Are Biologically Interconnected:

Muscle contractions provide mechanical loading that stimulates bone formation. Sarcopenia indirectly worsens osteoporosis by reducing bone stress signals—highlighting the need for combined muscle-bone interventions.Hormonal Crosstalk Drives Both Conditions:

Declining levels of estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, and IGF-1 contribute simultaneously to bone resorption and muscle atrophy, explaining why both disorders often emerge post-menopause or after age 60.Inflammation Accelerates Degeneration:

Elevated cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α disrupt both osteoblast and myocyte function, linking chronic low-grade inflammation (“inflammaging”) to the progression of both sarcopenia and osteoporosis.DXA Can Assess Both Bone and Muscle:

While primarily used for bone mineral density (BMD), modern DXA technology can also quantify appendicular lean mass—offering a single, dual-purpose diagnostic tool for both conditions.Resistance Training Is the Most Potent Dual Therapy:

Progressive resistance exercise not only reverses muscle loss but also enhances bone density by increasing mechanical load and anabolic hormone activity—making it the cornerstone of prevention and rehabilitation.

What Is Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by reduced bone density and deterioration of bone tissue, making bones fragile and susceptible to fractures. Often called the "silent disease," osteoporosis progresses without symptoms until a fracture occurs—typically in the hip, spine, or wrist.

Key Facts About Osteoporosis:

Definition: Bone mineral density (BMD) more than 2.5 standard deviations below the young adult mean

Global Impact: Over 200 million people worldwide are affected

Primary Risk: Fractures that can lead to disability, loss of independence, and increased mortality

Most Affected: Postmenopausal women and elderly populations

How Osteoporosis Develops

Bone is living tissue that continuously remodels through a balanced process of formation (by osteoblasts) and breakdown (by osteoclasts). Osteoporosis occurs when bone resorption outpaces bone formation, resulting in porous, weakened bones.

The most common form, postmenopausal osteoporosis, develops when declining estrogen levels after menopause accelerate bone loss. Other causes include chronic diseases, certain medications (especially corticosteroids), hormonal disorders, and nutritional deficiencies.

What Is Sarcopenia?

Sarcopenia refers to the progressive, age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function. Coined in 1989, this condition affects physical performance, increases fall risk, and reduces functional independence.

Key Facts About Sarcopenia:

Prevalence: Affects 5-13% of people in their 70s and 11-50% by age 80

Future Impact: Expected to affect over 500 million older adults by 2050

Diagnosis Criteria: Requires low muscle strength, low muscle quantity/quality, and/or low physical performance

Severity Levels: Ranges from probable to confirmed to severe sarcopenia

How Sarcopenia Develops

Sarcopenia results from an imbalance between muscle protein synthesis and breakdown. Multiple factors contribute to this process, including chronic inflammation, hormonal changes (reduced testosterone and growth hormone), mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and altered neuromuscular signaling.

As we age, increased inflammatory cytokines and decreased anabolic hormones disrupt muscle homeostasis, leading to progressive muscle tissue loss.

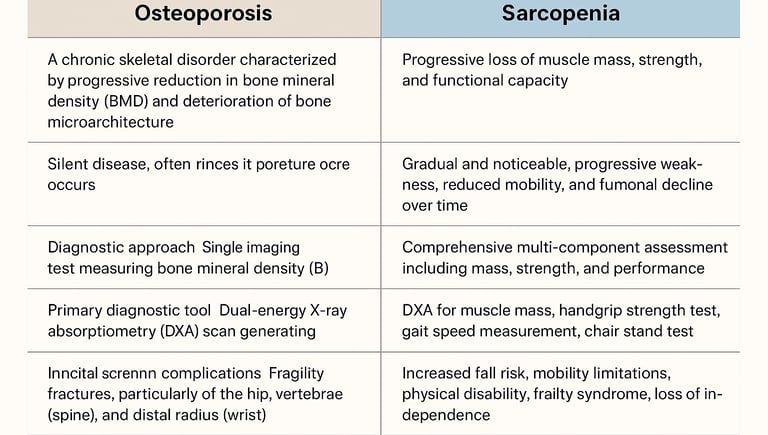

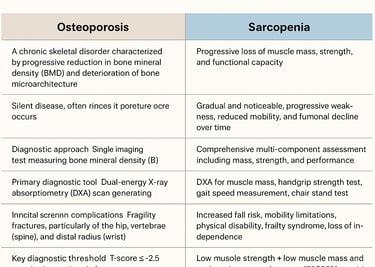

The Critical Differences: Sarcopenia vs. Osteoporosis

While osteoporosis and sarcopenia share several risk factors and often coexist, they are fundamentally different conditions affecting distinct body systems. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Osteoporosis is a chronic skeletal disorder characterized by a progressive reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone microarchitecture. This leads to increased bone fragility and a higher risk of fractures, particularly in the hip, spine, and wrist. Often called the “silent disease,” osteoporosis typically progresses without symptoms and is usually diagnosed only after a fracture occurs. The primary diagnostic approach involves a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan, which measures BMD and generates a T-score. A T-score of –2.5 or lower compared to the young adult mean confirms osteoporosis. Screening can be initiated using the FRAX® tool, which estimates fracture risk based on clinical factors such as age, gender, prior fractures, and steroid use. Osteoporosis is most prevalent among postmenopausal women and older adults, with complications including chronic pain, deformity, loss of independence, and increased mortality after fractures.

Sarcopenia, on the other hand, is a progressive condition affecting the skeletal muscular system, marked by the gradual loss of muscle mass, strength, and functional capacity. Unlike osteoporosis, sarcopenia’s progression is often noticeable, manifesting as weakness, slower walking speed, difficulty climbing stairs, and reduced mobility over time. Diagnosis requires a multi-component assessment evaluating muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance. Key diagnostic tools include DXA for measuring muscle mass, handgrip strength tests, gait speed assessment, and chair stand tests. The SARC-F questionnaire is commonly used for initial screening to identify individuals at risk. According to the EWGSOP2 criteria, sarcopenia is confirmed when both low muscle strength and low muscle mass and/or performance are present. Major complications include increased fall risk, mobility limitations, physical disability, frailty, and loss of independence, emphasizing the importance of early detection and targeted resistance training interventions.

The Dangerous Connection: When Both Conditions Coexist

Osteosarcopenia, the coexistence of osteopenia/osteoporosis and sarcopenia, has emerged as a critical clinical entity with substantially greater adverse effects on skeletal integrity than either condition alone. Despite its clinical significance, this dual diagnosis lacks a universally accepted definition, creating substantial challenges for healthcare practitioners and researchers.

A comprehensive systematic review encompassing over 64,000 individuals revealed that osteosarcopenia affects approximately 18% of older adults globally, with devastating consequences: a 54% increased risk of falls, doubled fracture risk, and 75% higher mortality rates. However, the prevalence and predictive value of osteosarcopenia vary considerably depending on the diagnostic criteria employed—a reflection of the broader heterogeneity plaguing current definitions.

This inconsistency complicates epidemiological data interpretation and hinders clinical translation. Experts emphasize the urgent need for a standardized, consensus-based definition, potentially termed "osteodynapenia," that incorporates both muscle strength assessments and bone mineral density measurements. Without prospective validation as an independent fracture risk factor, osteosarcopenia risks remaining a theoretical construct rather than evolving into a practical clinical tool. Establishing standardized diagnostic criteria is essential to enable early identification, targeted interventions, and improved outcomes for the growing population of older adults facing this dual skeletal threat.

Geographic Variations in Risk:

European populations: 4.37 times higher osteoporosis risk with sarcopenia

Asian populations: 2.66 times higher risk

American populations: 2.32 times higher risk

Gender differences: Males with sarcopenia show 4.74 times higher osteoporosis risk compared to 3.46 times in females

Shared Risk Factors

Both conditions share common underlying mechanisms:

Hormonal Changes: Declining estrogen and testosterone levels affect both bone density and muscle mass

Chronic Inflammation: Inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α contribute to both bone loss and muscle degradation

Physical Inactivity: Sedentary lifestyle reduces mechanical loading on bones and muscle stimulation

Nutritional Deficiencies: Inadequate calcium, vitamin D, and protein intake affects both systems

Aging: The primary non-modifiable risk factor for both conditions

The Vicious Cycle

When osteoporosis and sarcopenia coexist, they create a destructive feedback loop:

Muscle loss reduces mechanical loading on bones, accelerating bone density loss

Weakened bones increase fracture risk

Fractures lead to immobilization and reduced physical activity

Inactivity causes further muscle loss

The cycle continues, compounding functional decline

Diagnosis: How Each Condition Is Identified

Diagnosing Osteoporosis

Primary Method: Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan generates a T-score comparing your BMD to healthy young adults

Assessment Includes:

Medical history review

Physical examination for height loss or spinal curvature

BMD measurement at the hip, spine, or forearm

Laboratory tests (calcium, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone)

FRAX® tool for fracture risk prediction

Diagnosing Sarcopenia

Comprehensive Assessment includes multiple components:

Screening: SARC-F questionnaire to identify at-risk individuals

Muscle Mass Measurement:

DXA for appendicular lean mass

BIA (bioelectrical impedance analysis)

MRI or CT for detailed assessment

Muscle Strength Testing:

Grip strength measurement

Chair stand test

Physical Performance Evaluation:

Gait speed test

Timed up-and-go (TUG) test

6-minute walk test

Short physical performance battery (SPPB)

Treatment and Management: Distinct Yet Complementary Approaches

Managing Osteoporosis

Pharmacological Interventions:

Bisphosphonates (prevent bone breakdown)

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)

Denosumab (reduces bone resorption)

Teriparatide (promotes bone formation)

Lifestyle Modifications:

Weight-bearing exercises (walking, jogging, dancing)

Calcium supplementation (1,000-1,200 mg daily)

Vitamin D supplementation (800-1,000 IU daily)

Smoking cessation

Moderate alcohol consumption

Managing Sarcopenia

Primary Interventions:

Resistance Training: Progressive strength training is the cornerstone of sarcopenia management. Exercises with weights or resistance bands promote muscle protein synthesis and enhance strength.

Nutritional Optimization:

Adequate protein intake (1.0-1.2 g/kg body weight daily)

High-quality protein sources distributed throughout the day

Vitamin D supplementation for muscle function

Multidisciplinary Approach: Collaboration among physicians, physical therapists, and dietitians optimizes treatment outcomes.

Integrated Management Strategy

Since these conditions often coexist, an integrated approach addresses both simultaneously:

Exercise Programs: Combine resistance training (for muscle) with weight-bearing activities (for bone)

Comprehensive Nutrition: Ensure adequate calcium, vitamin D, and protein intake

Fall Prevention: Environmental modifications, balance training, vision assessment, and medication review

Regular Monitoring: Track both bone density and muscle function over time

Prevention: Your Action Plan for Healthy Aging

Start Early, Stay Consistent

The best time to prevent osteoporosis and sarcopenia is before they develop. Here's your comprehensive prevention strategy:

Physical Activity:

Engage in regular weight-bearing exercise (30 minutes, most days)

Include resistance training 2-3 times weekly

Practice balance exercises like tai chi or yoga

Nutrition:

Consume calcium-rich foods (dairy, leafy greens, fortified products)

Ensure adequate vitamin D through sunlight and diet

Eat protein with every meal (lean meats, fish, legumes, dairy)

Maintain a balanced, nutrient-dense diet

Lifestyle Factors:

Avoid smoking

Limit alcohol consumption

Maintain healthy body weight

Get regular health screenings

Fall Prevention:

Remove home hazards (loose rugs, clutter)

Install adequate lighting

Use assistive devices if needed

Have regular vision checks

The Impact on Quality of Life

Both osteoporosis and sarcopenia significantly affect health and well-being, but in different ways:

Osteoporosis Consequences:

Severe pain from fractures

Loss of height and spinal deformity

Disability and functional limitations

Increased dependency on others

Higher risk of subsequent fractures

Increased mortality (especially after hip fractures)

Sarcopenia Consequences:

Difficulty performing daily activities

Reduced mobility and independence

Increased vulnerability to falls

Development of frailty

Higher hospitalization rates

Decreased quality of life

Combined Impact: When both conditions coexist, the effects multiply. The combination creates greater functional limitations, higher fall and fracture risk, and accelerated decline in independence.

Who's at Highest Risk?

Osteoporosis Risk Factors

Non-Modifiable:

Age (especially over 50)

Female gender

Family history

Menopause

Ethnicity (higher in Caucasian and Asian populations)

Modifiable:

Low calcium and vitamin D intake

Sedentary lifestyle

Smoking

Excessive alcohol use

Long-term corticosteroid use

Low body weight

Sarcopenia Risk Factors

Primary Risk Factors:

Advanced age (especially over 60)

Physical inactivity

Inadequate protein intake

Chronic diseases (diabetes, cardiovascular disease)

Certain medications (glucocorticoids)

Hormonal imbalances

Population Variations: Community-dwelling individuals show higher susceptibility to combined osteoporosis-sarcopenia (3.70 times higher risk) compared to inpatient and outpatient populations.

Future Directions: Hope on the Horizon

Research continues to advance our understanding and treatment of both conditions:

Diagnostic Innovations:

High-resolution imaging for detailed bone microarchitecture assessment

Advanced MRI techniques for muscle quality evaluation

Biomarker development for early detection

Emerging Therapies:

Targeted bone-forming and muscle-building agents

Regenerative medicine approaches (stem cell therapy)

Precision interventions based on genetic profiling

Personalized Medicine: Future treatments will be tailored to individual risk profiles, genetic characteristics, and specific needs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can you have both sarcopenia and osteoporosis at the same time?

Yes. Many older adults experience both conditions simultaneously—a condition sometimes referred to as osteosarcopenia. The combination greatly increases fall and fracture risk and requires integrated treatment.

2. What are the early warning signs of sarcopenia?

Early symptoms include loss of muscle strength, slower walking speed, difficulty climbing stairs, or problems rising from a chair. These are subtle but important indicators of declining muscle function.

3. Is osteoporosis painful before a fracture occurs?

No. Osteoporosis is known as a “silent disease” because it causes no pain or symptoms until a bone breaks. Regular bone density screening (DXA scan) after age 50 is crucial for early detection.

4. What type of exercise helps prevent both conditions?

A combination of resistance training (for muscle) and weight-bearing activities like walking, stair climbing, or dancing (for bone) is most effective. Add balance training such as tai chi to reduce fall risk.

5. How much protein and vitamin D do older adults need?

Most experts recommend 1.0–1.2 g of protein per kg of body weight daily and 800–1,000 IU of vitamin D per day to support both muscle and bone health. Blood levels should be monitored by your healthcare provider.

6. Are these conditions reversible?

While complete reversal may not always be possible, both conditions are highly manageable. Regular exercise, optimal nutrition, and medical therapies can significantly restore function and prevent complications.

7. Who should get screened for sarcopenia and osteoporosis?

Adults over 50—especially postmenopausal women, men with low testosterone, or anyone with chronic disease, frailty, or a history of fractures—should discuss screening with their doctor.

Key Takeaways:

Osteoporosis weakens bones; sarcopenia weakens muscles—both increase fall and fracture risk

Having one condition significantly increases your risk for developing the other

Prevention is possible through exercise, proper nutrition, and healthy lifestyle choices

Early detection and intervention are crucial for maintaining independence and quality of life

Integrated care approaches that address both conditions simultaneously yield the best outcomes

Don't wait for symptoms to appear—osteoporosis is silent until fracture occurs, and sarcopenia develops gradually. Talk to your healthcare provider about screening, especially if you're over 50 or have risk factors. With proper assessment, prevention strategies, and treatment when needed, you can maintain strong bones and muscles well into your later years.

Take action today: Schedule a bone density test, assess your protein intake, start resistance training, and ensure you're getting adequate calcium and vitamin D. Your future self will thank you for the investment in musculoskeletal health you make now.

This information is for educational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult with your healthcare provider for personalized recommendations based on your individual health status and risk factors.

Related Articles

Sarcopenia: The Complete Guide to Age-Related Muscle Loss and How to Fight It | DR T S DIDWAL

Citations

Jin, S., Zheng, F., Liu, H., Liu, L., & Yu, J. (2025). The correlation between sarcopenia and osteoporosis in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine, 12, 1603879. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1603879

Cacciatore, S., Prokopidis, K. & Schlögl, M. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia: two sides of the same coin. Eur Geriatr Med 16, 1749–1752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-025-01275-z

Chen, S., Xu, X., Gong, H., Chen, R., Guan, L., Yan, X., Zhou, L., Yang, Y., Wang, J., Zhou, J., Zou, C., & Huang, P. (2024). Global epidemiological features and impact of osteosarcopenia: A comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle, 15(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13392

Das, C., Das, P. P., & Kambhampati, S. B. S. (2023). Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis. Indian journal of orthopaedics, 57(Suppl 1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-023-01022-1

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., Bahat, G., Bauer, J., Boirie, Y., Bruyère, O., Cederholm, T., Cooper, C., Landi, F., Rolland, Y., Sayer, A. A., Schneider, S. M., Sieber, C. C., Topinkova, E., Vandewoude, M., Visser, M., Zamboni, M., & Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2 (2019). Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and ageing, 48(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169