It's Never Too Late: Midlife Exercise Cuts Dementia Risk by Decades

New 2024-2025 longitudinal studies prove physical activity in midlife (50s/60s) or later significantly reduces dementia risk. Learn how MVPA at any dose protects your brain, regardless of frailty.

EXERCISE

Dr. T.S. Didwal, M.D.

11/29/202514 min read

The question that haunts many of us as we age is simple yet profound: What can we actually do to protect our minds? While we've long known that physical activity benefits our hearts and bodies, emerging research is painting an increasingly compelling picture about its role in protecting our brains from dementia. Recent large-scale longitudinal studies have revealed something truly encouraging—moderate-to-vigorous physical activity can substantially reduce the risk of developing dementia across virtually every stage of adulthood, regardless of your current fitness level or health status.

This isn't just another wellness claim. Four groundbreaking studies published between 2024 and 2025 have provided robust evidence that engaging in physical activity throughout your life may be one of the most powerful tools available for dementia prevention and cognitive health. Whether you're 40, 60, or 80, the message is clear: it's never too early and never too late to harness the protective power of movement.

Clinical Pearls for Dementia Prevention

1. The "Any Dose" Neuroprotection Rule

The Science: Groundbreaking research (Wanigatunga et al., 2025) demonstrates that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) provides substantial protection against all-cause dementia, and this benefit is largely dose-independent above a minimal level. Furthermore, this protection holds true regardless of frailty status or current fitness level.

The Pearl: You don't need to be an athlete to secure brain protection. Even modest, consistent amounts of activities like brisk walking or cycling significantly reduce your risk. If you are frail or managing health issues, you still benefit tremendously; your current health status is not a barrier to starting your cognitive defense.

2. Midlife: The Critical Intervention Window

The Science: The Health and Retirement Study (Wei et al., 2024) specifically highlighted that initiating a regular physical activity routine during your midlife years (40s–60s) significantly reduces the subsequent risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in later life.

The Pearl: If you spent your younger years being sedentary, it's not too late. Midlife is a powerful point of intervention. Starting a routine in your 50s effectively alters your cognitive trajectory, proving that the brain's protective mechanisms are highly responsive to late-onset physical activity.

3. Exercise is the Brain's Fertilizer (BDNF)

The Science: Physical activity is a direct stimulus for the production of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF is a neurotrophin that acts like "fertilizer" for the brain, promoting neuroplasticity—the formation of new neural connections—and compensating for age-related damage (Wei et al., 2024).

The Pearl: When you exercise, you are chemically improving your brain's structure and function. BDNF helps your brain maintain its capacity to learn, adapt, and resist damage. This mechanism is one reason why movement provides protection across different types of dementia. [Image illustrating BDNF stimulating new synapses (neural connections)]

4. Protect Your Pipes to Protect Your Mind

The Science: A primary mechanism of dementia risk reduction is the effect of MVPA on the cerebral vasculature. Regular exercise improves cardiovascular health, ensuring better blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). This enhanced blood supply supports neuronal health and metabolic function.

The Pearl: The health of your blood vessels is intrinsically linked to the health of your memory. Exercise strengthens your circulatory system, effectively reducing risk factors for vascular dementia and ensuring your brain cells receive the oxygen and nutrients they need to stay sharp and resistant to damage.

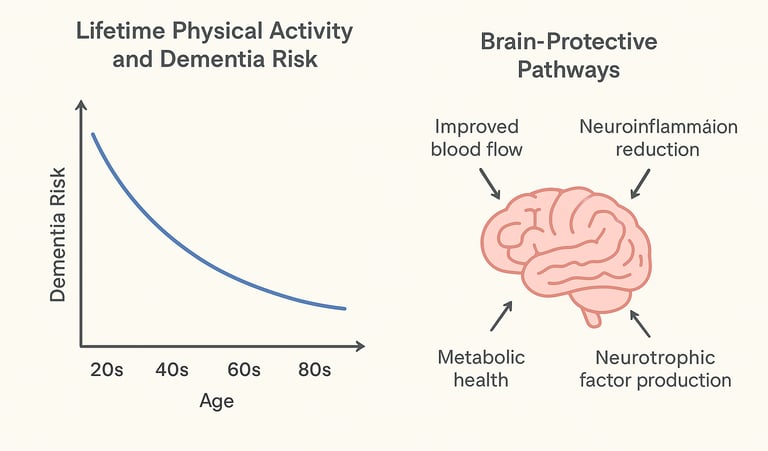

5. Every Active Decade is an Investment

The Science: Analysis of the Framingham Heart Study (Marino et al., 2025) shows that while maintaining activity across the entire adult lifespan provides the greatest cumulative protection, the protective effect of physical activity is independent at different life stages.

The Pearl: Think of physical activity as a compound interest investment for your brain. Every year, every decade you remain active, you add another layer of robust protection against dementia. You gain benefits from the time you start, and these benefits accumulate, making sustained consistency the ultimate goal for lifelong cognitive vitality.

The Four Landmark Studies: A Comprehensive Overview

Study 1: Dose-Independent Dementia Protection Through Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

The first critical finding comes from Wanigatunga and colleagues, whose 2025 study in the Journal of the American Medical Directors Association examined the relationship between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and dementia risk while considering an often-overlooked factor: frailty status (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Key Finding: Even modest amounts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity provide significant protection against all-cause dementia, and remarkably, this benefit holds true regardless of whether someone is frail or not (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Study Details: This research demonstrated that the protective effects of physical activity don't follow a strict dose-response relationship where more is always exponentially better (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). Instead, what matters most is engaging in activity at moderate-to-vigorous intensity levels. This is genuinely encouraging because it means you don't need to become an ultramarathoner to protect your brain. The study's inclusion of frailty status as a variable is particularly important because it addresses a real-world concern: many older adults worry they're "too frail" to benefit from exercise. This research clearly shows that's not the case (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Key Takeaway: You don't need to be in peak physical condition to reduce your dementia risk. Moderate physical activity, performed consistently, offers protective benefits across all fitness levels and health statuses (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Study 2: The Critical Importance of Midlife Physical Activity Habits

Wei and colleagues explored a specific but crucial timeframe in their 2024 Health and Retirement Study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society: what happens when people adopt physical activity habits starting in midlife (Wei et al., 2024).

Key Finding: Physical activity initiated during midlife years significantly reduces the subsequent risk of dementia and cognitive impairment in later life (Wei et al., 2024).

Study Details: This research used longitudinal data to track real-world patterns of physical activity adoption, examining individuals who became active starting around midlife—roughly their 50s and 60s (Wei et al., 2024). The results suggest that midlife physical activity serves as a potential intervention point. You might have spent your 20s and 30s mostly sedentary, but starting a regular exercise routine in your 50s still provides substantial cognitive protection (Wei et al., 2024). This finding challenges the notion that dementia prevention is solely about lifelong habits established in youth. It's genuinely never too late to start (Wei et al., 2024).

Key Takeaway: If you haven't been active throughout your life, beginning physical activity in midlife can still meaningfully reduce your dementia risk (Wei et al., 2024). This timeframe represents a critical intervention window where lifestyle changes still yield significant cognitive benefits.

Study 3: Lifespan Patterns and Dementia Risk in the Framingham Heart Study

Marino and colleagues (2025) contributed to this body of knowledge through an analysis of the Framingham Heart Study, published in JAMA Network Open, focusing on physical activity patterns across the entire adult lifespan (Marino et al., 2025).

Key Finding: Consistent physical activity across different life stages—from early adulthood through older age—shows dose-dependent protective effects against dementia, with the most substantial benefits observed in those maintaining activity across multiple decades (Marino et al., 2025).

Study Details: The Framingham Heart Study is particularly valuable because it has tracked the same individuals for generations, allowing researchers to document long-term physical activity patterns (Marino et al., 2025). Marino's analysis revealed something nuanced: while any physical activity helps, there's a cumulative benefit to maintaining active lifestyles across multiple decades (Marino et al., 2025). Think of it like compound interest for your brain. Someone who was moderately active in their 30s, maintained that activity through their 50s, and continued into their 70s showed greater dementia risk reduction than someone active only in one or two life stages (Marino et al., 2025). However—and this is important—the study also confirmed that starting physical activity at any life stage still provides meaningful protection (Marino et al., 2025).

Key Takeaway: While maintaining lifetime physical activity offers the greatest protection, the protective effects of physical activity are independent and cumulative, meaning you benefit from every active decade regardless of when you start (Marino et al., 2025).

Study 4: Incident Dementia Risk and Lifelong Activity Patterns

Hwang and colleagues' 2024 research, presented through the Alzheimer's & Dementia journal, examined physical activity across the adult life course and its relationship to incident (newly diagnosed) dementia cases in the Framingham Heart Study (Hwang et al., 2024).

Key Finding: Physical activity patterns throughout adulthood—particularly patterns showing consistency or late-life activity initiation—are associated with lower risks of developing dementia (Hwang et al., 2024).

Study Details: By focusing on incident dementia cases (newly diagnosed rather than prevalent cases already present), Hwang's team provides insight into the actual preventive mechanisms of physical activity rather than associations with existing disease (Hwang et al., 2024). The research supports what we're seeing across these studies: multiple patterns of activity confer protection (Hwang et al., 2024). Whether someone was consistently active throughout life or increased their activity in later years, both patterns were associated with lower incident dementia risk (Hwang et al., 2024). This suggests that physical activity works through fundamental neurobiological mechanisms that benefit the brain at any age (Hwang et al., 2024).

Key Takeaway: The protective effects of physical activity against incident dementia are robust across various activity patterns, confirming that cognitive protection is achievable through different pathways of lifetime physical activity engagement (Hwang et al., 2024).

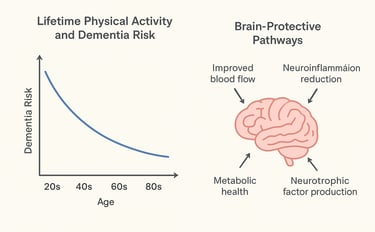

Understanding the Science: Why Physical Activity Protects Your Brain

Before we discuss practical implementation, it's worth understanding the biological mechanisms behind these protective effects. Regular physical activity influences the brain through multiple pathways:

Cardiovascular Health and Cerebral Blood Flow: Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity strengthens your heart and improves vascular function, enhancing blood flow to the brain (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). This means your neurons receive more oxygen and nutrients, supporting cognitive function.

Neuroinflammation Reduction: Chronic neuroinflammation is implicated in dementia pathology. Physical activity reduces systemic and neuroinflammation markers, potentially slowing cognitive decline (Marino et al., 2025).

Neurotropic Factor Production: Exercise stimulates the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein crucial for neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to form new connections and compensate for damage (Wei et al., 2024).

Metabolic Health: Physical activity improves glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes, a known dementia risk factor (Hwang et al., 2024).

Amyloid and Tau Clearance: Some evidence suggests regular physical activity may facilitate the clearance of amyloid and tau proteins, hallmark pathological features of Alzheimer's disease (Marino et al., 2025).

The bottom line: physical activity isn't just good for your muscles and heart—it's fundamentally neuroprotective (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024).

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What counts as "moderate-to-vigorous physical activity"?

Moderate-intensity activities include brisk walking (3-4 miles per hour), recreational cycling, or gardening (Wei et al., 2024). Vigorous-intensity activities include running, competitive sports, or high-intensity interval training (Marino et al., 2025). The key is elevating your heart rate to about 50-70% of maximum (moderate) or 70-85%+ (vigorous) of maximum capacity. According to recent research, consistent engagement in these activities offers significant protection regardless of volume (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Q: If I've been sedentary most of my life, is starting now actually helpful?

Absolutely (Wei et al., 2024). The Wei study specifically showed that physical activity initiated in midlife provides significant dementia protection (Wei et al., 2024). You're not playing catch-up with someone who's been active their whole life—you're establishing a powerful new protective factor for your future cognitive health (Wei et al., 2024). The Hwang research similarly demonstrated that late-life activity increases are associated with lower dementia risk (Hwang et al., 2024).

Q: How much physical activity do I need?

The Wanigatunga study showed benefits at "any dose" of moderate-to-vigorous activity (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). Current guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly, but the research suggests even less provides benefit (Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025). The best amount is the amount you'll actually do consistently (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Q: Does my current health status matter?

The Wanigatunga study specifically examined this crucial question and found that benefits hold true "regardless of frailty status" (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). Even individuals with existing health conditions or reduced fitness levels can derive dementia protection from physical activity (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). This is one of the most encouraging findings from recent research, as it removes a major barrier many older adults perceive (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Q: Is any type of physical activity protective, or does it need to be aerobic?

These studies focused primarily on moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity as the measurable intervention (Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024). However, research on other forms of exercise (strength training, yoga, tai chi) also suggests cognitive benefits. Variety may be optimal, but sustained aerobic activity appears particularly protective for dementia risk reduction based on these longitudinal studies (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024).

Q: What if I have joint problems or mobility limitations?

Water-based activities like swimming and aquatic exercise, chair-based aerobics, and modified strength training can provide moderate-to-vigorous intensity without excessive joint stress (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). The key is achieving appropriate intensity, not specific exercise modality. Research shows that achieving moderate-to-vigorous intensity is what matters most for dementia prevention (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Marino et al., 2025).

Q: How soon will I see cognitive benefits?

While some studies show cognitive improvements within weeks of beginning physical activity, the dementia-protective effects demonstrated in these research studies reflect cumulative benefits over years and decades (Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025). Think of it as long-term brain insurance rather than immediate cognitive enhancement. The longitudinal nature of these studies—tracking participants over multiple decades—reveals that sustained physical activity is what provides the most robust protection (Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024).

Q: Can physical activity prevent all types of dementia?

These studies examined "all-cause dementia," meaning the protective effect applies across Alzheimer's disease and other dementia types (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Marino et al., 2025). According to Wanigatunga and colleagues, physical activity appears to provide broad protection against dementia generally (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). However, physical activity appears to be one protective factor among several, and dementia is multifactorial (Wei et al., 2024). That said, you're reducing your overall risk regardless of type (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Marino et al., 2025).

Practical Implementation: Moving Forward

Understanding the science is valuable, but actionable steps matter most. Here's how to translate this research into reality:

Start Where You Are: You don't need permission from your doctor (though you should check in if you've been very sedentary) or expensive equipment. A brisk daily walk counts. A neighborhood swimming session counts (Wei et al., 2024). Beginning physical activity consistently is what matters according to the research (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Aim for Sustainability: 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity weekly is the sweet spot supported by these studies, but you benefit from any consistent physical activity (Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025). It's better to sustain 100 minutes weekly for decades than attempt 500 minutes weekly for three months (Marino et al., 2025). The cumulative, long-term benefits are what drive dementia protection (Hwang et al., 2024).

Vary Your Activities: Combining aerobic activity with strength training and flexibility work maximizes both physical and cognitive benefits (Wei et al., 2024). Different activities engage different neural systems and provide complementary protection against cognitive decline (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

Find Social Accountability: Group fitness classes, walking groups, or exercise partners increase adherence. The social engagement itself may offer additional cognitive benefits beyond the physical activity. Research suggests that sustained, consistent physical activity requires both motivation and opportunity—social structures help with both (Marino et al., 2025).

Track Progress: Simple tracking—steps, activity duration, or workout frequency—helps maintain motivation and allows you to adjust gradually (Wei et al., 2024). Progressive improvement feels rewarding and keeps you engaged. Documentation also helps you recognize patterns in your own physical activity adherence (Hwang et al., 2024).

Address Barriers Thoughtfully: If joint pain limits exercise, water-based options exist as alternatives that still provide moderate-to-vigorous intensity (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). If time is limited, high-intensity interval training provides benefits in shorter timeframes (Marino et al., 2025). If motivation wanes, combining activity with enjoyable activities (listening to podcasts, exercising with friends) helps sustain engagement (Wei et al., 2024).

The Bigger Picture: Physical Activity as Dementia Prevention

These four studies collectively paint a powerful picture: physical activity across the adult lifespan represents one of the most accessible and evidence-supported strategies for dementia risk reduction (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024). Unlike some interventions requiring specific medications or complex procedures, physical activity is available to nearly everyone, costs little, and provides benefits far beyond cognitive health (Wei et al., 2024).

What's particularly encouraging is that the research breaks down barriers we often create. You don't need to have been active your whole life—midlife activity initiation provides robust protection (Wei et al., 2024). You don't need elite fitness—any dose of moderate-to-vigorous activity helps (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). You don't need to be in perfect health—benefits accrue regardless of frailty status (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). Starting or maintaining moderate physical activity at virtually any life stage provides meaningful protection against one of our most feared health challenges (Wei et al., 2024; Hwang et al., 2024).

The Framingham researchers showed that lifetime activity patterns matter, but also that each decade of active living contributes independently (Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024). The Health and Retirement Study confirmed that midlife activity initiation provides robust protection (Wei et al., 2024). The analysis of frailty status revealed that physical limitations don't eliminate benefits (Wanigatunga et al., 2025). These aren't contradictory findings—they're complementary pieces confirming that physical activity's brain-protective power operates through fundamental biological mechanisms that benefit nearly everyone (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024).

Conclusion: Your Brain's Best Investment

If you remember nothing else about physical activity and dementia prevention, remember this: the research is clear, consistent, and compelling (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024). Engaging in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity—whether you're 35 or 75, whether you've been active your whole life or are just starting, whether you're in peak condition or managing health challenges—provides meaningful protection against dementia and cognitive decline (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024).

The beautiful simplicity of this message shouldn't be underestimated. In an era when medical interventions are increasingly complex and expensive, one of our most powerful tools for cognitive protection is something humans have done for millennia: move our bodies (Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025).

Call to Action

Don't just read about the benefits of physical activity—experience them. This week, commit to one small action:

If you're already active, maintain your routine and celebrate your brain-protective investment (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

If you've been sedentary, start with three 20-minute brisk walks this week (Wei et al., 2024).

If you have health limitations, research one physically active option that works for your body—research shows you'll still benefit (Wanigatunga et al., 2025).

If you're in midlife, recognize that starting now puts you on a protective trajectory for your cognitive future (Wei et al., 2024).

Share this information with someone you care about. Dementia prevention is grounded in solid research and achievable for everyone (Wanigatunga et al., 2025; Wei et al., 2024; Marino et al., 2025; Hwang et al., 2024).

Your future self—with sharper memory, better focus, and greater cognitive vitality—will thank you for moving today. Because when it comes to protecting your brain, physical activity isn't just helpful. It's essential.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with qualified healthcare providers before making significant dietary changes or starting supplementation, especially if you have existing health conditions or take medications.

Related Articles

Scrambled Brain Proteins? How Diet Can Slow Age-Related Cognitive Decline | DR T S DIDWAL

References

Hwang, P. H., Lyu, C., Liu, C., Schon, K., Mez, J., & Au, R. (2024). Physical activity across the adult life course and incident dementia in the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 20(S7), e084425. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.084425

Marino, F. R., Lyu, C., Li, Y., Liu, T., Au, R., & Hwang, P. H. (2025). Physical activity over the adult life course and risk of dementia in the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA Network Open, 8(11), e2544439. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.44439

Wanigatunga, A. A., Dong, Y., Jin, M., Leroux, A., Cui, E., Zhou, X., Zhao, A., Schrack, J. A., Bandeen-Roche, K., Walston, J. D., Xue, Q. L., Lindquist, M. A., & Crainiceanu, C. M. (2025). Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity at any dose reduces all-cause dementia risk regardless of frailty status. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 26(3), 105456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2024.105456

Wei, J., Lohman, M. C., Brown, M. J., Hardin, J. W., Xu, H., Yang, C. H., Merchant, A. T., Miller, M. C., & Friedman, D. B. (2024). Physical activity initiated from midlife on risk of dementia and cognitive impairment: The Health and Retirement Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 72(12), 3668–3680. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.19109